Exclusive 3:16 Interview With Friedrich Albert Lange

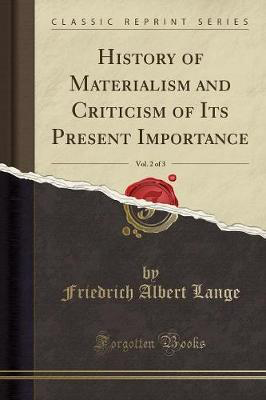

Friedrich Albert Lange is a German philosopher, pedagogist, political activist, and journalist. Lange is a significant figure among t German intellectuals concerned to think through the impact of developments in natural science for politics, philosophy, and pedagogy. Lange plays a significant role in the German labour movement and in the development of social democratic thought. He articulates a socialist Darwinism that was an alternative to early social Darwinism. His work The History of Materialism and Critique of its Contemporary Significance is a classic text in materialism and the history of philosophy well into the twentieth century. The “materialism controversy” centeres on the impact of materialist science and philosophy on religion and metaphysics. Lange’s response to the materialism controversy has influenced the neo-Kantian movement and Friedrich Nietzsche, among others. Lange is one of the originators of “physiological neo-Kantianism” and an important figure in the founding of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism. His work in logic, culminating in Logical Studies, derives the syllogistic from diagrammatic reasoning, and is admired by Ernst Schröder and John Venn.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Friederich Albert Lange: The retreat of our philosophical Romanticism in Germany ! For this reason we have every reason to plunge into the depths of the Kantian system with the most serious efforts, such as have hitherto been spent upon scarcely any other philosopher than Aristotle.

3:16: You see German philosophy as having a different trajectory from elsewhere don’t you?

FL: England, France, and the Netherlands, the true homes of modern philosophy, retired towards the end of the last century from the theatre of metaphysical war. Since Hume England has produced no great philosopher, unless we concede this rank to the acute and energetic Mill. We, like Schiller's Poet, came off empty at the partition of the world. The one practical fact that falls in this period of Idealism, the rising of the people in the liberation wars, bears indeed the character of a dreamy half-heartedness, but it betrays at the same time a mighty force that is as yet only dimly conscious of its aim.

3:16: This sounds like an early version of the analytic/continental divide.

FL: I’d put it like this: It is remarkable how our national development, more regular than that of ancient Hellas, started from the most ideal and approximated more and more to the real. At first came Poetry, whose classic age had reached its zenith in the common activity of Goethe and Schiller, when Philosophy, set going by Kant, began its stormy course. After the extinction of the Titanic efforts of Schelling and Hegel, the serious study of the positive sciences came to the front. To the old fame of Germany in philosophical criticism now succeed brilliant conquests in every branch of knowledge. Niebuhr, Ritter, and the two Humboldts may here be especially named as pioneers. Only in the exact sciences, is Germany supposed to be behind England and France and our men of science are glad to shift the blame of this upon philosophy, that has overgrown everything with its structures of fancy, and has smothered the spirit of sound inquiry.

3:16: Is Kant’s the philosophy that makes best sense of modern science?

FL: Yes. A special emphasis must here be laid on the friendly attitude of men of science, who, so far as Materialism failed to satisfy them, have inclined for the most part to a way of thinking which, in very essential points, agrees with that of Kant.

3:16: You’re careful to make clear which bits of Kant are the salient and enduringly important bits aren’t you?

FL: Indeed Richard. It is, in fact, by no means strictly orthodox Kantianism upon which we must have laid distinctive stress. The whole of the practical philosophy is the variable and perishable part of Kant's philosophy. Only its site is imperishable, not the edifice that the master has erected on this site. Even the demonstration of this site, as of a free ground for the building of ethical systems, can scarcely be numbered among the permanent elements of the system

3:16: It’s the Copernican turn that you think is of greatest significance don’t you?

FL: Yes. Kant himself was very far from comparing himself with Kepler ; but he made another comparison, that is more significant and appropriate. He compared his achievement to that of Copernicus. But this achievement consisted in this, that he reversed the previous standpoint of metaphysic. Copernicus dared, " by a paradoxical but yet true method," to seek the observed motions, not in the heavenly bodies, but in their observers.

Not less " paradoxical" must it appear to the sluggish mind of man when Kant overturns our collective experience, with all the historical and exact sciences, by the simple assumption that our notions do not regulate themselves according to things, but things according to our notions. It follows immediately from this that the objects of experience altogether are only our objects ; that the whole objective world is, in a word, not absolute objectivity, but only objectivity for man and any similarly organised beings, while behind the phenomenal world, the absolute nature of things, the ' thing-in-itself,' is veiled in impenetrable darkness.

3:16: You think Kant is the only philosophy to successfully oppose Materialism. So what makes the Kantian challenge so devastating?

FL: It’s true. All the systems that are brought to oppose Materialism, whether they are called after Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Wolff, or after our old friend Aristotle, contain precisely the same contradiction, besides, it may be, a dozen worse ones.

3:16: And this is why you actually find Materialism of seminal importance even though it ultimately fails?

FL: When we come to reckon with Materialism, everything comes to light. We here leave entirely out of view what advantages the other systems may perhaps possess in their profoundness, in their relations with art, religion, and poetry, in brilliant divinations and stimulating play of mind. Yet in the contest with Materialism, where what is wanted is proof or refutation, all the advantages of profoundness can give no help, and the hidden contradictions are brought to light.

3:16: So why do you respect Materialism then if, as you say, it’s no better than all the other failed positions and has been supplanted by your Kantianism?

FL: Materialism is the first, the lowest, but also comparatively the firmest stage in philosophy. Starting immediately from natural knowledge, it becomes a system by looking beyond the limits of this knowledge. Materialism more than any other system keeps to reality, that is, to the sum total of the necessary phenomena given to us by the compulsion of sense. But a reality such as man imagines to himself, and as he yearns after when this imagination is dispelled, an existence absolutely fixed and independent of us while it is yet known by us — such a reality does not exist and cannot exist, because the synthetic creative factor of our knowledge extends, in fact, into the very first sense-impressions and even into the elements of logic.

3:16: And that’s where your Kantianism kicks in?

FL: Yes. Kant shows that the world is not only idea, but also our idea; a product of the organisation of the species in the universal and necessary characteristics of all experience; of the individual in the synthesis that deals freely with the object. We may also say that the reality is the phenomenon for the species, while the delusive appearance, on the contrary, is a phenomenon for the individual, which only becomes an error by reality, that is, existence for the species, being ascribed to it. The task of producing harmony among phenomena and of linking the manifold that is given to us into unity belongs not merely to the synthetic factors of experience, but also to those of speculation.

Here, however, the connecting organisation of the species leaves us in the lurch: the individual speculates in his own fashion, and. the product of this speculation acquires importance for the species, or rather for the nation and contemporaries, only in so far as the individual creating it is endowed with rich and. normal talents and is typical in his modes of thought, while by his intellectual energy he is called to be a leader.

3:16: Materialism for you was important in that it helped overcome Scholasticism which for you at its heart is a confusion of the subjective and objective, something which Kant finally sorted out ?

FL: Yes. The confusion of subjective and objective elements in our conception of things is one of the most essential features of Aristotelian thought, and that this very confusion, for the most part in its clumsiest shape, became the foundation of Scholasticism. Aristotle, indeed, did not introduce this confusion into philosophy, but, on the contrary, made the first attempt to distinguish what the unscientific consciousness is always inclined to identify.

But Aristotle never got beyond extremely imperfect attempts to make this distinction; and yet precisely that element in his logic and metaphysic, which is in consequence especially perverse and immature, was regarded by the rude nations of the West as the corner-stone of their wisdom, because it best suited their undeveloped understanding. The whole era was swayed by the name, by the thought-thing, and by an utter confusion as to the meaning of sensible phenomena, which passed like dream-pictures through the miracle-loving brain of philosophizing priests.

3:16: Aristotle is sometimes talked about as helping develop a scientific approach to investigating the world but you seem to be disagreeing with that assessment?

FL: Aristotle is the creator of metaphysic, which, as everybody knows, is indebted for its unmeaning name merely to the position of these books in the series of Aristotle’s writings. The object of this science is the investigation of the principles common to all existence, and Aristotle therefore calls it the ‘ first philosophy ’ — that is, the general philosophy, which has not yet devoted itself to a special branch.

The idea of the necessity of such a philosophy was correct enough, but the solution of the problem could not even be approached until it was recognised that the universal is above all that which lies in the nature of our mind, and through which it is that we receive all knowledge. The failure to separate the subject and theobject, the phenomenon and the thing-in-itself, is here therefore especially noticeable, as, owing to this failure, the Aristotelian philosophy becomes an inexhaustible source of self-delusion.

3:16: Aristotle is usually contrasted with Plato but you think they’re both equally guilty of misunderstanding matter don’t you? Again , it’s materialism that shows their flaws?

FL: Aristotle and Plato being by far the most influential and important of the Greek philosophers whose works we possess, we are easily led to suppose a sharp antithesis between them, as though they represented two main philosophical tendencies —a priori speculation and rational empiricism. The truth is, however, that Aristotle devised a system in close dependence upon Plato, which, though not without internal inconsistencies, combines an apparent empiricism with all those errors which in the Socratico-Platonic theories radically corrupt empirical inquiry.

More conservative than Plato and Socrates, Aristotle everywhere attaches himself to tradition, to popular opinion, to the conceptions contained in language; and his ethical advances keep as near as possible to the ordinary customs and laws of Hellenic communities. He has therefore always been the favourite philosopher of conservative schools and tendencies. The unity of his theory of things Aristotle secures by the most reckless anthropomorphism.

3:16: So who were the materialists back then? Was it the Stoics?

FL: No. At the first glance we might suppose that there is no more consistent Materialism than that of the Stoics, who explain all reality to consist in bodies. But the step from absolute Monism to the physic of the Stoics is that either all bodies must be reduced to pure idea, or all spirits, including that which moves in them, must become bodies ; and even if, with the Stoics, we simply define body as that which is extended in space, the difference between these two views, utterly opposed as they seem to one another, is not really great.

3:16: Epicurus has some Materialistically sounding ideas doesn’t he?

FL: Epicurus declares that the right study of nature must not arbitrarily propose new laws, but must everywhere base itself upon actually observed facts.

3:16: And Democritus is a Materialist?

FL: Yes. A great philosopher. First, he says that out of nothing arises nothing ; nothing that is can be destroyed. All change is only combination and separation of atoms. The “boundless” of Anaximander, from which everything proceeds, the divine primitive fire of Heraclitus, into which the changing world returns, to proceed from it anew, are incarnations of persistent matter. Parmenides of Elea was the first to deny all becoming and perishing. Then he says “Nothing happens by chance, but everything through a cause and of necessity ” This proposition, already, according to a doubtful tradition, held by Leucippus, must be regarded as a decided negation of all teleology, for the “ cause” is nothing but the mathematico-mechanical law followed by the atoms in their motion through an unconditional necessity.

3:16: And this is what you take to be the sphere of all proper science don’t you?

FL: So far as physical investigation or any strict science is concerned ; for it is only from the side of efficient causes that the phenomenal world is accessible to inquiry.

3:16: What else is crucial from Democritus?

FL: He says: Nothing exists but atoms and empty space : all else is only opinion. He also said: The atoms are infinite in number, and of endless variety of form. In the eternal fall through infinite space, the greater, which fall more quickly, strike against the lesser, and lateral movements and vortices that thus arise are the commencement of the formation of worlds. Innumerable worlds are formed and perish successively and simultaneously. The soul consists of fine, smooth, round, atoms, like those of fire. These atoms are the most mobile, and by their motion, which ‘permeates the whole body, the phenomena of life are produced. Democritus therefore recognises a distinction between soul and body, which our modern Materialists would scarcely relish.

3:16: You think that Kant would have been to some extent sympathetic to Democritus’ ?

FL: Yes. For every philosophy which seriously attempts to understand the phenomenal world must come back to this point.The special case of those processes we call “ intellectual ” must be explained from the universal laws of all motion, or we have no explanation at all. The weak point of all Materialism lies just in this, that with this explanation it stops short at the very point where the highest problems of philosophy begin.

But he who devises some bungling explanation of nature, including the rational actions of mankind, starting from mere conjectural a priori notions which it is impossible for the mind to picture intelligibly to itself, destroys the whole basis of science, no matter whether he be called Aristotle or Hegel. Good old Kant would here undoubtedly in principle declare himself on the side of Democritus and against Aristotle and Zeller. He declares empiricism as thoroughly justified, so far as it does not become dogmatic, but only opposes “ temerity, and the presumption of reason mistaking its true destiny,” which “ talks largely of insightand knowledge where insight and knowledge can really do nothing,” which confounds the practical and theoretical interests, “ in order, where its convenience is interfered with, to tear away the thread of physical investigations.

It is ever the point at which a healthy philosophy cannot too sharply and energetically take Materialism into its protection. With all its elevation of the mind above the body, the ethic of Democritos is nevertheless at bottom a theory ofHedonism, standing quite in harmony with the materialistic cosmology, though far removed from the Hedonism of Epicurus, or from the system of a refined egotism which we find associated with the Materialism of the eighteenth century ; but it is nevertheless lacking in the distinctive mark of all idealistic morality, a principle of conduct taken directly from the consciousness, and asserted independently of experience.

3:16: Interestingly it wasn’t Materialism that led to scientific thinking but it was idealism wasn't it?

FL: It’s curious Richard. Not only does scarcely a single one of the great discoverers—with the solitary exception of Democritus—distinctly belong to the Materialistic school, but we find amongst the most honourable names a long series of men belonging to an utterly opposite, idealistic, formalistic, and even enthusiastic tendency.

3:16: So why then do you think Materialism important for science in the ancient and Scholastic world?

FL: The starting-point of Greek scientific activity is to be sought in Democritus and the rationalising influence of his system.

3:16: So Atomism is the key?

FL: The constant interference of gods and demons was set aside by one mighty blow, and whatever speculative natures might choose to fancy of the things that lay behind the phenomenal world, that world itself lay free from mist and exposed to view. Variously modified by men like Descartes, Newton, and Boyle, the doctrine of elementary corpuscles, and the origin of all phenomena from their movements, became the corner-stone of modern science.

3:16: Monotheism as developed in the medieval period is also important for the development of science – and also for Materialism isn’t it?

FL: The main idea of Monotheism possesses a dogmatic ductility and a speculative ambiguity which specially adapt it, amid the changing circumstances of civilisation, and in the greatest advances of scientific culture, to serve as the support of religious life. The three great Monotheistic religions have in the period of the highest intellectual development of their disciples, tended to Pantheism.

3:16: And Islam is the monotheism you see as being the most conducive to materialistic and scientific thinking?

FL: Yes. The third of the great monotheistic religions, Mohammedanism, is more favourable to Materialism. This, the youngest of them, was also the first to develop, in connection with the brilliant outburst of Arabian civilisation, a free philosophical spirit, which exercised a powerful influence primarily upon the Jews of the middle ages, and so indirectly upon the Christians of the West. Averroism prepared the way for the new Materialism. The Monotheism of Mohammed was the most absolute, and comparatively the freest from mythical adulterations.

3:16: When did philosophy take over from the theological grip on ideas and kick start modern science?

FL: Well the culminating point of Bacon’s and Descartes’ activity in establishing principles falls not much later than the great discoveries of Kepler. All these epochs of creative labour were still exercising an unslackening influence upon their contemporaries, when the materialistic physic was again systematically developed, about the middle of the seventeenth century, by Gassendi and Hobbes. We everywhere come upon intersecting threads and overlapping characteristics. Thus, Gassendi and Boyle, in the seventeenth century, take hands with the Atomism of the ancients, while Leonardi da Vinci and Luis Yives, undoubtedly men of the freshest type of the new movement, are already passed far beyond the traditions of antiquity, and attempt to found a science of experience in complete independence of Aristotle and the whole of antiquity.

3:16: You see a link between Materialism and Empiricism don’t you?

FL: Of course there’s a link. In the year 1348, at Paris, Nicolaus de Autricuria was compelled to make recantation of several doctrines, and amongst others, this doctrine, that in the processes of nature there is nothing to be found but the motion of the combination and separation of atoms. Thus Atomism and Empiricism here go hand in hand together.

3:16: So the link between Materialism and Empiricism – and Humanism too I guess - was becoming clear as early as the fourteenth century?

FL: Well, the decisive struggle fell in the fifteenth century, and of course in the year 1543 appeared, with a dedication to the Pope, the book on the “ Orbits of the Heavenly Bodies,” by Nicolaus Copernicus of Thorn. Within the last days of his life the grey-headed inquirer received the first copy of his book, and then in contentment departed from the world. “ The earth moves ” became speedily the formula by which belief in science and in the infallibility of the reason was distinguished from blind adherence to tradition.

3:16: You identify two lines of early modern forms of materialism don’t you?

FL: It is very common to carry back to Bacon and Descartes two opposing lines of philosophy, one of which stretches from Descartes through Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, and Fichte to Schelling and Hegel ; while the other runs from Bacon through Hobbes and Locke to the French Materialists of the eighteenth century.

3:16: So what do we find in the Baconian line?

FL: Bacon fixed his attention almost exclusively upon method, and expresses himself upon the most important points with equivocal reserve.‘ Spirits ’ of all kinds play a great part in the cosmology and physiology of the Neo-Platonic-Scholastic philosophy; especially, too, among the Arabians, where the spirits of the stars govern the world by means of mystical sympathies and antipathies with the spirits that inhabit earthly things. The' doctrine of ‘ spiritus ’ took scientific shape chiefly in psychology and physiology, in which its effects may be traced even to the present (for example, in the notion of the slumbering, waking, or excited ‘ animal spirits’).

We may indeed maintain that the ‘ spirits’ of this theory of nature are absolutely material, and identical with what we nowadays call forces; but even leaving out of sight that in this very notion of force there still perhaps lurks a remnant of this same want of clearness, what shall we think of a kind of matter that acts upon other material things, not by pressure and collision, but by sympathy.

3:16: And in the Cartesian line what do we find?

FL: Descartes, the progenitor of the opposite line of philosophical succession, who established the dualism between mind and material world, and took the famous ‘ Cogito ergo sum ’ as his starting-point, might at first appear opposed to the Materialistic philosophy, and that he only reacted upon it in point of its consequence and clearness. But how then shall we explain the fact that the worst of the French Materialists, De la Mettrie, wished to be a thoroughgoing Cartesian, and not without having good reasons for so wishing ?

There can be no doubt that Materialism lies only upon Bacon’s side, that the Cartesian system, if consistently carried out from his fundamental principles, must have led to an Idealism in which the whole external world appears as mere phenomenon and only the ego has any real existence. Descartes began with abstraction and deduction, and that was not only not Materialistic, but also not practical : it necessarily led him to those obvious fallacies in which, among all great philosophers, perhaps, no one abounds so much as Descartes.

But, for once, the deductive method came to the front, and in connection with it that purest form of all deduction, in which, too, as well as in philosophy, Descartes holds an honourable place - mathematics. Bacon could not endure mathematics. Although, then, in the most essential points, Materialism starts from Bacon, it was nevertheless Descartes who finally impressed upon this whole way of thinking that stamp of mechanism which appeared most strikingly in De la Mettrie’s “ L’Homme Machine”. It was really due to Descartes that all the functions as well of intellectual as of physical life were finally regarded as the products of mechanical changes.

3:16: You consider Hobbes the great Materialist from the Baconian side wasn’t he?

FL: Hobbes appears as the logical successor of Bacon. While Bacon and Descartes were still refusing it, Hobbes gave to Copernicus the place of honour that was his due. We may imagine to ourselves what would have been Hobbes’s judgment upon Hegel!

3:16: And the great seventeenth century scientists were largely in this Baconian tradition of Materialism?

FL: Two men there are in particular who represent this spirit in the generation after Hobbes—the chemist Robert Boyle, and Sir Isaac Newton. In his leaning to a clear physical and mechanical conception of the course of nature, Boyle entirely agreed with Newton; and Boyle was the older of the two, and must, in regard to the introduction into natural science of Materialistic foundations, be considered as one of the greatest of the pioneers. With him chemistry enters upon a new epoch. The breach with alchemy and with Aristotelian notions was completed by Boyle.

While these two great students of nature thus naturalized the philosophy of a Gassendi and a Hobbes in the positive sciences, and by their discoveries secured to it a definitive victory, they both, nevertheless, remained Deists in all sincerity, and without any Hobbesian reservations. Boyle’s cosmology, exactly like that of Newton, bases teleology upon the mechanism itself. The two men were so far agreed that they ascribed to God the first origination of motion among the atoms.

3:16: It was Newton that Kant revered and that his philosophy intended to capture. Gravity’s ‘spooky action at a distance’ seemed to require an unknowable mystery.

FL: Here reach one of the most important turning-points in the whole history of Materialism ; and in order to set it in its true light, we must interject a few remarks on the real service rendered by Newton. We have in our own days so accustomed ourselves to the abstract notion of forces, or rather to a notion hovering in a mystic obscurity between abstraction and concrete comprehension, that we no longer find any difficulty in making one particle of matter act upon another without immediate contact. We may, indeed, imagine that in the proposition, ‘ No force without matter,’ we have uttered something very Materialistic, while all the time we calmly allow particles of matter to act upon each other through void space without any material link.

3:16: That’s the spooky action at a distance isn’t it?

FL: Yes. From such ideas the great mathematicians and physicists of the seventeenth century were far removed. They were all in so far still genuine Materialists in the sense of ancient Materialism, that they made immediate contact a condition of influence. The collision of atoms or the attraction by hook-shaped particles, a mere modification of collision, were the type of all Mechanism and the whole movement of science tended towards Mechanism. In two important points the mathematical formula of the laws had been reached before the physical explanation—the laws of Kepler, and the law of fall, discovered by Galilei; and thus these laws troubled the whole scientific world with the question of the cause—naturally the physical, the mechanical cause—the cause to be explained from the collision of small particles—of the movement of falling and the motion of the heavenly bodies.

In particular, for a long time before and after Newton, the cause of gravitation was a favourite subject of theoretical physics. They demanded the construction, the demonstration, the mathematical formula. In the consequent working out of this demand lies Galilei’s superiority to Descartes, that of Newton and Huygens to Hobbes and Boyle, who still found satisfaction in long-spun explanations of how the thing might be possible. In consequence of this effort on the part of Newton, it now again happened, and for the third time, that the mathematical construction went ahead of the physical explanation, and on this occasion the circumstance was to attain a significance unsuspected by Newton himself.

3:16: Even Newton couldn’t believe it could he?

FL: No. The now prevailing theory of actio in distans was regarded simply as absurd ; and Newton was no exception. He repeatedly declares in the course of his great work that, for methodological reasons, he disregards the unknown physical causes of gravity, but does not doubt their existence. We see now how these views hang together, and can understand how even men like Leibniz and Johann Bernouilli were offended by the new approach.

These men are unwilling to separate mathematics from physics, and they were unable to comprehend the theory of Newton as a physical theory, a physical conception, which contradicted, and still contradicts today, the picturable principle of all physics. Newton himself, as we have seen, shared this view, but he clearly separated the mathematical construction which he could supply from the physical which he could not find, and so he became, against his will, the founder of a new cosmical theory, containing obvious inconsistency in its first elements.

The course of history has eliminated the unknown material cause, and has placed the mathematical law itself in the rank of physical causes. The collision of the atoms shifted into an idea of unity, which as such rules the world without any material mediation. What Newton held to be so great an absurdity that no philosophic thinker could light upon it, is prized by posterity as Newton’s great discovery of the harmony of the universe. Matter regulate their movements in accordance with the mathematical law without any material intervention.

3:16: So this Newtonian physics means we can’t know anything about the actual world, its essence so to speak. What we know is just what we impose on an unknowable world – is this Kantianism?

FL: Among the thinkers of ancient India, as well as among the Greeks, is found in many forms the same fundamental idea, which, in the shape given to it by Kant, is now suddenly compared to the achievement of Copernicus. Kant devotes a special eulogy to Epicurus, because in his conclusions he has never transcended the limits of experience.

3:16: But Kant didn’t want to just say that the phenomenal world is just ideas, like Protagoras and Bishop Berkeley for example ?

FL: Protagoras made himself at home in this phenomenal world. He completely gave up the idea of an absolute truth, and based his whole system on the proposition that that is true for the man which seems to him true, and that good which seems to him good. The object of Berkeley, in his contest against the phenomenal world, was to get fresh air for distressed faith, and his philosophy stops where his real aim appears.

3:16: And Kant wasn’t a skeptic, although it was Hume who woke him up to the Newtonian challenge wasn’t it?

FL: Hume is fully entitled to rank with the series of English thinkers denoted by the names of Bacon, Hobbes, and Locke ; nay, it is a question whether the first place among them all is not due to him. Hume stands on the ground prepared by Hobbes and Locke. He understands that Materialists are essentially skeptics; they no longer believe that matter, as it appears to our senses, contains the last solution of all the riddles of nature ; but they proceed in principle as if it were so, and wait until from the positive sciences themselves the necessity arises to adopt other views. Still more striking, perhaps, is Hume's kinship with Materialism in his keen polemic against the doctrine of personal identity, of the unity of consciousness, and the simplicity and immateriality of the soul.

3:16: It’s because Kant reveres both Newton and Hume that you think Kant is no crude anti-Materialist?

FL: That Hume was the man who produced so profound an impression upon Kant, whom Kant never names but with the utmost respect, must at once place Kant's relation to Materialism in a light other than that in which we are usually willing to regard it. Decided as Kant is in his opposition to Materialism, still this great mind cannot possibly be numbered with those who base their capacity for philosophy upon a measureless contempt for Materialism.

3:16: So does Kant see both Materialism and skepticism as useful for modern scientific thinking?

FL: Kant fully recognises two ways of thinking - Materialism and Skepticism — as legitimate steps towards his critical philosophy; both he regards as errors, but errors that were necessary to the development of knowledge.

3:16: So was Kant more anti-Idealism than anti-Materialism and anti-skepticism then?

FL: The ordinary Idealism, in particular, stands in the sharpest opposition to Kant's 'transcendental' Idealism. In so far as it attempts to prove that the phenomenal world does not show things to us as they are in themselves, Kant agrees with it. As soon, however, as the Idealist will teach us something as to the world of pure things, or even set this knowledge in the position of the empirical sciences, he cannot have a more irreconcilable opponent than Kant.

3:16: Are both Aristotle and Hegel are absurd to Kant?

FL: In a certain sense, indeed, to the incarnate Hegelian or Aristotelian things range themselves according to his ideas. He lives in the world of his mental cobwebs, and contrives to make everything harmonise with them.

3:16: How does Kant deal with the new situation created by Newtonian sciences then without being a skeptic, Materialist or Idealist?

FL: All judgments are, according to Kant, either analytical or synthetical. Analytical judgments assert in the predicate nothing but what was already involved in the notion of the subject. Synthetic judgments, on the contrary, increase our knowledge of the subject. We see, then, that it is the synthetic judgments by which only our knowledge is really extended, while the analytic serve as a means to make things clear and to refute errors. Judgments can be a 'priori or a posteriori. The latter draws its validity from experience, the former not. Synthetic judgments are with Kant the field of investigation.

Metaphysic pretends to extend our knowledge without needing the aid of experience. But is this possible ? Can there be any metaphysic at all ? How are, quite generally speaking, synthetic propositions a priori possible ? Skeptics and Empiricists will make common cause, and will dispose of the question with a simple No ! With dogmatic Materialism, too, all would be over, since it builds its theories upon the axiom of the intelligibility of the world, and overlooks that this axiom is at bottom only the principle of order in phenomena phenomena.

To meet them Kant brings forward a formidable ally — Mathematics. Hume conceded the pre-eminent conclusiveness of mathematics, and thought he could trace it to this, that all mathematical judgments rest only upon the principle of contradiction — in other words, that they are entirely analytical. Kant maintains, on the contrary, that all mathematical judgments are synthetical, and therefore, of course, synthetical judgments a priori, since mathematical propositions need no confirmation by experience. With Kant the real problem begins here. The problem is this : How is experience at all possible. This is not a psychological but a " transcendental " question.

3:16: Why isn’t Hume right about math, and therefore Kant’s whole system based on a fault?

FL: If he was the teachers in our national schools could then save themselves the trouble of teaching Addition. As soon as the child had acquired on its fingers or the board an intuition of 5 or of 7, and had besides learned that the number which follows 11 is called 12, it must at once be clear to him than 7 and 5 make 12, for the notions are identical! Kant is justified by the simple fact that we do not proceed in this manner.

3:16: How is it synthetic though?

FL: The one-sided Empiricists do not observe that experience is no open door through which external things, as they are, can wander in to us, but a process by which the appearance of things arises within us. The fact that we have experience at all is, however, determined by the organisation of our thinking, and this organisation exists "before experience. Kant showed first of all, in the instance of mathematics, that our thought is actually in possession of certain knowledge a priori, and that even the common understanding is never without such knowledge. Proceeding from this, he seeks to show that not only in mathematics, but in every act of knowledge, a priori elements co-operate, which throughout condition our experience.

3:16: He sets out to discover these elements doesn’t he?

FL: Yes. Kant's decisive question is - How are synthetic judgments a priori possible ? and the answer is. Because in all knowledge is contained a factor which springs not from external influences, but from the nature of the knowing subject, and which for this very reason is not accidental, like external impressions, but necessary, and is constant in all our experience.

3:16: You don’t think he gets everything right do you?

FL: His merit is that he has raised sense to the level of a source of knowledge equally valid as understanding ; his weakness, that he allowed to continue at all an understanding free from all influence of the senses. He’s wrong that mere intuition, without any cooperation of thought, affords no knowledge at all, while mere thought, without intuition, still leaves the form of thought.

However, the thought that Space and Time are forms which the human mind lends to the objects of experience is by no means such as to be rejected straight away. It is just as bold and magnificent as the hypothesis that all the phenomena of a so-called physical world, together with the space in which they are disposed, are only ideas of a purely intellectual nature. Forms of our knowledge that exist prior to experience are only through experience able to afford us knowledge, while beyond the sphere of our experience they lose all significance of any kind.

The doctrine of ' innate ideas ' is nowhere more completely refuted than here; for while, according to the old metaphysic, innate ideas are, as it were, witnesses from a supra-sensuous world, and able, indeed absolutely adapted, to be applied to supra-sensuous things, according to Kant the a prioristic elements of knowledge serve exclusively for the use of experience.

3:16: Some might argue that this just undermines science’s claims to knowing the real truth about the world?

FL: All knowledge of nature has its ultimate aim in the mechanism of atoms. Laplace teaches that a mind which should know for a given very small period of time the position and movement of all the atoms in the universe, would also necessarily be in a position to derive from these, in accordance with the laws of mechanics, the whole past and future. It could, by an appropriate treatment of its world-formula, tell us who was the Iron Mask, or how the ' President ' came to grief. There are now two places where even the mind imagined by Laplace would have to halt. We are not in a position to conceive the atoms, and we are unable, from the atoms and their motion, to explain the slightest phenomenon of consciousness.

There is no hope of ever solving this problem ; the hindrance is transcendental ! Not without justice, therefore, Du Bois- Reymond goes on to mention that all our knowledge of nature is, in truth, no knowledge at all, that it affords us merely the substitute for an explanation. We shall never forget that our whole culture rests upon this ' substitute,' which in many important respects perfectly replaces the hypothetical absolute knowledge; but it remains strictly true that the knowledge of nature, if we follow it to this point, and try to press farther on with the same principle that has brought us so far, reveals to us its own inadequacy, and sets a limit to itself.

3:16: So for Kantians like yourself our ability to know things has built in limitations? That’s why the nature of matter and consciousness are beyond us?

FL: Yes. It rests upon the fact that we can in fine conceive of nothing without any sense qualities, while, at the same time, our whole knowledge is directed towards resolving the qualities into mathematical relations. In all science we have nothing more than an "extremely difficult mechanical problem." It is impossible to see how from the co-operation of the atoms consciousness can result. Even if I were to attribute consciousness to the atoms, that would neither explain consciousness in general, nor would that in any way help us to understand the unitary consciousness of the individual.

The influence of intellectual processes upon material events is scientifically quite inconceivable. So human actions, even those of the soldiers destined to plant the cross upon the mosque of Sophia, of their generals, the diplomatists concerned, and so on — all these actions result, scientifically speaking, not from ' thoughts,' but from the atomic movements of molecular changes and so on, under the influence of the centripetal nervous activity. We must rise to the conclusion therefore that the whole activity of man, individuals as well as peoples, might go on, as it actually does' go on, without the occurring in any single individual of anything resembling a thought or a sensation. The glance of man might be just as ' full of soul/ the sound of his voice just as 'moving/ only that there would be no soul answering to this phrase, and that no one would be 'moved' in any other way than that the unconsciously changing looks would assume a gentler expression, or the mechanism of the cerebral atoms would bring a smile upon the lips or tears into the eyes.

Thus, and in no other way, did Descartes conceive the animal world.

3:16: This is Dave Chalmers ‘zombie world. So scientifically that’s all we can explain, even though we know it leaves a lot out?

FL: The two worlds are therefore to be absolutely alike, with only this difference, that in the one the whole mechanism runs down like that of an automaton, without anything being felt or thought, whilst the other is just our world. That we do not believe in the one of these worlds is nothing but the immediate effect of our peculiar personal consciousness, as each of us knows it in himself alone, and which we attribute also to everything that is externally like ourselves. Chalmers? - yes, he's worth reading. His new book on VR is basically an update on my Kantianism!

3:16: Some want to say that this shows that there’s more in the world than what science can tell us.

FL: However puzzling may seem the way in which the intellectual and the physical are connected, however inexplicable may be the nature of the latter, yet the absolute dependence of the intellectual on the physical must be asserted, so soon as it is shown, on the one hand, that the two sets of phenomena entirely correspond, and, on the other, that the physical events follow strict and immutable laws, which are merely an expression of the functions of matter. Critical Philosophy asks whether, if we had fully understood the relation of consciousness to the way in which we conceive natural objects, it would not at once be perfectly clear to us, why we must in scientific thought represent the substance of the world as matter and force? That the two problems are identical is, in fact, much more than probable. From the standpoint of the critical philosophy which bases itself on the theory of knowledge, all need disappears of breaking through the ' limits of natural knowledge ' we have been discussing, since these limits are not a foreign and hostile power, but are our own peculiar nature. We must never demand of philosophy that she should not recognise her own children in the many-coloured coat of natural science.

3:16: So science must content itself to be about knowing these things and not things-in-themselves? Aren’t we then locked in to knowing things we’ve created rather than what’s actually there?

FL: Who says that we are to occupy ourselves at all with the, to us, inconceivable ' things-in-themselves ' ? Are not the natural sciences in every case what they are, and do they not accomplish what they accomplish, quite independently of the ideas as to the ultimate grounds of all nature to which we are ourselves conducted by philosophical criticism? This is what Kant undoubtedly supposes. Space and time have reality, according to him, for the sphere of human experience, in so far as they are necessary forms of our sensible intuition; outside it they are, like all ideas that stray beyond the sphere of experience, mere delusions.

3:16: It defies common sense.

FL: Sound common sense has no right to judge here at all. Its logic of daily life is successful, although it swallows camels and never strains out gnats. The influence of universal prejudice upon its results the great public does not detect, because it is all involved in the same errors.

3:16: Given we can’t know them, how do we know that ‘things in themselves’ exist?

FL: Kant denies that the question as to the nature of things in themselves has any interest. The complaints that we do not see into the interior of things are silly and unreasonable; for such people desire that we should be able to know things and even to perceive them without senses.

3:16: So is Kant saying a dogmatic metaphysics is pointless for scientific investigations?

FL: Yes. What can these ideas do if they can exercise no influence whatever on the course of the positive sciences?

3:16: Doesn’t Kant use terms such as God and Soul to explain the unity of our experiences, which sounds like a metaphysical claim that scientific investigation doesn’t admit?

FL: The ideas Soul, World, God are only the expression of those efforts after unity that lie in our rational organisation. If we attribute to them an objective existence outside ourselves, we fall at once into the shoreless sea of metaphysical errors. So long, however, as we hold them in honour as our ideas, we only satisfy an irresistible demand of our reason. These ideas do not serve to extend our knowledge, but they do serve to refute the assertions of Materialism, and thereby to make way for the moral philosophy which Kant holds to be the most important branch of philosophy.

3:16: What do you take to be the correct position regarding freewill given your reading of Kant?

FL: Kant removes the freedom of the will, that is, he abolishes it altogether from the world that we usually call the real world — from our phenomenal world. In this latter everything is related as cause and effect and they alone can form the basis of a judgment on human actions in daily life, in medical or judicial investigations, and so on.

3:16: But what about in our everyday lives when we’re not being scientific so to speak?

FL: There we must start from the fact, that we find within ourselves a law that unconditionally prescribes to us how we ought to act.

3:16: So Kant puts everything outside of science on a law of moral duty that we’re all supposed to feel inside and that we must act upon?

FL: Yes, quite independently of all experience Kant believes that he can find in the human consciousness the moral law, which as an inner voice commands absolutely, but is, of course, not absolutely obeyed. The conception of the moral law we can only regard as an element of the mental process as matter of experience, which has to struggle with all other elements, with impulses, inclinations, habits, momentary influences, and so on. And this struggle, together with its result — the moral or immoral act — follows in its whole course the universal natural laws to which man in this respect forms no exception.

But the conception of duty which calls to us, ' Thou shalt,' cannot possibly continue clear and strong, if it is not combined with the conception of the possibility of carrying out this command. For this reason, therefore, we must, with regard to the morality of our conduct, transfer ourselves entirely into the intellectual world in which alone freedom is conceivable. He still wants, however, a bond which shall give greater certainty to the doctrine of freedom, while at the same time it binds together the practical and the theoretical philosophy.

This bond is the idea that, in order to be able to support 'practically the doctrine of freedom, we must theoretically assume it as at least possible, although we cannot know in what way it is possible.

3:16: That sounds a bit mystic. It seems to be claiming some kind of knowledge of the things in themselves, which is supposed to be unknowable.

FL: It is. This postulated possibility is built upon the notion of things in themselves as opposed to phenomena. Kant actually says that ‘Man would be a marionette or a Vaucanson's automaton put together and set agoing by a supreme master of mechanism," and the consciousness of freedom would be mere delusion, unless the actions of man were " mere determinations of man as phenomenon."

3:16: You think he gets things wrong here don’t you?

FL: This whole train of thought is wrong from the very outset. Kant wished to avoid the obvious contradiction between the Ideal and Life; but this is impossible. It is impossible because the subject, even in the moral struggle, is not noumenon but phenomenon. The corner-stone of the critical philosophy — that we do not know even our-selves as we are in ourselves, but only as we appear to ourselves — can no more be overturned by the moral will than by the will in general, after the fashion of Schopenhauer.

But even if we would suppose with Schopenhauer that the will is the thing in itself, or with Kant that in moral willing the subject is a rational thing, even this could not protect us from that contradiction ; for we have to do in every moral struggle, not with the will in itself, but with our conception of ourselves and of our will, and this conception remains unavoidably phenomenon.

3:16: So for you the difference between men and marionettes is rooted in the phenomenal world?

FL: Yes. the whole difference between an automaton and a morally acting man is undoubtedly a difference letween two phenomena. In the phenomenal world those notions of value have their root, by which we find here mere mechanicalness and there exalted earnestness.

3:16: So if you think the recourse to things in themselves is illegitimate how then do you save freewill given that science can’t deliver it?

FL: Poesy.

3:16: What?

FL: Kant would not understand, what Plato before him would not understand, that the 'intelligible world' is a world of poesy, and that precisely upon this fact rests its worth and nobleness.

3:16: Is that why you rate Schiller so highly.

FL: Schiller, with a spiritual divination, seized the core of his doctrines and purified them from scholastic dross. No thought is so calculated to reconcile poesy and science as the thought that all our 'reality ' — without any prejudice to its strict connection, undisturbed by any caprice — is only appearance. Yet this truth still remains for science, that the ' thing-in- itself ' is a mere limitative idea. Every attempt to turn its negative meaning into a positive one leads us undeniably into the sphere of poesy, and only what endures when measured by the standard of poetic purity and nobleness can claim to serve a generation as instruction in the ideal.

3:16: You think a lot of post Kantian philosophy missed the point of Kant don’t you?

FL: The man whom Schiller compared to a constructing king not only afforded nourishment to the ' dustmen ' of interpretation, but he begat also a spiritual dynasty of ambitious imitators, who, like the Pharaohs, piled one pyramid upon another into the sky, and only forgot to base them upon terra firma. We have Fichte seized upon one of the darkest points of Kant's philosophy — the doctrine of the original synthetic unity of apperception, — in order to deduce from it his creative Ego, as Schelling from the A = A, as it were from a hollow nut, conjured forth the universe and Hegel declaring Sein and Nichtsein to be identical, amid the joyful acclamations of the inquisitive youth of our universities.

3:16: Yet you think things of value came from all this mess?

FL: Well yes. If we consider only the influence of Hegel on the writing of history in his own way he has mightily contributed to the advancement of science.

3:16: Feuerbach and Compte are important to your socialism aren’t they?

FL: Feuerbach and Comte speak of three epochs of humanity. The first is the theological, the second the metaphysical, the third and last is the positive, that is, that in which man applies himself, to reality, and finds his satisfaction in the resolution of actual problems. In common with Hobbes, Comte places the aim of all science in the knowledge of the laws that regulate phenomena. Feuerbach, on the other hand, makes anthropology including physiology the universal science.

3:16: Are Comte and Feuerbach really Hegelian in spirit?

FL: Yes. In this undue prominence given to man lies a trait which is due to the Hegelian philosophy, and which separates Feuerbach from strict Materialists. The genuine Materialist will always incline to turn his gaze upon the great whole of external nature, and to regard man as a wave in the ocean of the eternal movement of matter. Kant stands alone at the sharp and perfectly clear standpoint that of things in themselves we know only one thing, precisely that one thing which Feuerbach has neglected, namely, that human knowledge shows itself as a small island in the vast ocean of all possible knowledge. Feuerbach and his followers, just because they do not observe this, are constantly falling back into transcendental Hegelianism.

3:16: Is your Kantian system idealism with materialist features?

FL: The relation of philosophy to Materialism at length attains the utmost clearness in Kant. The man who first developed the doctrine of the origin of the heavenly bodies from the mere attraction of scattered matter, who had already recognised the main features of Darwinism, and who did not hesitate to speak in his popular lectures of the development of man from an earlier animal condition as something obvious, who rejected the question of the ' seat of the soul' as irrational, and often enough let it appear that to him body and soul are the same thing, only perceived by different organs, could not possibly have had much to learn of Materialism ; for the whole philosophy of Materialism is, as it were, incorporated in the Kantian system, without changing its more idealistic character.

3:16: History is important to you isn’t it?

FL: The lack of historical apprehension interrupts the thread of progress as a whole. History and criticism are often the same thing. The depreciation of the past is accompanied by a Philistine over-estimate of the present. Through Feuerbach in Germany and Comte in France an opinion has grown up that the scientific understanding is nothing but ordinary common sense asserting its natural rights after the expulsion of hindering fantasies.

History shows us no trace of such a sudden advance of common sense upon the mere removal of some disturbing fantasy; it rather shows us everywhere new ideas making their way despite opposing prejudice so that the entire expulsion of prejudice is as a rule the final completion of the whole process, as it were the cleaning of the completed machine.

3:16: You mentioned Darwin. You’re often thought of as a socialist – not social - Darwinian. Why is Darwin so important to your philosophy and your socialism?

FL: Darwin has taken a mighty stride towards the completion of a philosophical theory of the universe which can satisfy equally the understanding and the soul, since it bases itself upon the firm foundation of facts and portrays in magnificent outlines the unity of the world without any inconsistency with details. His account of the origin of species, however, as a scientific hypothesis demands the confirmation of experiment, and Darwin will have done great service if he succeeds in calling the spirit of methodical research into a sphere which promises the richest reward, while it demands also, it is true, the utmost sacrifice and perseverance.

What renders Darwin's theory capable of such an effect upon inquiry, is not only the clear simplicity and satisfactory rounding of the fundamental idea which lay ready in the experience and methodical needs of our days, and must easily have resulted from the casual combination of the various ideas of the age. An incomparably higher merit undoubtedly lies in the persevering prosecution of an object which as early as 1837 took firm hold of the naturalist on his return from a scientific voyage, and to which he dedicated his future life.

But we must quite understand that a satisfactory verification of this great hypothesis by no means depends upon this material only, but that the independent activity of many, and, perhaps, the experimental labours of generations, are required in order to confirm the theory of natural selection by artificial selection, which may repeat in a comparatively short period the work for which nature requires thousands of years.

3:16: You see Darwin as important when we consider teleological issues, that is, whether purpose can be scientific. Surely it can’t?

FL: All teleology has its root in the view that the builder of the universe acts in such a way that man must, on the analogy of human reason, call his action purposeful. This is essentially even Aristotle's view, and even the Pantheistic doctrine of an ' immanent ' purpose holds to the idea of a purposefulness corresponding to human ideals, even though it gives up the extramundane person who in human fashion first conceives and then carries out this purpose. It can now, however, be no longer doubted that nature proceeds in a way which has no similarity with human purposefulness ; nay, that her most essential means is such that, measured by the standard of human understanding, it can only be compared with the blindest chance.

3:16: Chance based on mechanical laws presumably?

FL: Yes. What we call Chance in the development of species is, of course, no chance in the sense of the universal laws of Nature, whose mighty activity calls forth all these effects ; but it is, in the strictest sense of the word, chance, if we regard this expression in opposition to the results of a humanly calculating intelligence.

3:16: And does this cohere with your Kantianism?

FL: Yes. In the Kantian philosophy, therefore, which has sounded these questions deeper than any other, the first stage of teleology is directly identified with the principle which we have repeatedly spoken of as the axiom of the intelligibleness of the world, and Darwinism in the wider sense of the word, that is, the doctrine of a scientifically intelligible theory of descent, not only does not stand in contradiction with this teleology, but, on the contrary, is its necessary presupposition. The ' formal ' finality of the world is nothing else than its adaptation to our understanding, and this adaptation just as necessarily demands the unconditional dominion of the law of causality without mystical interferences of any kind, as, on the other hand, it presupposes the comprehensibility of things by their ordering into definite forms.

Kant, indeed, goes on to lay down a second stage of teleology, the 'objective;' and here Kant himself, as in the doctrine of free will, has not everywhere strictly drawn the line of what is critically admissible; but even this doctrine does not come into conflict with the scientific taste of natural research. On this view we regard organisms as beings in which every part is throughout determined by every other part, and we shall thus be brought, by means of the rational idea of an absolute reciprocal determination of the parts of the universe, to regard them as if they were the product of an intelligence.

3:16: You think Kant mistaken here don’t you?

FL: Yes. Kant regards this conception as indemonstrable and as demonstrating nothing, but he wrongly regards it as at the same time a necessary consequence of the organisation of our reason. For the natural sciences, however, this ' objective' teleology, too, can never be anything but a heuristic principle ; by it nothing is explained, and natural science only extends as far as the mechanical and causal explanation of things.

3:16: You see a difference in the way the English and Germans approach psychology don’t you?

FL: The distinction between the English and the German procedure in psychology may, in fact, be reduced to this: that the German scholars apply all their powers of mind to attain sure and correct principles, while the Englishmen are chiefly concerned to make out of their principles whatever can be made.

3:16: And does Kant play a role in this too?

FL: The physiology of the sense- organs is developed or corrected Kantianism, and Kant's system may, as it were, be regarded as a programme for modern discoveries in this field.

3:16: What remains of Materialism once your Kantianism is in place?

FL: The ancient Materialism, with its main belief in the sensible world, is done for; even the Materialistic conception of thought which the last century favoured cannot stand. But what may very well stand with the facts is the hypothesis that all these effects of the constellation of simple sensations rest upon mechanical conditions which, when physiology has progressed far enough, we may be able to discover. Sensation, and with it our whole intellectual existence, may still be the incessantly changing result of the co-operation of elementary activities, infinite in number and in the variety of their combinations, which may themselves be localised, somewhat as the pipes of an organ are localised, but not its melodies. The same mechanism which thus produces all our sensations produces also our idea of matter. But it has here no warranty for a special degree of objectivity.

Matter in general may just as well be merely a product of my organisation — must, in fact, be so — as colour or as any modification of colour produced by the phenomena of contrast. In Kant's days the knowledge of the dependence of our world upon our organs lay generally in the air. The Idealism of Bishop Berkeley had never been got over; but more important and influential was the Idealism of the men of science and the mathematicians. D'Alembert distinctly doubted the possibility of knowing the real objects ; Lichtenberg declares it to be impossible to refute Idealism.

To know external objects is a contradiction : it is impossible for man to go outside himself. The time when a thought could be regarded as the secretion of a special portion of the brain, or as the vibration of a particular fibre, is of course gone by. If we come to the Materialists with unconscious thinking, they may immediately conclude: If the body can without consciousness perform logical operations which we have hitherto attributed only to consciousness, then it can perform the most difficult tasks that the soul has to perform. There is then nothing to prevent us from attributing consciousness as a property to the body.

When Ueberweg says that they are images in our brain, we must not forget that our brain too is only an image, or the abstraction of an image, arising through laws which govern our ideas. It is quite in order that, in order to simplify scientific reflexion, we stop as a rule at this image ; but we must never forget that we have thus only a relation between the rest of our ideas and the idea of the brain, but no fixed point beyond this subjective sphere. There is no other way whatever of passing beyond this circle but through conjectures. The struggle between Body and Mind is ended in favour of the latter, and only thus is guaranteed the true unity of all existence.

For while it always remained an insurmountable difficulty for Materialism to explain how conscious sensation could come about from material motion, yet it is, on the other hand, by no means difficult to conceive that our whole representation of matter and its movements is the result of an organisation of purely intellectual dispositions to sensation.Accordingly, Helmholtz is entirely right when he resolves the activity of sense into a kind of inference.

3:16: You’re a socialist. What’s the link between your philosophy of science and your political philosophy?

FL: We examine a science, and we find in its doctrines only the mirror of social conditions. In place of pleasure, modern times have put Egoism ; and while the philosophical Materialists hesitated in their ethic, there was developed together with political economy a special theory of egoism, which more than any other element of modern times bears on it the stamp of Materialism. In England the doctrines of political economy developed together with the rising flood of industry and world-wide commerce into a kind of science.

Adam Smith, who found only moderate approval for his ' Theory of Morals,' won the most extensive reputation by his ' Inquiry into the Wealth of Nations.' Sympathy and Interest were with him the two great springs of human actions. From sympathy he deduced all the virtues of the individual and all the advantages of society; but after he has found Justice also by a somewhat artificial way, he makes it the true foundation of the state and of society. Inclination between the members of society, friendly regard for each other's good, are beautiful things, but they may be lacking without the state being ruined.

3:16: So is Smith’s liberal theory the source of the problem?

FL: Justice cannot be spared ; with it every community stands and falls. Smith’s ' Theory of Morals ' allows every individual in the effort after wealth and honour to exert his powers to the utmost in order to surpass his competitors, so long only as he does no injustice ; in the doctrine of the ' Wealth of Nations,' the axiom is completely asserted that every one in pursuing his own advantage at the same time furthers the good of all. But the Government has nothing further to do than to maintain all freedom for this struggle of interests. he reduced the play of interests, the marketing of Supply and Demand, to rules which even yet have not lost their importance. All the time, this market of interests was not with him the whole of life, but only an important side of it.

3:16: But Smith's followers have forgotten this haven’t they?

FL: Yes, his successors forgot the other side, and confounded the rules of the market with the rules of life; nay, even with the elementary laws of human nature. This cause indeed contributed to give to political economy a tincture of strict science, by greatly simplifying all the problems of human intercourse. Abstract political economy may help us forward, although there are in reality no beings who follow exclusively the impulse of a calculating egoism, and follow it with absolute mobility, free from any hindering emotions and influences proceeding from other qualities.

3:16: Why don’t you agree with the materialists who see people’s motivations in terms of satisfying their practical needs? Surely that’s something a socialist says?

FL: True, the English cultivators of political economy started to a large extent from thoroughly practical points of view; 'practical,' not in the old Greek sense, in which vigorous activity from moral and political motives in particular earned this honourable name but from the point of view that of a man with whom his own interests are the first thing, and who therefore supposes that it is the same with everybody else. The great interest of our times is no longer, as in antiquity, immediate enjoyment, but the accumulation of Capital.

The love of pleasure with which this age is so much reproached is, on a comparative view of the history of civilisation, not nearly so prominent as the passion for work in our industrial chiefs and the compulsion to work in the slaves of our industry. Very often, indeed, what seems to be noisy or senseless joy in frivolous amusements is nothing but a result of immoderate, galling, and brutalising labour, since the mind, by perpetual hurrying and scurrying in the service of money-making, loses the capacity for a purer, nobler, and calmly devised enjoyment. Men then involuntarily pursue their recreation with the feverish haste of acquisition, and pleasure is measured by its cost, and is hurried through as if it were a kind of duty in the days and hours set apart for it.

That such a state of things is not healthy, and can hardly exist permanently, seems obvious; but it is not less clear that in the present industrial epoch enormous achievements are accomplished, which at a future time may well serve to make the fruits of a higher culture accessible to the widest circles.

3:16: So modern pleasure is just another form of egoistic greed?

FL: What formed the shadow side to the cultured and intellectual enjoyment of Epicurus, the self-sufficient limitation to a narrow circle of friends, or even to one's own person, does not very often appear in our days even amongst wealthy egoists, and a philosophy based upon it would hardly succeed in gaining any general significance.

3:16: The world is a sad place for many people isn’t it? There’s too much poverty, too little justice?

FL: Yes, things are sad enough for the great mass of the population. If all the gigantic force of our machines and all the achievements of human hands, so infinitely perfected by the division of labour, were devoted to securing for every one what is necessary to make life tolerable and to find means and leisure for the higher development of the mind, it might perhaps even now be possible, without prejudice to the intellectual task of humanity, to diffuse the blessings of culture over all classes ; but so far this has not been the tendency of the age. In our days, of course, the exacter knowledge of the life of the people, and especially the statistics of mortality, disease, etc have refuted the old fable of the contented and healthy poor, and the always hypochondriacal and weakly rich.

We measure the value of earthly goods by the scale of the tables of mortality, and we find that even the anxieties of crowned heads are not nearly so prejudicial to health as hunger, cold, and ill-ventilated dwellings. We live, in fact, not for enjoyment, but for labour and for wants ; but amongst these wants that of pleonexia is so overbearing, that all true and lasting progress, all progress that might benefit the mass of the people, is lost, or, as it were, gained only incidentally.

3:16: You contrast this with classical cultures don’t you?

FL: The foundation-stone of classical culture is that there is a certain measure which is most wholesome in all things ; and that enjoyment depends not on the quantity of satisfied wants and the difficulty of satisfying them, but on the form in which they are produced and satisfied, much as physical beauty is determined, not by masses of material, but by the observing of certain mathematical lines.

3:16: Can we have this again?

FL: Such a revolution of views would be inconceivable without the elimination of our luxuriant pleonexia, and must, moreover, arise from a magnificent revival of the sense of community. Political economy has so far made little effort to reduce the distribution of wealth to correct principles.

3:16: That’s your socialist vision. Defenders of egoism argue that it is through their philosophy that progress is being made. What’s wrong with that perspective?

FL: Yes, it is attempted to show that the progress produced by the restless struggle of Egoism always to some extent improves the position of the most depressed strata of the population, and here is forgotten the importance of that comparison with others which plays so great a part among the rich. In face of the most crying absurdities a sort of pre-established harmony is imagined, thanks to which the most favourable result for the sum of people comes about through every man's recklessly pursuing his own interests.

However easy, too, it was to protest against the exaggerations in Mandeville's notorious ' Fable of the Bees' yet the principle that even vices contribute to the general good, was to some extent a secret article of enlightenment which, though seldom mentioned, was never forgotten, and in no department is the appearance of truth so great for such a principle as just in that of political economy. The sophisms of Helvetius in the glittering garb of rhetoric are yet easily seen through ; and every attempt to explain even the virtues of patriotism, of self-sacrifice for one's neighbour, and of bravery, from the principle of self-love, must be shattered on the fact that the natural understanding, agreeing with scientific criticism, contradicts it.

The idea that there is a special department of life for pursuing our interests, and again another for the exercise of virtue, is even yet one of the favourite ideas of superficial Liberalism.

3:16: And does this explain why the rich are so resistant to being just?

FL: Yes. Anyone who omits to pursue a debtor, if necessary, with all the rigour of the law, must either be a rich man, who may indulge himself in that sort of thing, or he incurs the severest blame. Just in the same way, too, is regarded the man who devotes his energies to the public good to the detriment of his private fortune. He who does this with special success receives, indeed, absolution and general applause, all the same whether his success is due to chance or to his own energy; but so long as this vox Dei of the mob and the fatalists has not been pronounced, the ordinary judgment maintains itself.

It condemns the poet and artist as well as the scientific inquirer and the politician; and even the religious agitator only meets with recognition if he succeeds in founding a church, or creating a great institution of which he becomes director, or if he rises to ecclesiastical dignities ; but never if, without hope of compensation, he sacrifices a position to his convictions. We are here only characterising the feelings of the great mass of the propertied classes, which, however, through their having been developed into a system of daily life, also exert their influence even upon those who personally are not without nobler impulses.

3:16: What is to be done?

FL: The questions whether dogmatic Egoism teaches the truth, and whether political economy is in the right path in the one-sided development of the doctrine of free trade, are both determined by the question whether the idea of the natural harmony of interests is a mere figment or not ; for the extreme free-trade theorists have not hesitated to base their doctrine on the supreme principle of laissez faire. But they have set up this principle not merely as a defensive maxim against misgovernment, but as the necessary consequence of the dogma that the sum of all interests is best cared for when each individual cares for himself.

3:16: You don't even think Egoism caused the great advances in justice do you?

FL: Richard, we must remark that the great advances of modern times have not, after all, been brought about by Egoism as such, but by the liberation of efforts for private ends as against the suppression of the Egoism of the majority by the stronger Egoism of the minority. It was not fatherly care which in earlier times held the place now taken by free competition, but privilege, exploitation, the antithesis of Master and Man.

3:16: So how do we work out whether selfishness can bring about justice?

FL: Well, in order to simplify the problem, first suppose a republic of individuals of equal capacities and working under the same conditions, all endeavouring with all their might to produce as much wealth as possible. It is obvious that with one part of their might they will hinder each other, while with the other part they will produce wealth for the benefit of the whole. To abolish this mutual hindrance is only conceivable in two ways : either if all acquire only for the whole, or if each single individual has his own separate sphere of acquisition without any competition. As soon as it can occur that two or more individuals strive to secure the same object, or to utilise it for purposes of production, hindrance will arise.

If you apply this abstraction to human relations we see the germ of two ideas: that of communism and that of private property. In a state of community of goods the purely egoistic tendency will be directed to the appropriation of a portion of the goods; in a pure system of private property, on the other hand, to the increasing of one's own possessions by over-reaching others.

3:16: I presume its communism that appeals to you?

FL: Well, assume that in our republic there are some goods held in common as well as goods in private ownership, and that there are certain limits to appropriation and over- reaching which are generally recognised; but in such a way that there are always legitimate means by which the individual can gain an advantage in the enjoyment of the common possessions, as well as increase his private property. The most important of these legitimate means is to consist in this, that he who renders greater services to the community receives too a greater reward. Let it suffice to point out that most men are perfectly capable, as soon as a favourable start has raised them above the necessity of gaining the necessaries of life by physical labour, of making the labour of many others tributary to themselves by speculation, by inventions, or even by the mere regular and steady direction of a business.

The fallacy of the harmony of interests is therefore, too, always connected with the special prominence of 'a principle which is an almost universal prejudice, the principle that in human life every talent and every faculty finally, though it may be through many obstacles, makes its way to a corresponding position. The exaggerated rationalistic teleology of the last century did a great deal to spread this principle.

3:16: So egoism leads to the absurdity of capitalism which discounts the vast inequalities of relative wealth it creates.