Exclusive 3:16 Interview with Friedrich Nietzsche

Interview by Richard Marshall

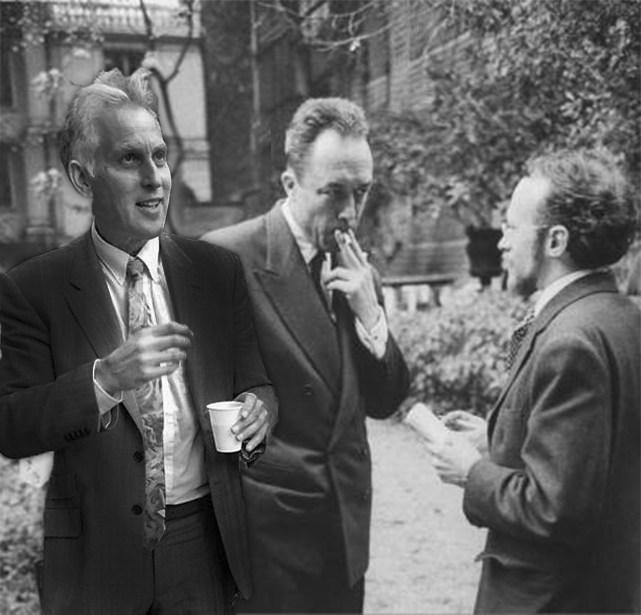

[Photos: Magister Officiorum Leonard]

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Friedrich Nietzsche: What I understand by "philosopher": a terrible explosive in the presence of which everything is in danger. So what drew me to it? The majesty of the ruling glance and condemning look, the feeling of separation from the multitude with their duties and virtues, the kindly patronage and defense of whatever is misunderstood and calumniated, be it God or devil, the delight and practice of supreme justice, the art of commanding, the amplitude of will, the lingering eye which rarely admires, rarely looks up, rarely loves.

3:16: Wow. Ok. Have you a role model?

FN: Goethe is a good example of what inspires me: Goethe — not a German event, but a European one: a magnificent attempt to overcome the eighteenth century by a return to nature, by an ascent to the naturalness of the Renaissance — a kind of self-overcoming on the part of that century. He bore its strongest instincts within himself: the sensibility, the idolatry of nature, the anti-historic, the idealistic, the unreal and revolutionary (the latter being merely a form of the unreal). He sought help from history, natural science, antiquity, and also Spinoza, but, above all, from practical activity; he surrounded himself with limited horizons; he did not retire from life but put himself into the midst of it; he was not fainthearted but took as much as possible upon himself, over himself, into himself. What he wanted was totality; he fought the mutual extraneousness of reason, senses, feeling, and will (preached with the most abhorrent scholasticism by Kant, the antipode of Goethe); he disciplined himself to wholeness, he created himself.

3:16: One of the things you are concerned with is addressing what you see as our current turning away from reality, of our tendency to dress up the world in moral ideals which you see as pure window dressing and fantasy. So you are arguing for a step back to seeing reality aren’t you? You’re a Realist? So you think some things are true, but not always good?

FN: Something might be true, even if it is also harmful and dangerous in the highest degree. In spite of all the value which may belong to the true, the positive, and the unselfish, it might be possible that a higher and more fundamental value for life generally should be assigned to pretence, to the will to delusion, to selfishness, and cupidity. It might even be possible that what constitutes the value of those good and respected things, consists precisely in their being insidiously related, knotted, and crocheted to these evil and apparently opposed things—perhaps even in being essentially identical with them.

3:16: Is this Realism where your attraction to the example of Goethe comes from?

FN: In the middle of an age with an unreal outlook, Goethe was a convinced realist: he said Yes to everything that was related to him in this respect — and he had no greater experience than that ens realissimum [most real being] called Napoleon.

3:16: And do you think to be a realist calls for a certain type of person? After all it’s something that you contend would mean standing against prevailing customs and habits of thought and behaviours wouldn’t it?

FN: Goethe conceived a human being who would be strong, highly educated, skillful in all bodily matters, self-controlled, reverent toward himself, and who might dare to afford the whole range and wealth of being natural, being strong enough for such freedom; the man of tolerance, not from weakness but from strength, because he knows how to use to his advantage even that from which the average nature would perish; the man for whom there is no longer anything that is forbidden — unless it be weakness, whether called vice or virtue.Such a spirit who has become free stands amid the cosmos with a joyous and trusting fatalism, in the faith that only the particular is loathesome, and that all is redeemed and affirmed in the whole — he does not negate anymore. Such a faith, however, is the highest of all possible faiths: I have baptized it with the name of Dionysus. One might say that in a certain sense the nineteenth century also strove for all that which Goethe as a person had striven for: universality in understanding and in welcoming, letting everything come close to oneself, an audacious realism, a reverence for everything factual. To answer your opening question, that’s what made me a philosopher.

3:16: You are very critical of our contemporary ethics aren’t you. Why?

FN: Animals and morality. — The practices demanded in polite society: careful avoidance of the ridiculous, the offensive, the presumptuous, the suppression of one’s virtues as well as of one’s strongest inclinations, self-adaptation, self-deprecation, submission to orders of rank — all this is to be found as social morality in a crude form everywhere, even in the depths of the animal world — and only at this depth do we see the purpose of all these amiable precautions: one wishes to elude one’s pursuers and be favoured in the pursuit of one’s prey.

3:16: How is this the root of the asceticism that you go on about and dislike so much?

FN: It’s rooted in the way we’re increasingly suspicious of all joy! More and more, work is becoming the only activity which has a good conscience; the inclination towards joy already calls itself 'the need to recuperate' and has begun to feel ashamed of itself. 'I owe it to my heath' - this is what we say when we are caught at a picnic. Indeed, before too long it may become impossible to yield to an inclination for the vita contemplativa (that is to say to go for a walk with one's thoughts or one's friends) at all without a feeling of self-contempt and bad conscience. Well! Formerly it was the other way around: it was work that had a bad conscience. A well-bred man concealed his work if necessity compelled him to it. The slave laboured under the apprehension that he was doing something contemptible: 'doing' itself was something contemptible. 'Only in otium and bellum is there any nobility and honour': so sounded the voice of ancient prejudice. Take even contemplative scholarship, the sort I do. Scholars now vie with active people in a sort of hurried enjoyment, so that they appear to value this mode of enjoying more than that which really pertains to them, and which, as a matter of fact, is a far greater enjoyment. Scholars are ashamed of otium. But there is one noble thing about idleness and idlers. If idleness is really the beginning of all vice, it finds itself, therefore, at least in near neighbourhood of all the virtues; the idle man is still a better man than the active. Mind you, don’t suppose that in speaking of idleness and idlers I am alluding to you. You’re far too busy busy busy.

3:16: It’s all the fault of the Christians?

FN: Well, the time is coming when we shall have to pay for having been Christians for two thousand years; we have lost the essential thing on which our lives depend; for a long while we will not know what to do with ourselves. Historically the Christians are to blame but anything which compels a person no longer to live unconditionally cuts away the roots of his power. He must wither up, that is, become dishonest. But it’s complicated: Every morality is - in contrast to laisser aller [letting go] - a part of tyranny against "nature," also against "reason": that is, however, not yet an objection to it. For to object, we would have to decree, once again on the basis of some morality or other, that all forms of tyranny and irrationality are not permitted. The strange fact, however, is that everything there is or has been on earth to do with freedom, refinement, boldness, dance, and masterly certainty, whether it is in thinking itself, or in governing, or in speaking and persuading, in arts just as much as in morals, developed only thanks to the "tyranny of such arbitrary laws," and in all seriousness, the probability is not insignificant that this is "nature" and "natural" - and not that laisser aller!

3:16: So is free will impossible?

FN: Pleeeze! Are you joking? Free will and un-free will is mythology. In the real world, it is always a matter of strong and weak wills. Here’s how it all fits together. The concept of "sin" was invented by Christianity along with the torture instrument that belongs with it, the concept of "free will," in order to confuse the instincts, to make mistrust of the instincts second nature. In the concept of the "selfless," the "self-denier," the distinctive sign of decadence, feeling attracted by what is harmful, being unable to find any longer what profits one, self-destruction is turned into the sign of value itself, into "duty," into "holiness,"into what is "divine" in man. Finally—and this is what is most terrible of all—the concept of the good man signifies that one sides with all that is weak, sick, failure, suffering of itself—all that ought to perish: the principle of selection is crossed—an ideal is fabricated from the contradiction against the proud and well-turned-out human being who says Yes, who is sure of the future, who guarantees the future—and he is now called evil. We no longer derive man from the “spirit,” from the “godhead”; we have dropped him back among the beasts. He is, in truth, anything but the crown of creation: beside him stand many other animals, all at similar stages of development.... And even when we say that we say a bit too much, for man, relatively speaking, is the most botched of all the animals and the sickliest, and he has wandered the most dangerously from his instincts—though for all that, to be sure, he remains the most interesting!

3:16: So do you think Christianity and its asceticism denies naturalism understood as a realist attitude towards nature and the world?

FN: Didn’t I just say that? Under Christianity neither morality nor religion has any point of contact with actuality. It offers purely imaginary causes ("God" "soul," "ego," "spirit," "free will" -- "unfree will" for that matter), and purely imaginary effects ("sin," "salvation," "grace," "punishment," "forgiveness of sins"). Intercourse between imaginary beings ("God," "spirits," "souls"); an imaginary natural science (anthropocentric; a total denial of the concept of natural causes); an imaginary psychology (misunderstandings of self, misinterpretations of agreeable or disagreeable general feelings -- for example, of the states of the nervus sympathicus with the help of the sign-language of religio-ethical balderdash -- , "repentance," "pangs of conscience," "temptation by the devil," "the presence of God"); an imaginary teleology (the "kingdom of God," "the last judgment," "eternal life"). -- This purely fictitious world, greatly to its disadvantage, is to be differentiated from the world of dreams; the later at least reflects reality, whereas the former falsifies it, cheapens it and denies it. Once the concept of "nature" had been opposed to the concept of "God," the word "natural" necessarily took on the meaning of "abominable" -- the whole of that fictitious world has its sources in hatred of the natural (-- the real! --), and is no more than evidence of a profound uneasiness in the presence of reality. . . . This explains everything. Who alone has any reason for lying his way out of reality? The man who suffers under it. But to suffer from reality one must be a botched reality. . . . The preponderance of pains over pleasures is the cause of this fictitious morality and religion: but such a preponderance also supplies the formula for decadence...(etc.)

3:16: It’s not just Christianity though is it. You dislike Plato too for similar reasons don’t you?

FN: Please do not throw Plato at me. I am a complete skeptic about Plato, and I have never been able to join in the customary scholarly admiration for Plato the artist. The subtlest judges of taste among the ancients themselves are here on my side. Plato, it seems to me, throws all stylistic forms together and is thus a first-rate decadent in style: his responsibility is thus comparable to that of the Cynics, who invented the satura Menippea. To be attracted to the Platonic dialogue, this horribly self-satisfied and childish kind of dialectic, one must never have read good French writers — Fontenelle, for example. Plato is boring. In the end, my mistrust of Plato goes deep: he represents such an aberration from all the basic Greek instincts, is so moralistic, so pseudo-Christian (he already takes the concept of "the good" as the highest concept) that I would prefer the harsh phrase "higher swindle" or, if it sounds better, "idealism" for the whole phenomenon of Plato. We have paid dearly for the fact that this Athenian got his schooling from the Egyptians (or from the Jews in Egypt?). In that great calamity called Christianity, Plato represents that ambiguity and fascination, called an "ideal," which made it possible for the nobler spirits of antiquity to misunderstand themselves and to set foot on the bridge leading to the Cross. And how much Plato there still is in the concept "church," in the construction, system, and practice of the church!

3:16: You oppose Thucydides to Plato don’t you?

FN: My recreation, my preference, my cure from all Platonism has always been Thucydides. Thucydides and, perhaps, Machiavelli's Il Principe are most closely related to me by the unconditional will not to delude oneself, but to see reason in reality — not in "reason," still less in "morality." For that wretched distortion of the Greeks into a cultural ideal, which the "classically educated" youth carries into life as a reward for all his classroom lessons, there is no more complete cure than Thucydides. One must follow him line by line and read no less clearly between the lines: there are few thinkers who say so much between the lines. With him the culture of the Sophists, by which I mean the culture of the realists, reaches its perfect expression — this inestimable movement amid the moralistic and idealistic swindle set loose on all sides by the Socratic schools. Greek philosophy: the decadence of the Greek instinct. Thucydides: the great sum, the last revelation of that strong, severe, hard factuality which was instinctive with the older Greeks.

In the end, it is courage in the face of reality that distinguishes a man like Thucydides from a man like Plato: Plato is a coward before reality, consequently he flees into the ideal; Thucydides has control of himself, consequently he also maintains control of things. To be honest, Christianity is Platonism for the people.

3:16: How does your idea of genealogy work in all this?

FN: Let me give you an example, the genealogy of monotheism. Start with a Moral: everything of the first rank must be causa sui. Origin in something else counts as an objection, as casting a doubt on value. All supreme values are of the first rank, all the supreme concepts – that which is, the unconditioned, the good, the true, the perfect – all that cannot have become, must therefore be causa sui. But neither can these supreme concepts be incommensurate with one another, be incompatible with one another.… Thus they acquired their stupendous concept ‘God’.… The last, thinnest, emptiest is placed as the first, as cause in itself, as ens realissimum.

3:16: So why not then agree with Rousseau and demand that we return to our pre-Christian state in nature?

FN: But Rousseau — to what did he really want to return? Rousseau, this first modern man, idealist and rabble in one person — one who needed moral "dignity" to be able to stand his own sight, sick with unbridled vanity and unbridled self-contempt. This miscarriage, couched on the threshold of modern times, also wanted a "return to nature"; to ask this once more, to what did Rousseau want to return? I still hate Rousseau in the French Revolution: it is the world-historical expression of this duality of idealist and rabble. The bloody farce which became an aspect of the Revolution, its "immorality," is of little concern to me: what I hate is its Rousseauan morality — the so-called "truths" of the Revolution through which it still works and attracts everything shallow and mediocre. The doctrine of equality! There is no more poisonous poison anywhere: for it seems to be preached by justice itself, whereas it really is the termination of justice. "Equal to the equal, unequal to the unequal" — that would be the true slogan of justice; and also its corollary: "Never make equal what is unequal." That this doctrine of equality was surrounded by such gruesome and bloody events, that has given this "modern idea" par excellence a kind of glory and fiery aura so that the Revolution as a spectacle has seduced even the noblest spirits. In the end, that is no reason for respecting it any more. I see only one man who experienced it as it must be experienced, with nausea — Goethe. And so we’re back to where we started.

3:16: If you despise equality then is democracy generally to be condemned too?

FN: Despised but tolerated. Democratic institutions are quarantine arrangements to combat that ancient pestilence, lust for tyranny: as such they are very useful and very boring.

3:16: You’re responding to the pessimism of Schopenhauer who thought that we’d be better off having never been born because pain outweighs pleasure in any life. How do your ideas engage with that? Why isn’t suicide a good response?

FN: It is always consoling to think of suicide: in that way one gets through many a bad night. But seriously, ask this? What power was it which liberated Prometheus from his vultures and transformed myth to a vehicle of Dionysian wisdom? It was the Herculean power of music. Music, which attained its highest manifestation in tragedy, had the power to interpret myth with a new significance in the most profound manner, something we have already described before as the most powerful capacity of music. I mean to say that life is brimming with beautiful things but nevertheless poor, very poor in beautiful moments and in the unveilings of those things. But perhaps that is the strongest magic of life: it is covered by a veil of beautiful possibilities, woven with threads of gold -- promising, resisting, bashful, mocking, compassionate, and seductive.

3:16: But Schopenhauer thought that nevertheless the sufferings of existence cancelled these things out didn’t he? Are you disagreeing with him?

FN: Yes. Because it’s not about suffering. There is among men as in every other animal species an excess of failures, of the sick, degenerating, infirm, who suffer necessarily; the successful cases are, among men, too, always the exception. But so what? Man can endure any how if he has a why. To judge the value of life by whether we find it now unpleasant or not — can a more wild, extravagant vanity be imagined? I guess Schopenhauer only did what philosophers are in the habit of doing—he adopted a popular prejudice and exaggerated it.

3:16: So suffering is not the problem but meaningless suffering? But then, why are you so cross with the ascetics? Don’t they give meaning to suffering?

FN: Life is hard to bear; but why act so tenderly! We are all of us fair beasts of burden, male and female asses. What do we have in common with the rosebud, which trembles because drop of dew lies on it? True, we love life, but not because we are used to living but because we are used to loving. There is always some madness in love. But there is also always some reason in madness. Of course, Judgments, value judgments concerning life, for or against, can in the last resort never be true: they possess value only as symptoms, they come into consideration only as symptoms – in themselves such judgements are stupidities. So pick one that makes life less of a slow suicide than the ascetics.

3:16: So you think you have a better answer to suffering than the meaningful suffering of the ascetics? Does education have a role in any of this?

FN: All education begins with the exact opposite of what everyone praises so highly today as ‘academic freedom.’ It begins in obedience, subordination, discipline, servitude. And just as great leaders need followers, so too must the led have a leader. A certain reciprocal predisposition prevails in the hierarchy of the spirit: yes, a kind of pre-established harmony. The eternal hierarchy that all things naturally gravitate toward is just what the so-called culture now sitting on the throne of the present aims to overturn and destroy. This ‘culture’ wants to bring leaders down to the level of its compulsory servitude, or kill them off altogether; it waylays foreordained followers searching high and low for the one who is to lead them, while its intoxications deaden even their instinct to seek. If, though, wounded and battle-weary, the two sides destined for each other find a way to come together at last, the result is a deep, thrilling bliss that resounds like the strings of an eternal lyre. And almost everything we call "higher culture" is based on the spiritualization of cruelty.

3:16: This doesn’t sound very appealing.

FN: The philosopher has to be the bad conscience of his age. As I’ve said earlier, nobody is more inferior than those who insist on being equal. He shall be the greatest who can be the most solitary, the most concealed, the most divergent, the one beyond good and evil, the master of his virtues, and of super-abundance of will.

3:16: But why do we want to extol this sort of person? Why ask for such types to exist?

FN: Well it’s not for everyone. Just a small elite. A philosophy that does not promise to make one happier and more virtuous, that rather lets it be understood that one taking service under it will probably go to ruin — that is, will be solitary in his time, will be burned and scalded, will have to know many kinds of mistrust and hate, will need to practice much hardness against himself and alas! also against others — such a philosophy offers easy flattery to no one: one must be born for it.

3:16: Wouldn’t Trump and Putin and their likes fit this picture?

FN: Are you joking? We must think of men who are cruel today as stages of earlier cultures, which have been left over; in their case, the mountain range of humanity shows openly its deeper formations, which otherwise lie hidden. They are backward men whose brains, because of various possible accidents of heredity, have not yet developed much delicacy or versatility. They show us what we all were, and frighten us. [...] In our brain, too, there must be grooves and bends which correspond to that state of mind, just as there are said to be reminders of the fish state in the form of certain human organs. But these grooves and bends are no longer the bed in which the river of our feeling courses.

3:16: So is art the value that overcomes the meaningless of suffering in a better way than asceticism? And what’s the link you make between art and polytheism as you do battle with the asceticism of monotheism.

FN: Eternal vigour of life is the important point: what matters "eternal life” or indeed life at all? The greatest advantage of polytheism. — For an individual to posit his own ideal and to derive from it his own law, joys, and rights — that may well have been considered hitherto as the most outrageous human aberration and as idolatry itself; indeed, the few who dared as much always felt the need to apologize to themselves, usually by saying: 'Not I! Not I! But a god through me.' The wonderful art and power of creating gods — polytheism — was that through which this drive could discharge itself, purify, perfect, and ennoble itself; for originally it was a base and undistinguished drive, related to stubbornness, disobedience, and envy. To be hostile to this drive to have one’s own ideal: that was formerly the law of every morality. There was only one norm: ‘the human being’— and every people believed itself to have this one and ultimate norm.

But above and outside oneself, in some distant overworld, one was permitted to behold a plurality of norms; one god was not considered the denial or anathema to another god! Here for the first time one allowed oneself individuals; here one first honored the rights of individuals. The invention of gods, heroes, and overmen (Übermenschen) of all kinds, as well as deviant or inferior forms of humanoid life, undermen, dwarfs, fairies, centaurs, satyrs, demons, and devils, was the invaluable preliminary exercise for the justification of the egoism and sovereignty of the individual: the freedom that one conceded to a god in his relation to other gods one finally gave to oneself in relation to laws, customs, and neighbors.

3:16: So as you see it the polytheist is the declaration of the multiplicity of human types, the recognition of our differences, that there isn’t just one type that fits us all. Presumably then monotheism – and its secular counterparts – denies this, hence your opposition to it?

FN: Duh! Keep up! Of course! Monotheism, in contrast, this rigid consequence of the doctrine of one normal human type — that is, the belief in one normal god beside whom there are only pseudo-gods — was perhaps the greatest danger that has yet confronted humanity. It threatened us with the premature stagnation that, as far as we can see, most other species have long reached; for all of them believe in one normal type and ideal for their species, and they have translated the morality of custom definitively into their own flesh and blood. In polytheism the free-spiritedness and many-spiritedness of humanity received preliminary form — the power to create for ourselves our own new eyes and ever again new eyes that are ever more our own — so that for humans alone among the animals there are no eternal horizons and perspectives.

3:16: So what do you make of the increasingly moralism of our societies at the moment, something that has led, in universities, to flash mobs, on line trolling, deplatforming and lack of toleration all in the name of outraged truth and justice?

FN: Everything has its day. When man gave all things a sex he thought, not that he was playing, but that he had gained a profound insight: it was only very late that he confessed to himself what an enormous error this was, and perhaps even now he has not confessed it completely. In the same way man has ascribed to all that exists a connection with morality and laid an ethical significance on the world's back. One day this will have as much value, and no more, as the belief in the masculinity or femininity of the sun has today. And all these secular priests, and popes of today, everyone with even the most modest pretentions of integrity know that they not only err but actually lie. They use morals as so many instruments of torture, systems of cruelty, whereby they become master and remains master. Is this today not the mob's? But the mob does not know what is great what is small, what is straight and honest: it is innocently crooked, it always lies.

3:16: You have some interesting and controversial things to say about the relation between the sexes. To start with can you say what your general position towards women is – some will say that you are inherently sexist.

3:16: You have some interesting and controversial things to say about the relation between the sexes. To start with can you say what your general position towards women is – some will say that you are inherently sexist.

FN: Men have hitherto treated women like birds which have strayed down to them from the heights; as something more delicate, more fragile, more savage, stranger, sweeter, soulful – but as something which has to be caged up so that it shall not fly away. On the other hand women, they want more, they learn to make claims, the tribute of respect is at last felt to be well-nigh galling; rivalry for rights, indeed actual strife itself, would be preferred: in a word, woman is losing modesty. And let us immediately add that she is also losing taste. She is unlearning to fear man: but the woman who "unlearns to fear" sacrifices her most womanly instincts. Supposing that Truth is a woman—what then? Is there not ground for suspecting that all philosophers, in so far as they have been dogmatists, have failed to understand women—that the terrible seriousness and clumsy importunity with which they have usually paid their addresses to Truth, have been unskilled and unseemly methods for winning a woman?

3:16: Your technique of suspicious hermeneutics always ends up showing how what we think is a good thing is actually screwed out of some pretty bad motivations. Can you give an example of this by sketching for us some of the deviousness involved in the kind of things extolled by the seemingly anti-sexist honesty of the 'new man'?

FN: Ok. Regarding a woman, for example, those men who are more modest consider the mere use of the body and sexual gratification a sufficient and satisfying sign of “having,” of possession. Another type, with a more suspicious and demanding thirst for possession, sees the “question mark,” the illusory quality of such “having” and wants subtler tests, above all in order to know whether the woman does not only give herself to him but also gives up for his sake what she has or would like to have: only then does she seem to him “possessed.” A third type, however, does not reach the end of his mistrust and desire for having even so: he asks himself whether the woman, when she gives up everything for him, does not possibly do this for a phantom of him. He wants to be known deep down, abysmally deep down, before he is capable of being loved at all; he dares to let himself be fathomed. He feels that his beloved is fully in his possession only when she no longer deceives herself about him, when she loves him just as much for his devilry and hidden insatiability as for his graciousness, patience, and spirituality. One type wants to possess a people—and all the higher arts of a Cagliostro and Catiline suit him to that purpose. Someone else, with a more subtle thirst for possession, says to himself: “One may not deceive where one wants to possess.” The idea that a mask of him might command the heart of the people irritates him and makes him impatient: “So I must let myself be known, and first must know myself.”

3:16: Stoicism has become appealing to many contemporary people. It's the new life app, up there with Buddhism! I guess you’re unsympathetic to this?

FN: It has gradually become clear to me what every great philosophy up till now has consisted of—namely, the confession of its originator, and a species of involuntary and unconscious auto-biography; and moreover that the moral (or immoral) purpose in every philosophy has constituted the true vital germ out of which the entire plant has always grown. So I say to the Stoics: “You desire to live "according to Nature"? Oh, you noble Stoics, what fraud of words! Imagine to yourselves a being like Nature, boundlessly extravagant, boundlessly indifferent, without purpose or consideration, without pity or justice, at once fruitful and barren and uncertain: imagine to yourselves indifference as a power—how could you live in accordance with such indifference?

To live—is not that just endeavouring to be otherwise than this Nature? Is not living valuing, preferring, being unjust, being limited, endeavouring to be different? And granted that your imperative, "living according to Nature," means actually the same as "living according to life"—how could you do differently? Why should you make a principle out of what you yourselves are, and must be? In reality, however, it is quite otherwise with you: while you pretend to read with rapture the canon of your law in Nature, you want something quite the contrary, you extraordinary stage-players and self-deluders! In your pride you wish to dictate your morals and ideals to Nature, to Nature herself, and to incorporate them therein; you insist that it shall be Nature "according to the Stoa," and would like everything to be made after your own image, as a vast, eternal glorification and generalism of Stoicism! With all your love for truth, you have forced yourselves so long, so persistently, and with such hypnotic rigidity to see Nature falsely, that is to say, Stoically, that you are no longer able to see it otherwise—and to crown all, some unfathomable superciliousness gives you the Bedlamite hope that because you are able to tyrannize over yourselves.

Stoicism is self-tyranny—Nature will also allow herself to be tyrannized over: is not the Stoic a part of Nature?... But this is an old and everlasting story: what happened in old times with the Stoics still happens today, as soon as ever a philosophy begins to believe in itself. It always creates the world in its own image; it cannot do otherwise; philosophy is this tyrannical impulse itself, the most spiritual Will to Power, the will to "creation of the world," the will to the causa prima.

3:16: What do you say about language philosophers? Are philosophers right to think that careful examination of how we speak reveals the truth about how we really think?

FN: Are you a twat? Of course not. The people on their part may think that cognition is knowing all about things, but the philosopher must say to himself: "When I analyze the process that is expressed in the sentence, 'I think,' I find a whole series of daring assertions, the argumentative proof of which would be difficult, perhaps impossible: for instance, that it is I who think, that there must necessarily be something that thinks, that thinking is an activity and operation on the part of a being who is thought of as a cause, that there is an 'ego,' and finally, that it is already determined what is to be designated by thinking—that I know what thinking is. A delusion built on an illusion of grammar. Wouldn't thinking have put over on us the biggest hoax yet? The significance of language for the evolution of culture lies in this, that mankind set up in language a separate world beside the other world, a place it took to be so firmly set that, standing upon it, it could lift the rest of the world off its hinges and make itself master of it. To the extent that man has for long ages believed in the concepts and names of things as in aeternae veritates he has appropriated to himself that pride by which he raised himself above the animal: he really thought that in language he possessed knowledge of the world. Reality is captured in the categorical nets of Language only at the expense of fatal distortion. I am afraid we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar.The various languages placed side by side show that with words it is never a question of truth, never a question of adequate expression; otherwise, there would not be so many languages. The 'thing in itself' (which is precisely what the pure truth, apart from any of its consequences, would be) is likewise something quite incomprehensible to the creator of language and something not in the least worth striving for.We cannot even reproduce our thoughts entirely in words.A philosophical mythology lies concealed in language, which breaks out again at every moment, no matter how cautious we may be. The philosopher is always caught in the nets of language.The peculiar family resemblance of all Indian, Greek and German philosophizing is explained easily enough. Precisely where linguistic kinship is present it cannot be avoided at all, thanks to the common philosophy of grammar - I mean thanks to the unconscious rule and leadership of the same grammatical functions - everything lies ready from the beginning for a similar development and sequence of philosophical systems: just as the route to certain other possibilities of interpreting the world seem almost barred.

3:16: Are philosophers and scientists really just expressing their own inner drives and incapable of impersonal, objective actions and thoughts. Doesn’t scientific enquiry become impossible in your world?

FN: Well, every impulse is imperious, and as such, attempts to philosophize. To be sure, in the case of scholars, in the case of really scientific men, it may be otherwise—"better," if you will; there there may really be such a thing as an "impulse to knowledge," some kind of small, independent clock-work, which, when well wound up, works away industriously to that end, without the rest of the scholarly impulses taking any material part therein. The actual "interests" of the scholar, therefore, are generally in quite another direction—in the family, perhaps, or in money-making, or in politics; it is, in fact, almost indifferent at what point of research his little machine is placed, and whether the hopeful young worker becomes a good philologist, a mushroom specialist, or a chemist; he is not characterised by becoming this or that. In the philosopher, on the contrary, there is absolutely nothing impersonal; and above all, his morality furnishes a decided and decisive testimony as to who he is,—that is to say, in what order the deepest impulses of his nature stand to each other. I have gradually come to understand what every great philosophy until now has been: the confession of its author and a kind of involuntarily unconscious memoir.

3:16: Can education help here?

FN: It is quite impossible for a man not to have the qualities and predilections of his parents and ancestors in his constitution, whatever appearances may suggest to the contrary. This is the problem of race. Granted that one knows something of the parents, it is admissible to draw a conclusion about the child: any kind of offensive incontinence, any kind of sordid envy, or of clumsy self-vaunting—the three things which together have constituted the genuine plebeian type in all times—such must pass over to the child, as surely as bad blood; and with the help of the best education and culture one will only succeed in deceiving with regard to such heredity.—And what else does education and culture try to do nowadays! In our very democratic, or rather, very plebeian age, “education” and “culture” must be essentially the art of deceiving—deceiving with regard to origin, with regard to the inherited plebeianism in body and soul. An educator who nowadays preached truthfulness above everything else, and called out constantly to his pupils: “Be true! Be natural! Show yourselves as you are!”—even such a virtuous and sincere ass would learn in a short time to have recourse to the furca of Horace, naturam expellere: with what results? “Plebeianism” usque recurret.

3:16: You seem to see art as the value that might press us in a better direction than the Socratic, Christianised, truth addicted moral asceticism of our current times. Can you say something about this? You claim the Truth of our lives is terrible, that life is something essentially amoral and itself is essentially a process of appropriating, injuring, overpowering the alien and the weaker, oppressing, being harsh, imposing your own form, incorporating, and at least, the very least, exploiting- though these terms don’t mean bad things to you though do they? How does aestheticism help?

FN: What I say is that it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.

3:16: How so?

FN: The equation is: Dionysus versus the crucified. Saying yes to life, even in its strangest and harshest problems; the will to life rejoicing in its own inexhaustibility...that is what I called Dionysian, that is the bridge I found to the psychology of the tragic poet. We have art in order not to die of the truth. Had we not approved of the arts and invented this type of cult of the untrue, the insight into general untruth and mendacity that is not given to us by science—the insight into delusion and error as a condition of cognitive and sensate existence—would be utterly unbearable. Honesty would lead to nausea and suicide. But now our honesty has a counterforce that helps us avoid such consequences: art, as the good will to appearance....As an aesthetic phenomenon existence is still bearable [erträglich] to us, and art furnishes us with the eye and hand and above all the good conscience to be able to make such a phenomenon of ourselves.

3:16: But doesn’t the Christian, the ascetic, live by an illusion too, and one that turns inwards in a way that invented an inner life, something not there for Homeric Greeks, for example? Hasn’t some of our greatest and richest artistic insights come from this inwardness? Surely Hamlet and the Brothers Karamazov, Beethoven and Mahler would never have come about without this internal richness your despised Christianity brought about?

FN: Well, the“supreme law of aesthetic Socratism reads roughly as follows, ‘To be beautiful everything must be intelligible,’ as the counterpart to the Socratic dictum, ‘Knowledge is virtue’”. Art, in which precisely the lie hallows itself, in which the will to deception has good conscience on its side makes Plato the greatest enemy of art that Europe has yet produced. Plato contra Homer: that is the complete, the genuine antagonism.

3:16: Yes, but because of this we have now an inner life, the sort Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Da Vinci, Mahler are all about - and isn’t that aesthetically good?

FN: So, every sufferer instinctively seeks a cause for his suffering; still more precisely, a perpetrator, still more specifically a guilty perpetrator who is receptive to suffering—in short, some living thing on which, in response to some pretext or other, he can discharge his affects in deed or in effigy: for the discharge of affect is the sufferer’s greatest attempt at relief, namely at anesthetization—his involuntarily craved narcotic against torment of any kind. It is here alone, according to my surmise, that one finds the true physiological causality of ressentiment, of revenge, and of their relatives—that is, in a longing for anesthetization of pain through affect. One wishes, by means of a more vehement emotion of any kind, to anesthetize a tormenting, secret pain that is becoming unbearable and, at least for the moment, to put it out of consciousness—for this one needs an affect, as wild an affect as possible and, for its excitation, the first best pretext.

3:16: And that leads to the invention of the rich inner life and Beethoven’s music, for example. So shouldn’t you actually find something valuable in this – not because it’s true but because the inner life makes people more interesting and aesthetically pleasing than before?

FN: To free the human soul from all its moorings for once, to immerse it in terrors, frosts, blazes, and ecstasies in such a way that it is freed from everything that is small and small-minded in listlessness, dullness, being out of sorts as if by a bolt of lightening: which paths lead to this goal? And which of them most surely?

Basically all great affects have the capacity to do so, assuming that they discharge themselves suddenly: anger, fear, lust, revenge, hope, triumph, despair, cruelty; and indeed the ascetic priest has unhesitatingly taken into his service the whole pack of wild dogs in man and unleashed first this one, then that one, always for the same purpose, to waken man out of slow sadness, to put to flight, at least for a time, his dull pain, his lingering misery, always under a religious interpretation and “justification.” Every such emotional excess exacts payment afterwards, that goes without saying—it makes the sick sicker....

3:16: But it’s interesting. This sickness getting sicker. All that inner turmoil – it’s an aesthetic turn on.

FN: The truly serious task of art is to save the eye from gazing into the horrors of night and to deliver the subject by the healing balm of illusion from the spasms of the agitations of the will. Dionysian art...wishes to convince us of the eternal joy of existence: only we are to seek this joy not in phenomena, but behind them. We are to recognize that all that comes into being must be ready for a sorrowful end; we are forced to look into the terrors of the individual existence— yet we are not to become rigid with fear: a metaphysical comfort tears us momentarily from the bustle of the changing figures. We are really for a brief moment primordial being itself, feeling its raging desire for existence and joy in existence; the struggle, the pain, the destruction of phenomena, now appear necessary to us.... We are pierced by the maddening sting of these pains just when we have become, as it were, one with the infinite primordial joy in existence, and when we anticipate, in Dionysian ecstasy, the indestructibility and eternity of this joy.

3:16: But isn’t this internalised human - a result of Chrisitianised art – and morality – aesthetically interesting and thus, on your grounds, acceptable – not because they’re true but because they invented a new kind of being. As products of your ‘slave revolt’ we’re all Hamlet’s and Raskalnikov’s now. Maybe indecisive, maybe disreputably ordinary, maybe tormented by the lies of the ascetic priests but nevertheless more interesting than Achilles because we are inward and have inner lives?

FN: Maybe. Now and then, in philosophers or artists, one finds a passionate and exaggerated worship of 'pure forms': no one should doubt that a person who so needs the surface must once have made an unfortunate grab underneath it. Perhaps these burnt children, the born artists who find their only joy in trying to falsify life's images (as if taking protracted revenge against it-), perhaps they may even belong to a hierarchy: we could tell the degree to which they are sick of life by how much they wish to see its image adulterated, diluted, transcendentalized, apotheosized- we could count the homines religiosi among the artists, as their highest class.

Men of profound sadness betray themselves when they are happy: they have a mode of seizing upon happiness as though they would choke and strangle it, out of jealousy--ah, they know only too well that it will flee from them! Solitude is a virtue for us, since it is a sublime inclination and impulse to cleanliness which shows that contact between people, “society”, inevitably makes things unclean. Somewhere, sometime, every community makes people—“base.” To live with tremendous and proud composure; always beyond - to have and not to have one's affects, one's pro and con, at will; to condescend to them, for a few hours; to seat oneself on them as on a horse, often as on an ass — for one must know how to make use of their stupidity as much as of their fire. To reserve one's three hundred foregrounds; also the dark glasses; for there are cases when nobody may look into our eyes, still less into our "grounds." And to choose for company that impish and cheerful vice, courtesy. And to remain master of one's four virtues: of courage, insight, sympathy, and solitude.

Yes. It may be that until now there has been no more potent means for beautifying man himself than piety: it can turn man into so much art, surface, play of colors, graciousness that his sight no longer makes one suffer. A man whose sense of shame has some profundity encounters his destinies and delicate decisions, too, on paths which few ever reach and of whose mere existence his closest intimates must not know: his mortal danger is concealed from their eyes, and so is his regained sureness of life. Anyone who, in intercourse with men, does not occasionally glisten in all the colors of distress, green and gray with disgust, satiety, sympathy, gloominess, and loneliness, is certainly not a man of elevated tastes; supposing, however, that he does not take all this burden and disgust upon himself voluntarily, that he persistently avoids it, and remains, as I said, quietly and proudly hidden in his citadel, one thing is certain: he was not made, he was not predestined, for knowledge. If he were, he would one day have to say to himself: ‘The devil take my good taste! but the rule is more interesting than the exception—than myself, the exception!’ And he would go down, and above all, he would go ‘inside’.

3:16: There’s something paradoxical in your position then isn’t there? You’re arguing for a kind of ‘the Opposite Person’ ,(you'd no doubt call this 'The Opposite Man') – you spend all your time showing how bad our ascetic planet is because it denies life, and then turn the thought on it’s head and say that because of that, it’s got life giving value? So the ascetic opposes what she desires and out of that comes you opposing the opposing.

FN: Yes. In all the countries of Europe, and in America, too, there now is a very narrow, imprisoned, chained type of spirits who want just about the opposite of what accords with our intentions and instincts—not to speak of the fact that regarding the new philosophers who are coming up they must assuredly be closed windows and bolted doors. They belong, briefly and sadly, among the levelers—these falsely so–called ‘free spirits’—being eloquent and prolifically scribbling slaves of the democratic taste and its ‘modern ideas’; they are all human beings without solitude, without their own solitude, clumsy good fellows whom one should not deny either courage or respectable decency—only they are unfree and ridiculously superficial, above all in their basic inclination to find in the forms of the old society as it has existed so far just about the cause of all human misery and failure—which is a way of standing truth happily upon her head!

What they would like to strive for with all their powers is the universal green–pasture happiness of the herd, with security, lack of danger, comfort, and an easier life for everyone; the two songs and doctrines which they repeat most often are ‘equality of rights’ and ‘sympathy for all that suffers’—and suffering itself they take for something that must be abolished. We opposite men, having opened our eyes and conscience to the question where and how the plant ‘man’ has so far grown most vigorously to a height—we think that this has happened every time under the opposite conditions, that to this end the dangerousness of his situation must first grown to the point of enormity, his power of invention and simulation (his ‘spirit’) had to develop under prolonged pressure and constraint into refinement and audacity, his life–will had to be enhanced into an unconditional power– will. We think that hardness, forcefulness, slavery, danger in the alley and the heart, life in hiding, stoicism, the art of experiment and devilry of every kind, that everything evil, terrible, tyrannical in man, everything in him that is kin to beasts of prey and serpents, serves the enhancement of the species ‘man’ as much as its opposite does.

3:16: Yet you find some things you actually admire about the herd?

FN: There is an involuntary falling silent, a hesitation in the eye, an end to all gestures, things which express that a soul feels close to something most worthy of reverence. The way in which reverence for the Bible in Europe has, on the whole, been maintained so far is perhaps the best piece of discipline and refinement of tradition for which Europe owes a debt of thanks to Christianity: such books of profundity and ultimate significance need for their protection an externally imposed tyranny of authority in order to last for those thousands of years which are necessary to exhaust them and sort out what they mean.

Much has been achieved when in the great mass of people (the shallow ones and all sorts of people with diarrhoea) that feeling has finally been cultivated that they are not permitted to touch everything, that there are sacred experiences before which they have to pull off their shoes and which they must keep their dirty hands off - this is almost the highest intensification of their humanity.

3:16: You find the modern spirit a problem when it lacks this reverential attitude towards some things don't you?

FN: Well, perhaps nothing makes the so-called educated people, those who have faith in "modern ideas," so nauseating as their lack of shame, the comfortable impudence in their eyes and hands, with which they touch, lick, and grope everything, and it is possible that these days among a people, one still finds in the common folk, particularly among the peasants, more relative nobility of taste and tactful reverence than among the newspaper-reading demi-monde of the spirit, among the educated.

3:16: And for the readers here at 3:16, which 5 books would you recommend that will taake us further into your philosophical world?

FN: Only five? Englishman, you could be a German. I believe only in French culture and consider everything in Europe that calls itself 'culture' a misunderstanding, not to speak of German culture.You treat culture like it was wallpaper - Without meaning, without substance, without aim: a mere 'public opinion'. You exhibit the most general deficiency in our sort of culture and education : no one learns, no one strives towards, no one teaches--enduring loneliness. Just five books? Bah! We belong to an age whose culture is in danger of perishing through the means to culture.The problem of culture is seldom grasped correctly. The goal of a culture is not the greatest possible happiness of a people, nor is it the unhindered development of all their talents; instead, culture shows itself in the correct proportion of these developments. Its aim points beyond earthly happiness: the production of great works is the aim of culture. Culture goes to the Opposite Man theme we talked about before and if we ask what we owe art I give the same answer as when we ask what Europe owes the Jews: Many things, good and bad, and above all one thing of the nature both of the best and the worst: the grand style in morality, the fearfulness and majesty of infinite demands, of infinite significations, the whole Romanticism and sublimity of moral questionableness - and consequently just the most attractive, ensnaring, and exquisite element in those iridescences and allurements to life, in the aftersheen of which the sky of our European culture, its evening sky, now glows - perhaps glows out.

I would have lied to have recommended so many - Schopenhauer, La Rochefoucauld, La Bruyère and Vauvenargues, Pascal and, most of all, Stendhal: also Philipp Mainländer's The Philosophy of Redemption, Mainländer, a new Messiah, written by Max Seiling, Paul Bourget's Essais de psychologie contemporaine, Rudolf Virchow's Die Cellularpathologie, Blanqui's L'Eternité par les astres, Karl Wilhelm von Nägeli's Mechanisch-physiologische Theorie der Abstammungslehre, Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill and David Strauss, Wilhelm Roux, Charles Baudelaire, Tolstoy's My Religion, Julius Wellhausen on Arab antiquities and his Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels, Dostoevsky's The Possessed, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Heinrich Heine. All these and more. Still, I will give you five.

Everything by Goethe. Goethe—…a grand attempt to overcome the eighteenth century through a return to nature, through a going-up to the naturalness of the Renaissance, a kind of self-overcoming on the part of that century…He did not sever himself from life, he placed himself within it…and took as much as possible upon himself, above himself, within himself. What he aspired to was totality; he strove against the separation of reason, sensibility, emotion, will…; he disciplined himself to a whole, he created himself.

Thucydedes contra Plato: Freedom means that the manly instincts which delight in war and victory dominate over other instincts, for example, over those of "pleasure." The human being who has become free — and how much more the spirit who has become free — spits on the contemptible type of well-being dreamed of by shopkeepers, Christians, cows, females, Englishmen, and other democrats. The free man is a warrior.

He said: "“There are three kinds of intelligence: one kind understands things for itself, the other appreciates what others can understand, the third understands neither for itself nor through others. This first kind is excellent, the second good, and the third kind useless.” I think he's right.

Lange introduced me to Darwin, and criticised his gradualism to boot. Lange thinks that materialism, or rather science in general, will undermine religion, or at least traditional forms of it. He takes seriously the concern that this might also undermine moral commitment. He points out that it is not obvious how effective religion really is in influencing moral behaviour. The New Testament’s claim that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven seems to have little impact on the acquisitiveness of contemporary Christian capitalists, “while the servants of the Church sit at the tables of the rich and preach submissiveness to the poor”

Holderlin wrote: 'Would I like to be a comet?/ I think so. They are swift as birds, they flower/

With fire, childlike in purity./ To desire More than this is beyond human measure.'

He's my voice. Do I still hear you, my voice? You whisper when you curse? And yet your curse should cause the bowels of this world to burst! But it continues to live and merely stares at me all the more brilliantly and coldly with its pitiless stars; it continues to live, dumb and blind as ever, and the only thing that dies is—the human being. —And yet!

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time

From the archives: