A Revisionary History of Analytic Philosophy

Interview by Richard Marshall

'Generally I think that formal logic isn’t as important to analytic philosophy as we’re taught to think it is. There’s something Whiggish about the Frege-Russell-Wittgenstein narrative as well—that philosophy got better with them and just kept on getting better afterwards.'

'For Kant, I argue, substance and attribute are problematic from an empiricist point of view because we cannot experience the necessary connexions between them either. So Kant problematised substance and attribute as Hume had problematised cause and effect before him.'

'Metaphysicians are confidently putting forward hypotheses about the nature of reality a priori once more, holding forth from their armchairs about the categories as though none of this had happened, appealing to their intuitions and what they consider to be plausible or plain common sense.'

'Quine was a naturalist who maintained that philosophy should be constrained by science. Lewis held a different view, harking back to G.E. Moore, that philosophy should be constrained by common sense too.'

'Lewis’s philosophical liberalism means that philosophers cannot expect to justify their conclusions before their co-workers any more than their poetry.'

'The lesson I take from history is that philosophy most often makes its greatest strides and most lasting contributions to human knowledge when philosophers are open to influences from beyond their immediate boundaries.'

Fraser MacBride is a philosopher working in the history of analytic philosophy, philosophy of language, philosophy of mathematics, logic and metaphysics. Here he discusses the history of analytic philosophy, the usual story that's told about its origins, his revisionary version, Kant rather than Frege as the key figure, categorical dualism vs categorical monism, Moore and Russell, Stout and Whitehead, Russell and Wittgenstein on the multiple relation theory of judgment, relations, Wittgenstein and Ramsey and Universals, analytic metaphysics now, David Lewis, Quine, Armstrong, Russell and Carnap, Armstrong and truth makers, how he sees the contemporary manifestation of the analytic tradition and philosophers and environmentalism.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Fraser MacBride: I didn’t grow up in any kind of intellectual environment; we didn’t discuss books or ideas at home whilst school life was dreary learning. But when I was 16 and studying English literature, I was given the novels of Joseph Conrad to read. It was an awakening for me. There was Conrad’s style, his precision, which still seems to me remarkable, but there was the content too. Not only his condemnation of colonialism but his reflection, to which he returns over and over, that we are liable to live out our lives at a most superficial level, that the underlying reality is something we avoid and requires courage to face. I subsequently came across Edward Said’s criticisms of Conrad and discovered that Conrad himself, despite his condemnation of colonialism, remained caught up by appearances, by his own orientalism. It was a growing sense that we rarely glimpse beyond appearance to reality, that there are always further layers to peel back before we approach reality, which led me to philosophy and, looking back I’d like to think, led to my becoming a philosopher. I wonder now what my younger self would think of the philosopher I’ve become.

3:16: You’re a philosopher who ranges over the history of philosophy – in particular analytic philosophy – philosophy of maths, philosophy of logic and science and metaphilosophy and truth, relations, universals – so there’s no way we’re going to be able to cover everything. However, your new book will help because it’s both a history of the origins of analytic philosophy and therefore focuses on several of your interest along the way. So let’s start with what you present as a pretty revisionary look at the founders of this tradition. To let us see what’s so revisionary about your version of this history, can you sketch for us the salient points of the usual way the story has been told so we can see where your history differs?

FM: Despite all the excellent scholarly work that’s been done in recent years, I still think it’s fair to say that there is an entrenched and influential story about early analytic philosophy, one typically taught to our students: Frege, Russell and Wittgenstein are the major figures, only certain familiar texts by them repay study, and it is the discovery and development of the new logic that is key to understanding the origins of analytic philosophy and its unfolding. But I argue in my book, On the Genealogy of Universals: The Metaphysical Origins of Analytic Philosophy (OUP, 2018), that other figures and other texts were important to the historical development of analytic philosophy too and it was far more metaphysics than logic that was the driver of change in the early years. The upshot is that I find the usual story exaggerated, incomplete, and mistaken in various ways. Generally I think that formal logic isn’t as important to analytic philosophy as we’re taught to think it is. There’s something Whiggish about the Frege-Russell-Wittgenstein narrative as well—that philosophy got better with them and just kept on getting better afterwards. But we need to remember that the value of our intellectual stock can go down as well as up. There are indeed plenty of respects in which analytic philosophy is more sophisticated than it was a century ago—it’s hard to deny, for example, that Tarski and Montague took our understanding of language to a new level of sophistication by applying logical and mathematical techniques hitherto unavailable. But, I argue in my book, that there are other respects, primarily metaphysical respects, in which the earlier analytic philosophers were wiser than we are.

3:16: In a way it’s not that your story doesn’t involve the usual suspects but rather that their roles have been changed. However, there is one figure who isn’t usually credited as being the grandfather of the tradition. Frege is usually given that role, but for you it’s Kant who is very significant, in particular his approach to the particular/universal distinction. So what is this distinction about and what was so important about Kant’s approach to it?

FB: Kant, following Hume, famously conceived the dual concepts of cause and effectto be problematic from an empiricist point of view because we cannot experience a cause necessitating its effects. But Kant still sought to vindicate the use of these concepts on the grounds that they belonged to a table of formal or highly general concepts or categories without which empirical judgments would be impossible. Kant’s ambitious aim in the section of the Critique of Pure Reason entitled ‘Metaphysical Deduction’ was to show that this table of concepts isn’t simply a product of association and custom but can be seen to be presupposed simply by hard reflection upon the nature of empirical judgment itself.

What’s invariably overlooked is that the concepts of substanceand attribute—particular and universal as they were later called—appear alongside cause and effect on Kant’s table of categories. For Kant, I argue, substance and attribute are problematic from an empiricist point of view because we cannot experience the necessary connexions between them either. So Kant problematised substance and attribute as Hume had problematised cause and effect before him. What’s usually pointed out is that Kant’s Metaphysical Deduction was a failure because no amount of disciplined reflection upon the nature of empirical judgement can extract the concepts on Kant’s table. But what isn’t noticed is the consequence: the concepts of substance and attribute were problematised by Kant without being vindicated by him. That was an important part of Kant’s legacy for the early analytic philosophers. Indeed it’s part of Kant’s legacy for us even though invariably overlooked.

3:16: So for you the analytic tradition starts as a dialectic about how many categories of things there are. Can you flesh out for us what this dispute is about and what ‘categorical dualism’ vs ‘categorical monism’ and ‘categorical pluralism’ are – and where the first analytics started from?

FM: Since Kant had only succeeded in problematising the categories of substance and attribute, the question was luminous for Moore and Russell: how many categories must we deploy to make sense of our experience? Categorial monism is the doctrine that there really is no need for a diversity of categories because one will do. Categorial dualism is the doctrine that exactly two are required, categorial pluralism that it is an open-ended matter how many categories are required. The early analytic philosophers were united in their opposition to ontological monism, the doctrine that only one thing exists. They favoured ontological pluralism, the doctrine that many things exist, but they differed on the number of categories they took existing things to exhibit and their views about the number of categories evolved and changed. If we focus on their thinking about categories, the broad narrative arc of early analytic philosophy involves an early revolutionary phase in which both Moore and Russell advanced categorial monism before they turned to categorial dualism. This reactionary phase was then superseded by the categorial pluralism of Whitehead, Wittgenstein and F.P. Ramsey.

3:16: How did Moore and Russell develop their thoughts in this area at the beginning?

FM: The invention of Moore and Russell’s self-consciously styled ‘New Philosophy’ can be traced back to the early summer of 1898. Moore had submitted his dissertation, The Metaphysical Basis of Ethics, for a Prize Fellowship competition at Trinity College, Cambridge. Moore and Russell were discussing a manuscript Russell was writing at the time, one he never completed, entitled An Analysis of Mathematical Reasoning Being an Inquiry into the Subject-Matter, the Fundamental Conceptions and the Necessary Postulates of Mathematics. What emerged out of their discussions was a view of the world as being maximally hospitable to the emergence of discursive thought, hospitable because the world itself—including our own minds—is conceived as consisting of pieces and blocks of information, or, as Moore and Russell described these pieces and blocks, concepts and propositions built out of concepts.

Their view was a kind of categorial monism because they admitted only one category, concepts. Moore presented his manifesto for the New Philosophy in a paper which appeared in 1899, ‘The Nature of Judgment’ which derived from the second chapter of his dissertation. Kant had espoused a categorial dualism of substance and attribute but Moore conceived of his single category of concepts as being more fundamental and so superseding the categories of substance and attribute. Meanwhile Russell argued in his Philosophy of Leibniz (1900) that because the coeval categories of substance and attribute belong to a local holism and cannot be understood separately from one another—any more than the coeval categories of cause and effect can be understood separately—we should throw out the category of attributes if the category of substance is suspect, and it is suspect because substances are scientifically redundant whilst their names are semantically inscrutable.

3:16: And what was the role of Stout and Whitehead? Was it reflection on universals/particulars that turned these guys into metaphysicians from being, respectively, a psychologist and a mathematician?

FM: Stout supervised both Moore and Russell and Whitehead supervised Russell. Through the influence they bore on them, Stout and Whitehead have a claim to being grandparents of analytic philosophy. When you come to look at things closely it’s clear that other philosophers played a role too and there isn’t a single story to be told about Moore and Russell’s influences—philosophical progress when it comes is almost always a collective achievement. Really there was a complicated pattern of agreement and disagreement between the New Philosophy and what came before. But it can’t be claimed that Frege really had an influence at the beginning because Moore and Russell’s New Philosophy was instituted some years before either of them read Frege.

Stout devoted his early career to philosophy of mind and psychology. His Manual of Psychology (1898) went through no less than five editions. But his interests turned more to metaphysics as his career progressed and he developed his own version of categorial monism. Whereas Moore and Russell had claimed there are only concepts, Stout held there are only abstract particulars (tropes as we’d now call them). It wasn’t just pure metaphysical reflection which got him there. It was a crucial epistemic consideration for Stout that abstract particulars fit the actual facts of perceptual experience, experience from whence all empirical knowledge is derived, whereas substances and attributes don’t fit at all. Whitehead began his career as a mathematician; his Treatise on Universal Algebra (1898) was his major contribution. But his work at the applied end of mathematics turned more to philosophy of science, culminating in his Concept of Nature (1920). In this work, little read now but influential and celebrated during the 20s, Whitehead espoused a version of categorial pluralism. He argued that as science advances the polymorphous character of our burgeoning experience reveals a kaleidoscopic variety of entities that cannot be adequately characterised in terms of the merely two-fold categorial scheme of particular and universal.

[Russell]

3:16: Was Russell a categorial dualist, and how did he move from a Kantian to a Fregean orientation? How does this deepen our understanding of the dispute between Russell and Wittgenstein about the multiple relation theory of judgment?

FM: The development of Russell’s metaphysics was driven by the development of his philosophy of mind. As an adherent of the New Philosophy, Russell had originally conceived of a person’s judging that p as involving her/him bearing a relation to the proposition that p, where a proposition is conceived as a self-standing piece of the world’s furniture, a single entity in its own right. By the 1910s, Russell had renounced realism about propositions—because of the mystery of their unity. Instead he conceived of a person’s judging as her/him bearing a relation to multiple entities, the entities about which the judgment is made. To make a judgment is for an agent to perform a certain kind of mental action whereby multiple entities are brought together in one mental episode. This was Russell’s ‘multiple-relation theory of judgment’.

Now Kant and Frege held different forms of categorial dualism. Kant conceived of attributes as capable of performing two roles whereas substances can only perform one. Attributes can occur predicatively, when they are ascribed to other things, or they can occur as subjects, when other attributes are ascribed to them, whereas substances cannot occur predicatively but only as subjects. Frege agreed with Kant that something which occurs as a subject cannot occur predicatively but Frege disagreed with Kant because he also held that anything that occurs predicatively cannot occur as subject. Such was Frege’s dualism of categories—Frege’s division deep in the nature of things.

Whilst Russell had advocated categorial monism early on, he had subsequently gone over to a Kantian form of categorial dualism, arguing against the Fregean form in his Principles of Mathematics (1905). But by 1918, when Russell gave his Lectures on the Philosophy of Logical Atomism, Russell had put aside the arguments of Principles and embraced a Fregean form of the dualism. So why the change of heart? Because by embracing the Fregean form, Russell was able to circumvent an objection that Wittgenstein famously made in 1913 about the multiple-relation theory of judgment.

Wittgenstein had objected that Russell’s theory places no constraints on how someone making a judgment unites multiple entities in a mental episode. So this leaves it open that someone making a judgment may cognitively stitch things together in completely nonsensical ways. Russell responded that whilst the person making a judgement bears a relation to multiple entities, the relation does not treat the entities to which it is borne miscellaneously. It treats the entities in different ways depending upon whether they’re substances or attributes—the judgment relation has bespoke slots for substances and bespoke slots for attributes so attributes are precluded from figuring in slots where substances go and substances precluded from figuring in slots where attributes go. This rules out our judging nonsense which results from permuting substances and attributes. By assigning the judgment relation this structure, Russell presupposed Fregean dualism.

It’s commonly held that Russell gave up the multiple relation theory of judgment because of Wittgenstein’s criticisms. But Russell didn’t give the theory up and he continued to put forward a version of the multiple relation theory when he delivered his Lectures on the Philosophy of Logical Atomism. He was able to do so because he had gone over to a Fregean form of categorial dualism.

[Frege]

3:16: And how does Russell’s work on the nature of judgment connect with his thinking about relations?

FM: Whilst seeking to account for the nature of judgment in terms of his multiple relation theory Russell was simultaneously striving to account for the nature of order, the deep fact about the Universe that it consists of things arranged in determinate ways. He juggled with two different theories of order. According to the first theory, relations have a direction. If the cat is on the mat this is because the above relation travels from the cat to the mat. Of course if the cat is on the mat then the mat is under the cat and this is because the converse of above, the below relation, travels in the reverse direction. According to the second theory, relations lack direction—they are, as Russell put it, ‘neutral’. So there are no converses and 'the cat is on the mat' and 'the mat is under the cat' are just two ways of saying exactly the same thing. By these lights, order is not an intrinsic feature of a state but arises from further relations which hold between the state and other things. What Russell started out writing his 1913 manuscript, The Theory of Knowledge, he held the neutral theory of relations. What he came to appreciate, before he had even finished the manuscript, was that the neutral theory is incompatible with the multiple theory of judgment. As a result of this appreciation and other difficulties that arose, Russell never completed The Theory of Knowledge. But because Russell wanted to hold onto the multiple relation of judgement theory, because he was confident he had addressed Wittgenstein’s criticisms of it from the year before, Russell gave up the neutral theory of relations and embraced the direction theory in his 1914 Harvard lectures Our Knowledge of the External World. The neutral and direction theories play an important part in the historical narrative of my book but my own view is that a version of the neutral theory wins out, which you can find out more about in my papers on relations.

3:16: You see Frank Ramsey’s paper ‘Universals’ of 1925 as the culmination of this intellectual episode – so what does Ramsey argue and why is it such an important paper for analytic philosophy? Are Ramsey and Wittgenstein on the same page here?

FM: Russell abandoned his multiple relation theory of judgment in 1919—because he no longer believed in the existence of a unified mental subject, hence did not believe in anything capable of the kind of mental act required by the multiple relation theory. In theTractatus (1919), Wittgenstein proposed to account for the possibility of judgment without presupposing a unified mental subject. His basic idea was that a proposition is an internal model, a reproduction in a mental medium of the fact that the proposition represents. A proposition is capable of modelling the fact it represents because the proposition is itself a fact, a number of psychical objects in the mental medium arranged in a determinate way, hence, being a fact, capable of sharing a form with the fact it represents. So there is no mystery about how representation is possible. Propositions are facts and being facts they are suited to represent other facts—propositions are pictures of facts whose form they share. Because this account of representation, Wittgenstein’s ‘picture theory’, operates at an extreme level of generality, only requiring a form to be shared, it leaves open what forms are shared by propositions and the facts they represent. So Wittgenstein’s account of how representation is possible leaves open what forms facts actually exhibit. Wittgenstein concluded that the forms of actual facts are only revealed to us a posteriori—it is only by analysing propositions that we employ to describe the actual phenomena that the nature of actual facts and their constituents are revealed to us. This meant Wittgenstein was a categorial pluralist because his account of the possibility of representation left open the number and nature of the categories.

Ramsey’s ‘Universals’ (1925) belongs to the period of his intellectual development when he had just returned from Vienna and was still in the thrall of the Tractatus. Ramsey embraced Wittgenstein’s ‘picture theory’ and he dwelt deeply upon Wittgenstein’s tripartite reflection that (1) language serves many purposes, (2) it is part of the human organism and no less complicated than it, hence (3) we cannot infer from the surface forms of language the forms of the propositions expressed beneath. In ‘Universals’ Ramsey argued that we cannot know a priori what the forms of fully analysed propositions, i.e.atomic propositions, are. He concluded that the task of analysis is hopeless for us, hence it is impossible for us to know the number and nature of the categories. But a year later Ramsey decided that we might discover a posteriori what the forms of the atomic propositions are. So Ramsey embraced the doctrine of categorial pluralism as Wittgenstein had before him.

Why was this an important episode for analytic philosophy? Because Ramsey had come to appreciate that the number of categories isn’t to be settled a priori as metaphysicians had traditionally supposed—that metaphysics done by metaphysicians sitting in their armchairs is an intellectual dead end. This was an important episode for analytic philosophy because Ramsey had embraced a kind of naturalism, naturalism in the sense of limiting the role of a priori philosophy in favour of reliance upon a posteriori investigation, in this case to settle the number and nature of the categories, if that matter can be settled at all. Note that this kind of naturalism needn’t require naturalism in the sense of materialism.

[Frank Ramsey]

3:16: Ok, so that helps us understand the historical landscape of the analytic tradition in its early phase – where are we now with this issue? What’s the current state of the debate – ‘has the Zeitgeist reverted to an unequivocally conservative understanding of how the categories are given – a pre-Critical or dogmatic approach to metaphysics that wouldn’t have been out of place in the 18th century?’ Are you a pluralist and is this the settled view of your contemporaries?

FM: Metaphysicians are confidently putting forward hypotheses about the nature of reality a priori once more, holding forth from their armchairs about the categories as though none of this had happened, appealing to their intuitions and what they consider to be plausible or plain common sense. Kant was dismissive of pre-critical metaphysicians that took this line. In the Prolegomena he rebuked them, “You cannot be permitted to appeal to the consent of common sense, for this is a witness whose reputation only rests on public rumour”. Nevertheless, despite the soundness of Kant’s rebuke, here we are again. I remain a categorial pluralist and a naturalist and I believe representation is a kind of modelling—for the reasons, but not only the reasons, that Russell, Whitehead, Wittgenstein and Ramsey gave us. None of this is settled. But there is no settled view amongst my contemporaries.

3:16: David Lewis is often presented as a revolutionary metaphysician in the analytic tradition – a kind of Leibnizean genius - someone who brought metaphysics back after Quine and logical positivism had seemingly outlawed it. But you think this is another narrative about analytic philosophy – and Quine and Lewis – that needs revising don’t you? So what’s the truer picture about Lewis and Quine and how does revising our views about these two give us a different picture of what the analytic tradition is?

FM: My views on Quine and Lewis have been enriched by the joint research I’ve recently done with my co-author Frederique Janssen-Lauret on Lewis’s unpublished manuscripts and correspondence, which are now housed in the Princeton Firestone Library. What we’ve found is that Lewis’s letters testify to several important respects of continuity between his philosophy and Quine’s.

D.M. Armstrong influentially held the view that Quine’s philosophy was opposed to metaphysics but that D.C. Williams kept metaphysics alive whilst Quine’s philosophy was popular. Responding to this, Lewis wrote to Armstrong, `I don't see Quine as part of a climate altogether hostile to systematic metaphysics. In fact, I see Quine as himself a systematic metaphysician ... When I took and failed my metaphysics exam as a Harvard graduate student in 1963, it was mostly Quine I'd studied in preparation. Certainly that was too narrow a plan of study. But I don't think I was studying the wrong subject altogether!' (28/10/94). Lewis went on to remark that Quine was a metaphysician with `a system in some respects allied, in some respects opposed to Williams'. We think that Lewis was exactly right about this. A better description of analytic philosophy in the 20thcentury is that metaphysics never went away and so far from starting a metaphysical revolution, Lewis carried on a tradition, albeit that he offered an original and sophisticated development of it.

3:16: Why do you say ‘… Lewis’s methodological conservatism and liberalism are severally and jointly problematic. The result is an interpretation of Lewis’s methodology that combines elements of the scientist and the poet, as Russell and Carnap described them, but not, we think, in a good way?’

FM: Of course Lewis wasn’t Quine and there are important differences as well as continuities. Quine was a naturalist who maintained that philosophy should be constrained by science. Lewis held a different view, harking back to G.E. Moore, that philosophy should be constrained by common sense too. Lewis wrote in a letter to Steve Pyke, `I am philosophically conservative: I think philosophy cannot credibly challenge either the positive convictions of common sense or the established theses of the natural sciences and mathematics' (27/7/90). But Lewis didn’t provide a method for identifying the positive convictions of common sense or interpreting what they mean when we have them or what to do when common sense convictions came into conflict with each other or when they conflict with the established theses of the natural sciences and mathematics. He left this to each philosopher to decide for themselves by exercising her or his own personal intellectual conscience in light of where he or she started out. So Lewis was also philosophically liberal. As a result of his philosophical liberalism, Lewis did not expect agreement on deep philosophical questions because philosophers exercise their intellectual consciences differently and they have different starting points. In fact Lewis expected irreconcilable differences on deep philosophical questions to be commonplace.

Russell and Carnap had lamented the lack of consensus and progress made by philosophers over the centuries. They diagnosed that philosophers had thought themselves too much akin to poets because each philosopher had sought to provide her or his own personal system as an act of self-expression. So Russell and Carnap recommended following the sciences and adopting a more communitarian method where philosophers devoted themselves to partial questions within the whole and endorsed only what they could justify before their co-workers. But Lewis’s philosophical liberalism means that philosophers cannot expect to justify their conclusions before their co-workers any more than their poetry. We develop these views and provide more evidence from Lewis’s letters in our recent papers.

[Lewis]

3:16: The nature of truth is another area that the analytic tradition has been fixated with. Why do you argue that Armstrong’s idea of an asymmetric relationship between a truth and a truthmaker isn’t actually required? Can you sketch for us what Armstrong’s truthmaker thesis was supposed to explain and why it’s not needed?

FM: Armstrong maintained that the truth of a proposition depends upon something ‘outside’ of it, how things stand in the world, but how things stand in the world doesn’t depend upon the truth of the proposition. It’s true that Epimenides lied because that’s what he did; he didn’t lie because it’s true that Epimenides lied. To explain this asymmetric dependency, Armstrong appealed to an asymmetric relation of truth-making. According to Armstrong, Epimenides’ lying, the fact that he did, made it true that he lied but not the other way around. Armstrong’s proposal raises all sorts of questions and difficulties about the character of the truth-making relation and the nature of truth-makers. But I have argued that there’s no need for us to go there because the original asymmetry can be explained without appealing to truth-makers.

To keep things simple, consider a singular representation of name-predicate form. The truth of this representation is determined by whether what the name refers to satisfies the predicate. Whether it’s true that Epimenides lied depends upon whether ‘Epimenides’ refers to someone who satisfies ‘…lied’, i.e. refers to someone who lied. By appealing to the interlocking semantic mechanisms of reference and satisfaction, I argue, we are able to explain the truth of the representation in terms of how things stand in reality. But this means that how things stand in reality can’t be explained in terms of the truth of the representation because it’s how things stand that explains the truth of the representation. To appeal to the truth of a representation to explain the things it refers to being as it describes, takes us around in an explanatory circle and the need to avoid such circularity already suffices to explain the felt asymmetry but without needing to appeal to truth-makers.

3:16: As a take home, can you say something about the analytic tradition as a whole and as you see it now. It’s often maligned as being scientistic, positivist, overly technical, boring, trivial, empty and narrow in its field of interest but you’d dispute this wouldn’t you – analytic philosophy approaches more or less anything you care to mention these days doesn’t it – so what distinguishes it from other traditions and why do you self identify (if you do) as being part of it?

FM: When you start looking closely at the conditions which made possible the emergence of early analytic philosophy in Cambridge in the late 1890s, you find great variety and a host of influences at work—from engagement with the great dead philosophers, other philosophical schools in England, Scotland and further afield from the continent, and other disciplines as well, including mathematics, the natural sciences and classics. Early analytic philosophy was an interdisciplinary and Pan-European achievement. I think that Russell and Moore’s intellectual stature didn’t consist solely in their intrinsic brilliance, although they had that too, but in their capacity to channel these forces even for a while. And we can say something similar about the Polish School and the Vienna Circle which succeeded Moore and Russell at the forefront of developments in analytic philosophy.

The lesson I take from history is that philosophy most often makes its greatest strides and most lasting contributions to human knowledge when philosophers are open to influences from beyond their immediate boundaries. Saying this doesn’t commit me to scientism because it doesn’t require the natural sciences to have some privileged epistemic or normative status any more than the social sciences, arts or humanities which we ignore at our peril.

3:16: You're concerned about global warming and the environment and have been recently campaigning to get philosophers to do something about the way they work to address these concerns. Can you tell us what you're suggesting they do?

FM: I’ve been campaigning for philosophy departments in UK universities to reduce their carbon footprints by flying less for work and using more video-conferencing instead. The British Philosophical Association has adopted the policy and so far 20 departments and 6 learned societies have signed up. The point of the policy isn’t just for philosophers to churn less carbon into the atmosphere but by putting our best foot forward to encourage our institutions and wider society to come along with us. My hope is that philosophers will turn their energy and ingenuity towards finding ways to be part of the solution to the climate emergency rather than being part of the problem. So I’m suggesting that philosophers working in the UK who are concerned about the climate emergency encourage their departments to sign up, that philosophers outside the UK encourage their institutions to adopt a similar policy and that anyone who isn’t in a position of institutional influence should drive less, fly less and avoid meat because they’ll find that the people around them will notice what they’re doing and others will follow suit. And all of us, I’m suggesting, including staff and students, should join campaigns for their institutions to divest from fossil fuels.

3:16: And finally, are there five books you could recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

FM: That’s such a difficult question, because I’ve found that to make progress in one area of philosophy it’s so often required to pay attention to another, including the history of the subject. So I’ve negotiated my way through a lot of territory to arrive where I am now. But here are five books that were important to me when I was starting out and I still feel their influence.

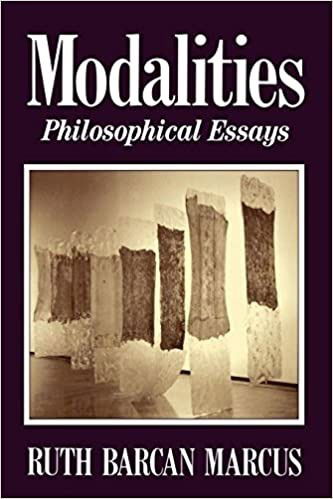

Ruth Barcan Marcus, Modalities, Oxford University Press, 1993

George Boolos, Logic, Logic and Logic, Harvard University Press, 1998

P.F. Strawson, Individuals, Methuen, 1959

W.V. Quine, Word & Object, MIT Press, 1960

D.M. Armstrong, Universals & Scientific Realism, Vol. I

and II, Cambridge University Press, 1978

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes