Anti-Theory Philosophy

Interview by Richard Marshall.

'Philosophy is not an empirical subject and does not address empirical questions (or at least, when it does, it makes a mistake). It also is not a purely formal subject, in that it does not involve exclusively and explicitly rule-governed reasoning from a set of axioms to some number of derived statements or theorems. Intuitions, speculations, common sense, and ordinary language play a significant role and rightly so.'

'I do think that we are witnessing a substantial illiberalism in the West today and that it is ultimately a non-partisan development, insofar as we see it on both the Left and the Right. Incidentally, I think that “Left” and “Right” are increasingly meaningless in today’s politics, as we are in the midst of a substantial realignment...'

'Once in the fray, I became more interested in the subject, both intellectually and as a matter of social policy, and convinced that gender-identity theory and activism was not only a serious social threat – I defy anyone to look plainly at what is going on with the “transitioning” of young children and adolescents and come away thinking that it’s anything but a disaster – but that it is going to destroy the civil rights coalition, which it is in the process of doing, with lesbians feeling increasingly alienated from the coalition and traditional feminists (calling them “radical feminists” is just stupid, insofar as their feminism is no more radical than that of Marlo Thomas’s 1972 made-for-children album/film, Free to Be You and Me) being thrown out of it entirely and lumped together with Trumpers and other assorted right-wing troglodytes.'

'At another level, I really dislike moralizing and preaching, as they inevitably lead to ugly hypocrisies, insofar as the moralizers and preachers are human. So, when it turned out that Singer, who has written on behalf of active euthanasia for people who are at the end of the proverbial road, spent thousands upon thousands of dollars on his mother’s Alzheimer’s care, the right conclusion for him to have drawn would have been that his philosophy must have gone off the rails somewhere, but instead, he chose to hide behind weakness of will, which strikes me as dishonest and weasely.'

'The brief period of anti-theory – the “interruption” – was the result of several forces coming together: (a) cumulative intellectual exhaustion, as one definition of ‘art’ after another was rendered anachronistic by art history; (b) specific art historical developments, such as the Readymades, which seemed definition-defying; (c) the realization in the philosophy of language, largely fueled by the later Wittgenstein, that many, if not most terms do not admit of explicit definition or even of analysis in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.'

Daniel A Kaufman is currently Professor of Philosophy at Missouri State University. He also edits and publishes an online magazine devoted to the intersection of philosophy, the humanities and social sciences, and popular culture, "The Electric Agora." Here he discusses whether philosophy is a humanities subject, the relationship between philosophy and wisdom, whether philosophy is increasingly philistine, public philosophy, the attack on liberalism, whether philosophy is racist and sexist, the feminist/trans issue, what's wrong with Peter Singer's utilitarianism, philosophy of art and the New Wave, being an anti-theorist in philosophy of art and what philosophical positions he defends.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Daniel A Kaufman: I was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan from 1986-1990 and originally double-majored in political science and history, with the idea of going to law school. At some point, I soured on political science, and dropped the major. I already had taken an Introduction to Philosophy class, as part of a general education requirement, and really enjoyed it, so I added a philosophy major to my history major.

I don’t recall exactly when I dropped the idea of going to law school, but the idea of becoming a professor arose out of my love of the university experience. I realized at some point in the second half of my undergraduate career that I liked the university environment more than any other and that I wanted to become a professor. I could have gone either way – philosophy or history – but philosophy more suited my temperament, which inclines towards discussion, debate, and more freewheeling thought, across myriad subject matter.

3:AM: You’re interested, amongst other things, with the intersection of philosophy with the humanities and the social sciences. So would you say philosophy is a humanities subject or not really? I ask because so many departments in the Anglo/American university sector seem to focus heavily on aspects of philosophy that seem much closer in interest with the natural and applied sciences, logic and maths?

3:16: I do believe that philosophy belongs firmly within the humanities, but I don’t think this precludes technical work in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of language and linguistics, etc. Indeed, I was trained primarily in the philosophy of language and linguistics in the very analytic graduate program in philosophy at the CUNY Graduate center during the 1990’s.

Philosophy is not an empirical subject and does not address empirical questions (or at least, when it does, it makes a mistake). It also is not a purely formal subject, in that it does not involve exclusively and explicitly rule-governed reasoning from a set of axioms to some number of derived statements or theorems. Intuitions, speculations, common sense, and ordinary language play a significant role and rightly so.

The technical apparatus of logic and formal linguistics provide a powerful set of tools with which to address any number of important problems, but they do not exhaust the philosophical toolbox, and there are many problems for which they are not particularly well-suited for getting at what is at issue.

My problem with philosophy today isn’t so much that it’s subject-matter is determined by questions in science and mathematics to too great of a degree, though one might argue that this is somewhat the case, but that it has adopted too constricted a set of tools. As I argued in a recent piece I did for Philosophy Now, philosophy historically has had a significant literary dimension, and there is very little of that in the professional academic publishing in philosophy today. I think that both philosophical fiction and the philosophical essay should be included in the professional, academic “research” that professors may do in order to earn tenure and promotion. My view, then, is not that technical philosophers should cease what they are doing, but rather, that scholarly work, in the analytic tradition, should include other types of work as well.

3:16: Additionally, how do you see the relationship between philosophy and wisdom? Philosophy these days doesn’t seem to be very interested in wisdom and seems much more interested in knowledge?

DK: I published a paper on this, back in 2006, entitled “Knowledge, Wisdom, and the Philosopher.” I did quite a bit of historical work there, in order to establish that one might view the history of Western philosophy as consisting of (1) a mainline tradition that is essentially (small ‘r’) rationalistic and for which knowledge is the primary aim of philosophical enquiry and (2) a significant philosophical counterculture that is anti-rationalist and for which wisdom is the discipline’s primary aim.

I also argue in the essay that wisdom is inherently conservative, and I think that beyond professional philosophy’s rationalistic approach, the revolutionary/liberatory political orientation among the majority of philosophers today explains to a good degree the lack of interest in wisdom that we see displayed in contemporary philosophy. Wisdom, after all, must take seriously tradition, custom, habit – what Burke called “prejudice” – common understanding and common linguistic usage, but contemporary philosophers, especially when working in social, political, and applied-ethical areas tend to be inclined in the opposite direction: towards subverting; overturning; redefining by fiat; etc.

3:16: Is this situation – both the idea that science dominates and wisdom is marginal - a matter of philosophy becoming too parochial, philistine and ahistorical in its orientations?

DK: I think that historically, parochialism and philistinism in philosophy have been effects that then became causes. They are the products of excessive (small ‘r’) rationalism and the division of intellectual labor that first emerged out of the Scientific Revolution of the 17thcentury, but which became deforming with the disciplinization and professionalization of the subject in the 20thcentury, as a result of which (analytic) philosophy increasingly sought to adopt the disciplinary posture of the sciences. They also can be the result of a sort of “morality everywhere” attitude that is a common implication of some of the most widely embraced moral philosophies and about which we might talk more later.

I did an essay on the subject of philistinism and philosophy in which I expand upon some of these ideas. Also a dialogue over at BloggingHeads.

3:16: You’re an editor of the online philosophical magazine ‘The Electric Agora’ – can you tell us something about what got you involved in this project and how important do you think it is that the ideas of philosophers in the academy get aired outside with a broader public?

DK: The creation of The Electric Agora was serendipitous. I had developed a relationship with Massimo Pigliucci as a regular commenter on his old blog, Scientia Salon; a relationship that led to our creating the Sophiaphilosophy program on BloggingHeads.TV in 2014. Massimo had an assistant over at Scientia Salon, Daniel Tippens, an NYU philosophy student, with whom I also developed a close friendship. When Massimo decided to close down Scientia in 2015, Dan and I thought it would be a shame to waste the community that he had created, so we started up The Electric Agora out of Scientia’s ashes. Its focus was entirely different, of course – Scientia was all about the intersection of science and philosophy, while The Electric Agora is much more eclectic, spanning everything from philosophy to literature, politics, education and even humor – but at least at our initial launch, we began with much the same audience. Indeed, we brought several of the other regular Scientia commenters – E.J. Winner, David Ottlinger, and Mark English – on as contributors. Today, they make up the core writing team, along with me and others who appear on a more one-off basis. (Others have joined the team, here and there, but only this core group has lasted for the duration.) Dan Tippens stopped working with us, when he entered a Ph.D. program in philosophy, himself, and I won’t deny that I miss him terribly.

In terms of why I decided to do it, I would like to say it was in the service of some noble idea or duty, but the truth is that I was beginning to find working exclusively in the professional academic framework unsatisfying. For one thing, there was the realization that it is quite rare that one has any sort of real influence on the course the discipline takes, and I discovered that I had little interest in merely adding grains of intellectual sand to a vast beach. For another, I came to understand that the expectation was that I would just keep banging away at the subjects I had already written on, and as I said in my Philosophy Now essay, I think that this brings severely diminishing returns. Most significant philosophical questions do not have definitive answers, and there really are no “correct positions,” other than for the ideological captured (about whom we might talk later), so what one does is stake out the positions one thinks are best. The most interesting and productive forays into any of these areas, then, are the initial ones and those that come a few rounds after, but beyond that, more often than not, it becomes an exercise in pedantry and serves mainly to pad resumes and pursue professional advancement. Beyond this, as a purely personal matter, while I am interested in a broad variety of subjects, I am not interested in pursuing any of them to the ends of the earth: it’s just not my temperament. Finally, I grew tired of being forced to remain within the very rhetorically and stylistically deadpan template required for academic publishing today. I felt that I was really growing as a writer and was finding as much pleasure in the wordsmithing dimension of writing as in the content, so I wanted to write in a context in which I could retain creative discretion and control.

As for whether it is important that philosophers communicate their ideas to the public, I guess it’s a matter of which ones. There are some – too many, in fact – that I wish would never speak to the public at all – or to anyone for that matter – so I couldn’t answer this question in a general way.

3:16: In this role you are pretty much involved in a lot of the controversies of the contemporary philosophical and cultural/political scene. So let’s look at your take on some of them. Firstly, there’s the issue of the assault on liberal ideas in politics from both the radical left and the alt right. You’ve got Trump and we’ve got Brexit! How do you see this situation? Is it real or just an illusion produced by the new ways that ideas and news are manufactured via social media and the internet generally?

DK: I’m not sure I think that Brexit belongs in this conversation, and for the record, I am not generally a fan of supra-national/international governments, courts, etc., but I am not a UK citizen, so my views on it really don’t matter.

I do think that we are witnessing a substantial illiberalism in the West today and that it is ultimately a non-partisan development, insofar as we see it on both the Left and the Right. Incidentally, I think that “Left” and “Right” are increasingly meaningless in today’s politics, as we are in the midst of a substantial realignment, for many of the reasons Steve Davies gives in this fascinating talk.

So what is it that we are turning away from, whether on the Left or the Right? A number of core elements of what I would call the “liberal consensus”: (1) that the main purpose of the state is to make it possible for people to pursue their respective conceptions of the good; (2) that people should be able to think, speak, and act as they like, without interference either from the government or their fellow citizens, constrained only by a narrowly and concretely defined version of the harm principle; that (3) consequently, we should err on the side of freedom of speech and association, especially for those with whom we most strongly disagree or disapprove; (4) that our engagement with those with whom we most strongly disagree or disapprove should remain in the realm of argument and never involve attacks on their reputations or livelihoods. I should add that my reasons for holding this view are as much, if not more a matter of prudential considerations than theoretical ones, as I agree with much of the theoretical critique of liberalism, along communitarian and other lines. Like so many things, liberalism strikes me as the worst political philosophy, except for all the others.

People often ask me why I spend so much more time criticizing the Left’s illiberalism than the Right’s. My reason is twofold: (1) I am a liberal and my first duty is to insure that my own house is in order; and (2) the Right has always been opposed to liberalism (part of the reason why so much of the so-called American Right really is nothing of the sort), while the Left’s illiberalism is the result of a proverbial civil war within the (in the American context) Democratic party, with the progressive wing being ascendant since the McGovern campaign, with some notable exceptions, such as Bill Clinton. I view this as a catastrophic development for the party, not just because I think the progressive tradition is far less distinguished and far more problematic than the liberal one, but because I think that in the US, it is an electoral loser and may doom Democrats to Electoral College losses in perpetuity, if not checked, given the way in which we tend to be clustered geographically in a handful of major metropolitan areas.

3:16: Do you think there are resources, traditions and such like, within philosophy that we can draw on to understand and manage this situation?

DK: I would, were it not the case that the core institutions of philosophy and the younger generations of philosophers are among the most committed to the abandonment of the liberal consensus, as is the University, more generally. (The latter is particularly dangerous, given the role the University plays in our society.) And beyond the reasons I gave in response to your previous question regarding my public intellectual work, this is another reason I have wanted to do less and less work within the frame of professional, academic philosophy: it has been ideologically captured and thus, compromised, and is not something I want to be involved with, to the extent that I can avoid it. Recently, I called for the creation of a rival professional organization to the APA, to which all the sane, reasonable people might flee, but while there was a lot of sympathy expressed for the idea, it gained zero traction.

[Descartes]

3:16: You’ve engaged with philosophers who say that western philosophy itself is damaging because it feeds racism and sexism? Why do you disagree with these people who say that the way Anglo-American philosophy as practiced is racist? I’m thinking about your recent disagreement with Crispin Sartwell who argued that mind body dualism is analogous to racism. What was Sartwell arguing and why did you think this was a distortion of the Western philosophical tradition?

DK: It is incontestable that Western philosophical ideas and theories have been directly responsible for bigoted ideas and practices. That is likely true of every philosophical tradition, to some degree or another. But Crispin’s argument in that dialogue – and I should say that Crispin has become my most regular interlocutor on Sophia, because I admire him as a philosopher and as a person (and because Massimo and I did so many that the well began to run a little dry) – was much stronger than this: specifically, that the fundamental, core metaphysical and epistemological ideas in the Western tradition are responsible for racist ideas and practices, and this I find objectionable on a number of grounds: (1) As I argued in the dialogue, it involves a revisionist approach to the history of ideas – Descartes’ dualism, which Crispin focuses on, is a product of his materialist/mechanist conception of physicality and has nothing to do with racism; (2) It involves a kind of guilt-by-very-indirect-causality logic ( X is racist/sexist/transphobic/etc., because some other person, somewhere, sometime used X to further racist/sexist/transphobic ideas or practices) to which I strenuously object and which is being used to destructive effect by those who want to drive gender critical feminists and gender critical feminist ideas out of the current conversation on sex and gender; and (3), relatedly, it comes at a time when these sorts of arguments are being used in what I take to be a very unhealthy and damaging iteration of the culture wars; one that in my view is in the process of destroying not just the traditional civil rights coalition, but the liberal consensus more broadly.

3:16: You’ve also become engaged with the hugely toxic debate between feminism and trans. Now I get a lot of trouble just asking this question in this way because I’m not being nuanced and I’m being biased and so forth. But I do think it’s toxic because I can’t think of any other area of philosophy where protagonists on one side of a disagreement are being unbelievably threatening to the other. And it’s feminist women that are being threatened! So how do you understand the debate and why do you think it’s become so nasty?

DK: Let me first say something about how I got into all this, which was largely by accident. Given who and what I am, I have very little stake in this conflict: I’m not trans; I’m not a feminist, though my life is filled with women – mother, daughter, wife, mother-in-law – who mean the world to me, and I support many feminist principles and ideas; I’m not part of the LBGTQIA+ “community,” if there is such a thing, which I doubt (‘community’ strikes me as an especially abused word lately); I’m not particularly interested in applied Ethics, beyond what I do as a teacher. There’s really no reason why I should have started weighing in on this at all.

My entry point into the set of issues and conflicts was Kathleen Stock, of the University of Sussex. Kathleen’s primary research area is in Aesthetics, and she used to be a central player in the British Society of Aesthetics’ annual meetings. (Maybe she still is. I don’t know.) I have worked in Aesthetics myself, and in the early 2000’s, I gave papers at BSA meetings five years in a row, which means that I watched Kathleen give papers, fielded questions from Kathleen on my own papers, socialized with her at the various boozers and banquet dinners that are a part of every academic conference, etc. While she was never a personal friend and hung out with a different “clique” within the BSA – some of whose members I think disliked me quite a bit, though I have no idea whether she shared their aversion or not – if you’d asked me at the time whether I knew her or was a colleague, I would have said “yes.”

Fast forward to today, and having neither seen nor really thought of Kathleen for over a decade (she mostly works in different area of Aesthetics than the ones I have tended to work in), I suddenly begin seeing her name all over the place. Turns out she’s at the center of efforts to resist some of the more lunatic policy and regulatory initiatives of the current crop of gender-identity activists, including the call to eliminate single sex intimate spaces, sex segregated sports, and sex segregated prisons, to name just a few, and all of which becoming truly serious problems when wedded with the effort to push “gender self-identification” legislation in the UK, which will be coming soon to a country near you. I saw Kathleen being abused and attacked across the philosophical landscape for taking a critical (aka “sane”) position with regard to all of this, from the pages of the American Philosophical Association’s Blog, to Justin Weinberg’s (don’t even get me started on that guy) industry-insider blog, The Daily Nous, and philosophy Facebook and Twitter. The only one with a platform who seemed to be defending her was Brian Leiter, so my inclination was to throw what platform I had behind her as well, for reasons of collegiality and the kind of loyalty I am always inclined to extend towards those with whom I have history.

Once in the fray, I became more interested in the subject, both intellectually and as a matter of social policy, and convinced that gender-identity theory and activism was not only a serious social threat – I defy anyone to look plainly at what is going on with the “transitioning” of young children and adolescents and come away thinking that it’s anything but a disaster – but that it is going to destroy the civil rights coalition, which it is in the process of doing, with lesbians feeling increasingly alienated from the coalition and traditional feminists (calling them “radical feminists” is just stupid, insofar as their feminism is no more radical than that of Marlo Thomas’s 1972 made-for-children album/film, Free to Be You and Me) being thrown out of it entirely and lumped together with Trumpers and other assorted right-wing troglodytes. The greatest tragedy of the latter is that it is largely at the hands of other, usually younger feminists, who seem to have seriously lost the plot. Less tragic, though equally awful, is the role being played by young, bearded, “woke-bro” types, who seem never to pass up an opportunity to make themselves as loathsome as possible. Watching these puny twits attacking women, calling them “terfs” and “cunts” and the like makes my blood boil.

As for the “why” of it, I’ve been trying to work this out in a series of essays, and what I’ve concluded so far is that it is the result of a number of forces that have come together at this particularly shitty point in time: accelerating social atomization; extreme deformations of the liberal conception of the self; wild, over-the-top conceptions of autonomy; a very weird and unhealthy conception of embodiment; and a combination of some of the worst developments in social media culture. My views on all of this are still forming, but people who are interested in a bit of a deeper dive can check these out:

3:16: Do you think that there are some issues that philosophy shouldn’t ask questions about – and are there some questions philosophers need to be careful about raising – for example, I would never ask whether a foster parent is a real parent in real life – that would be a horrible thing to do - even though in a philosophy seminar I might but be very conscious of the foster parent who might be in the seminar room?

DK: As a general matter, no. And with regard to your example, I would think that the question of what constitutes a parent and how we should understand the various varieties that fall under this heading – birth, adoptive, foster – and their relationships to one another is exactly the sort of thing that philosophers should talk about. And I should mention that I happen to be adopted myself.

3:16: Another issue you’ve discussed is Peter Singer’s approach to utilitarianism. Can you sketch for us what you take Singer’s position is and why you push back against it very robustly?

DK: My objection to Singer has a number of layers. At one level, it’s very much in the spirit of Susan Wolf’s arguments in “Moral Saints.” The idea that our moral duties are always overriding of every other consideration (what I’ve called the “morality everywhere” view), to the point that everyone is morally required to live just above the level of a Bengali refugee (for which Singer argues in “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”), not only represents a catastrophic misunderstanding of the human condition, but recommends a world that clearly would be worse (in the sense of less appealing) than one in which people expended resources on the cultivation of virtues beyond moral ones. I don’t want to live in a world in which there are no master chefs, world class composers, or Wimbledon champions and neither does anyone else (at least, if they are being honest), but this is exactly what a view like Singer’s entails, if you actually take it seriously, as opposed to simply as a rhetorical performance (which I’m increasingly inclined to think is what it really is). At another level, I really dislike moralizing and preaching, as they inevitably lead to ugly hypocrisies, insofar as the moralizers and preachers are human. So, when it turned out that Singer, who has written on behalf of active euthanasia for people who are at the end of the proverbial road, spent thousands upon thousands of dollars on his mother’s Alzheimer’s care, the right conclusion for him to have drawn would have been that his philosophy must have gone off the rails somewhere, but instead, he chose to hide behind weakness of will, which strikes me as dishonest and weasely. Finally, Singer’s brand of Utilitarianism represents the ultimate form of prescriptivism in moral philosophy, and I am of the view that moral philosophy is fundamentally descriptive, for the sorts of reasons that W.D. Ross gives in The Right and the Good(about which I’ll say a bit more, when we talk about my favorite philosophical books).

I should mention that I discussed Singer and these other issues at some length with Robert Gressis of Cal State Northridge, on Sophia. I also took it up the “morality everywhere” issue in an essay over at The Electric Agora and in a dialogue with Dan Tippens on Sophia.

[Danto]

3:16: Philosophy of art is one area where you’ve written. You’ve defended Wittgenstein’s approach to art against a New Wave approach to philosophy of art. So first can you tell us what this New Wave was and what brought it about? And what is it, and why do you think the Wittgensteinian approach still a better approach? Are you a card carrying Wittgensteinian across the board?

DK: Ok, first on the “New Wave.” I have used this term to characterize the efforts to define ‘art’ that came after what I’ve called the “Wittgensteinian interruption” of the mid-20thcentury, a brief period in which anti-theoretical work in aesthetics was dominant. (I’m thinking of essays like Morris Weitz’s “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics” (1956) and William Kennick’s “Does Traditional Aesthetics Rest on a Mistake?” (1958).) The archetypes of the New Wave include the Institutional Theory of art, pioneered by Terry Diffey, in “The Republic of Art” (1969), the “Interpretism” of Arthur Danto, most fully expressed in his Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1980) (people have called Danto an institutionalist, but he demonstrably isn’t one), and the “historical” theory of Jerrold Levinson, as articulated in “Defining Art Historically” (1979).

The brief period of anti-theory – the “interruption” – was the result of several forces coming together: (a) cumulative intellectual exhaustion, as one definition of ‘art’ after another was rendered anachronistic by art history; (b) specific art historical developments, such as the Readymades, which seemed definition-defying; (c) the realization in the philosophy of language, largely fueled by the later Wittgenstein, that many, if not most terms do not admit of explicit definition or even of analysis in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.

The reason why the “interruption” was only temporary was due, in good part, to the idea, articulated in Maurice Mandelbaum’s “Family Resemblances and Generalizations Concerning the Arts” (1965), that in considering whether a term or concept is definable or analyzable in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions, one must consider not just the exhibited or manifest qualities of the thing in question, but its relational qualities as well. For example, if one only considered the exhibited qualities of Prime Ministers, one might conclude that ‘Prime Minister’ is undefinable, but one would be mistaken, insofar as the term can be defined in terms of a set of institutional relations. Taking Wittgenstein’s example of games, Mandelbaum wondered whether, perhaps, ‘game’ might be definable in terms of relational characteristics, even though it would seem not to be definable in terms of exhibited ones. This is the insight that defines the New Wave, and all the theories that belong to it attempt to define ‘art’ in terms of relational characteristics.

All of this is tremendously clever and gave new life to a brand of theorizing that had been presumed dead. The trouble is that the core problem that led to the “interruption” remained, namely the inherently progressive nature of art history, and just as that history demonstrated that the exhibited characteristics of art inevitably would change as art developed over time, it also demonstrated that the relational characteristics of art would change as it developed over time as well. Hence, my somewhat lonely, ongoing commitment to an anti-theoretical posture, when it comes to defining ‘art’ or analyzing it in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions.

3:16: Are you an Aristotelian when it comes to the critical evaluation of artworks – why do you think it’s possible to offer straightforward critical evaluations in the absence of critical laws? And does this approach carry over into your approach to ethics - I'm thinking of Anscombe here and virtue ethics type stuff?

DK: No, I am not. I am an anti-theorist in this area as well, which means that I don’t believe one can give a theory of critical evaluation nor should one. Like the “investigative” model of criticism articulated most expertly by Arthur Danto and criticized most effectively by Susan Sontag, which I wrote about in a 2012 paper, “Interpretation and the ‘Investigative’ Model of Criticism,” I think the “evaluative” model of criticism is mistaken and more of a philosophical conceit than a serious portrait of what criticism is or what critics do.

The view of critical evaluation that you are referencing is articulated in two papers, “Normative Criticism and the Objective Value of Artworks” (2002) and “Critical Justification and Critical Laws.” (2003) I still think that these papers are largely correct, but, my views have changed substantially as to what they imply or even suggest. To the extent that one can make “objective” evaluative judgments about artworks, they are going to be Aristotelian in form, i.e.: “If artwork A sets out to do F and succeeds in doing F, then A is good, in that respect.” The trouble, of course, is that this doesn’t get you very much. For one thing, there will never cease to be disagreement over whether A succeeds in doing F, and that is in good part because whether A succeeds in doing F may be entirely a matter of taste and thus, subjective. (It also begs the question of why it is good to be good in such a respect, which, obviously, cannot itself be answered teleologically.) At the time, I was trying to see if there was a way out of the antimony of taste as characterized by Kant and Hume, and going teleological was the move I thought would get me out of that cul-de-sac, but at this point, I am convinced it is inescapable: a feature, not a bug.

3:16: Drawing all this together as a take home, can you summarise your philosophical positions regarding politics, culture and philosophy – would the label Aristotelian Wittgensteinian capture you?

DK: I don’t think I can summarize my views in a formula or by reference to a handful of figures. The best I can do by is identify some of the key elements of my philosophical outlook, which will pair nicely with the next question you ask about books.

--Neither psychological nor social kinds can be reduced to or eliminated in favor of biological or physical ones. Hence, I am a metaphysical pluralist.

--Psychological and social things clearly exist, so I am a realist about them.

--Metaphysical pluralism/realism does not imply supernaturalism, Platonism, Cartesianism, or “woo” of any kind.

--What counts as epistemic warrant is ultimately inquiry/framework relative.

--Meaning and representation in language is irreducibly social in nature and consequently, cannot not grounded in the mind (or brain).

--Agency is inherent to the concept of an action.

--Reasons are not causes, in the scientific sense of the latter.

--Values are subjective.

--Moral imperatives cannot be rationally justified.

--Moral imperatives do not have any sort of intrinsic force.

--Moral obligations are particular and circumstantial.

--The language of moral obligation, as used in public, as well as much of our personal discourse, is mostly rhetorical and manipulative and always should be treated with great suspicion.

--There never will be widespread consensus on what constitutes the good in large, pluralistic societies, so a procedural liberalism is necessary for modern societies to remain intact and internally at peace.

3:16: And are there five books you can recommend to the readers here at 3:16 that will take us further into your philosophical world?

DK: I have been as influenced by papers as by books, so I hope you won’t mind if my list includes five of each (with one little cheat of a twofer). I also should say that I am listing things that had a very profound and specific effect on the course that my work has taken and left off things that were influential on me, but in a more general, orientating sort of way, like Hume’s Treatise or Locke’s Second Treatise of Government.

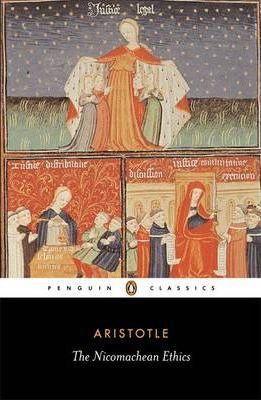

1. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Obviously one of the central, foundational texts in the history of Western philosophy. Also likely the most famous example of virtue ethics. Some of what I think are among the more important takeaways: (a) rational investigation doesn’t get you very far with regard to virtue, not really going beyond “the right thing to do/best way to be is that which involves not too much and not too little”; (b) that what constitutes too much and too little is context dependent; (c) that ultimately, one must see it, which Aristotle expresses through a very brief, but essential metaphor, involving how one determines whether bread is suitably baked; and (d) that virtue and vice defy anything but the most generic generalization.

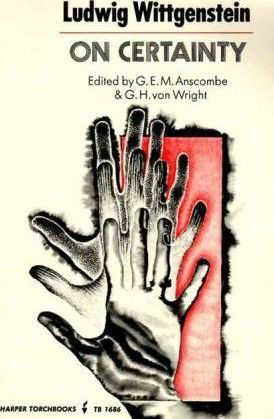

2. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations; On Certainty.

The greatest work(s) in philosophy since Kant and completely paradigm breaking. Philosophy should have changed forever in the wake of these post-Tractatus works, but philosophers were too invested in the professional bloat effected by disciplinization and simply ignored the arguments, rather than seriously contend with them. Two greatest takeaways: (a) representation – and hence, all meaning – is intrinsically social and thus, irreducible to the mental; (b) all justification is inquiry and framework-relative, which means there can be no general epistemology or theory of warrant and skepticism can only constitute a kind of “stress test” instrument, but never an actual position.

3. W.D. Ross, The Right and the Good

In my view, the best work in moral philosophy prior to the Second World War. It decimated both (a) criteria-based theories of obligation (which is pretty much all of them); and (b) the prescriptivist approach to moral philosophy. Also one of the most realistic treatments of obligation ever written: Obligations are directly felt, not inferred or deduced; actual obligation is a matter of which of many “prima facie” obligations is most pressing, given the circumstances; one can get this wrong; and theory can neither change nor otherwise correct that fact. Sounds about right.

4. Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind

Even if the Logical Behaviorism that it supposedly represents (and I’m not sure it really is “theoretical” in that way) is a dead-letter, so much of what is articulated here is just spot-on, and the writing is clear and straightforward and yet, stylistically a pleasure. From the fact that behavioral verbs refer to behavioral activity one cannot infer that mentalistic verbs refer to mentalistic activity is, of one core insight of this book. That it is a mistake to think that because an action is deemed intelligent or otherwise competent, it must be the product of some prior act of intellection or competent thinking is another. As a whole, the book is one of the key elements in putting together a thoroughly anti-representationalist, anti-mentalist philosophy.

5. Arthur Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace

The only truly great work in the philosophy of art to come out of the New Wave, and the only theory that ever had a chance of convincing me. Even if ultimately unconvincing, however, the book involves a level of erudition, originality, and good writing that is exceedingly rare in philosophy. One of those things about which I can honestly say, “God, I wish I’d written that.”

6. Elizabeth Anscombe, “Modern Moral Philosophy”

A work that like the Investigations/On Certainty, should have forever changed the discipline, but which ultimately was ignored because philosophers were too invested in the institutional dimensions of the discipline. Quickly and efficiently, Anscombe demonstrates that the modern conception of moral obligation depends upon source ideas that we no longer accept: (1) that reality is “morally thick” in the manner conceived by Aristotle; (2) that moral obligation has the sort of force one finds in law. She recommends, consequently, that we stop doing moral philosophy until we work these things out, but, of course, no one listened, which is why so much of the work in the area since then is, as far as I am concerned, pretty worthless.

7. Wilfrid Sellars, “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man”

If you’d asked me to make a list consisting of just a single element, this would have been it. Even more than Wittgenstein, I think, Sellars provides a framework from which not only to understand virtually every problem that arises in philosophy, but also from which to understand why some of them really aren’t problems after all. If one actually understands the distinction between the Manifest and Scientific Images, as well as what Sellars means by a “stereoscopic vision” consisting of the two, one will never be tempted by reductionism, eliminative materialism, ontological monism, naturalized ethics, determinism, or any number of other mistaken views. That so many philosophers are so tempted, while simultaneously claiming Sellars as an influence (people as far apart as the Churchlands and Richard Rorty both claim him), suggests that few of our philosophical notables have really understood the paper.

8. Jerry Fodor, “Special Sciences (or the disunity of science as a working hypothesis)”

The most significant, devastating expression of anti-reductionism in philosophy. Philosopher should be required to memorize it before engaging in any work in the philosophy of mind.

9. Susan Wolf, “Moral Saints”

Wolf articulates one of the main reasons to reject the “morality everywhere” view that I have mentioned earlier and explains why no one really wants moral considerations to override every other, at all times, and in all places, regardless of what people might say. Ethics strikes me as the area in philosophy where philosophers are the most likely to be dishonest – either deliberately or inadvertently – and Wolf’s essay is a great tool with which to pierce through that dishonesty.

10. Bernard Williams, “The Human Prejudice”

Bernard Williams is one of the greatest of the post-WWII philosophers and especially, in ethics. More effectively than anyone, he demonstrated the extent to which ethical principles and practices are an expression of human nature, rather than any sort of rational structure that floats above them. This essay is one of his most compact, clear expressions of this idea.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees