Autonomy, Kierkegaard, Global Politics

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I agree with much in Susan Wolf’s characterization (although in one early work she unfortunately used the “autonomy” label for leeway-liberty, with Sartre and other existentialists in mind too). She saw value in Frankfurt’s idea that autonomy is connected with shaping our own motive repertoire, including our cares. I have gone a little further and suggested that existential autonomy is the freedom-condition of responsibility for character, self, or practical identity, just as some kind of rational control (perhaps with leeway) is the freedom condition for morally responsible action in general.'

'Kierkegaard’s critique of aestheticism amounts to refutation of the widely held view that a completely amoral person can be personally autonomous. Kierkegaard and Nietzsche never knew each other, but some of Kierkegaard’s themes are a direct challenge to Nietzschean views, and thus also to such 20thcentury thinkers as Bernard Williams, whose Gauguin is supposed to be an autonomous aesthete or amoralist.'

'The right explanation is that autonomy-enhancing sources must attune us both to values in the world and in ourselves, moral obligations and our unique potentials. Existential authenticity should, then, be understood as a higher kind of personal autonomy that includes some originality in response to goods with universal significance, given our unique persona and situation – defining our individual calling, if you like.'

'Although Kierkegaard never developed such a metanormative theory, my existential version aligns with his arguments for a modest kind of personal autonomy founded on sources of authority that we do not arbitrarily choose or create by fiat – namely goods that authorize action and choice by providing objective practical reasons for them.'

'Russia itself would probably be more like Japan and Germany today if a large Marshall Plan-style effort to secure its future had been made in the early 1990s when Russia desperately needed help on this scale. Instead, we have a regime that rules through biker gangs wearing black shirts, kills and imprisons opposition politicians and journalists, openly promotes white supremacism, increasingly threatens more of its region, hacks American elections, and keeps the most bloody tyrant of the 21stcentury in power in Damascus.'

'Whenever a few nations pay all the costs to stop mass atrocities, or to bring a terrible civil war to an end, or to reconstruct a nation after such events, or restore rule of law and honest civil service to prevent kleptocracy and corruption, many other nations benefit directly and indirectly from the resulting institutional and human capital but pay nothing for it. They are free riders.'

'R2P says that all necessary measures may be used to stop mass atrocities that are already underway, as well as mass ethnic cleansing and persecution, even in the context of civil conflicts. This was a fundamental reform because the UN had, before this, limited intervention to cross-border war, and sought to deal with war crimes and crimes against humanity mainly through judicial procedures (e.g. tribunals) long after the fact.'

John Davenport has published widely on topics in free will and responsibility, existential conceptions of practical identity, virtue ethics, MacIntyre and Frankfurt, motivation and autonomy, theories of justice, and philosophy of religion. Here he first discusses personal autonomy, the narrative theory of identity, Galen Strawson, the link between narrative theory and autonomy, existentialism, Susan Wolf's ‘deep responsibiliy’, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, the hierarchical conception of autonomy , the existential diagnosis of inauthenticity, links with work in action theory and moral obligation, Kierrkegaard's narrative theory of unity as a version of virtue ethics. Then he discusses whether outsiders should interfere with internal politics of other states, global justice, the ‘free rider ‘ problem, the R2P doctrine and finally the importance of Habermas to his approaches to these issues.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

John Davenport: I originally became interested in philosophy due the “problem of evil” – whether the wrongs and harms we find in this world are compatible with creation by a good God. I knew people who clearly needed some kind of an answer to this haunting question. But I have published almost nothing on it; the issues involved are very hard indeed. It did lead me to free will and autonomy.

After starting on this issue around age 15, within a couple years I conceived what seemed then like a bright idea: solving the problem of evil would be good, but it would be even better to figure out what the root causes of moral evils are and stop them at their source. History since then will tell you what became of that absurdly grandiose ambition. Maybe this explains why questions about human rights and mass atrocities have always been with me, although I’ve only written on them more recently. Maybe mine was a very unusual way into such a contemplative field; I don’t think most philosophers begin with a desire to “change the world.” Maybe that’s a good thing.

3:16: You’ve looked at various philosophical questions via a broadly existential prism. One area you’ve been interested in are the notions of autonomy, practical identity , self and character. Analysis of personal autonomy has flourished in the analytic tradition for four decades – Harry Frankfurt and Gerald Dworkin are parade cases I guess. Before looking at your distinct approach, can you sketch for us the pre-20thcentury history that leads in to this contemporary scene and in particular how the notion of autonomy moved from just moral self-governance to something broader? Who were the main philosophers developing this change?

JD: Right, this expansion of “autonomy” to include other personal ends and values besides moral requirements is perhaps the most lasting and deep effect of the Romantic era – even beyond cultural movements towards romantic love that pre-19thcentury novelists had already valorized. I maintain that Kierkegaard anticipated much of the 20thcentury developments in personal autonomy theory. While he was focused on the effects of accepting moral duty and the challenge of religious revelations (and experiences), he took from other romantics a clear sense that our personal loves for particular people, artistic achievements, and even cultures and nations are what first give ‘content’ to our self in the practical sense. In short, we have to will something concrete, in the form of cares or ground projects, to become someone for whom morality and then potentially religious callings can matter in a personal way – as something we affirm from the core of who we are, rather than simply finding them imposed on us by force or fate.

Some have argued – Sarah Broadie comes to mind – that Aristotle already had something like a proto-notion of autonomy, both in his conception of rational choice and his idea that we can (to some extent) shape our own character through devotion to “noble” (kalon) goals and priorities. Clearly, as Foucault has argued, this idea of self-cultivation through a breadth of interests in worthwhile things (activities, aspirations, persons) had a long history after the immediate post-Socratic area, but it can hardly be said that themes anticipating personal autonomy were widely emphasized in late antiquity and medieval Europe. Some recent arguments have traced existential conceptions of selfhood to the ascetic tradition and pietism, given their emphasis on self-control and sculpting of one’s motives. But these do not amount to thinking of oneself as an artwork that can be more or less interesting, beautiful, or noble in manifold respects.

In my view, Rousseau’s importance in moving personal autonomy onto the agenda cannot be overstated. Charles Taylor is correct about this. I have not had the chance to write much on Rousseau, but his reconception of educational goals and methods speaks volumes in this regard. As one of my undergraduate professors rightly stressed, one can tell a lot about someone’s picture of practical identity and goods realizable in personal existence through their sense of what education should accomplish. How Rousseau got to his ideas from a strict upbringing in Geneva still eludes me, but ideas from the Italian Renaissance had been circulating and gathering audiences. In the early 1700s, humanist thought passed a kind of threshold beyond which personal aspirations beyond duties to one’s communities could become a main focus. A cynical analysis might say this ‘luxury’ only became socially possible due to economic growth, but the expansion of print stories about a wider variety of people’s lives – including people who were not famous leaders – might be even more important in the explanation. An awareness of alternative lives, different kinds of pursuits and relationships, other roles and goals worth striving for beyond the socially familiar ones, is crucial for personal autonomy.

3:16: One of the ideas you develop is a narrative theory of identity, a theory that has been under fire by various contemporaries of late, perhaps most prominently by Galen Strawson. So can you say what thesignature thesis of the narrative theory of the self claims and why Strawson finds it a flawed model for understanding the self?

JD: Yes, the debate with Galen Strawson has been much on the minds of narrative theorists of late. Galen kindly emailed with me a bit while I was writing Narrative Autonomy, Identity, and Mortality as well; “episodic” or not, he was intellectually generous. My co-called “narrative realism” was developed in response to other objections from John Lippitt, Bernard Williams, Greg Currie, Peter Lamarque, and several others who emphasized that narratives are artifacts that require or invite aesthetic features that are not usually needed or helpful in real lives.

I have viewed this as the most fundamental challenge, which can only be adequately answered by arguing that our personal identities are not (at first, or primarily) artifacts of explicit “telling,” rendition, or reflective interpretation, and yet still have a narrative-like structure in several broad respects. A narravive– my neologism for the living narrative-like development of a practical identity – is metaphysically prior to autobiography and biography, but it has a cumulatively developing form that is like artifact-narratives in several respects that have ethical implications. Although our more explicit self-interpretations and self-expectations fold into and reform our tacit ongoing sense of what we’re up to (and up against), that awareness of a cumulative development is mostly prereflective. And there are many parts of a person’s life-experience that will never be reflectively thematized by them. Some of these moments or experiences affect the tenor or felt meaning of much else in that life: I call these “Rosebud” components of a narravive. In this way, the artifact objection or “life vs literature” worry is accommodated.

Strawson’s challenge is quite different, coming into this debate from the side, as it were. He argues that narrative conceptions of identity depend on a diachronic kind of consciousness, which is something like unity of apperception extended over time: you, the R* who is now remembering something that happened when you were ten, feels identical with the consciousness that had that experience at ten years of age – as it is now pictured in your remembering it. Strawson claims that not everyone is like that; he and others have a much more “episodic” consciousness. He may remember an experience from 20 years ago with a “from the inside” perspective, as if his body were at the center of action. Yet he – the present consciousness G* which is remembering -- feels no identity with the consciousness that had that experience in the past. So narrative theorists should not start from such biased assumptions about felt identity of consciousness over time.

In response, I argue that Strawson’s analysis implausibly implies that diachronic consciousness is derivative or even artificial. On his account, for example, diachronic continuity could only be something in the content of your experience at age ten that continues in the content of your present memory-process, and marks both as belonging to the same “you” – like the same watermark on all your personal stationery. Your experiences would be like a movie in which a little R* logo always appears in the upper-right corner; the original experience and occurent memory would both have this you-marker in their content. This is a very unlikely explanation of diachronic unity of apperception: it implies that diachronic consciousness is superimposed via contingent contents of experience on a form of continuity that in itself is simply episodic. The real truth or natural baseline would then be episodic for us all. So, while Strawson portrayed his account as merely neutral between these modes, or fair to both by treating them as equally natural, in fact he is implying something else entirely – and there may be no plausible neutral position.

The narrative realist should turn this implied charge around and say that episodic consciousness, if really innate in some human persons, is dysfunctional in a deep way, not simply ‘different.’ For example, it makes morally important undertakings like serious remorse much harder. After all, being episodic in Strawson’s sense means something much stronger than just being a sort of person who likes living the moment or going with the flow; these are dispositions of attention or cultivated aesthetic attitudes towards life. Rather, an episodic literally feels non-identical to the consciousness that experienced things through this same brain maybe a day or even an hour ago. If true, this might even deserve a DSM diagnosis; it sounds like a milder version of Cotard’s syndrome, a very rare condition in which people think they do not exist or are not identical with even their current experience. This deserves more investigation and lies beyond my competence, but should we say that Descartes’ experience and a Cotard-experience are both just as good?

On the other hand, maybe for some people, the non-identity feeling that Strawson describes is actually an artificial result of mental exercises and trainings, trying to live according to a certain ideology of mind – much as some masters of meditation are said to attain states in which they feel alien to their bodies. Strawson’s tendency to associate being episodic with being a spontaneous, carefree, or flow-happy person makes me suspect that it is at least partly a sophisticated practicalattitude rather than a basic form of self-consciousness, as he maintains. That’s to say I would apply some hermeneutics of suspicion here.

3:16: So what is it about the existential tradition that you think can contribute to this discussion about autonomy, the self and so forth? And presumably some existentialists such as Sartre and Nietzsche aren’t that helpful given that there accounts of self seem more fragmentary than narrative?

JD: While not all existential authors have shared a narrative picture of personal identity as developing cumulatively, with regresses and setbacks that only elaborate the ongoing story, virtually all of them hold that we can shape our practical identity through kinds of effort, or take charge of it to some extent. Alexander Nehamas thought that Nietzsche saw a life as potentially like a work of literature, although this was partly because of the artifice and aesthetic style that both can involve. Arguably the Nietzschean idea that (perhaps by a kind of bootstrapping) we can use some of our drives to corral and marshal the others into a single pervasive direction implies more to the self than a bundle of distinct impulses – although commentators disagree on this. For Sartre, there is still the idea of an “original project” that underlies and partly explains all our more particular purposes and valuations. This is an idea taken over from Kierkegaard that goes back to Kant’s noumenal choice of an ultimate practical orientation. There is at least a kind of virtual point at which the different lines of our actions and initiatives would intersect, a general purpose that would explain them. In Kierkegaard, this idea was developed in much more detail. Aesthetes, most of whom are wantons in Harry Frankfurt’s sense, are either tacitly trying to ignore the issue of whether they should care about anything, or more actively working to avoid having any concrete commitments. But, as we know, that inevitably amounts to taking a kind of stance, if not a stand. We are forced into having an embracing practical orientation one way or another. That’s part of what Kierkegaard’s theory of natural “stages” in personal existence means.

What this adds to a narrative theory identity are ways that a person can experience their ongoing narravive as more fragmented or more unified, and try to make it more unified if they will. This is how personal autonomy is manifested within narrative selfhood. Not every personal narravive has this feature. That’s why the constitutive level of narrative continuity is distinct from the achievement of richer depths of thematic unity that are associated with personal autonomy.

3:16: Can you make explicit the link between narrative theory and autonomy? And why do you say that personal autonomy – characterized by Susan Wolf as ‘deep responsibiliy’ and you see as ‘existential autonomy’- is still a broadly ethical concept even though it isn’t the same as Kantian moral autonomy?

JD: So the next question is partly answered, but autonomy theory since Frankfurt’s epochal 1971 article has often focused on structural or time-slice features of the autonomous agent (although Fischer and Ravizza considered the history of a person’s motives). I agree with much in Susan Wolf’s characterization (although in one early work she unfortunately used the “autonomy” label for leeway-liberty, with Sartre and other existentialists in mind too). She saw value in Frankfurt’s idea that autonomy is connected with shaping our own motive repertoire, including our cares. I have gone a little further and suggested that existential autonomy is the freedom-condition of responsibility for character, self, or practical identity, just as some kind of rational control (perhaps with leeway) is the freedom condition for morally responsible action in general. The term “autonomy” is used in many ways, but this I think it is this existential sense that people usually have in mind when saying that we have some rights to live according to priorities, values, and goals that we have a hand in shaping – as opposed to ones merely dictated to us, or generated by manipulation and brainwashing. This is a big topic! I’m revisiting it in writing on human rights just now.

3:16: Kierkegaard is the go-to guy in your account isn’t he? What makes him so important in this respect? And do you think that if Heidegger had admitted his influence more important thinkers would understand their own debt to him?

JD: Kierkegaard is incredibly important and under-appreciated. The whole idea of personal autonomy would not have advanced beyond Kant’s moral autonomy and the romantics’ aesthetic autonomy without Kierkegaard’s synthesis. His seemingly paradoxical idea of a virtual “choice” to become a serious choice-maker or committed agent is a watershed moment in the history of ideas. I came to this initially through Alasdair MacIntyre, who took it seriously, although I thought he had not correctly interpreted what Kierkegaard meant (to be fair, Kierkegaard is not always pellucid about what he means). If his view is defensible, then personal autonomy cannot float entirely free of ethical concern.

That means that Kierkegaard’s critique of aestheticism amounts to refutation of the widely held view that a completely amoral person can be personally autonomous. Kierkegaard and Nietzsche never knew each other, but some of Kierkegaard’s themes are a direct challenge to Nietzschean views, and thus also to such 20thcentury thinkers as Bernard Williams, whose Gauguin is supposed to be an autonomous aesthete or amoralist. It’s quite important if Kierkegaard’s account of personal agency and the flaws of “double-mindedness” managed to refute Williams’s position 150 years before Christine Korsgaard tried to. Of course, a Kierkegaard-inspired theory of autonomy can be stated without detailed reference to Kierkegaard’s texts – and if I live long enough, there will be a more detailed monograph on existential autonomy (a draft first chapter is online for anyone interested).

Heidegger was decisively influenced by the self-choice theme; it is reflected in his idea of authenticity as a stance attained only by some. He was also strongly influenced by Kierkegaard’s own critique of “idle talk” as a mask for chameleon-being, i.e. conforming to the mass and convincing oneself that one is a very subtle fellow for enigmatically hedging all bets. He also drew a great deal from Kierkegaard’s discussion of “earnestness” in the face of death. Heidegger was not too open about these debts, or a great many other things it seems. But, perhaps due to Nietzsche’s influence or the gaping ethical void opened by World War I (or both), Heidegger fatefully obscured the importance of ethical valuation in his analyses. Kierkegaard was actually clearer, I think, about the structure of Dasein in theSickness Unto Death– and about how this structure makes possible the various basic attitudes we see. “The ethical” is not an optional extra or merely a matter for “regional” ontology on his account; it is irreducible. In this respect. Kierkegaard is closer to Levinas than to Heidegger, even if the possibility of a better understanding remained in mitsein.

3:16: What is the hierarchical conception of autonomy and the existential diagnosis of inauthenticity – and why not start from these conceptions rather than from narrative theory and Kierkegaard? So what is Kierkegaardian wholeheartedness and how does it link, if it does, with accounts of narrative unity in MacIntyre and Frankfurt?

3:16: Frankfurt’s famous hierarchical theory, according to which personal autonomy results primarily from “identifying” with some of our desires for outward actions and their goals (by desiring to act on such first-order desires) also makes it seem like autonomy can be value-neutral. But this theory cannot stop a regress: our second-order desires would not be autonomous unless third-order desires identified us with them (and so on up the orders) because it does not qualitatively distinguish the kinds of motivation that are inherently autonomous without conferral of that quality. Kierkegaard’s accounts point towards the sense that commitment or resolve of the whole self – wholeheartedness in Frankfurt’s sense – explains this quality. But according to Kierkegaard, wholeheartedness cannot be sustained without attention to the goods involved in what we care about, and conflicts at this level are governed by ethical norms. For Kierkegaard then, wholeheartedness is a kind of infinite commitment or total resolve that grounds itself on ethical ultimates – or a highest good – that can regulate commitment to other goods and thus sustain us through deep changes in our projects and relationships.

If we examine experiences of personal inauthenticity, we find the same need for “strong evaluation” as a ground for our cares, as Charles Taylor argued. Standing for something, openly expressing what we value, remaining true to our personal commitments, critically evaluating these commitments rather than passively accepting them as formed by others, and tailoring their pursuit to unique life-circumstances all point back to the need to regard some goods as having objective importance – as King Lear famously realized at last when standing naked on the heath. Frankfurt’s hierarchical theory also cannot explain why some sources of motivation that might cause second-order desires, such as manipulation and brain-washing, are manifestly autonomy-undermining. The right explanation is that autonomy-enhancing sources must attune us both to values in the world and in ourselves, moral obligations and our unique potentials. Existential authenticity should, then, be understood as a higher kind of personal autonomy that includes some originality in response to goods with universal significance, given our unique persona and situation – defining our individual calling, if you like.

As beings with a cumulative sense of meanings, both autonomy and authenticity will be manifested within a narrative process. While Frankfurt’s hierarchical theory did not reflect the temporary aspects of human practical identity, MacIntyre’s account of personal lives as having narrative structures clearly does. What MacIntyre lacked was a clear explanation of how personal autonomy is connected with the virtues that he argues are necessary for practices, friendships, and long-term projects that must, on his account, be sustained through “constancy” and integrated into a single developing life. It turns out that personal autonomy involves a higher kind of narrative continuity beyond what comes automatically from being a person with normal human cognitive capacities (and that diachronic unity of apperception that Strawson denied). But higher-order volitions, formed and sustained through personal choice and striving – forms of will– are essential to this achievement of narrative integration. MacIntyre, like all eudaimonists, minimizes this crucial identity-shaping role of the will that the Franciscan tradition, Kant, and Kierkegaard rightly defended. The resulting account synthesizes what is best in MacIntyre, Frankfurt, and the Augustinian and romantic themes lying behind Frankfurt’s work (although he was no better at acknowledging his true sources than Heidegger was!).

3:16: How does your thesis link with work in action theory and moral obligation? And how does this link with your other project of understanding the existential theory of willing as projective motivation – are these two approaches complimentary?

JD: This synthesis – existential autonomy, in narrative form, including both objective ethical considerations as grounds and personal appropriation into a unique life-story – makes most sense when it is explicitly connected to positions in action theory and metanormative theory, although these were not among Kierkegaard’s main tasks. In action theory, the theory generally agrees with Kantian claims that there is a gap between combinations of belief/desire and intentions – as Korsgaard, for example, has argued. But the improvements on Frankfurt’s approach imply even more than this. We cannot explain narrative autonomy without recognizing that the human will does more than attend, deliberate, form intentions (some of which are intentions to omit), and try to enact them. It also combines, enhances, sustains, and alters motivations in the process of doing these other things, e.g. forming intentions and trying.

These self-motivating and striving functions help explain how we can set or “project” final ends that are not completely determined by our prior desires and beliefs about values to which our intentions may respond. They also resolve longstanding puzzles in favor of reasons-externalism, against the view that Humean view that we can only form intentions in response to motives that we already have (roughly, reasons-internalism). It is because Frankfurt was influenced by Bernard Williams Humean sympathies that he could not recognize this – despite coming close in a couple early essays – and thus could not complete his explanations of caring and love as inherently autonomous kinds of motivation. They have this quality due to the projective motivation they involve. Because Williams and Korsgaard do not recognize this ongoing volitional process of commitment and recommitment involved in striving, they cannot explain how identity-shaping forming, commitments, or “ground projects” are actively shaped by the personal agent (a reflexive process that gives substance to the very identity doing the shaping). Projective or striving will, along with the liberty involved in its commitments, is basically what Kierkegaard meant by “spirit” (And).

So the implications in action theory go pretty deep. I hold that this kind of projective motivation or striving will is indispensable for explaining several other phenomena, such as a moral will in Kant’s sense (or anything close to it), agapic love, divine creativity, radically evil motives, along with dedication to friends, loved ones, and the goals that define “practices” in MacIntyre’s sense. What psychologists have called “intrinsic motivation” as part of autonomy is better explained as projective motivation. This is also implicit in Viktor Frankl’s realization that self-actualization (a eudaemonist idea) is mostly a by-product of self-transcendence achieved in caring about goods beyond oneself for their own sake.

In moral theory, this position yields a version of constitutivism that is more defensible than Korsgaard’s (imho!). Like her version, it says that human persons are rationally committed to recognizing the inherent value of their shared human potential for moral agency and autonomous personal commitments (that are morally optional). But unlike her version, it holds that this inherent value is generated in part by the potential in different cognitive and emotional processes to recognize and respond to objective goods worth caring. Korsgaard was too influenced by Frankfurt’s approach to go this direction. You see the pattern: Williams and Frankfurt reject any commitment to morality rationally implicit in personal autonomy, and even when Korsgaard tries to restore this link, her argument accepts their Humean implication that our cares simply confer value on what we care about. Kierkegaard rejects this in Two Ages and related texts.

Although Kierkegaard never developed such a metanormative theory, my existential version aligns with his arguments for a modest kind of personal autonomy founded on sources of authority that we do not arbitrarily choose or create by fiat – namely goods that authorize action and choice by providing objective practical reasons for them. This alternative existential constitutivism will be featured in a chapter of my next book on Universal Human Rights. However, it only explains the most fundamental moral obligations, not the full range of ethical norms for character.

3:16: Kierkegaard comes out of Kant and dismisses Hegel’s ‘abstract speculations about Absolute Spirit’, as you put it, but he also draws on Aristotle too doesn’t he? So is your position regarding Kierrkegaard and his narrative theory of unity a version of virtue ethics?

JD: Yes, given what I just said, it is important to note that Kierkegaard’s ethics is not purely Kantian in its normative content or grounding (in fact he rejects Kant’s idea of self-legislation, although I think he misunderstood what Kant meant by this). Certainly there are some Aristotelian themes in Either/Or vol. II (as presented by the Judge, one of Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms). In my view, there are also Stoic and medieval virtue-concepts in Kierkegaard’s own “upbuilding discourses” and other signed works like “The Present Age” essay and “Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing.” Acedia and halfheartedness are condemned in numerous texts; patience, humility, purity of ethical and religious motivation (honed to the point of “infinite pathos”), and courage understood as “inner strength” in the face of difficulty are crucial for Kierkegaard. There is actually a significant debate within Kierkegaard scholarship – which has really flowered in the last 30 years – concerning whether his Protestant rejection of worth through merit and eudaimonism mean that we should describe his conception of character as alien to virtue ethics. I do not think so; the importance of inward spiritual “work” is stressed in Fear and Trembling and other texts; the Concept of Anxiety and Sickness Unto Death imply that we have to take some initiative through choice and effort; we cannot just wait in Quietist fashion for God to do it all for us.

Yet Kierkegaard’s conception of virtue is certainly a religious one, and ultimately a thoroughly Christian one in which agapic love has to transform every other kind of love. I’ve done some work on this relationship, which seems to imply that the virtues exemplified civil society, in love of family, in friendships, and even in romantic contexts are not fully virtuous – or they are even “glittering vices” – if they are not infused with a “love of neighbor” that is more radically selfless, willing to put aside one’s own agenda, not conditioned on reciprocity, and committed to a fundamental unearned worth that is equal in all persons. But this is still a kind of virtue ethics; Kierkegaard is more interested in dispositions of character shaped by choice (as well as our given temperament and circumstances) than in moral assessment of particular kinds of actions or policies.

3:16: You’re also interested in philosophical issues of contemporary global politics and your latest book addresses the mass slaughter in Syria which continues seemingly unabated since 2012. So this is a burning contemporary issue . The question you face is this: given that attempts to remove dictators and bad people from foreign power leads to their replacement with equally bad people or groups, outsiders should stop trying take down the bad guys. Qaddafi should have been left alone, the argument goes, because removing him has just caused chaos and more bloodshed. What’s your response?

JD: It might seem that my more recent political foci are a far cry from all the existential thought and autonomy theory we have been discussing. Yet, if there is anything to the infinite agapic demand, it seems like we must pay attention and act when mass atrocities are being perpetrated. This most basic justice is the very least that agapic ideals require of us. I have not forgotten why I went into philosophy, and there is an underlying method in the apparent madness of my many interests. A conception of free will and projective motivation can inform an account of personal autonomy, which – along with some basic moral norms supported by an existential picture of persons as freely responding to value – helps to ground a conception of human rights. I’m trying to put some of these pieces together in a new manuscript right now. Human rights, in turn, are essential to justifying a stronger transnational institutions needed to stop mass atrocities. Democratic global government will not stop all evils, but it is the only way to bring a permanent end to the worst political evils revealed in human history.

As your question notes, this may seem quixotic because the pendulum has swung strongly towards isolationism at the moment. The historical record is against this. Germany and Japan today are free and thriving societies that generally stand for justice; South Africa is on the way; the United States has also reformed through social reconstructions at several points. Bosnia, Kosovo, and East Timor are hardly perfect places, but they are not Libya, because they were reconstructed. At this point, social science can predict pretty well what post-conflict measures are needed to ensure that rival groups disarm, support a new central authority generally concerned with the good of all major sectors of a society, and so prevent the post-war situation from degenerating into chaos or a new dictatorship. These transitions require enormous resources and staying power from groups willing to help over a long period from 10-20 years. Only a very large coalition of nations can muster these kinds of resources without placing undue burdens on particular nations. That is one of the biggest reasons why we need a broad league of democracies today to manage reconstructions after dictatorships are overturned.

Most of our many mistakes in selectively opposing dictators have derived from the failure to assure adequate cooperation between able nations to do the job right and impartially – rather than for the political agendas or corporate interests of the intervening nations. To our eternal shame, we have not built the political institutions that are indispensable to secure global cooperation to these ends. Central to the necessary institutions is a strong league of democracies with many member-nations from all continents.

We know what happens if we rationalize that it is better to let tyrants carry out mass atrocities, as Tulsi Gabbard, Ted Cruz, Ed Miliband and many more naïve humanitarians advocated so stridently and fatefully in Syria: the rot spreads, the political cancer grows, and the threats become more virulent. Turkey and several European nations have been deeply affected by the monumental disaster in Syria. South America is now increasingly under threat from Nicholas Maduro’s mixture of military and mafioso kleptocracy, especially now that Russian intervention there has been encouraged by lack of forceful response. Russia itself would probably be more like Japan and Germany today if a large Marshall Plan-style effort to secure its future had been made in the early 1990s when Russia desperately needed help on this scale. Instead, we have a regime that rules through biker gangs wearing black shirts, kills and imprisons opposition politicians and journalists, openly promotes white supremacism, increasingly threatens more of its region, hacks American elections, and keeps the most bloody tyrant of the 21stcentury in power in Damascus.

The same applies to the Middle East. The rise of ISIS would never have happened if Iraq had been adequately reconstructed with true power-sharing between the three main groups, and Assad’s genocide had been stopped before itbegan to bury hundreds of thousands of its own citizens in the rubble of bombed buildings. The refugee flows into Europe might have been half their actual size in 2013 – 2017, resulting in a much more stable EU that could more effectively resist Russian threats. And Turkey, our NATO ally, would have been supported in the Syrian crisis rather than driven towards Russia instead. The bad consequences of inaction ramify on and on.

For comparison, if Qaddafi had won, slaughtering maybe 100,000 Libyans along the way, the hopes for democracy that are still alive and bearing fruit across north Africa today -- and now even in Sudan – would have been crushed out. People are quick to forget: Qaddafi’s goal was to spread the ideology of “Arab Supremacism” against “black Africans;” this was a major root cause of the mass slaughter in Darfur. His death was both intrinsically justice and a huge benefit to the wider region. Libya itself could be a stable consociation with popular support today if it had been reconstructed after Qaddafi.

In short, our errors in the years since 1989 are not due to the basic moral impulse to stop mass atrocities and resist Orwellian tyranny. If we stifle this decent impluse, we “blow out the moral lights within us” – Abraham Lincoln’s phrase for those who wanted to accept the spread of slavery for the sake of political peace. I would put it more strongly: if we are not willing to use hard power when that is clearly the only way to stop mass atrocities that are imminent or in progress, then our democratic societies will lack the inner spiritual strength to survive, and our children will reap the wind. Much of what we have in western nations today is due to the victory in World War II, but we cannot live forever on its dividends. Enormous evils are abroad in our world now, and they are growing in strength every day. If we do not meet them with all we have, then the only real opportunity for a just global order in seven millennia of recorded human history will be lost, perhaps irretrievably. If we are going to cause climate havoc and destroy the world’s biodiversity, we could at least secure for future generations a world that is not controlled by a cabal of tyrants.

3:16: You identify what you call the ‘free rider ‘ problem as something that needs to be overcome. So what is this, and how might it be solved?

JD: The free rider problem between nations is easy to understand in this light. Whenever a few nations pay all the costs to stop mass atrocities, or to bring a terrible civil war to an end, or to reconstruct a nation after such events, or restore rule of law and honest civil service to prevent kleptocracy and corruption, many other nations benefit directly and indirectly from the resulting institutional and human capital but pay nothing for it. They are free riders, just like people who jump the turnstile or cheat on their taxes. With too many free riders, any system to secure public goods falls apart or is riven by catastrophic incentives for the few parties who are doing their part to give up (or “defect,” as we say in game theory). For example, even with some help from a couple other NATO allies, the United States has had to bear too much of the cost to continue the struggle in Afghanistan. $1 trillion later, we seem ready to fold, let maybe 17 million women be re-enslaved by the Taliban, and thus betray millions of young Afghan men who put their hope in a better way. What will that teach reformers who are considering organized resistance to militant fundamentalist movements in other parts of the world?

We have seen these dynamics with respect to one global public good after another – starting with prevention of mass atrocities and failing states, but continuing to climate change mitigation, biodiversity, alleviation of the worst poverty, and many others. For example, the current harsh criticisms of the Brazilian government for encouraging a massive new wave of deforestation in the Amazon are correct. But few of the critics seem to realize that, because we all benefit from more of the Amazon remaining intact, the whole world should really pay most of the opportunity-costs of not converting (burning or cutting) it that now fall on Brazil alone. We all want to be free riders in this case, and the result is that the Amazon will be destroyed. Without an institution that can bind enough nations to do their part, eventually this free rider problem will lead to a pandemic disease spreading from one of the world’s poorest and most corrupt nations, killing hundreds of millions.

3:16: What’s the R2P doctrine, and why do you think it must become the heart of a new global order? Isn’t this just a utopian dream of a single world government?

JD: The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine that became international law in 2005 with its passage both by the UN General Assembly and Security Council is simply a legal endorsement of the basic moral impulse to stop mass slaughter and total tyranny, as I described. It was born from horror at the systematic mass murder of more than a million Tutsis and moderate Hutus in Rwanda. While it prefers prevention, R2P says that all necessary measures may be used to stop mass atrocities that are already underway, as well as mass ethnic cleansing and persecution, even in the context of civil conflicts. This was a fundamental reform because the UN had, before this, limited intervention to cross-border war, and sought to deal with war crimes and crimes against humanity mainly through judicial procedures (e.g. tribunals) long after the fact. This doctrine affirms, in effect, the moral principle that the international system has a duty to prevent these worst of all political evils.

In my view, R2P was the last chance for the UN Security Council to work. But before the ink was dry, China and Russia decided that R2P would only be a symbolic act; they would continue blocking forceful action to stop mass atrocities in almost every case – first in Darfur, and then in Syria, where the Assad regime has killed at least half a million people with help from Russian bombers. The UN Security Council is too structurally flawed to be reformed; its main effect has only been to prevent democratic nations from working effectively together to stop China and Russia from increasing their power to defend human rights. Their fig-leaf justification is that “multilateralism” requires this; in other words, “respect for sovereignty” requires that what is needed to stop mass atrocities can never be done – which is the exact opposite of R2P. If R2P were ever really implemented, eventually people in China and Russia would also demand democracy and civil liberties with impartial rule of law. So it is now crystal clear that mass atrocities can only be reduced through binding cooperation among nations in a democratic league: we have to stop giving dictators a veto over the collective will of democratic peoples.

But to do this, a league of democracies does not need to be anything close to a “world government.” In other words, it does not need to pressure every nation on Earth to join. If it were founded by (say) 40 nations and made moderately effective at its very limited tasks, then many other nations would want to join or at least secure friendly relations with the League within a few years. But many other nations could remain outside its framework, as long as they did not undermine its most crucial tasks by massive free riding. It could even work effectively alongside the many good United Nations organs, while mothballing the Security Council.

So the democratic league that I’ve proposed is not utopian in the senses of being either hopeless or dangerous. After the formation of the UN, when it became clear that the Soviets would prevent its working for a better world, even Albert Einstein joined Charles Streit and others to call for a league of democracies (on this topic, see R.S. Deese, Climate Change and the Future of Democracy). Now, when democratic nations face truly mortal threats from greatly emboldened dictatorial regimes, many thinking people living with the blessings of democracy recognize the need for much greater cooperation among our nations to overcome to freerider problems that are dividing us and stalling solutions to global problems. This just takes some political leadership – on the right, left, or centrist, I do not care which. At some point soon, even more of us are going to wake up and realize that if we do not present a wide united front to stop them, the dictatorship in China will spread its new Orwellian nightmare over more and more of the world; Hong Kong will only be the beginning. One day they might be emboldened enough by our weakness to invade Taiwan; after all, it worked for Putin in Crimea. Their big investments in developing nations will prove to be poison pills used to control more regimes in Africa and southeast Asia. And we’ll discover that our journalists, academics, and business leaders cannot criticize anything the Beijing regime does, for fear that our employers will suffer reprisals via cyberattacks or by way getting shut out of business with China. We will start to fear what this regime might do to our friends’ and relatives’ businesses, banking, or private information. This is no exaggeration, it is already happening!

In sum, a stronger political organization at a higher level of government always appears utopian until people realize that the alternative is dystopian in the extreme. So it was in the American colonies in 1776, and so it must soon be again among democratic peoples who are still willing to face enough reality and care enough about our future and our children’s prospects. It is terrible to realize that so many people living in western democracies just go blithely on their way every day, shopping and chattering online or seeking other entertainment, with almost zero sense that the freedoms they are used to may soon become impossible unless really dramatic political action is taken within a couple decades.

3:16: Habermas is a contemporary thinker you are interested in aren’t you? How much of your approach to political philosophy take from Habermas? What do you see as important in Habermas and where do you disagree with him?

JD: Yes, after Kierkegaard, I’m more indebted to Habermas than any other 19thor 20thcentury philosopher. I think his approach to discourse ethics and the right to democracy is basically on the right track. My conception of morality is more realist than his, but we both start from the principle that might alone never makes right; coercion is not justification. Against Nietzsche, the nature of human agency makes this so: we can appreciate practical reasons that are quite distinct from mere power, force, or luck. I also agree with Habermas that this demand for justification springs from an “axial” shift in human societies, although my conception of this paradigm shift is different than his (which I think remains more indebted to Jaspers’ controversial version). This will be explained in chapter two of my new book on human rights if I get it published.

This book will also defend a version of discourse ethics that affirms more of the classical Enlightenment grounds for moral rights than Habermas does. This follows from being more willing to accept findings in moral psychology, including the capacities involved in personal autonomy (both inward and as outwardly expressed in the world) as grounds for moral rights. This makes my account open, for example, to Martha Nussbaum’s suggestions about “central capabilities” needed for a meaningful worthwhile life. However, Habermas was correct, on my analysis, to regard human rights as connecting the moral and legal realms. It is not the form of modern law that, with the Discourse Principle, generates the basic categories of rights needed for any just governing system, as he has argued. But we can broaden this model to say that it is the linkage between certain moral rights and the need for coordination through both constitutional order and informal social norms/practices – e.g. to overcome free-rider problems – which implies the need for positive law (at national and global levels) that answers to moral grounds.

Within this “linkage framework,” we can deepen Habermas’s argument that human rights are neither pure “prepolitical” higher laws of nature, nor mere artifacts of convention or positive law. The human right to democracy follows almost as a corollary from this framework, because it is only through democratic processes that the constitutional order can legitimately give specific legal or social forms to the abstract rights that result from the general need for rational justification plus other substantive moral grounds. That’s a bit of a mouthful, but this analysis will show that the Habermasians have been correct to affirm, against Rawls and a majority of philosophers who have written on human rights since the 1990s, that there is a fundamental right to popular sovereignty. Indeed, I think that Habermas’s own principles should have led him to affirm the need for a league of democracies as well. But like so many others, he has been seduced by the promises of a “network” approach to global governance through NGOs and informal civil society groups that can never deliver even a 10thof the global public goods we so desperately need.

Kierkegaard might not have been pleased with all this systematizing and moral theory. But my old colleague Merold Westphal taught me that an agapic ethic cannot merely be an ethic of inwardness. It’s part of my own MO that an adequate agapic ethic should be able to include a conception of political justice, even while it recommends motives and devotions that transcend the secular orders in which justice is realized on Earth.

3:16: And finally, for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

JD: I’ve mentioned a few classic texts along the way.

Frankfurt’s collection, The Importance of What We Care About, has remained crucial for me; I’ve been trying to develop and improve ideas in that work for years.

I said little here about Fear and Trembling, but have written a few essays on this very influential book; working out its “eschatological” ideas has been a work of love for me, which shows that Kierkegaard never meant to recommend giving up moral motives to blindly obey divine power.

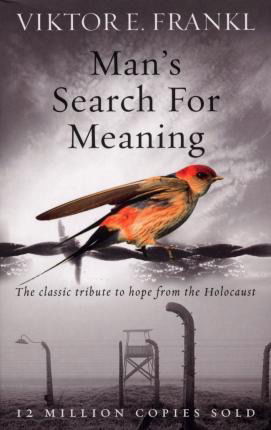

I’m also quite indebted to Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, which really shows how a meaningful life depends on values we find worth caring about in others and the world.

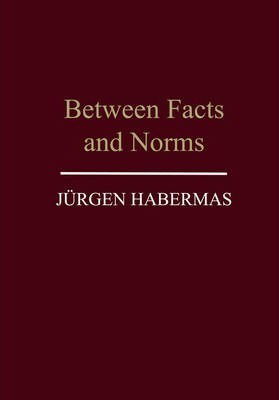

Habermas’s Between Facts and Norms, parts of which I read in manuscript during my grad school days, made me optimistic about democratic theory. There are many great works I could list in moral psychology.

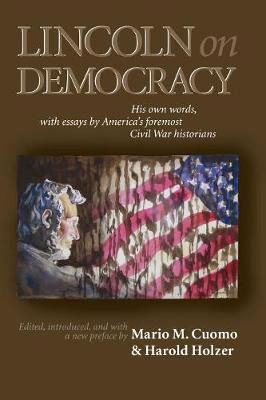

But to stay with political ethics, it might come as a surprise that my copy of Cuomo and Holzer’s Lincoln on Democracy selections of Lincoln’s speeches and letters is as well marked-up as my copy of Either/Or. Abraham Lincoln was a profound democratic theorist who anticipated the core of Habermas’s linkage idea. And his poignant pilgrim’s progress through personal hells, with a will strong as iron and a passion for justice that still leaves me awed and humbled, proved that nothing less than the “utopian dream” will do.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!