Brief Asides on Licorice by Bridget Penney

Licorice by Bridget Penney.

I’ve read this book twice now because it’s a strange and beautiful book tinged with all sorts of dark and possibly horrible things that kind of hovered along with me as I was reading it. It’s all set down in Sussex, on the South Downs which is just behind the coast where Brighton is. My sister lives somewhere on that coastline. For years as a child I went down to those parts with my family and so reading this brought back a whole flood of memories and things that I had buried deep ever since and which came back to me. But they didn’t come back straight and day-glo bright because this is a read that jump-started other influences too. So the book’s about an aborted film about a witch, and the blurb summarises what’s going on like this:

‘Chalk, gorse, old coppice, redundant dew ponds, a crossroads formed by the intersection of a B road and an ancient fisherman’s track. It’s August. The rain shows no sign of stopping. Licorice, a reclusive middle-aged filmmaker, has only a brief window of opportunity to realise her long-cherished film project about the story of Nan Kemp. A grisly story of infanticide, cannibalism and rough justice remembered on the map: local kids have dared and scared each other to run round ‘the witch’s grave’ since way back when. The rebuilt windmill provides a hypothetical link between the time from which Nan’s ‘story’ springs and the present.

For Angie, Licorice herself is something of a legend. Angie’s ex-lover Roy, sees Licorice as a bully and potential rival. Pete, co-directing the film, is consumed with unrequited lust for Angie... While Angie and Roy are definitively not speaking to each other, Pete and Licorice argue endlessly over how to shoot scenes and the direction the film is going to take. But Licorice has a secret only Pete knows. 25 Well-worn tropes lifted from films such as The Mask of Satan, The Blair Witch Project and Irma Vep give this narrative about failing to create a narrative its shape. The idea of folk horror intrigues Licorice.’

When I was growing up we had Peter Cushing, Vincent Price and Christopher Lee on late night BBC2 Saturday tv. It was mainly Hammer Horror and Poe and earlier classics like Whale’s Frankenstein. I used to stay up and watch them on my own and they were magical to me, eerie worlds of kind-of-sex and kind-of-horror that I found enchanting. I think because I watched them alone I thought of them as my own private treasures and have done ever since. I don’t think I was ever scared by them or turned on at all. It was more like they were intermediate fairy stories fit for an emerging isolated adolesecence lived out in a throng. It wasn’t a long stride to Angela Carter from there. I was already reading Poe, Lovecraft, Borges and Kafka in the same way. So all this slunk into my reading this book. These off-centre and haunting fairy tales coupled up with childhood memories of Saltdean, Brighton, Rodmell, Roedean, Hove and a myth and history saturated land and seascape. And windmills scattered all over taking me directly to the final climactic of the Whale Frankenstein where visual poetry and outsider ecstasy combine in an ordeal by fire. Windmills have always been symbols of shamanic flight whereby death and techniques of ecstacy open up a world to the underworld and cosmic zones. Their sails simplify and renovate conditions. Throughout I noticed that Penney details their dimensions and features so that I think the windmill becomes a kind of mythical image of death and the technique of necessary ecstasy which I had found in all those films and books years ago. And which of course still matter to me. So as you can see, I wasn't reading the book outside of myself . It recouped my past very personally. Here are some of the things I caught (only some, there are legion) that triggered all this:

'For a birth a wedding or in celebration of some great national event each idle mill would be positioned with one sweep approaching (that's to the left as you're looking at the mill) the perpendicular. About to almost touch the ground... Like giant semaphore. Broadcasting to quite a distance... if Nan and Thomas had never been taught their alphabet they wood have made sense of these messages... although the entry that powers the sweeps comes from the sky their touchstone the point of reference where humans read them as expressing meaning is the earth....'

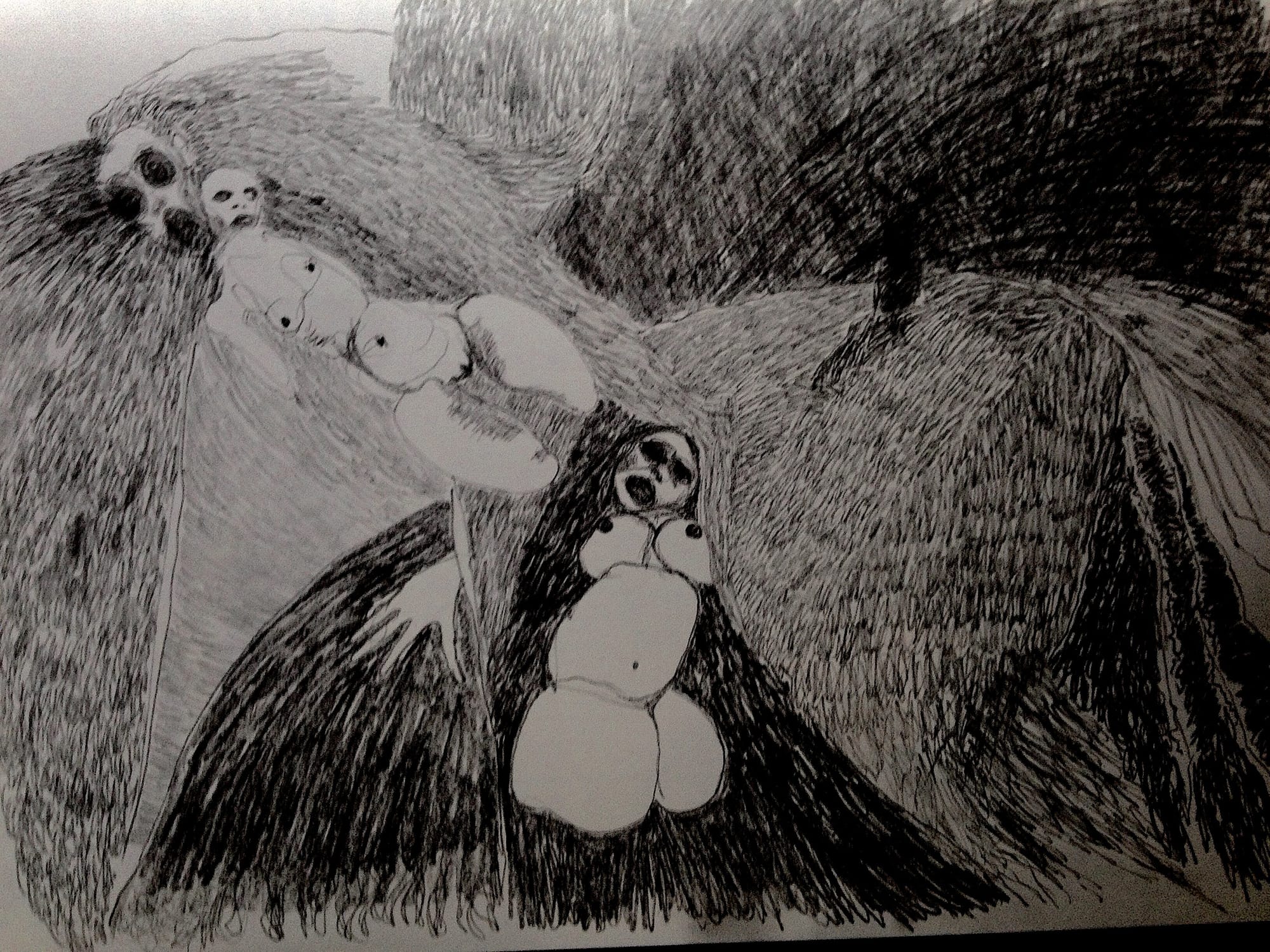

The magic nosedives to chthonic earthiness giving me a clue as to the sources of the witchcraft and magic which is all bundled up in the push of blood and semen, knots of wood and gorse, nature's nuclear glaring and the hairy, slobbery blindness of everything. Penney's book is full of chests and bellies, arms, legs, feet, eyes and the rubbish of the earth sniffing together an emptiness that seems to come from tearing off clothes and vanishings without goodbyes. The atmosphere is itself one of evaporation - brains, faces, mutations are all going without guess or God as Ted Hughes would say. The disappearing film is a lovely metaphor for this. It sheds its love and hangs like an empty husk on a briar so that each time characters get physical they fasten up and seem to be eating each other in a reworking of the horrifying trope that threads itself through it all like a strange dance.

'Words for them faded on the air hold your tongue or spew out your most random thoughts language is purely an interface with sensation no tender sweet nothings or ill-intentioned promises coming back to bite,' is how its put somewhere. Everything is weighted by its mauled, cannibalised and sexed historic seed. The book, the imagined film that guts itself as everything goes to hell, the gawping mouths, eyes, legs that increasingly seem more like grins through bones of teeth than uncrucified people, the flowers and bushes and trees that twin and hold their thoughts and decaying paraphernalia.

At first I wasn’t aware what was happening – the narrative is really rather brilliantly done – almost like a script it flows easily along, cutting and splicing with terrible simplicity so that I found I was two-thirds through in my first tentative sitting without looking up. I was very pleased by this – usually it takes me more time to get acclimatized to a book. And then I realized that what was happening was that I was reading everything with these two very personal streams running through – the holidays in Saltdean and the bungalow that backs onto the South Downs, and the Saturday night fairy tale horror films of my childhood. The mix was just a delight. The ingenuity of the plotting, the careful unfolding of the characters and the creepy embodiment of the place’s atmosphere all scumbled up so much that I had to read it twice to ensure that I didn’t lose sight of Penney’s story exhuming all these private resonances. What I really like is the way Penney manages to conjure up the places she writes. The historical detail isn’t clunked in from some geeky Google search but carefully unfolded alongside the sinews of a delicate web of storytelling. The result is that the two worlds – the present and the witchy past – fuse and speak to each other throughout. Which is what I love about the book – and about the place she writes. Sussex is one of those history soaked places – and not just a single history but many many histories. You can feel the past living in its presence and that’s the quality Penney has wonderfully evoked. Everything is alive and gapes into your brain down there. Nothing dies.

And that’s where the fearfulness starts to creep in. It’s all very well having this idea that history lives with us – but Penney is pointing to a very scary piece of history and a very scary character. There’s a great moment where we’re reading along and at this stage don’t know anything about what the film’s about (I never read blurbs before the book because I lose moments like this – hmm – so if you haven’t read the book yet maybe don’t read anything further here until you have or else you won’t get the full impact of the moment when you do get to it …) Anyway, we don’t really know anything about the witch character the film’s about and then Penney drops in out of nowhere this line:

‘ … as long as you don’t mind that you will inevitably be asked what it was like to get inside the skin of someone who killed her own kids and fed them to her husband.’

Well, this shook me right through. We already knew there was something rum going on, that she was a witch who had been hanged and so on - but that's pretty standard stuff – but this moment brought goose-pimples to the den and darkened the whole thing considerably for me. This is what I think Penney is doing. She’s waking up the English folk horror genre, edging it on with the right questions about gender politics that you really can’t avoid when you’re talking about hanging women for being witches but leaving you with something that remains once that particular issue has been exhausted, so to speak. I mean, wherever you stand on issues, doing this kind of thing is hauntingly terrifying because it goes further. It's a sort of ogre's cry to the wrong listener. It goes over the top of endurance and relief 'sweeling away like a torrent on a cliff.' So on top of the creepy sense that the landscape is alive, that ghosts haunt the living ancient bloody tracks, there is a kind of implacable evil too. I think the blurb’s right to reference the American horror The Blair Witch Project. Here was another film that I happened to see on my own at midnight. It was a Sunday in a cinema I walked a couple of miles to get to. It’s got the same inside out body atmosphere Penney's novel has, but without the old weird Americana of course. And the moment with the line about killing children and feeding them to the husband reminded me of the chilling moment in Lost Highway, the Lynch film, where Bill Pullman stands on his burbs porch in bright sunshine and asks: ‘ Who owns that fucking dog?’ (or something like that!) and the moment when the stranger standing in front of him answers the phone from another room. The chill is a combination of longing and a dislocated subconscious, all evil enemies and pineal gland swivel.

Taking us along that line, Penney begins to infuse every little thing with dread. She’s a writer within an unerring eye for detail so that everything's thingness becomes woven into this dread. It's what I learned from Dr Strange: magic is just advanced physics. I began to fear for the characters – not just for their sanity and definitely not for their relationships – but rather because of the indwelling amongst them of this nasty, basic, stone, flesh, vegetable existential threat. By the time you get to about page 40 you’re fully into this place. And Penney writes without letting anything of the hook. It’s not as if there’s this place and these people and this is what is happening to them. It’s more like this place and people are swallowed up in something so dark and evil that they’re going to disappear. It's as if they're charging chaotically into outer space. And when they do you know that nothing is good. I think there’s something about the English genre that makes the domestic a very fearful monster, where weaving and making things and made things generally are signs of dreadful powers beyond cephlapodic numbers. I like to think that this is the other side of English empiricism, an Englishness where a bluff confidence in hard stuff opposes fairy continental breezes, runs Brexit tropes, common sense, John Bull and white beef masculinity that likes to walk around naked. Its confidence lies in a visible physicality dredged out of gym-bully narcissism and inattentive ordure. I like to think of magic as what all this is afraid of and fighting off. And because of this, magic has no option but to kill her children and feed them to her husband. It's a humped, inpenetrable, half-illumined speechlessness.

Penney’s very good at the physical textures and the abrupt violent and layered catastrophes of sex. She sets up the characters as bodies colliding, bleeding and ejaculating over things, and the embodied passions and lusts harden and dismay as something else gets tangled in. She manages these lumping sprawls with the blood and snail trail ejeculata with finesse and tweezered realism. But always I'm thinking about the killed children and the food they became. This is an unholy communion and it gets smeared over everything and every body like a demonic slug trail. It’s as if Penney is showing us that the brute physical confidence is just a door. It’s all a way of shutting out the darker screams. You want to see real patriarchy? It’s just fear desperately trying to shut it’s eyes to alternatives. In such a place, Licorice is a transcient being. She comes from elsewhere, she’s going there too. But she’s also here. Like in the Lynch film, she’s both in this room and answering your call from your own home miles away. Just like this book seemed to be talking to me whilst I watched Frankenstein or ran around the Booth museum as a child.

The windmill - the book ends with the windmill of course - it's a kind of avatar carrying this message. It’s a remake, remodel but the place where Licorice’s obsession finds a last focus. I was so uneasy in those last pages. The drawings she posted reminded me of the pictures trauma children draw, hellish things like the ones done by the boy in The Ring film - another film I happened to end up watching alone. I just knew everything was wrong and couldn't be made right. But of course Penney turns you around and around constantly, as if you're on the windmill's sails, so that you can’t pin down the source of that unease. Which is what every great horror does. This is a particularly classy example. It doesn’t ever reveal itself in full. It doesn’t nail itself down . So it keeps itself alive right up to the very end and then further. It’s one of those disturbing tales that can be read again and again. There’s no final reveal that shares the code, so to speak. I loved it.

Of course, the relationships are hinges to the whole. They’re so very lively forces, utterly compellingly drawn and fluid and shimmery. I could actually think about them as people and I have to say the Licorice was someone I’d have wanted to meet and then run away from. She’s a haunting, powerful presence, a spooked up Jane Eyre done via Angela Carter, Joyce Carol Oats and Susan Hill’s little gem ‘Dolly’. Her imagination is what will devour you, is what I felt, and the whole occult world.

Of course it made me wonder about the state we’re in at the moment. Everything is closer to strange. Certain kinds of powers seem more obvious than before. And it goes deeper than just the political, social surfaces. Penney has written about the shadows rising, the evils that men have done and the haunted dread that crouches down in the corner every day just over there, in the corner of your field of vision, feeding children to their fathers. This is very unsettling, Bridget, unsettling like a field of nettles. But maybe that's because I'm not a woman. Maybe the underface of this is a liberating, creative, imaginative feminist power that blows the valves of my male discretions. Maybe the best way to grasp what's really going on is through the medieaval fragment that gets woven in:

'O Western Wind when wilt thou blow

The small rain down can rain

Christ! my love were in my arms

and I in my bed again.'

There's so much left to fathom. This is one of those classic dark pieces that will just slowly accumulate over time.