Glory, Beauty, Epiphany, Imagination: How To Do Moral Philosophy

Interview by Richard Marshall.

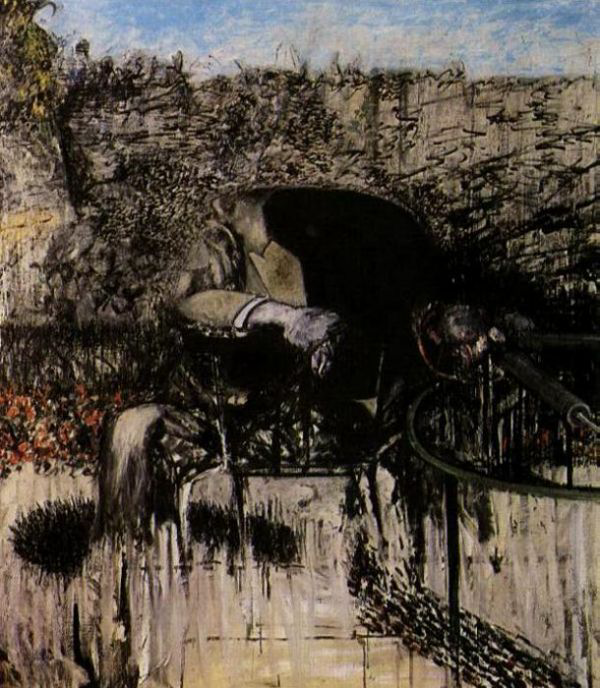

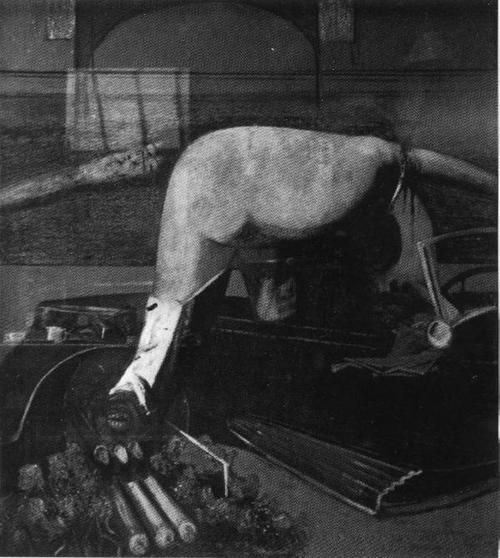

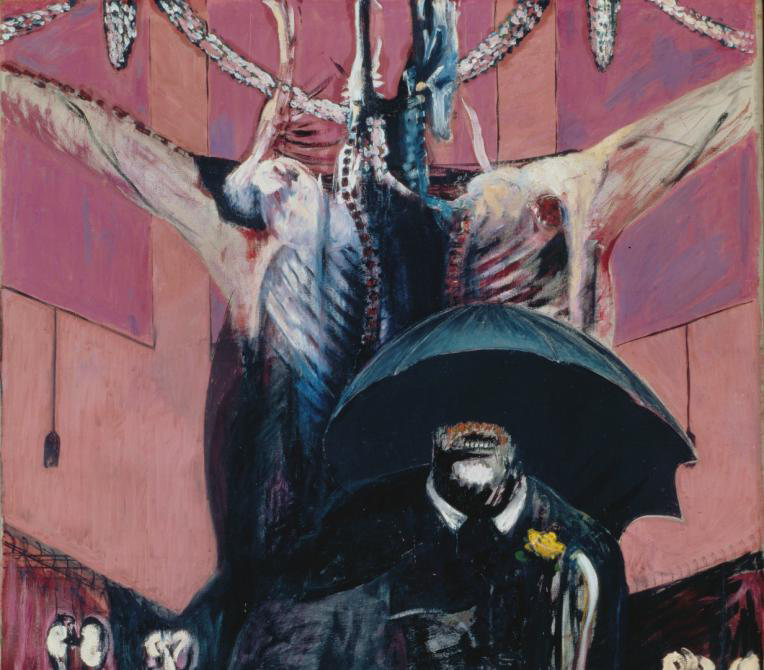

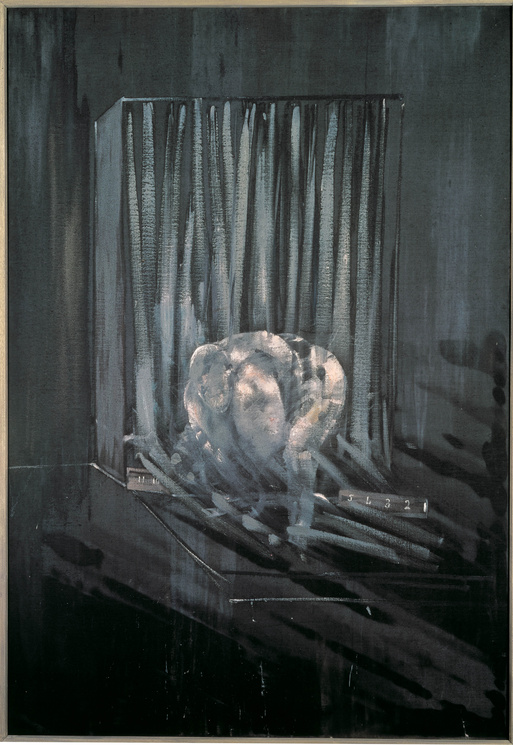

[Art: Francis Bacon]

'Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth. '

'One kind of applied philosophy that I find close to unreadable is the kind, usually consequentialist, that starts by telling us what our alternatives are—should we shoot this one Indian or those twenty?—and then challenges us to choose between just those two options, in line with some single tightly-described operationalised decision-procedure, and as if it was just given that there are precisely these options and no others. '

'The phenomenon that I call glory is, roughly speaking, what you get when someone scores a brilliant goal in front of a packed stadium. When I wrote “Glory as an ethical idea” it was because I was struck by the centrality of glory in this sense to our society. But though it is sociologically so central for us, it’s not even on the map for us philosophically.'

'So what about disagreement? I think we need to get away from thinking that there’s one thing, one single big phenomenon called ethical disagreement. Instead, let’s look at particular cases, and make an effort to understand the causes of disagreement from the other side; this too is, at least partly, an exercise in imaginative identification, in putting ourselves in other people’s shoes. On the other hand, very often the causes of ethical disagreement turn out to be philosophically quite uninteresting.'

'It’s not a “victory for women” when Julie Bindel or Germaine Greer goes out of her way to scornfully depict trans women as men who have had their bits chopped off. It’s not a “victory for trans women” when someone responds by telling Bindel or Greer that they’re no better than Nazis. Come on: they may not be very polite, but they’re not Nazis. This sort of invective is just disrespectful and unkind. And it’s music to the ears of the real Nazis, just as it is to the right-wing bigots and their fellow-travellers in the media. For them, to find such an easy way of getting the feminist left to fight itself is a dream come true.'

'As for my religious commitment, the question of how it affects, and should affect, my ethical thinking and writing is a standing question for me, and I suppose for any believer who’s also a philosopher. That commitment is always there, and always has been. And like everything else I really care about, it’s a matter of experience. I’d say that I know from experience that it’s possible to have epiphanies, and less exalted episodes too, in which you are made aware of something worth calling, however presumptuous it may sound, the presence of God. Now if you experience, or take yourself to experience, the presence of God, how should you represent that in your philosophy?'

Sophie Grace Chappell works in feminist philosophy, political philosophy, ancient philosophy, epistemology, philosophy of religion, metaethics, aesthetics, philosophy of literature, or on the philosophy of personal identity. Or indeed on various other things that happen to interest her. Her main current research project is, as usual for her, in ethics. With the support of a three-year Leverhulme Trust Major Research Fellowship (2017-2020, £142,000), she is just beginning a new book, provisionally entitled Epiphanies: an ethics and metaethics of experience. At least part of this will be about the relation between theory and experience in ethics, and in particular about the transformative power of what James Joyce, Gaston Bachelard, Emmanuel Levinas, and others have called “epiphanies”—flashes of insight or revelation that change the way we see the world, the way we understand ourselves, and the way we respond to other people. Iris Murdoch's hawk, in The Sovereignty of Good ,is one famous example of an epiphany; Louis Macneice's poem "Snow" captures another; when Wordsworth, in The Prelude XII.176 ff., talks about "spots of time/ that with distinct preeminence retain/ a renovating virtue", he is evidently talking about the same phenomenon. Here she discusses how to do and how not to do moral philosophy, why we should read more and write less, the moral imagination, seeing others as persons, glory, epiphany and beauty, contemplation, virtue ethics, the objectivity of ordinary life, the debate regarding trans identity, Bernard Williams and Christianity.

3:AM: What made you become a philosopher?

Sophie Grace Chappell: For a long time it wasn’t obvious to me, or anyone else, that I would become a philosopher. I didn’t actually know that that was going to happen till I was 27. I had some philosophical interests from a very early age indeed, in particular an obsession with Socrates and Heracleitus; from about 6 or 7 I devoured Lewis’ and Tolkien’s books, and read everything I could about their world-view. And once I sat down with an exercise book and tried to write down in it every truth there is about what exists, in a single systematising summary. Or perhaps I mean a Summa, because the next thing I knew I found a copy of Aquinas in the town library in Bolton, and I realised someone else had already done pretty much that, and the name for that game was “metaphysics”. At the time I was a bit miffed to be beaten to it. I was about 12.

But besides philosophy I had lots of other academic interests as well, in poetry and literature and opera and history and politics and languages for instance: I spent a lot of my childhood inventing fantasy languages and alphabets. And plenty of non-academic interests too: I’ve always been keen on mountains and various sorts of sport, and I was convinced for a long time that it was my Christian duty to spend my life in some kind of self-immolating service to others, in pastoral work or famine relief or spreading the good news or something. It’s a good job I didn’t try to. I am simply not a good enough person for that sort of work. I don’t have enough patience or kindness or self-denial, and I am too interested in other things besides people, such as books and ideas.

So in 1984 when I went to Oxford, I still didn’t know that I was going to be a philosopher, or even that I wanted to be. I knew I really liked Plato and the Presocratics, but I knew I liked Catullus and Vergil and Homer and Aeschylus and Thucydides too; and I often wondered about the whole business of academic essay-writing. It seemed so un-creative, and so second-order, to be constantly criticising other people’s ideas about other people’s ideas—and I really did want to be first-order creative.

A bad thing that happened to me at Oxford was this: I developed writer’s block, specifically in philosophy, indeed specifically (at first, anyway) with one tutor, Ralph Walker. Because he seemed to me the paradigm of what a philosopher should be, I didn’t want to present him with any work that was less than completely perfect. The result was that I made myself unable to present him with any work at all. Not unnaturally he assumed I was just lazy. The more punitive he got, the more fugitive I got. Overall I was very happy at Magdalen, but that bit wasn’t happy. Not at all. I don’t mean that it was anybody’s fault; perhaps not even my own.

So in Finals, to my deep sadness, I missed a First: the first time in my life I’d failed (as I then saw it) at anything academic. Even so, by the end of my degree in 1988 I was beginning to get the idea that putting together a large-scale argument might be a form of creativity, alongside writing poems, which is something I’ve always done. (If you think it’s hard to get philosophy published, just try poetry.) But I still didn’t know really whether the study I wanted to do was in theology or philosophy, because it was about free will.

After Finals I embarked on a PhD partly because I wasn’t sure what else to do with myself. I nearly jacked it in after a year. Because of the fiasco with my tutor, I was still suffering from low morale and writer’s block; also, independently of that, from the guilty feeling that I ought to be helping other people, not reading Augustine and trying to cope with my own apparently insoluble struggles to write a single sentence of my thesis without immediately crossing it out again. It seemed obvious that, since I didn’t have a First or an influential supervisor or doctoral funding, and wasn’t in a high-powered doctoral programme, and anyway wasn’t getting anywhere with my thesis, I would have no chance of getting a job.

My wife Claudia supported me through all this, both financially and emotionally, and we moved from the south coast of England, where I’d started the PhD, to Edinburgh, which we both loved straight away. Owing to computer troubles I lost everything I’d written in the whole of my first year. This was not a blessing in disguise, it was simply a blessing: it was wonderfully liberating not to have to try and salvage anything from that tortured shipwreck any more. And I got some funding, and I got a supervisor—the Irish Heideggerian theologian James Mackey—who tricked his way round my writer’s block. He kept directing me just to write these small exploratory pieces on tightly specific themes. And that was unambitious enough to be doable. So I wrote them, one after another, and then one day he put them all together in a row and said “There you go now: that’s half your thesis written.” I actually protested—“But you said those were only preparatory sketches! Surely they’re not good enough!” He brushed my words aside: “It’s not your life’s work. It’s only a bloody thesis. Just get the damn thing out.” And then it became possible to write again.

In 1991, after a year or two of the treadmill of long-shot job-applications, to my astonishment I got a JRFship at Wolfson College Oxford, and then in 1992 a college lecturership at Merton. It was really only when that happened that I finally felt reasonably confident that I was going to have an academic career in philosophy. Because then as now, the hardest academic jobs of all to get are the first one, and the second.

The happy ending is that I think I have ended up in a job where I do help people, and help them much more than I could have done, given my character, if I’d gone into a “caring profession”. Academia today doesn’t value teaching enough. But one of the great things about working for the Open University is that I’ve seen how teaching philosophy can make a huge difference to thousands of students’ lives. It gives them employability and qualifications, but that’s the least of it. The big things it gives them, or gives them back, are self-esteem and self-belief and curiosity and open eyes and minds. To me it’s a fundamental political imperative to have a form of society that doesn’t waste people. The society we’ve got now in the UK is horrendously wasteful of people’s lives and talents: so many of us just end up on the scrapheap. Even from the capitalist’s viewpoint that’s got to be inefficient. From any more humane viewpoint it’s just plain stupid, and desperately cruel too. It needs to change; to their credit the Scottish Government are trying to change it round here, though their powers and resources are currently constrained by the fact that Scotland is still, as I write, trapped in this unlovely union with Westminster. But in our society as it is, the double whammy is that when people are uninformed and uneducated they don’t argue or fight back or even vote; they’re too demoralised. Education is politically subversive, at least of bad orders: oppressive elitist kleptocratic governments like the UK’s have nothing to gain at all from having a well-educated population with open eyes and inquiring minds. As John Gielgud as Headmaster plaintively complains in Alan Bennett’s Forty Years On, “Why is it always the clever ones who are socialists?”

3:AM: One of the things you’ve written extensively about is how we should do moral philosophy – and how we shouldn’t! So can you lay out for us why you think moral philosophy – the theoretically rigorous type that is so familiar – and so dry – is the wrong way to do it – and this includes utilitarianism, Kantianism, contractualism, natural law theory and even virtue ethics, as well as systematic approaches to metaethics and moral psychology doesn’t it? What are the problems with systematic moral theorising?

SGC: I started writing a book in 2007 that was supposed to be an introduction to moral philosophy, following up on the general introduction to philosophy, especially epistemology, that I’d published in 2005, The Inescapable Self. My plan was to put the case for and against the usual menu of alternative moral theories, then end up in the final chapter advocating my own preferred moral theory, which at the time was roughly the liberal, non-doctrinaire natural-law theory that I’d argued for in 1998, in Understanding Human Goods. Then halfway through writing the new book I had a serious climbing accident on Zero Gully on Ben Nevis. In the light of that near-death experience, the competition of the theories that I was writing about in the book—it began to look to me a bit frivolous, a bit trivial, a bit of a philosopher’s parlour-game; compared with the real stuff of life, the hard realities of experience. That was why the book ended up called Ethics and Experience, and ended up not presenting my own pet moral theory, but my first shot at offering new arguments against the very idea of pet moral theories.

I don’t want to give unnecessary offence here to my many good friends and deeply respected colleagues who are moral theorists in the sense I tend to target. Of course you can be a deeply morally serious person and be a systematising moral theorist; no doubt it’s moral seriousness that makes most philosophers into systematisers in the first place. But it came to seem to me that there was a mismatch between that seriousness, and the theories that it was seriousness about. To be blunt, the theories didn’t deserve to be taken that seriously; the seriousness was admirable, its object not so much. As one of the epigraphs to Understanding Human Goods—so these things were already beginning to worry me in the 1990s—I’d quoted a wonderful line from Yeats’s notes on his own poem “The Dolls”: “I noticed once again how all thought among us had become ‘something other than human life’”. When utilitarians go on in a perfectly abstracted and seminar-room sort of way about whether or not to divert a runaway trolley by throwing a fat man underneath it, or about whether there is anything really wrong with murdering babies or buggering dogs except that it tends to upset people (or dogs), and when Kantians turn the question whether or not you should lie to the SS-man at your door about the Jews in your cellar into a kind of three-card-trick of practical rationality, and when natural law theorists get into solemn debates about whether cutting off a breeched baby’s head to save its mother’s life is a case of action or omission… then something other than human life, it seems to me, is what we’re getting, and I would just rather be talking about something else. Or if we do need to talk about these questions—and there may be times when we do, but too often we fail to ask first why we need to talk about them, what makes them into pressing issues for us—then I don’t want to talk about them in those ways.

3:AM: So why do you think an approach to moral philosophy via the notion of an ‘ethical outlook’ is a better way?

SGC: I didn’t put the point as well as I wanted to in the last chapter of Ethics and Experience. I spent the whole of Knowing What To Do trying to work out how to put it better. I’m still thinking about this now, while I’m writing Epiphanies. But the basic point has got to be something like this: Don’t start with a moral theory, start with where you actually are. Here is a question that I think ethicists should be asking alongside Nagel’s famous question about bats (at the moment I want to use it as the title of Epiphanies Chapter 4): “What is it like to be a human being?” So start with that. Start with what it’s like to be you, with your subjectivity here and now, with what looks serious and real and important and beautiful and (yes, why not?) fun to you just as you are, from your own viewpoint. Because actually that’s the only place you ever can start from, really, and one tendency of systematising theories is to obscure this truth. And when you end up ignoring aspects of your experience because they don’t fit your theory, then you’ve fallen into a kind of inauthenticity, a kind of Procrusteanism. If theory and experience don’t match then it is almost always theory that needs to give way. Not experience.

So it is about authenticity. One thing it’s not about is avoiding, or skimping on, rigour. On the contrary, ethical theory is studded with simple bad arguments, and anti-theory, at least the kind I want to do, is about avoiding them. For example there’s the idea that if you use any fragment of a given moral system, that must commit you to the whole damn thing. Far too many people who you’d have thought were much too bright for it still seem to think that, if I think some consequence matters deliberatively in some case, then that must commit me to thinking that nothing but consequences matter deliberatively in any case. So people who are anxious that they might get pushed into consequentialism refuse to think about consequences at all, ever. That’s an overreaction, and it’s based on a bit of bad logic. It’s just one example of how the patterns of thought that set up the systematising moral theories tend to be littered with quite basic mistakes.

This brings us to a third thing that I think is key to establishing and maintaining the hegemony of systematising theory, which is simply the sociology of academia. What would otherwise be inexplicably bad bits of reasoning, like the one I’ve just described, find and hold a place in academic thinking for structural reasons: because of the place in our wider society that academic philosophy has. (Or perhaps I should say the non-place: in The Tasks of Philosophy Alasdair MacIntyre has a wonderful essay about how every style of political ethics in academic philosophy is mirrored or imitated by something in social reality: mirrored by it, and blocked from social effectiveness by it.)

So in a modern university, Deans want there to be clearly-distinct subjects in their faculties; Heads of Department want there to be specialisations in their departments; in a kind of parody of what industry calls productivity, everyone wants everyone to publish. Notoriously, the result is that we all do publish, by the barrow-load, but our debates get more and more specialised, and they don’t head towards consensus. Recently I heard a very well-known philosopher argue that philosophy’s inability, after all these centuries, to converge on a theory of practical reasons gives us an inference to the best explanation that there are no practical reasons. It was a polished and pugnacious performance, but I was thinking “Come off it, Brian [for it was he]. The reason why we philosophers don’t converge is not that there are no practical reasons. The reason why we philosophers don’t converge is that we’re not supposedto converge; if we did, we’d be out of a job.”

Again, I don’t want to give unnecessary offence here. I’m not denying that there is lots of great work around on objectivity and practical reasons, some of it by people I know personally and admire very much. I am talking, a touch hyperbolically perhaps, about a tendency, one that worries me and has worried plenty of others: about a systemic pressure towards publishing whether we’ve got something to say or not, just in order to satisfy procedural and bureaucratic institutional imperatives—to get tenure or promotion or whatever.

3:AM: What do you think we should do instead?

SGC: We should write less and read more. For a philosopher, reading is the petrol in the tank: without it, you’re not going anywhere. In particular we should read the great philosophers more. We spend too much of our lives, even our academic lives, in a state of fragmented anxiety and hurry and rush and distraction, gabbling and babbling away to gain esteem and keep hold of the microphone: “hot, uneasy, snatching”, in Kipling’s wonderful phrase. I suspect the really good philosophy always happens as a result of deep, slow, careful reading. With reading there’s a space of still attentiveness that you can get into, and that you can teach others, in particular your students, to get into. That’s the happy place, the place to be. And that’s the place to write from. Maybe it’s what people mean when they talk about mindfulness, or alpha-waves. Or indeed theoria.

3:AM: You see the ‘moral imagination’ as being something that should be cultivated. What are we to make of your understanding of ‘moral imagination’ and why do you think it is so important? How does the moral imagination help us rethink the notion of what a reason is in making moral decisions and judgements?

SGC: Imagination is an untidy, bran-tub notion. If anything unites the various senses of the word, it’s probably something like “the vivid and affective grasp of possibilities”. It’s about the ability to envisage different things that could be, to reframe or redescribe the situation that you’re in and the potentials of that situation, in ways that make it clear to you that your options aren’t as limited as you thought or were told they were. So it’s about the ability to see solutions to practical dilemmas that other people have missed: in that sense it’s very closely connected with what Aristotle calls phronesis, practical wisdom. One kind of applied philosophy that I find close to unreadable is the kind, usually consequentialist, that starts by telling us what our alternatives are—should we shoot this one Indian or those twenty?—and then challenges us to choose between just those two options, in line with some single tightly-described operationalised decision-procedure, and as if it was just given that there are precisely these options and no others. As Williams observed of that very example, by the time you’ve framed the situation this way, all the important questions are already settled. The business of seeing the situation aright, so as to describe it aright, and so as to distinguish aright our alternatives for deliberation: all that comes before action, and before choice from an option-range too. So much moral philosophy doesn’t even talk about this business, but it’s here that much of the most crucial work of virtue is done. This is what I was on about in one of my articles I’m proudest of, though no one, alas, ever seems to reference it: “Option ranges”, in Journal of Applied Philosophy 2001.

In another sense, obviously connected, moral imagination is about putting yourself in someone else’s shoes. But I see that’s your next question.

3:AM: Yes… One thing you ask moral philosophers to do is to engage with the reality of other people, to see them as other people and indeed to rethink what it is to see anyone as a person. So what is it to see someone as a person and how should we rethink what this means in a helpful way?

SGC: Unless we’re neuro-atypical or abnormally socialised we will see others as persons; we just will, that’s bedrock for us, part of the background of the rest of our ethical thought. But perhaps because it is so basic to us, it hasn’t been easy for philosophers to articulate or develop explicitly an account of what it means to see someone else as a person. Part of the problem is that, though as I say we do just do this, it’s also something that we can do more or less well. Imaginative identification is instinctive at one level—but a moral achievement at another. And it’s absolutely central ethically speaking. Seeing the world from someone else’s point of view isn’t everything you need to be just and loving towards her. But it is one key thing. Good art is very good at this imaginative identification: good enough sometimes to make us feel uncomfortably close to identifying even with quite villainous people, like Macbeth or Shylock or Richard III. By contrast most moral theory doesn’t even try to do it.

3:AM: You’re interested in extending the moral theorist’s repertoire and ask them to consider glory and beauty in ethics – what do glory and beauty in ethics mean and why do you think they benefit ethical thinking? Is it your intention to help moral theorists to extend the expressibility of moral issues in ways that the conventional approach won’t allow?

SGC: The phenomenon that I call glory is, roughly speaking, what you get when someone scores a brilliant goal in front of a packed stadium. When I wrote “Glory as an ethical idea” it was because I was struck by the centrality of glory in this sense to our society. But though it is sociologically so central for us, it’s not even on the map for us philosophically. So I wanted to raise a number of questions about that mismatch. Why is there this mismatch, and where did it come from historically? Doesn’t it matter that moral philosophy misses glory out—doesn’t that tend to make our moral philosophy at least detached from how life actually is for us, and maybe unrealistic, narrow, puritanical, glum, earnest, humdrum as well? How could we get glory back onto the ethical map, and what changes might that lead to, elsewhere in the map? And: Didn’t the Greeks get something right here, that we’ve got wrong? Can’t we learn from them here? (By the Greeks I mean Plato and Aristotle, but also Homer and Heracleitus and Aeschylus and Sophocles and Pindar. Certain parts of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, such as Augustine and the Psalms, take glory seriously too. And perhaps Nietzsche counts as an honorary Greek.)

With “Kalou heneka” and “Duty, Booty, Beauty”, the two essays where I’ve taken further the idea that to kalon, the beautiful, might also be an intelligible reason for action for us, as it was for these antecedents in our ethical tradition, I’m raising the same sort of questions about another resource that I think can be got back into circulation in ethical philosophy. The idea is that these ethical resources are already there, perhaps inexplicitly, in ordinary people’s ethical thought. It’s philosophers who miss them, and fail to give an account of them that helps us towards a more humane collective self-understanding, which is presumably one of the main points of doing ethical philosophy at all.

Likewise with my work in progress on epiphanies, which is thematically connected both with glory and with beauty as ethical ideas, and also with an idea that is going to be crucial for us in the coming centuries (if we survive them), about the direct manifestation to us in epiphanies of the irreplaceable value of the world, of nature, and of the other species that we share the world with. If I can write philosophy that makes it more intelligible how and why “the environment”, the natural world, is not just material to be exploited and pillaged, but rather a place of epiphany, of beauty and wonder and even sacredness, then I will be delighted.

Behind these campaigns to get glory and beauty and epiphany back on the philosophical map, there’s the question what positive programme in ethics can be offered by an anti-theorist like me. If I want to overthrow the grand récit of ethical theory, then what do I want to put in its place? Part of the answer lies in Williams’ stinging retort to this question when his supervisor Hare put it to him: “I don’t want to put anything in its place—that’s not a place where anything should be.” But if we anti-theorists propose to change the landscape, we do have to explain what we think the landscape should be changed to. So another part of the answer to Hare is that there’s a whole variety of rich ethical resources that we can free ourselves up to deploy if we just get out of the grip of theory. And here (now I’m going well beyond anything that Williams says) are some of them: glory, beauty, epiphany, and indeed imagination.

3:AM: How does your approach link with a larger picture of the nature of knowledge rooted in both Aristotle and Plato? How is contemplation significant in this picture? Can you sketch for us how you see contemplation as being the focus of a good life and how it gets close to your own personal ethical outlook?

SGC: There’s a big theme that I get from Aristotle on theoria, and Plato on the vision of the good, and Murdoch and Weil on the notion of attention, and Wordsworth and Keats and Eliot on moments of clarity and vision and stillness, and Blake on the doors of perception, and Gerard Manley Hopkins on inscape, and lots of Christian writers both ancient and modern on the idea of contemplation or something like it. Richard Foster’s Lent book Celebration of Discipline, for example, has a wonderful chapter on the discipline of study. The theme is that of attending to the object in itself—a tree or a kestrel or a mountain or a work of art, or in Murdoch’s example, the Russian language—as what it is quite apart from my desires or wishes, as something that discloses itself to me, and thereby imposes on me a certain kind of discipline, a set of norms or demands that I have to respond to. I was trying to talk about this already in the last chapter of The Inescapable Self, where I wanted to suggest that this kind of “loving truthful attention” as Murdoch calls it might in some way be an answer to classic epistemological scepticism. Not a straight answer, obviously—not something of the form “Cartesian scepticism is wrong because dot dot dot”—but an answer that enables us to exorcise the kind of dislocated anxiety or dissociating urge that leads us to raise sceptical questions in the first place. The kind of real contact with the world that the Cartesian sceptic longs for is perfectly possible; but it’s more like an ethical achievement than a logical one. And in a way, the contact is contemplative. Maybe, in fact, that’s what Descartes himself was getting at, by bringing God and trust in God as a non-deceiver so centrally into his argument. If so, then most of our typical first-year lecturing on the Meditationsthese days will have missed his point completely.

So I have this picture of epistemology—and this picture is already somewhere in the background in the other book I wrote about knowledge in 2004-5, Reading Plato’s Theaetetus. There is the focal case of knowledge, objectual knowledge, knowledge of things as they are in themselves, and the other kinds of knowledge—knowledge-that, knowledge-how, knowledge-what-it’s-like—are spinoffs or derivatives of this case. And then there’s the following structural analogy. Practical rationality, the ability to see what things are means to what ends, is spectrum-related to practical wisdom, expertise and virtue in picking out both means and ends: practical wisdom is the ideal limit of practical rationality. Just likewise objectual knowledge, awareness of things as they are, is spectrum-related to contemplation, intent and perceptive awareness of things as they are: theoriais the ideal limit of objectual knowledge. So with both practical rationality and objectual knowledge, there is or can be a movement towards this ideal limit. And in each case, such movement is expressive of a key virtue.

3:AM: Why do you think there is at least one correct list of the virtues?

SGC: Because I’m an objectivist.

3:AM: And does this mean you’re a virtue ethicist?

SGC: Yes and no. I think ethics should be about the virtues, certainly, however we list them. And the point of any lists that people may offer can vary: provided the lists divide the same ethical terrain, the terrain roughly of human excellence, it’s not a big problem for the objectivist if they divide it differently. But alongside virtues, there are lots of other things that ethics should also be about. As you might by now be expecting me to say, I don’t think there’s much mileage in trying to build a single theory ground-up on the foundation of the single explanatory notion of virtue; in philosophy as elsewhere, good explanations are always richer than that, and untidier too. As you may also be expecting me to say, I think it’s a mistake to move from the premiss “The virtues play some important explanatory roles in ethics” to the conclusion “Nothing but the virtues ever plays any important explanatory role in ethics”. The premiss is true, but the conclusion is false. And I’d say, obviously false.

3:AM: What makes you argue for the objectivity of ordinary life, that a “thicker”, more value-laden, understanding of our perceptions of the world can be therapeutic against a thin perception of a non-evaluative world? Is Wittgensteinian thinking important to you in this – and isn’t there evidence that there’s not enough agreement in the ethical domain to justify an objective view of values, which undermines this ‘thick view’ approach?

SGC: I’m a Wittgensteinian all right. But not a scene Wittgensteinian. He is always worth reading, and he asks some wonderfully illuminating questions; some of his answers are good, too. He’s not right about everything or even nearly everything, and I don’t want to be part of the philosophical enterprise of pretending that he is—any more than I want to pretend he’s wrong about everything. But, yes, the later Wittgenstein is one of my key reference-points.

What makes me argue that way? Well, thinking it’s true, of course. Less flippantly, it connects with my general suspicion of abstraction and the denial or sidelining of our actual experience of life. There’s a tendency in analytic philosophy, deriving from the usual suspects in the “disenchanting” enlightenment, Bacon Hobbes Newton Hume La Mettrie Bentham Mach etc., to think that experience could not possibly be, in its most basic form, experience of value. I think that’s just untrue, and demonstrably untrue by looking more carefully at what is actually there in experience.

So what about disagreement? I think we need to get away from thinking that there’s one thing, one single big phenomenon called ethical disagreement. Instead, let’s look at particular cases, and make an effort to understand the causes of disagreement from the other side; this too is, at least partly, an exercise in imaginative identification, in putting ourselves in other people’s shoes. On the other hand, very often the causes of ethical disagreement turn out to be philosophically quite uninteresting. For example, there isn’t a good argument for the oppression of women. There simply isn’t. If you doubt me, just try finding one. There’s an extremely large literature of arguments in favour of the subjugation of women, and even the best bits of it, such as those written by my old friend and colleague J.R.Lucas, are essentially nonsense.

So there is no philosophical interest, or at least no first-order interest, in looking at the arguments. I don’t mean philosophers shouldn’t look at them, and counter them philosophically and politically—of course we should, where necessary. But doing that won’t be very intellectually stimulating or exciting, because the arguments for misogyny or subjugation are just silly, and/or driven by quite blatant structures of power and vested interest, and/or dependent on obvious falsehoods, or on ways of reading some tradition or sacred text that are themselves either silly or ideological or both. With ethical disagreement, I think this sort of thing happens a lot, and that it’s a bit naïve to think that you’re usuallyup against someone whose case for misogyny or homophobia or racism or chattel slavery or whatever is just as good and offered just as much in good faith as your case against. There are some peer disagreements, sure, or at least some disagreements between rough peers. But they’re much more the exception than the rule, and where they happen, the best response is usually not sceptical boggling. It’s to talk some more, and get a better understanding of our differences.

3:AM:The issues regarding trans identity continue to be rather toxic. You’ve engaged in this debate however. What do you think are the salient issues in this debate, and where do you stand in particular on the disagreements between trans people and feminists on this issue? Why do you think the issue has become so toxic?

SGC: As I have to keep saying, it’s a pity to talk of “trans people and feminists” as if they were discrete groups. A lot of us are both. Nor is it impossible to be a trans woman who is gender-critical. Labels are so often just a nuisance.

Here too, we shouldn’t treat this conflict as if it was just caused by abstract theories. Here too, a lot of the bad stuff that goes on arises not from theory but from experience. Thus I think a lot of the very visible toxicity comes simply from pain, and from the sense that “the other side”—if we have to talk of sides—are not acknowledging that pain. A lot of people “on the gender-critical feminist side” (the GCFs, for brevity) have either undergone something traumatic that made them GCFs in the first place, or are rightly angry on behalf of someone else’s pain. Meanwhile for every trans person, including me, there’s a very simple and obvious cause of pain in the unavoidable fact of not having been born the shape you would have liked to be. You can get past that, to some extent, by learning to live as a woman (or a man) even though you weren’t born as one and perhaps still aren’t shaped like one. But then as a trans woman you want to be acknowledged as a woman socially, and a lot of the pain you’re likely to feel comes when this acknowledgement is withheld or denied. Rather as an adoptive parent would be pained by having people shouting in her face “You’re not a REAL parent, because SCIENCE”. (I’ve had analogous shouters in my own face, sadly enough.)

So there’s pain and anger on both sides, and too many people talk in a way that stokes it. Quite unnecessarily. And massively counter-productively. It’s not a “victory for women” when Julie Bindel or Germaine Greer goes out of her way to scornfully depict trans women as men who have had their bits chopped off. It’s not a “victory for trans women” when someone responds by telling Bindel or Greer that they’re no better than Nazis. Come on: they may not be very polite, but they’re not Nazis.This sort of invective is just disrespectful and unkind. And it’s music to the ears of the real Nazis, just as it is to the right-wing bigots and their fellow-travellers in the media. For them, to find such an easy way of getting the feminist left to fight itself is a dream come true.

On the substantive issues, the most basic question is probably just taxonomical. Are trans women women or aren’t they? Here too the urge to over-simplify gets us into trouble. We imagine we have to line up in two discrete sides, behind an unqualified Yes and an unqualified No. I don’t think that’s right at all. Here as in so many other places, the right answer is more like “In some ways yes, in other ways no”. But group-think and party-lines—and the yearning to systematise and tidy things up—make it hard for us to say that.

And then to compound things, some GCFs seem to mix up a generic claim with a universal quantification. They want to say that “Men oppress women”—in general, for the most part—but treat that as if it meant the same as “Every man oppresses every woman”—without exceptions. Then because they think that trans women are men really, they identify every single trans woman as part of the oppressor class, as part of what they’re fighting against, and so as not a possible ally. A better way of thinking about it, it seems to me, is to take the generic route: men as a class oppress women as a class. But whether or not we say trans women are men (or males), that is not a universally-quantified statement about every individual man without exception; it is a generalisation that says what is true for the most part. So it’s really a claim about an ideology, patriarchy. And that ideology, if you ask me, is everybody’s enemy. Whether we’re GCFs or trans women—or both—we all have an interest in ending it. Even men have an interest in ending it; because patriarchy oppresses them too.

3:AM: Can you suggest ways of improving the situation for the future?

SGC:Play nicely.

3:AM: Two influences I haven’t mentioned feeding your thinking are Bernard Williams and Christianity. It’s an unusual combination. What do you find so helpful in these two sources of your moral thinking? In particular, how important to your thinking is it that you are religious?

SGC: I’ve written a lot about Bernard Williams and I get a lot from reading him, but there’s also plenty I disagree with him about. Contrary perhaps to appearances, the appearance for instance that I quote him all the time, I’m not a Williams groupie. If I’m an anybody groupie that would be Alasdair MacIntyre. But there are more epigrams in Williams.

MacIntyre and Williams have much in common. They both do philosophy by thinking in admirably scholarly and detailed ways about its history, they both reject standard-issue contemporary academic moral theory (and both reject it at least partly on the grounds of a sociological critique), they are both deeply interested both in Aristotle and also in Nietzsche, they are both looking for new spaces for new thinking about new possibilities in ethics. I’m with them both on all of that, and probably closer to Williams in being, like him, temperamentally more of a Platonist than an Aristotelian. But in two ways at least they emphatically differ. MacIntyre’s an idealistic revolutionary socialist, Williams is a cautious social democrat; MacIntyre’s a liberal-but-also-traditionalist Catholic, Williams is an uncomprehending, shoulder-shrugging, and (to my mind) rather glib atheist. On both the political and the religious contrasts, I’m with MacIntyre and not with Williams.

As for my religious commitment, the question of how it affects, and should affect, my ethical thinking and writing is a standing question for me, and I suppose for any believer who’s also a philosopher. That commitment is always there, and always has been. And like everything else I really care about, it’s a matter of experience. I’d say that I know from experience that it’s possible to have epiphanies, and less exalted episodes too, in which you are made aware of something worth calling, however presumptuous it may sound, the presence of God. Now if you experience, or take yourself to experience, the presence of God, how should you represent that in your philosophy? I don’t think that’s a straightforward question at all. Many ways of doing philosophy of religion seem to me hopelessly incongruous because of just this mismatch, the mismatch between what they’re about and the way they talk about it, or try to. They remind me of Forster’s phrase in A Passage to India about “poor little talkative Christianity”; also of Williams’ remark in Philosophy as a Humanistic Discipline (p.206) that “of much philosophy purportedly about [these] subjects… one may reasonably ask: What if someone speaking to me actually sounded like that?”

I’m inclined to think that the question of tone or style, and of how that tone should relate to its content, when the content is philosophical thinking about God, is essentially a poetic one, in the broad sense of “poetic”. I don’t at all mean by this to signal any kind of irrealism about God—on the contrary. But I do mean that managing to write well about God, if anyone ever does manage that (perhaps Aquinas and Augustine do sometimes; and George Herbert and John Donne and Gerard Manley Hopkins and T.S.Eliot; and the psalmist and the gospel-writers), is among other things a kind of artistic or aesthetic achievement. And a difficult one; it’s not for nothing that we can sometimes get writer’s block; sometimes it’s maybe even better to have writer’s block about God than to write a phortikos epainos, to write something thoroughly crass and tin-eared about him. “Whereof we cannot speak” and all that jazz.

And this carries over from philosophy of religion to moral philosophy. Because I’d say just the same is true about writing about ethics. Williams again (Morality(Cambridge: CUP, 1972), p.11): “In the deepest sense of ‘style’, to discover the right style is to discover what you are really trying to do.”

3:AM: Finally, are there five books you could recommend to the readers here at 3;AM that would take us further into your philosophical world?

SGC: Should people be interested in my philosophical world? I don’t know. There is a philosophical world—just the one of it—and in my own wayward fashion I hope to contribute to that.

I’m a little suspicious of lists, too, so let me subvert the idea of a single list of five by providing more than one list of more than five items.

So first, since the question is at least initially about me. Edited collections and teaching texts aside, the books I’ve written—and in different ways I’m still quite proud of all of them—are these:

- Aristotle and Augustine on Freedom. Macmillan, 1995.

- Understanding Human Goods: a theory of ethics. Edinburgh University Press, 1998. Oh that subtitle.

- Reading Plato’s Theaetetus. Academia Verlag/ Hackett, 2004.

- The Inescapable Self: an introduction to Western philosophy since Descartes.Orion Books, 2005.

- Ethics and Experience: ethics beyond moral theory. Acumen, 2009.

- Knowing What To Do:vision, value, and Platonism in ethics. OUP, 2014.

If you asked me which are the eleven texts from the history of philosophy from which I’ve learned most, I might answer like this. (It isn’t a ranking, nor are any of these lists; in this kind of case ranking seems to me an entirely empty exercise.)

- Diels and Kranz, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker

- Plato, Protagoras

- Plato, Symposium

- Plato, Theaetetus

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

- Augustine, Confessions

- Aquinas, Summa Theologiae

- John Locke, Essay concerning Human Understanding

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

- Immanuel Kant, Groundwork

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty.

Or if, again, you asked me which are the nine books from twentieth-century or later philosophy from which I’ve got most, this might be my reply:

- William James, Principles of Pyschology (stretching the century slightly)

- Bertrand Russell, Lectures in Logical Atomism

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

- Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity

- David Wiggins, Sameness and Substance

- Simone Weil, Cahiers

- Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue

- Iris Murdoch, Existentialists and Mystics

- Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy.

And if, finally, you asked me which are the twenty-four non-philosophical books from which I’ve learned most and which have done most to form my own ethical outlook, I could answer like this:

- The Bible, and specifically the Gospels and the Psalms

- R.R.Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

- Ursula Le Guin, Earthsea

- Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (almost the first book I ever read, along with Peter Rabbit)

- Shakespeare

- Homer, The Iliad

- Tolstoy, War and Peace

- Aeschylus, The Oresteia

- Catullus

- John Keats

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- William Blake

- S.Eliot

- Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

- William Wordsworth, The Prelude

- Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution

- Hilaire Belloc, The French Revolution

- Charles Dickens, Bleak House

- George Eliot, Middlemarch

- B.Yeats

- Rudyard Kipling, Kim

- Eric Newby, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush

- Richard Foster, Celebration of Discipline

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, A Time To Keep Silence.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End TimesSeries: the first 302