Hans Falla and Janine Paulette in conversation about Steve Finbow’s ‘The Mindshaft’

.

.

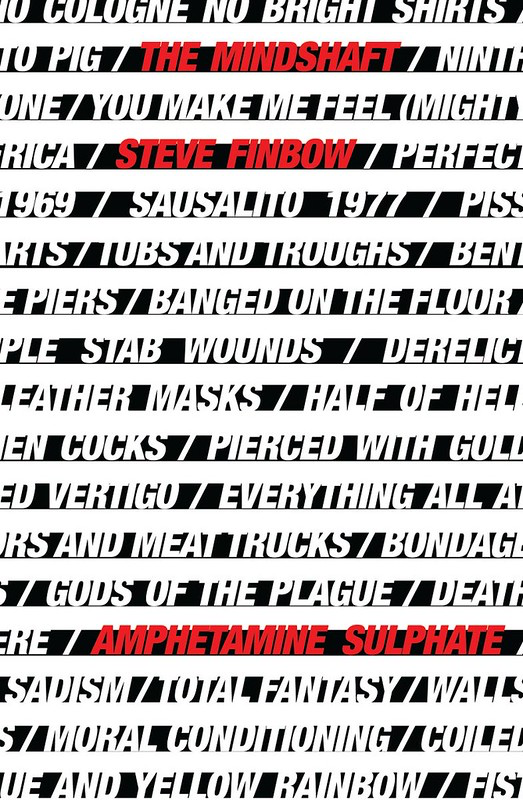

Steve Finbow’s The Mindshaft (Amphetamine Sulphate, 2020).

Hans Falla and Janine Paulette originally planned to meet to discuss the new novel by Steve Finbow face to face. Alas, Covid 19 prevented that and so they met on Zoom and transcribed their conversation for 3:16.

Hans Falla: The 70s has only one face: that of a violent contradiction. It went astray, was destroyed, was extremely private, distant, passionate, turbulent and filthy. Nothing is more necessary or stronger in us than this time. It was the beginning of a kind of cannibalism. It was a time that didn't want your love unless you knew it was repulsive, and love would neverbe what would survive it. It was in harmony with its annihilation. It never seemed decent because its indecent people had moral eyes and feared lewdness. They wanted to be frightened by the crowing of a rooster or when strolling under a starry heaven and savored the "pleasures of the flesh" only on condition that it wasn’t insipid. But in the 70s, all "pleasures of the flesh" were insipid, even those classified as "dirty." The usual debauchery dirtied debauchery itself, while, in some way or other, anything sublime and perfectly pure was left intact. The 70s debauchery soils not only body and thoughts, but also the vast starry universe serving as a backdrop.

Janine Paulette: It’s a time when you noticed how much extreme seductiveness crosses the boundary of horror. The seducing act was in time what Ballard’s window curtain was in space.The 70s had a knowledge that enslaved, with a servility wherein each moment has meaning only in relation to all the others that followed it. Everyone back then was irritated because he didn’t know why he wasn’t one of the others.This despair resulted in neither weakness nor dreams, but in violence. It became only a matter of knowing how to give vent ; whether to wander like madmen around prisons, or whether you were going to overturn them.

HF: I think human existence requires instability, the impermanence of things. The result is an ambivalence with respect to all great and violent expenditure of strength; such an expenditure, whether in nature or in man, represents the strongest possible threat because you’re going to get tired and stop moving. The feelings of ecstasy are best admired from afar. The 70s was all about that kind of prudent concern. It was all about an anti-radiance, a gigantic loss of heat and light, flame, explosion; but remote from men, who needed to enjoy in safety and quiet the fruits of their own cataclysm. To this era belongs the solidity which sustains houses of stone and the steps of men,at least on its surface, for buried within the depths is a kind of drab incandescence, and that’s what Finbow gets to really brilliantly.

JP: Sure, there is always some limit which the individual accepts. Finbow identifies this limit as his novel itself I think. Horror seizes him at the thought that this limit may cease to be. But he also wants to say we are wrong to take this limit and the individual’s acceptance of it seriously. The limit is only there to be overreached, is what he’s getting to, and that’s the reason he’s written it in the first place. Fear and horror are not the real and final reaction; on the contrary, they are a temptation to overstep the bounds and of course Finbow knows this and makes it perfectly clear that he is where we are, which is not even ‘not there’.This world then is purely parodic, that each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form.It’s like all this stuff about desire reduces us to pulp, the Mindshaft and all the walk on, walk off parts, like he’s collecting body parts you know?

HF: Absolutly. I enjoyed the innocence of unhappiness and of helplessness that attracted everyone, which flooded through with pleasure precisely to the extent it brought them to despair, with the Son of Sam thing , this power of death motif that’s about how this real world can only have a neutral image of life, that life's intimacy does not reveal it's dazzling consumption until the moment it gives out. And of course, for ‘life’ here read ‘the novel’.

JP: Exactly, so the whole book is a sort of rupture-in anguish-leaving us at the limit of tears: in such a case we lose ourselves, we forget ourselves and communicate with an elusive beyond where pleasure squanders resources to no purpose, like a wound bleeding away inside us. It’s like the whole thing, all the culture of that time, it’s about making sure of the uselessness or the ruinousness of its dingy extravagance. It's the reason Mean Streets is the great move from that time. For me anyway. It was that idea, ruinous dingy extravagance that I think that film got. And Finbow's got it here too. Anyone who lived in the 70s knows what he's going on about I think.

HF: Finbow’s always good at this idea of eroticism at the brink of the abyss, of leaning out over deranged horror to where the abyss is the ruin of the ruin. He takes us to the edge of the same abyss by suppressing laughter and ecstasy and leaves us wondering just what "questioning" of everything looks like, or if it’s even a thing. It’s a stage of anti-rupture, of not letting go of things, of not looking forward to death. Kind of anti-Bataille in this respect I think.

JP: What he uses de Sade for is interesting. As if for him de Sade is trying to bring to the surface of the conscious mind the things that revolted that mind in the first place, as if the chaos of the mind constitutes a reply to the providence of the universe. So I read it as if his – Finbow’s - seventies represents an awakening in the night, where all that S/M is just anguished prose, prose that goes somewhere and knows something that was already there but somehow was locked inside and needed releasing. It’s a prose that stays away from evil knowing that it can’t entirely do that, for the words, the images (once dissolved) are charged with everything the words have already experienced, and attached to objects which link them. The sixties, governed by ingenuousness and innocence, is thus regained in the horror of atonement, which is Finbows’ America and his seventies. The purity of love is regained in its intimate truth which is that of violent death. Violence and the instant of divine intoxication merge when they both oppose those intentions from before based on rational calculation.

HF: Yes, that’s interesting isn’t it, the way everyone is pretty calculating here? Happenings aren’t just chances are they, it’s all pretty organised and oddly bureacratised despite everything. From Warhol to Mapplethorpe everyone seems to be running against the instant and the instantaneous. They all seem pretty regimenting and on a calculated quest for survival, even in the death and erotic teritory. And it’s not just that, but it’s also a well oiled dependency culture too. These guys seem to live their time as new individuals by being dependent on the death of other beings. You get the sense of a sort of calculation being enacted: ‘Had they not died there would have been no room for new ones.’ Reproduction and death condition this immortal renewal of life; they condition the instant which is always new. But it’s totally controlled and I think that’s why Finbow resists giving any of them a tragic view of the enchantment of life, and is also why tragedy is the symbol of their enchantment – and why it’s about that and not disenchantment.

JP: Yes, that’s where the book takes its biggest risk I think, placing Mapplethorpe in cahoots with the Son Of Sam and running them together and seeing what happens – I guess only literature could reveal this process - without which the deaths would have no end – and happening, or presented as happening as a way of necessity, of creating order. I always find even the thought of snuff movies uncomfortable to be honest though.

HF: So you think Finbow is playing with this idea of life always taking place in a tumult, without apparent cohesion, you know, it always looks so messy right, but it only finds its grandeur and its reality in ecstasy and in ecstatic love that has rules, you know, things like dress codes and signs?

JP: He’s pressing on us a code book of sacrifice and I think he’s saying that that’s what a novelist is doing all the time, or at least, the kind of writers he reveres – the guys he name calls on the tram at the start and finish – Kafka, Walser, the usual crowd – and not just writers of course but that whole milieu – he’s about ordering and setting out codes for nothing other than the production of sacred things. His novel is like being fully absorbed in the sight of the corpse. The horror and despair at so much flesh, nauseating in part, and in part very beautiful, all done in words that aren’t his, or weren’t until he started to order them in a process that’s kind of a violence of overcoming, a disorder of laughter and sobbing, writing them against the excess of raptures that they’re about, that’s what I take from the book at a profound level. Finbow seizes on the similarity between a horror and a voluptuousness that goes beyond it, between the ultimate pain and the unbearable joy of being a writer.

HF: I’d like to add to that and stress that in this work flights of artistic experience and bursts of erotic impulses are seen to be part and parcel of the same movement. They are the substances which we bury ourselves in in order not to see. I think Finbow is worrying about what is being formed by the words, their labyrinths, the exhausting immensity of their possibilities, and pointing to their treachery, of them having something of quicksand about them.

I think his novel is more like a prayer book than a book of entertainment. The accomplished technique behind them is that of the modern artist, maybe the philosopher even, who sets his signs out in daylight before their own divine mysteries. I think we have to read it as they were written, with the intention of fathoming a mystery which is no less profound, nor perhaps less ‘divine’, than that of reading Proust, say. Reading Finbow asks for betrayal at the same time, through reading and critical reflexes demanding indecency and the equivalent of criminal debauchery. He writes books distinct from juridical existence, as if he wants to contradict the idea that human life cannot in any way be limited to the closed systems assigned to it by reasonable conceptions. Every immense recklessness, discharge, and upheaval that constitutes each moment in the book could be expressed by stating that each starts with the abundance of these systems; so it allows in the way of order and reserve meaning from the moment when the ordered and reserved forces liberate and lose themselves for ends that can always be subordinated to any thing one can account for. It is only by such subordination—even if it is impoverished as no doubt it has to be —that the human becomes isolated in the unconditional splendor of material things.

JP: I agree. I’d put it like this, tentatively of course. His novel reveals the process of the law – a law without end –independently of the necessity to create order. The book assumes the task of regulating collective necessity and, like the absolute upholding of moral laws, is dangerous. It leads to the same place as all forms of eroticism — to the blending and fusion of identical, unified objects. It leads us to time, away from death, and away from continuity. It is a way of escaping its own weight by refusing to laugh. It refuses translations into laughter, and might even be a new form of the novel – the straight-faced! Which of course is hilarious.

HF: As every personal hallucination always is. And can’t be for anyone else of course. The lack of any emotional element gives it an obsessive value.

JP: He’s written out a narcotic, if you like, revealing both itself and an unbreathable void. Each of its movements begins with a singular experiencewhere anguish and ecstasy coexist which ceaselessly kills and is ceaselessly killed by our usual boredoms. Finbow’s novel gives rise to cataclysms which demanded necessity as a law above themselves. His novel is free to resemble everything that is exactly itself. It can set aside the thought that it is what keeps the rest of things from being absurd. To put it more precisely, since language is by definition the way silence is made visible, just as archtecture is the way we make space visible, violence is loud. It was something outside language because silence can do away with the things that language states.

HF: It’s as if Finbow is writing about those who never want to differ from themselves. It’s a new perspective I think for the modern artist to take like refusing to be virile in the light of our modernity, our perfect incomprehension of the sun.

JP: He pits the lure of the will against the obstinacy of an impotent void, and wonders why we squander our resources to no purpose, just to be sure of the uselessness or the ruinousness of our extravagance. He wants us to feel as remote as we can. He’s writing a kind of treason, about people who see other people as limits and the beginning of a cycle of servitude. In this respect I think he is actually in line with de Sade’s system, which takes itself to be the ruinous form, of eroticism, of living, and perhaps of art. But he doesn’t agree that it’s ruinous. It just shows what spending really looks like. Just like an immense industrial network cannot be managed in the same way that one changes a condom, so too Finbow shows how what we need to grasp is beyond an individual act but rather how any act expresses the circuit of cosmic energy on which it depends, which it cannot limit, and whose laws it cannot ignore without consequences. I think that’s what his novel’s really about.

HF: Yes, I like that. It’s why his realism gives me the impression of veracity. It’s a realism that is built, I think, on his being aware that the sacred quality hidden in the experience of eroticism is something impossible for language to reach, as if an obscenity so great that I could vomit the most dreadful words still wouldn’t be enough! I think that’s why the Son of Sam material is so well handled, and the whole thing is a development of lucid thinking. The apparent changingness is deceptive: and whatever he’s doing requires a loyalty and complicity, which feels very intense as you’re reading. I felt that anyway.’

JP: Absolutely. I think that’s right: the immediate impression of lone rebellion may obscure that. I guess the desire is for fundamental communication with the reader who nevertheless can't believe the extreme limit has been attained, and who never remains there anyway for if there subsisted a satisfaction, as small as I can imagine it to be, it would distance me from that supposed extreme. Readers, like writers, incite themselves to go there, and cannot make a distinction between themselves and those they want to communicate with. Finbow rubs our faces in this, because for him that’s the immense, ludicrous, and painful convulsion of all of humanity.

About Steve Finbow

Steve Finbow’s non-fiction includes Allen Ginsberg: A Biography, Grave Desire: A Cultural History of Necrophilia, Notes from the Sick Room, Death Mort Todand The Mindshaft. He is currently working on a book about Francis Bacon and editing the Infinity Land Press Anthology.