Indifference, Cambridge Pragmatists and Companions in Guilt

Interview by Richard Marshall

'My interest in this topic cuts across traditional debates about egoism and altruism and reasons to be moral. What interests me is the extent to which there are different ways of being indifferent to things that genuinely matter; ways that can be more or less sensitive to their objects, or more or less dynamic with respect to their effects.'

' I see moral philosophy as continuous with the empirical study of human moralities and their psychology, anthropology, sociology, history and biology; but not as reducible to, or made redundant by, such a study. I think the questions that arise at the intersection between philosophy and these disciplines are not only among the most difficult that moral philosophers are faced with, but also among the most important.'

'When you read the work of writers such as Sidgwick, Moore and Ross in light of the recent literature in metaethics, it is easy to miss the fact that they were at least as interested in what moral knowledge consists in; where it comes from; and what entitles us to it as in the question of what, if anything, non-natural facts or properties might be like.'

'In a nutshell, the late Cambridge pragmatist invites you to do two things. First, when presented with some apparently problematic concept (such as ‘wrongness’), don’t rush to ask what the concept stands for, or represents. Ask instead what function, or role, that concept plays in human thought. Second, when presented with some apparently problematic philosophical claim (such as ‘Wrongness exists’), don’t rush to treat it as an ‘external’ claim about the relationship between the problematic discourse and the world.'

'What is interesting about Davidson’s view from my perspective as a moral philosopher is not so much the claim about convergence in values itself as that on Davidson’s theory the requirement of convergence in values is as basic as the requirement of convergence on non-evaluative facts.'

'Nagel, Parfit and Scanlon. I don’t agree that what these philosophers are doing individually can be fairly accused of being ‘no better than religious apologetics’. What I do think is that the institutional paradigm their work represents has a charge to answer with respect to its frequently coercive refusal to allow that philosophical enquiry is empirically tractable.'

Hallvard Lillehammer is a philosopher mainly focused on the interpretation and criticism of basic ideas in contemporary moral and political thought, including reason, objectivity, impartiality, autonomy, indifference and responsibility. Here he discusses indifference and ethics, autonomy, the relationship between ethics and empirical studies, a metaphysical first vs epistemology first distinction, issues with the Cambridge Pragmatists, ethics and the Darwinian challenge, Davidson and convergence, metaethics and Companions in Guilt arguments, constructivism vs error theory, and whether moral philosophy can be justified as an enterprise.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Hallvard Lillehammer: This is the hardest of your questions to answer because my entry into the philosophy profession happened as a result of a series of freak accidents, a lack of maturity on my own part, and acts of generosity on the part of others; all of which speak more to my socioeconomic profile than to the quality of my own decision making. Having said that, it is obviously possible to be a philosopher without being a salaried member of the university-industrial complex. So, adopting a wider perspective, I think I first became seriously interested in philosophy at school, with exposure to Nietzsche and Sartre, both of whom resonated with adolescent preoccupations; hermeneutics, which did not; and the ‘analytical school’, which I could not get my head around, but which left me with an ‘itch’. Much of what happened afterwards is attributable to that ‘itch’.

3:16: You’re interested in philosophical questions about ethics. Indifference is one topic you’ve thought about. So is indifference an ethical vice? Are there ethical reasons why I should care about other people, for example? Who is my neighbour? Why shouldn’t I just mind my own business?

HL: My interest in this topic cuts across traditional debates about egoism and altruism and reasons to be moral. What interests me is the extent to which there are different ways of being indifferent to things that genuinely matter; ways that can be more or less sensitive to their objects, or more or less dynamic with respect to their effects. For example, you could display a state of what I call object sensitive and dynamic indifference by devoting all your attention to your friends, while completely ignoring a stranger who ends up feeling excluded or unwelcome as a result. Moreover, this could be a pattern of behaviour that plays a social role that you yourself are largely unaware of. After all, you are just being super-friendly to your friends! This might then explain your shock or vehement denial when confronted with the fact that you and your friends are perceived as biased, unwelcoming, or otherwise engaged in systematically exclusionary behaviour. So, coming back to your question: there is no suggestion here that you are someone who does not care about other people.

3:16: You talk about ‘cultivating the virtues of indifference’. How should we do this, and why?

HL: The exclusionary indifference I described in answer to your last question has a virtuous flipside. Imagine a situation in which you and your friends are seated in a public venue adjacent to people you know who are having a private conversation. One socially beneficial norm in that case is that both groups are able to rely on one group not listening in to the other group’s conversation. A long time ago, the sociologist Ervin Goffman labelled such behaviours ‘protective practices’. Philosophers have much to learn from the empirical study of these, and other forms of context-sensitive indifference. For example, we live in a world where we are constantly bombarded by technologically sophisticated attempts to arouse our feelings in the service of commercial or political ends with which we do not, or should not, identify. So, coming back to your question: it could be a good idea to cultivate virtues of indifference in order to prevent your otherwise admirable concerns from developing into a cacophonous pathology. The practical challenge is to do so in an ethically responsible way.

3:16: Autonomy is highly prized in our society and many would argue that it should only be constrained if there are good reasons for this. Yet many are constrained – children, the mentally ill, the self-destructive, the murderously inclined and so forth. Before saying how such constraints might be justified, can you sketch for us how you understand autonomy given that there are competing claims about it – does it have value for you?

HL: ‘Autonomy’ is a technical term with a distinguished philosophical history, and I am happy to defer to that history so long as it makes room for a significant amount of pluralism. I have a lot of respect for the idea that one type of freedom that matters is the freedom of self-governance. I find this idea very helpful to make sense not only of the relationship between individuals and some of the social groups of which we are a part (such as ‘the state’), but also of the fact that none of us ever agreed to come into existence in the first place. One problem with this idea, though, is that it hard to sustain the view that this is the only freedom that matters.

3:16: So what justifications are given for constraining autonomy and can it be said that we actually owe people a duty to elicit consent regardless of their issues?

HL: The standard justification for constraining autonomy in the liberal tradition is the prevention of harm, either to Self or Other. On that topic, I have little to offer except a reminder of the old saying that hard cases make bad law. The issue I have been more interested in is the fact that the ethics of freedom, agreement and consent extends far beyond the domain of agents as characterized by standard accounts of autonomy. I think that among the freedoms that matter are freedoms that ask rather less of their subjects than some of the dominant theories of autonomy do, or ask rather different things of those subjects. One thought I take very seriously is that agents can have an interest in playing an active part in decisions concerning themselves that people make together, even if the relationship between the people involved is highly asymmetric with respect to their power, rationality or other abilities. I think something like that thought is needed to make sense of the grievance that is sometimes expressed by vulnerable persons who feel excluded from their own treatment by apparently caring others.

3:16: Should empirical studies of human morality – including its history and evolution - matter to ethics? Why would it matter that, for example, many of our morals originated within a religion? Surely we can judge the morality on a priori grounds? And why do you find Ross and Moore and French sociologists interesting in the ways they responded to the rise of the emerging moral sciences back in their day?

HL: I see moral philosophy as continuous with the empirical study of human moralities and their psychology, anthropology, sociology, history and biology; but not as reducible to, or made redundant by, such a study. I think the questions that arise at the intersection between philosophy and these disciplines are not only among the most difficult that moral philosophers are faced with, but also among the most important. The question of what to make of your claims to moral insight once you loose our grip on the kinds of grounding narrative that have traditionally invoked a Higher Being or the like is just one historically specific example of this combination of difficulty and importance, and one which is clearly manifested in some of the arguments and ideas about the foundations of moral knowledge that were produced in response to the emerging human sciences in the latter parts of the Nineteenth Century and the early parts of the Twentieth. As a philosopher I am interested in the fact that the way Moore, Ross, Sidgwick and others responded to these questions is very similar to the responses found in the contemporary literature on topics such as evolutionary debunking, for example. As a historian of philosophy I am interested in how these figures were able to set the agenda for the way that much of moral philosophy was carried on for the next hundred years in the Anglosphere, sometimes in disturbingly ignorant ways.

3:16: Your account flushes out a distinction between ‘metaphysics first’ approaches to ‘epistemology first’ approaches. What’s this distinction about, how has it played out in recent ethical philosophy of the last hundred years and is it still an issue that is helpful to make explicit and understand its history if we are not to be anachronistic?

HL: The question is arguably one of emphasis, because any satisfactory account of moral thought will obviously want to get both the epistemology and the metaphysics right. Yet when you read the work of writers such as Sidgwick, Moore and Ross in light of the recent literature in metaethics, it is easy to miss the fact that they were at least as interested in what moral knowledge consists in; where it comes from; and what entitles us to it as in the question of what, if anything, non-natural facts or properties might be like. To put the point slightly more provocatively than I probably should: with respect to at least one of the issues that what were fundamentally at stake for them, namely our entitlement to our moral convictions, the question of whether the objects of thought we call to mind when calling something good or bad, for example, should be classified as genuinely ‘real’ in virtue of not earning their place in a sparsely naturalistic account of facts or properties is of comparable significance to the adoption of one or another consistent accountancy convention.

3:16: You’ve raised issues regarding late Cambridge pragmatism – embodied in the figures of Huw Price and Simon Blackburn. So first, can you sketch for us what this position claims and historically where it came from?

HL: In a nutshell, the late Cambridge pragmatist invites you to do two things. First, when presented with some apparently problematic concept (such as ‘wrongness’), don’t rush to ask what the concept stands for, or represents. Ask instead what function, or role, that concept plays in human thought. Second, when presented with some apparently problematic philosophical claim (such as ‘Wrongness exists’), don’t rush to treat it as an ‘external’ claim about the relationship between the problematic discourse and the world. Treat it instead as a claim that is ‘internal’ to the problematic discourse itself (such as: ‘Some acts are just wrong’). The first of these invitations has the later Wittgenstein as one of its most prominent predecessors. The distinction embodied in the second is traceable to Carnap, among others. Yet the origins of late Cambridge Pragmatism obviously extend far beyond these two children of the late Habsburg Empire and across the Atlantic to the United States as well.

3:16: You think there is a problem about naturalism and this pragmatism don’t you, one which flushes out why the naturalist ‘master narrative’, as you call it, is linked to values. Can you explain your thoughts about this and what consequences follow for you regarding how we move forward with these values?

HL: The obvious challenge for the late Cambridge Pragmatist is to say something plausible about their choice of a ‘master narrative’ for describing the function, or role, that different concepts play in human thought. Blackburn and Price both explicitly endorse what they describe as a ‘naturalistic’ master narrative for this task. Yet why should we prefer this naturalistic master narrative rather than any alternative, and how can we coherently explain why we should favour this master narrative if we really take to heart the late Cambridge Pragmatists’ two invitations described in my answer to the previous question? If we wanted to play devil’s advocate we could say that the truths embodied in Late Cambridge Pragmatism seem rather like those ineffable truths that the early Wittgenstein gestures towards in the Tractatus as being ones that can only be shown, but not said. One response to this puzzle is to say that we can make our choice of master narrative in light of what we value. This response is broadly similar to a view that can be found in the writings of another philosopher associated with the label ‘pragmatism’, namely the late Hilary Putnam. There are also traces of it in Blackburn’s most recent work. It would be nice to be able to concur.

3:16: Darwinian evolution might be thought to erode the epistemic credentials of our ethical beliefs. Do you think it does – and does this support the Cambridge pragmatists anti-realist, deflationary position?

HL: In short: I do not believe that Darwinian evolution erodes the epistemic credentials of all our ethical beliefs, although the genealogical method of criticism that the Darwinian challenge exemplifies can be a potent tool in diagnosing the lack of justification or warrant for a wide range of individual beliefs and commitments, ranging from hostility based on prejudice to misguided customer loyalties based on manipulative advertising. If late Cambridge Pragmatism has anything interesting to say on this topic, it is in asking us to interpret the Darwinian challenge as an ‘internal’, or ‘first-order’, task of updating the content of our moral sensibility in light of our knowledge of the origins of that sensibility itself. I think that is a perfectly reasonable request.

3:16: Donald Davidson argued that convergence supported his objectivity claims about value judgments. Was he wrong about this?

HL: Davidson argued that we interpret each other as ‘believers of the true’ and ‘lovers of the good’, and that our ability to do so presupposes that we largely converge both in what we believe to be true and in what we judge to be good. What is interesting about Davidson’s view from my perspective as a moral philosopher is not so much the claim about convergence in values itself as that on Davidson’s theory the requirement of convergence in values is as basic as the requirement of convergence on non-evaluative facts. This implies that one standard way of framing the problem of whether values are objective (i.e. by questioning the truth of evaluative claims against the background of the agreed truth of non-evaluative claims) is fundamentally misconceived. Of course, there are those who would wish to do away with talk of desires and beliefs altogether, along with the rest of the propositional attitudes. I have no theoretical stake in that debate. What has interested me is the provocative idea that there are conceptual connections between evaluative claims on the one hand and the way we find it natural to understand each other as minded on the other that can be harnessed to make progress on difficult questions in metaethics.

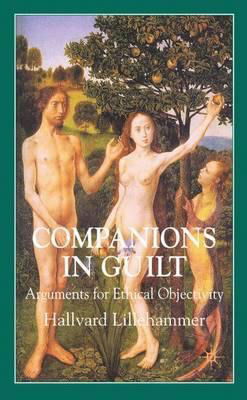

3:16: So we’re right in the meta-ethical rabbit hole now. Can you quickly say what you think meta-ethics is and then sketch for us what the ‘companions in guilt’ argument is within this domain, saying why it’s deemed important and why you don’t think it improves on arguments from analogy nor entailment?

HL: Metaethics is the project of attempting to gain a better understanding of the nature and status of ethical claims. One way of doing so is to make lateral comparisons with other kinds of claims about which we think we have a firmer grip. In particular, there could be illuminating connections between ethical claims and non-ethical claims (such as claims about colour, rationality or scientific theories), the latter of which do not seem to be problematic in the way that ethical are often said to be. That’s what ‘companions in guilt’ arguments are about; arguments from analogy and entailment being two forms that such arguments can take. Apart from their probative value in metaethics, the primary interest of these arguments resides in how they allow us to locate ethics respect to other areas of thought that philosophers have historically been interested in. The fact that studying such arguments is also a way to obtain a better understanding of those other areas of thought as well is another argument in favour of their theoretical interest.

3:16: Constructivism and error theory both say that morals are not discovered but they are constructed. Error theory goes further than constructivism in that it claims that moral thought aspires to be more than just something made up, but is wrong about that aspiration. Constructivism remains silent on this further issue. Why do you think constructivism is the better way to go?

HL: I think it is more plausible that some form of moral constructivism is true than that a universal moral error theory is true because constructivism incorporates the more plausible commitments of error theory while stopping short of endorsing its more tendentious commitments. Among the more plausible commitments of constructivism and error theory I count the claim that moralities are socially constructed human artefacts. Among the more tendentious commitments of error theory I count things exemplified by the following: unless I am implicitly committed to the existence of response-independent non-natural properties with purely extensionally specifiable identity conditions that make normatively inescapable claims on all agents on pains of irrationality, I cannot competently and sincerely make a genuine moral judgement.The paradox of most contemporary forms of universal moral error theory is that they are really a kind of dogmatism dressed up in skeptical disguise.

3:16: A crucial question for you as a moral philosopher is what is the point of moral philosophy – can it be justified as an enterprise? A Nietzschean might push back and attack morality for its commitment to untenable descriptive (metaphysical and empirical) claims about human agency, as well as for the deleterious impact of its distinctive norms and values on the flourishing of the highest types of human beings. And even if not a Nietzschean, philosophers like Scanlon and Parfit and Nagel defending the objectivity of moral opinions on the grounds that they were confident in the good reasons they had for them (or in their apparent truth), quite independent of whether there was evidence for them of the kind we would expect in any other domain of human inquiry thought to be epistemically reliable, strike many as being no better than religious apologetics. And if constructivism is right then is there any role for the moral philosopher now as opposed to the psychologist or the neuroscientist or biologist – or better still, why not leave it to Proust and the novelists and poets?

HL: You have presented me with quite a challenge in asking me to say something sensible about Nietzsche, Nagel, Parfit and Scanlon all in one breath. Yet as far as I’m concerned, each of these writers is a paradigmatic specimen of someone doing ‘moral philosophy’ as I understand it, although they obviously differ greatly; for example in the extent to which they are prepared to let philosophy ‘leave everything as it is’, in Wittgenstein’s phrase. The genealogical method you ascribe to Nietzsche and for which he is justly famous is one I have already registered my respect for, even though it is not the exclusive property of Nietzscheans and has a tendency to inspire arguments that overreach. I would place Nietzsche’s own use of the method to reject the cluster of views he identifies as ‘morality’ in that category. One important lesson I do take from Nietzsche’s use of this method, however, is that a philosophical outlook is sometimes a better guide to the psychosocial circumstances of its author than to the nature of its subject matter.

All of which brings me to Nagel, Parfit and Scanlon. I don’t agree that what these philosophers are doing individually can be fairly accused of being ‘no better than religious apologetics’. What I do think is that the institutional paradigm their work represents has a charge to answer with respect to its frequently coercive refusal to allow that philosophical enquiry is empirically tractable. On the one hand, this refusal has arguably helped to sustain a culture of stability and in-house rigor that has kept some of the more intellectually subversive elements of our discipline at bay during the course of recent culture wars. On the other hand, I think you are right to be suspicious of the tendency of this institutional paradigm to postulate truths that are ‘basic’, ‘ultimate’ or ‘fundamental’ just at the point where things begin to look interesting of problematic from the point of view of those we in the profession pretentiously refer to as ‘non-philosophers’.

As far as the novelists and poets are concerned: I don’t see any contradiction in the idea of a great philosophical work of art or an artistically accomplished work of philosophy. Which is not to say that the production of either is easily achievable.

3:16: And finally, for the curious readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

HL: This is not a list of ‘greatest hits’, but the works of five philosophers who have influenced me. I count myself as having been extremely fortunate to be influenced by them.

Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy(Fontana 1985)

Onora O’Neill, Constructions of Reason: Explorations of Kant’s Practical Philosophy (Cambridge 1989)

Simon Blackburn, Essays in Quasi-Realism (Oxford 1993)

Malcolm Budd, Values of Art: Pictures, Poetry and Music (Penguin 1995)

Raymond Geuss, Morality, Culture and History: Essays on German Philosophy (Cambridge 1999)

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees