Is International Law Law, and Other Questions

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I would say that the most important issue raised by international law for the question of the grounds of law is that of whose beliefs and attitudes count for the fixing of the political/social grounds of law.'

'Positivism and nonpositivism differ on the role of moral considerations in determining the content of the law in force. All sensible views treat matters of brute social/political fact as partly determining law’s content but some, the nonpositivists, have it that moral judgment is inevitably required in interpreting legal materials to figure out what the law says.'

'I think it does matter what the content of the law is. And I actually think it matters even more for international law than for domestic law (with the exception of domestic law that applies to the highest state officials, such as a president)'

'Though I’m not at all sure about it, it seems to me that what is distinctive about legal orders, including international law, is a certain attitude we take toward it about enforcement, that of enforcement’s in-principle legitimacy.'

'I think that the critics from the right would be more likely to say that I believe that all property is theft!'

Liam Murphy works in legal, moral, and political philosophy and the application of these inquiries to law, legal institutions, and legal theory.' Here he discusses international law, what grounds such law, positivist and non-positivist responses to the grounding issue, Hart's view, whether international law is law, inequality and law, Parfit's approach, Picketty, ethical and political stakes in the debate regarding the concept of law, Raz and Dworkin, law and tax, and why philosophy of law needs to get beyond the positivism/non positivism debate.

3:16: Why did you become a philosopher?

Liam Murphy: In my first year at The University of Melbourne, in 1978, I was lucky enough to take an experimental interdisciplinary first-year course with Judith Brett called Problems of Language in the Twentieth Century. We read psychology, literature, and philosophy—Russell and Wittgenstein. I enjoyed the philosophy the most and was best at it too, so I went on to the honors philosophy track. I don’t think I would have gone into philosophy without Brett’s wonderful course. As an undergraduate I remained mainly interested in the philosophy of language, but it became clear by the end of my honors year that I didn’t have anything to contribute to the subject. So at that point I turned finally to taking the law part of my combined arts/law program seriously. But I did continue to go to philosophy tutorials that my undergraduate mentor Barry Taylor gave at Ormond College, just because Barry was wonderful, and it was there that I discovered ethics. I hadn’t studied ethics as an undergraduate at all; the work I did encounter had struck me as bourgeois moralizing. But then Barry had us read papers by Thomas Nagel and Derek Parfit, and it changed my life. I still remember my excitement at discovering that philosophy did have something to offer on the moral and political questions I was most exercised by. I decided to go on to graduate school to do ethics. So the short answer is this: In about 1983 I read Parfit’s “Prudence, Morality, and the Prisoners’ Dilemma” and most of the papers in Nagel’s Mortal Questions.

3:16: Let’s start with two key questions relating to international law – law beyond the state – what are the grounds of such law, and what makes a normative order an order of law? Beginning with the first question about the grounds of international law can you sketch for us what the distinctive issues are when discussing international rather than state law?

LM: Both international and domestic law are normative orders distinct from morality, even if morality may constrain or guide legal interpretation. Whether or not morality is involved, at least part of the grounds of law are matters of social/political fact. It is easier to say what those matters of fact are in the case of domestic law, since members of the typically well-functioning three branches of government, along with most legal scholars and other people with knowledge of law, all treat the same facts as the law-grounding ones. Constitutionally acceptable legislative enactments, for example, are among the factual grounds of law because almost everyone with a life in the law agrees that they are. In the case of international law, there is more disagreement about fundamental legal sources. For example, there is disagreement about whether a state can be bound to a legal norm to which it has not either tacitly or explicitly consented, such as so-called jus cogens (compelling) norms. But what’s philosophically more important is that there is disagreement about whose views on the matter count. If state officials in many countries were to disagree with most international jurists and legal scholars about the status of jus cogens norms, where would we go from there? So I would say that the most important issue raised by international law for the question of the grounds of law is that of whose beliefs and attitudes count for the fixing of the political/social grounds of law. The importance of this issue is obscured somewhat in the domestic case where, at least where things are going well, well-functioning state institutions produce a degree of convergence that allows us to neglect the question.

3:16: You look at positivist and non-positivist responses to the issue. For the uninitiated, could you first say what legal positivism and non-positivism and whether you think international law has been neglected by legal philosophers (except Kelsen) because of HLA Hart?

LM: Positivism and nonpositivism differ on the role of moral considerations in determining the content of the law in force. All sensible views treat matters of brute social/political fact as partly determining law’s content but some, the nonpositivists, have it that moral judgment is inevitably required in interpreting legal materials to figure out what the law says. Others, the positivists, have it that though moral judgment may well be needed if a judge is to make a decision, it is not required in order to determine what the law (already, before the decision) says; once your interpretation draws on independent moral judgment you are making law rather than finding out its content. I should say that the most important nonpositivist, my late colleague Ronald Dworkin, in his final writings on the topic abandoned what I just attributed to “all sensible views.” He concluded that legal interpretation was moral judgment all the way up and down—that is, matters of social/political fact do not determine any part of law’s content unless there is moral reason for that. I think this kind of view denies the reality of law as a normative order distinct from morality and is mistaken.

[HLA Hart]

I don’t think Hart is to blame for the neglect of international law among legal philosophers as he did after all write a chapter about it The Concept of Law. It was not a very strong chapter, but that should have made it even more appealing as a target for critics!

3:16: So what is at stakes for both these positions regarding the ground of international law?

LM: Well, some think nothing is at stake in the debate about the grounds of law for either the domestic or the international case. They say that the dispute is just about what we say and makes no difference to what we should do. Judges, in particular, don’t need to have a view about whether all they do is apply law (nonpositivism), or whether they both apply it and extend it by appeal to moral considerations from outside law (positivism). But I think it does matter what the content of the law is. And I actually think it matters even more for international law than for domestic law (with the exception of domestic law that applies to the highest state officials, such as a president). The reason is that in the absence of reliable, effective enforcement, and in the absence even of courts of compulsory jurisdiction, states must for the most part apply international law to themselves. So it’s important to know the grounds of law in order to be able to figure out what the law is, and that’s important because it is important that states follow international law.

3:16: Hart thought that international law wasn’t a system but just a set of rules binding simply in virtue of being accepted as such. This seems to make the validity of law direct and removes the need for any rule of recognition doesn’t it? What do you make of this position?

LM: That’s what he argued, that there was no rule of recognition in international law, meaning that there were no criteria of validity and so, yes, all validity is direct. I think it helps to notice that he could equally have said that international law was all rule of recognition, because for Hart the rule of recognition is not valid because of some further criterion of validity but rather just in virtue of being accepted by legal officials as valid. He appeared to think that all international law was customary law and that there is no difference between customary law and what an international rule of recognition would be, and so a (separate) rule of recognition would play no role. But even if treaties are not a separate source of law, contrary to what seems the natural view (requiring at least one criterion of validity), there’s a problem. The content of customary international law is fixed by state practice and opinion. But if there were an international rule of recognition, the beliefs and attitudes of others, such as jurists and legal scholars, should also count. It seems far better to say that the content of customary law is fixed by state practice and opinion because that is a (second) criterion of validity generally accepted by those with a life in international law.

3:16: Distinct from the question of the grounds of law is the second question about what makes a normative order law, as opposed to, for example, positive morality. How do you think we should go about answering this question which boils down to: Is international law law?

LM: I’m generally leery of “What is X?” questions in philosophy. On the other hand what makes law a normative order distinct from positive morality does seem to be an important question. There are good arguments, I think, for the moral importance of high state officials obeying law both domestic and international. As to how to go about answering the question, there seems to be no alternative to reflecting on what it seems natural to say in a range of cases. Can a normative order be law if it lacks courts of compulsory jurisdiction? Sure. A centralized enforcement apparatus?; A legislature? Also yes. So is there no difference between international positive morality and what we call international law? No difference between a legally binding treaty and a “soft law” agreement stipulated not to have legal force? Well, no, that doesn’t seem right. Though I’m not at all sure about it, it seems to me that what is distinctive about legal orders, including international law, is a certain attitude we take toward it about enforcement, that of enforcement’s in-principle legitimacy. There is a case for enforcement of international law that is absent in the case of international positive morality; this is what makes international law law, even if it is not, in fact, enforced.

3:16: Conventional jurisprudence currently doesn’t recognise a global administrative law: so where does that leave such law?

LM: Well, I don’t know. It has always seemed to me more a proposal—there ought to be a global administrative law. I agree it seems like a good idea.

3:16: Inequality might be something that we’d like international law to tackle. You’ve looked at Piketty’s great book about our contemporary inequalities. For you Piketty doesn’t engage with either utilitarian or welfarist to economic justice. His approach to economic justice is deontological. Before saying what you mean by this, can you sketch the approaches that he doesn’t use so we can see how different his approach is to answering the question why inequality matters?

LM: Well, utilitarianism assesses institutional arrangements, including the tax and transfer system, by looking for that arrangement that maximizes aggregate welfare. Welfare economics, which descends from utilitarianism, is skeptical about the idea of aggregate objective welfare and uses instead cost-benefit analysis as the criterion. Cost-benefit analysis looks, roughly, for the outcome where the gainers are better off by their own lights even after having (hypothetically!) compensated the losers. I don’t find either view plausible as neither takes the distribution of welfare seriously. The most plausible view in this neighborhood, I believe, is some version of what Derek Parfit, developing one strand in Rawls, called prioritarianism (I wish there were a better name): Justice requires promoting general welfare but increases to the welfare of the worse off matter more, are given extra weight. This kind of view is sensitive to the moral difference between making a very badly off person better off and making a much better off person better off by the same amount, but does not regard equality of welfare as itself a value or a norm of justice.

3:16: So what is his deontological approach – which I take it to be about rights even though you make clear it’s not property rights - and why does he think it superior to the other approaches in answering the question as to why inequality matters?

LM: Piketty did write a great book but excavating the political morality driving it, or his reasons for favoring that political morality, isn’t terribly easy. In my interpretation, which he didn’t disagree with at a conference where I first presented that paper, he follows some version of what has come to be called “luck egalitarianism.” On this view, as you note, there is no appeal to natural property rights—property is just one aspect of the overall institutional arrangement the justice of which is to be assessed, just like on utilitarian or prioritarian views. What makes the view deontological—which just means that arrangements can be just or unjust for reasons other than their effects on social outcomes such as welfare—is that the demand for justice is a demand of fairness for equality, subject to deviations for which individuals can be held responsible. So if I’m worse off than you because I’m lazy, that’s not unfair or unjust, but if it’s because I was born poorer or shorter, that is unjust. This kind of view has had an influence in recent decades that I find surprising. Its origins can be found in a celebrated pair of articles by Ronald Dworkin, but Dworkin was always clear that he was defending the way markets distribute rewards. The problem with markets, for Dworkin, is that we don’t all start with the same resources; but if we did, anyone who was worse off than another would have only themselves to blame.

The abstract claim of luck egalitarianism that just outcomes should remove luck and track only responsible choices is not plausible unless the space of options among which we can choose is itself morally endorsed in some way. As I say, Dworkin knew this and defended the way in which markets rewarded decisions--something like, to each according to their marginal product. I don’t find this plausible, and I can’t see that Piketty would either, since his book contains compelling critiques of various claims that have been made about desert in market returns. But he doesn’t offer any other account of why economic justice should track people’s responsible choices. On this topic, by the way, in my view by far the best thing written is chapter 6 of T. M. Scanlon’s What We Owe to Each Other. Anyone tempted by luck egalitarianism should be required immediately to read Scanlon on the significance of choice.

3:16: Is it your view that the reason why we need to uncover what is going on with capital is that we want to know where the money is, and how to get it, in order to do something about the humanitarian catastrophe that is our current and future world – in other words that we should be focusing on the poor. You say that ‘Piketty, by contrast, appears to be motivated at least in part by a sense that where possible and practicable, it makes sense to distinguish at least among those who are obviously more or less meritorious with respect to their economic situation, and that in a fair society institutions would be structured to reduce the role of gross luck in circumstances.’ Can you say something about your disagreement with Piketty in this and say what changes would you make in law to bring about necessary change?

LM: I think Piketty is, surprisingly, too moralistic about distributive justice and, as I just said, he has not explained the theory behind that moralism. When it comes to inequality and economic justice, I don’t myself think about whether a particular rich person deserves their riches. That’s not because I think all rich people do deserve their riches, but because I think no one deserves their place in the economic distribution in any sense that is relevant for the design of economic institutions. So unlike Piketty, I am not inclined to look more favorably at fortunes earned through work rather than through capital accumulation or simple inheritance. To my mind what is morally problematic about the great fortunes we currently see is not that some of them are undeserved but that the money could be used to benefit the huge numbers of people who are so badly off. So yes, I favor a wealth tax as a source of revenue. But the test of any particular legal arrangement is its long term effects. Taking into account (of course) effects on incentives to work and save, we want that institutional structure that makes people better off, giving priority to those who are worse off. It may be, in fact, that at a certain point, the worst off are so well off that justice requires no further transfers from the even better off. In a nutshell, I’m not concerned about desert, or equality for its own sake, but about all people living good lives.

3:16: What are the ethical and political stakes of the debate over the concept of law and why do you say that the instrumental arguments regarding whether we should be positivists or not have no chance of changing the world such that either view can be said to be true or not. Doesn’t that render the arguments pointless?

LM: Bentham, Hart, and Kelsen all thought that nonpositivism led to what Bentham called quietism, a kind of illicit justification of the status quo. Kelsen was actually clearest on this. His thought was that if saying that a political coercive order is an order of law means by definition that it is in some sense good or connected to morality, then we are going to unthinkingly regard our own political coercive order as in some sense good or connected to morality, for we are all inclined to think our own political coercive order is an order of law. Since a skeptical, evaluative attitude to our political coercive order is better than a complacent one, we are better off rejecting the nonpositivist account and embracing positivism. Now unlike many, I actually find this line of thought very plausible, and my own positivist inclinations are probably connected to this kind of worry. And I’d go so far as the claim that it would be better if we were all positivists. But the problem is that even if this instrumental claim is true, it doesn’t really help with anything so long as many people continue to embrace a nonpositivist conception of law. The concept of law is so deeply embedded in our social and political practices that the chances for successful conceptual entrepreneurship seem slim.

3:16: What are philosophers of law doing when they say they’re examining concepts? You’ve looked at the case of Joseph Raz to investigate this haven’t you, so perhaps you could explain what the issues are in looking at Raz’s use of concepts and how it helps understand what conceptual analysis really is in this branch of philosophy?

LM: Raz (like Dworkin, whose approach is actually rather similar) aims to be providing an account of the concept of law that (he believes) we all share. The thought is that disagreement between positivists and nonpositivists is actually superficial and that at a deeper level we all agree. So it is possible to be mistaken at the unreflective everyday level about the content of the concept you are actually employing. The way Raz aims to bring out the true content of the concept is to note its connection with another concept; reflection on the implications of that other concept for the concept of law will then reveal the truth about the concept of law. For Raz the important adjacent concept is that of authority which is connected to law in that law necessarily claims authority. But now, the argument continues, if we reflect on what law will have to be like in order to have authority, we’ll see that we must be able to determine its content without appeal to moral argument. Therefore, positivism. Raz is clear that this argument is not just conceptual in the sense that everyone who understands it will automatically agree; it involves normative argument as well. The problem I have with the argument is that it has several steps that could well be resisted, and seem certain to be resisted by anyone who is already in the grip of a nonpositivist conception of law. The same general point applies in reverse to Dworkin’s argument for nonpositivism. I am inclined to think that no compelling argument is available to show that we all share the same concept of law.

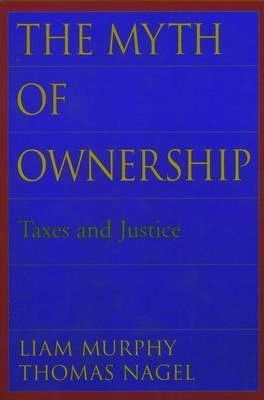

3:16: You’ve engaged with the idea that taxation and our rights. Some on the right have wrongly supposed you argue for the position that all taxation is theft. What is it you are actually arguing for?

LM: I think that the critics from the right would be more likely to say that I believe that all property is theft! What Thomas Nagel and I argue in our book on taxes and justice is that pretax income is not a morally significant baseline for thinking about tax justice. Our title, The Myth of Ownership refers to the myth that people own, in a morally significant sense, their pretax income. Pretax income is itself the output on the overall economic and legal system. It does not reflect natural moral property rights both because there are none but also because what we get, pretax, is the result of a myriad political decisions, including decisions about taxation. So the traditional way of thinking about justice in taxation in terms of a fair distribution of tax burdens as measured against pretax income is profoundly wrongheaded. What matters to economic justice is outcomes—the post-tax distribution. We should design our tax code, as but one important part of the overall economic/legal set-up, so that justice in outcomes is achieved. As we say in the book (it was Nagel’s coinage), pretax income is a mere accounting figure.

3:16: As a take home, could you say what you think is at stake in the debates about law and what you think should be the approach to respond to the seemingly intractable disagreements that we find in philosophy of law, some of which you’ve discussed earlier? I guess the general question is whether philosophy of law is doomed to stay inward looking and rather arid?

LM: Well, I think that there is a pretty widespread consensus that legal philosophy needs to move beyond the positivism/nonpositivism debate. So if you think about philosophy of law in a broad sense, to include philosophical reflection on particular legal institutions, the field actually looks pretty good at the moment—very strong philosophical work is being done on private law and criminal law, for example. I myself have been working on the philosophy of private law, and thinking about tax again, and also about issues in the philosophy of international law beyond the two questions about the nature of law with which we began. So I don’t think philosophy of law is doomed to stay arid and inward looking, but that does require broadening the set of questions it is concerned with.

3:16: And for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

LM: I’m going to cheat by taking Rawls’s A Theory of Justice as well as Hart’s and Dworkin’s works in jurisprudence for granted.

Thomas Nagel, The View from Nowhere

Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons

Joseph Raz, The Morality of Freedom

Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Realm of Rights

Bernard Williams, Truth and Truthfulness

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees