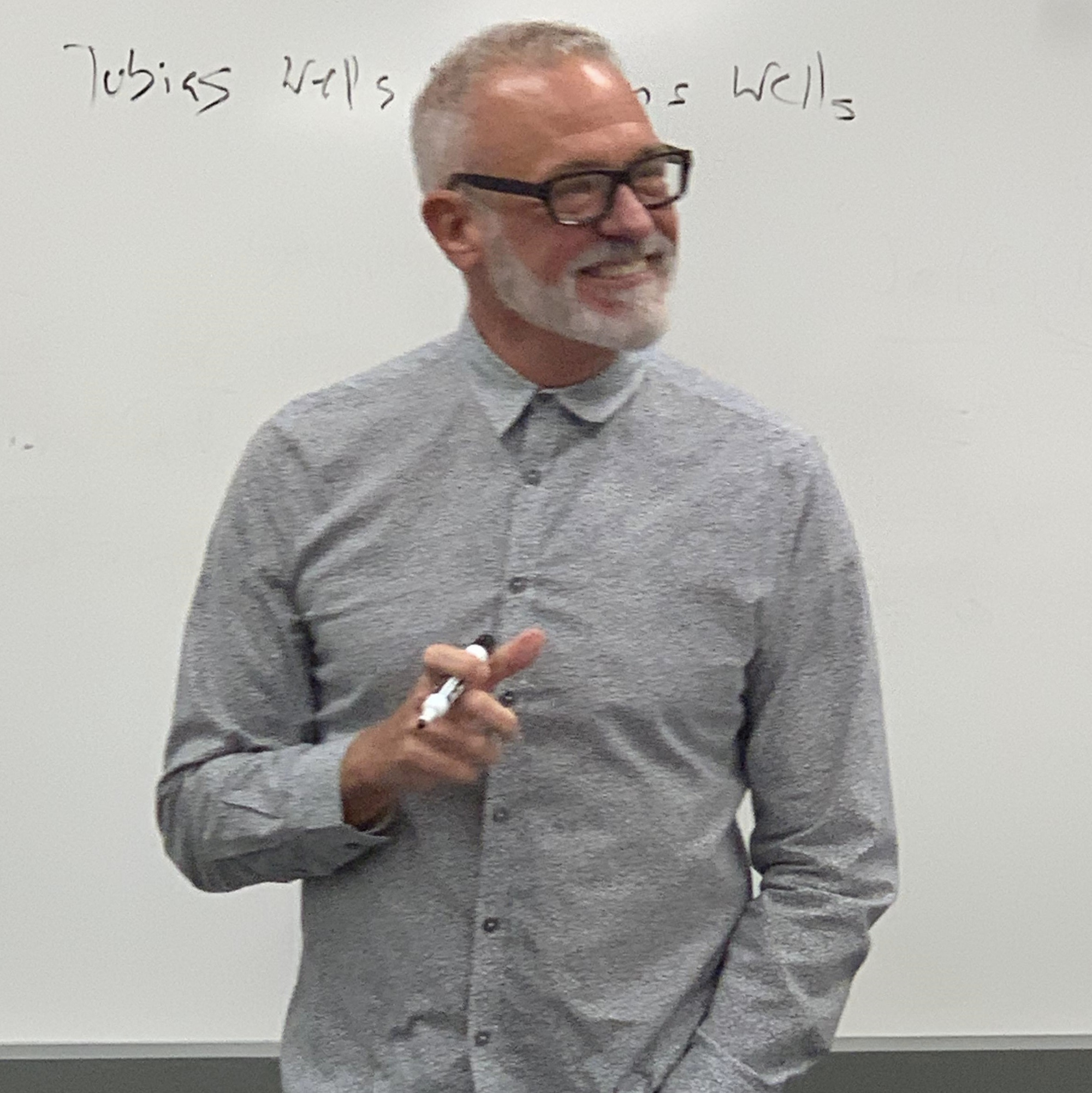

Jeffrey King and Felicitous Underspecifications

'...felicitous underspecification is the phenomenon whereby a contextually sensitive expression is not assigned a unique semantic value in context but the use of the expression is nonetheless felicitous. Instead, it is assigned a range of candidate semantic values in context.'

'...some philosophers don’t believe in propositions. I think these days such philosophers are in the minority (but maybe I am in a “pro proposition bubble” and don’t realize how many philosophers don’t believe in propositions). Of course, among those who believe in propositions there are differences of opinion about what they are.'

'I believe there are impossible worlds. Given that you accept possible worlds, as both I and Stalnaker do, whether you can plausibly deny that there are impossible worlds can be very much influenced by what you think possible worlds are. For example, suppose you think possible worlds are sets of propositions. Then it looks like it will be very hard to deny that there are metaphysically impossible worlds. For there are sets of propositions that contain metaphysically impossible propositions or propositions whose conjunctions are metaphysically impossible.'

Jeffrey C. King is a Distinguished Professor of Philosophy known for his works on philosophy of language. Here he talks about his latest book concerning the notion of felicitous underspecification, Stalnaker’s idea of ‘common ground’ and updating sets, the matter of context, and implications for the metasemantics of contextually sensitive expressions. He then discusses the nature of propositions, why such a discussion is on the interface between metaphysics and philosophy of language, why he thinks propositions are facts and then goes on to discuss Stalnaker's "two dimensional" account of the necessary a posteriori on which there is no single proposition that is both necessary and a posteriori, the notion of anaphora and in particular the puzzles about anaphoric pronouns , why Stalnaker is wrong to deny the existence of metaphysically impossible worlds and why philosophers are getting involved in what might look like linguistics.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Jeffrey King: I was really into mathematics and physics in high school and when I started college, that’s the sort of stuff I thought I wanted to do. In my sophomore year, I was majoring in math and I was taking a set theory course. On the last day of the course the professor started talking about axiomatizing set theory as a first order theory. I hadn’t taken any logic and I didn’t understand what he was saying. After the class I went up and began asking the professor to explain in more detail what he had been saying. He said that it was sort of a long story but that a professor in the philosophy department was teaching a class on first order predicate logic the next term and that if I took the course I would understand what he had been saying.

I did take the course and fell in love with logic. I then took a course on Frege and Russell from the same professor and was hooked. I planned to major in mathematics and minor in philosophy but the more philosophy I took, the more I loved it. Eventually, I majored in philosophy and minored in mathematics. When time came to think about what to do after my undergraduate education, I realized that I wanted to continue studying philosophy. I decided to go to grad school in philosophy. I knew that the job market in academic philosophy was very bad (some things never change!), so I planned to get my Ph.D. in philosophy and get on with my life after that by pursuing some other career. It didn’t turn out that way.

3:16: You’ve written a book about felicitous underspecification and argued that contextually sensitive expressions have felicitous uses in which they lack unique semantic values in context and then formulated a rule for updating the Stalnakerian common ground in cases in which an accepted sentence contains an expression lacking a unique semantic value in context. So let’s see if you can take us through your ideas here. First of all then, can you set out what felicitous underspecification is – and why philosophers have found it interesting? Is there a history to the puzzle? (And what’s infelicitous underspecification – and why isn’t that of philosophical interest?)

JK: Yes, the book is Felicitous Underspecification: Contextually Sensitive Expressions Lacking Unique Semantic Values in Context (2021, Oxford University Press). As you correctly say, felicitous underspecification is the phenomenon whereby a contextually sensitive expression is not assigned a unique semantic value in context but the use of the expression is nonetheless felicitous. Instead, it is assigned a range of candidate semantic values in context. Here a real-life example. I was out surfing with my friend Glenn at Lost Winds beach. There was a group of fifteen or so surfers a few hundred yards down the beach. They were of varying abilities but I kept noticing that members of an ill-defined subgroup kept getting incredible rides. As I watched a member of this group get yet another great wave, I pointed their direction and said ‘Those guys are good!’. As I said, I couldn’t make out the exact group of good surfers and so didn’t intend any unique group to be the semantic value in context of my use of ‘those guys’ and it seems clear that nothing else in the context of utterance determined a unique group. Instead, there is a range of overlapping groups that are legitimate candidates for being the semantic value in context of my use of ‘those guys’ (I think the range was determined by my intentions in uttering as I’ll discuss later). But my utterance was felicitous. So this is an instance of felicitous underspecification.

Second quick example. Consider a view of a gradable adjective like ‘cold’ on which it gets assigned a degree d of coldness in context c. Then in c, ‘cold’ is true of anything whose degree of coldness is d or colder. Suppose I dive onto the ocean one spring day and when I get out of the water I say to my wife ‘The water is cold.’. It is easy to imagine the case in such a way that neither my intentions in uttering nor anything else determined a unique degree of coldness as the semantic value in context of ‘cold’. Rather, again, I think my intentions determined a range of candidate semantic values in context for ‘cold’. But once again, my utterance is perfectly felicitous. So again, this is a case of felicitous underspecification.

I don’t think there is much of a history of studying the phenomenon though Chris Barker and John MacFarlane have done work on gradable adjectives that is very closely related. As to whether, and if so why, philosophers have found the phenomenon interesting, I don’t think that is for me to say. I’ll just say that I hope they find it interesting! Actually, this does lead into your final question here. Infelicitous underspecification has long been noted. Suppose I am standing on the San Clemente Pier looking at the beach where the competitors in the one mile swim race in the San Clemente Ocean Festival have gathered for the start of the race. There are about one hundred swimmers on the beach and focusing my attention on one of the swimmers, I say ‘He looks fit.’, where there is no way for my audience to know who I am trying to say something about. In such a case, it seems extremely plausible that my pronoun has not been assigned a unique semantic value in context (that will be so on my view of how pronouns get assigned semantic values in context) and the utterance is infelicitous. This isn’t surprising to people because it is natural to think that a contextually sensitive expression is looking to be assigned a unique semantic value in context and so when it doesn’t get assigned one, infelicity will result. That’s why I hope philosophers will find the phenomenon of felicitous underspecification surprising and interesting: it shows that the natural thought that not assigning a contextually sensitive expression a unique semantic value in context inevitably results in infelicity is false.

3:16: You have two questions. The first is: what is a speaker asserting or saying when they use a felicitous underspecification? So how do you tackle that?

JK: I raise this question in the book but I don’t answer it. Instead, I swap it out for what I view as the more tractable question of how conversational participants update the Stalnakerian common ground in cases of felicitous underspecification (see next question). I do suggest in the book that perhaps this update just is what the speaker asserts in cases of felicitous underspecification. I am now inclined to think that is right. For one thing, in cases of felicitous underspecification the speaker is committed to the update and that suggests it is what she asserted.

3:16: You also tackle the situation in the context of a conversation where someone uses this, how do the conversational participants update the conversational set? This presupposes understanding Stalnaker’s idea ‘common ground’ and updating sets so could you sketch for us what the issue is and how you go about solving it?

JK: Roughly, the Stalnakerian common ground at any point in a conversation is the set of propositions that conversational participants mutually knowingly accept for the purpose of the conversation at that point in it (for aficionados, I am assuming the context is nondefective). The context set is the set of worlds in which all common ground propositions are true.

We also need Craige Roberts’s notion of the immediate question under discussion. Roughly the immediate question under discussion at a point in a conversation is the question conversational participants are primarily attempting to answer at that point in the conversation. The q-alternatives for a question are roughly the allowable answers. So consider the question ‘Who is here?’ asked in a context in which the people under discussion are Mary, Glenn and Rebecca. Then the set of q-alternatives for the question is the following set of propositions {Mary is here, Glenn is here, Rebecca is here}. A partial answer to a question q is a proposition that together with the common ground entails that at least one of q’s q-alternatives is true or that it is false. In such a case, say that the proposition together with the common ground settles at least one of q’s q-alternatives. A complete answer to a question q is a proposition that together with the common ground settles all of q’s q-alternatives. Finally, an answer ϕ to a question q in context cis a better answer to q than is ψ in c iff ϕ together with the common ground in c settles more of q’s q-alternatives than does ψ.

Now consider a case of felicitous underspecification. It is common ground that Perez owns a car and leases a car. He drives each frequently and if someone were to point at either car and ask whose car it is we would without hesitation reply ‘Perez’s’. It is also common ground that Perez’s friend Cindy, who has no car, needed to go downtown today for an interview. You ask me how Cindy got to her interview today. So this is the immediate question under discussion. I say:

1. Cindy got to her interview by borrowing Perez’s car.

Suppose that nothing in our conversation hangs on which car Cindy borrowed and that we were solely concerned with how she got downtown (bus, metro, Uber, borrowed car, driven by someone, etc.). Indeed, suppose we don’t know which car Cindy borrowed but just that she borrowed one from Perez. Further, suppose the q-alternatives are {Cindy got to her interview by bus, Cindy got to her interview by metro, Cindy got to her interview by borrowing the car Perez owns or the car Perez leases}. We can suppose that it is common ground that Cindy availed herself of only one means of getting downtown. I assume that possessives are looking to be assigned two-place relations as semantic values in context. So in ‘Annie’s book is good’ we can imagine the possessive getting assigned the relation x wrote y in context so that the sentence is true in that context iff the book Annie wrote is good. Now it is easy to imagine that nothing in the context in which 1 was uttered picks out a unique two-place relation that is assigned to ‘Perez’s car’ in 1. 1 is nonetheless felicitous and so we have a case of felicitous underspecification. The candidate semantic values in context for the possessive in 1 are the following relations: x owns y and x leases y. Hence, the following are the candidate propositions in context for 1:

1a. Cindy got to her interview by borrowing the car Perez owns.

1b. Cindy got to her interview by borrowing the car Perez leases.

Call the disjunction and conjunction of 1a and 1b the candidate propositional updates in context for 1. Now here is my update rule. Suppose LF ϕ containing an instance of felicitous underspecification is uttered in context c and the candidate propositions for ϕ in c would update the context set in c differently:

Felicitous underspecified update (FUU)

Given c’s context set cs, update cs with the weakest candidate propositional update U for ϕ in c, if any, such that: 1. it gives a partial answer to the immediate question under discussion while adhering to Gricean maxims and not being ruled out by the common ground; and 2. no stronger candidate propositional update for ϕ in c gives a better answer to the immediate question under discussion than does U while adhering to Gricean maxims and not being ruled out by the common ground. In the present case, FUU predicts that the update is the disjunction of 1a and 1b since this gives a complete answer to the immediate question under discussion and is weaker than the conjunction of 1a and 1b. The conjunction is also ruled out by the common ground since it is common ground that Cindy employed only one means of getting downtown.

3:16: Why are sentences containing felicitous underspecified uses of supplementives felicitous in the context in which they are uttered?

JK: Two reasons taken together: 1. Conversational purposes at the point in the conversation at which the instance of felicitous underspecification occurs don’t require that the underspecified expression be assigned a unique semantic value in context and are adequately served by associating a range of candidate semantic values in context with the expression in question (I make this idea more precise in Chapter 5 of the book). 2. The instance of underspecification possesses (two or more) features that I call felicity enhancers. As the name suggests, I think these felicity enhancers contribute to an instance of underspecification being felicitous. I identify five felicity enhancers in Chapter 6 of the book.

In the case of 1 above, it possesses what I call indistinguishability, which amounts to the conversational participants ignoring or not caring about which car Cindy borrowed and hence ignoring or not caring about which of the two relations gets assign to ‘Perez’s car’. It also possesses what I call prospective uniqueness which in the case of 1 amounts to the prospect of there being a unique semantic value in context for the possessive. That is, one of the two relations, and hence a unique relation, will end up being the “right” relation to assign to the possessive depending on which car Cindy in fact borrowed.

3:16: Does your approach have indirect application to other philosophical puzzles, such as vagueness? And does it also indirectly (or even directly) add to our understanding of what a context is and does in terms of semantics or metasemantics generally?

JK: I am not sure about vagueness, but it does have implications for what I call the metasemantics of contextually sensitive expressions. Many contextually sensitive expressions have context invariant meanings that don’t by themselves secure semantic values for them in context. Deictic pronouns and (simple and complex) demonstratives are examples. If out of the blue I say ‘He is smart.’ and give no indication of who I am talking about, it seems as though ‘he’ has no semantic value in context. So ‘he’ has to be supplemented in context in some way for it to secure a semantic value in context. Similar remarks apply to possessives, tense, ‘only’, ‘ready’ (in ‘Rebecca is ready.’), gradable adjectives, demonstratives, modals and more. I call these expressions supplementives to highlight their need for supplementation in context to secure semantic values. I call an account of how a supplementive must be supplemented in context to secure a semantic value a metasemantics for the supplementive. I have defended a metasemantics for supplementives that I call the coordination account:

The Coordination Account Metasemantics (CA)

The semantic value of a use of a supplementive σ in context c is the entity o that uniquely satisfies each of the following conditions: 1. the speaker intends o to be the semantic value of σ in c; and 2. a competent, attentive, reasonable hearer who knows the common ground of the conversation at the moment the speaker makes her utterance and who has the properties the common ground attributes to the audience at the time of utterance would know that the speaker intends o to be the semantic value of σ in c.

(In describing the speaker’s intention in condition 1, I am using the description we as theorists would give of the speaker’s intention. The speaker herself wouldn’t describe it this way. In the context of utterance, she would say that she intends to use σ to talk about or refer to o.)

This is all fine and good, but in cases of felicitous underspecification, a supplementive gets associated with a range of candidate semantic values in context. So we need a metasemantics that explains how supplementives get associated with ranges of candidate semantic values in context. CA doesn’t do that. But I clam a generalization of CA does:

The Generalized Coordination Account Metasemantics (GCA)

The use of a supplementive σ in context c is associated with the range (set) R of candidate semantic values in c that uniquely satisfies each of the following conditions: 1. the speaker intends R to be the range of candidate semantic values associated with σ in c; and 2. a competent, attentive, reasonable hearer who knows the common ground of the conversation at the moment the speaker makes her utterance and who has the properties the common ground attributes to the audience at the time of utterance would know that the speaker intends R to be the range of candidate semantic values associated with σ in c.

The key thing here is saying what it is for a speaker to intend a range R of candidate of semantic values to be associated with σ in c. I claim it is for the speaker not to intend that any individual member of R be the semantic value of σ in c and in using σ in c to intend to convey information about all of the members of R and nothing else. That is, it is for the speaker in using σ to intend to convey information about the members of R and nothing else and not to intend to convey information about any one of them by itself. In such a case, we can think of the speaker’s intention as ruling out everything except the members of R as candidate semantic values for σ in c. The speaker’s intention in such a case is indifferent as to whether any member of R is the semantic value of σ in c but rules out everything else as σ’s semantic value in c.

So the phenomenon of felicitous underspecification requires one to extend whatever one’s metasemantics for supplementives is to a metasemantics that is capable of associating ranges of candidate semantic values in context with supplementives (GCA) rather than unique semantic values in context (CA).

Another topic felicitous underspecification sheds new light on is an issue concerning quantifier domain restriction. A sentence like

2. Every student passed.

can be used in context to convey a claim in which the quantifier ranges over a domain more restricted then the set of students. Perhaps it is used to convey in context the claim that every student in Philosophy 420 at Rutgers in fall 2024 passed. Let’s suppose that in such cases this proposition is semantically expressed by the sentence in context. Imagine that it does this by its LF having a slot in it so that taken out of context the LF expresses a structured proposition-like content with a slot that a property can fill in context, which then further restricts the quantifier. So taken out of context, 2’s LF expresses a proposition-like content with a slot as in 2a and taken in context a property fills the slot and we get a proposition as indicated in 2b:

2a. [Every x: student x ^ ____ x] [passed x]

2b. [Every x: student x ^ in Philosophy 420 at Rutgers in fall 2024 x] [passed x]

On this view, quantifiers are contextually sensitive and get assigned properties further restricting the quantification as semantic values in context. Many philosophers have noted that there are bound to be cases in which there is no unique property that gets singled out to be slotted into things like 2a in context. In the present case, suppose that Philosophy 420 at Rutgers in fall 2024 is also the only upper division class I taught in fall 2024 and that this is common ground. Imagine 2a occurring in a context in which the following three properties are candidates to be slotted into 2a in context with no mechanism singling out a unique one: being in Philosophy 420 at Rutgers in fall 2024, being in Jeffrey King’s upper division class in fall 2024, and being in Philosophy 420 that Jeffrey King taught in fall 2024. Philosophers have wondered what gets asserted in cases of this sort and how the common ground is updated. Call this the problem of incomplete quantifiers.

I claim that these are simply cases of felicitous underspecification, where the quantifier qua supplementive is underspecified. In the present case, the three properties mentioned are the candidate semantic values in context for the quantifier qua supplementive and so the candidate propositions for 2 in context are:

2b. [Every x: student x ^ in Philosophy 420 at Rutgers in fall 2024 x] [passed x]

2c. [Every x: student x ^ in Philosophy 420 that Jeffrey King taught in fall 2024 x] [passed x]

2d. [Every x: student x ^ in the upper division class Jeffrey King taught in fall 2024 x] [passed x]

In the present case, 2b-2d update the context set in the same way and so we have what I call in the book a doesn’t-matter update, where conversational participants are free to update with any of 2b-2d. In the book, I argue that we get doesn’t-matter updates in some cases of felicitous underspecification with all supplementives. However, I also show that we get cases of felicitous underspecification involving quantifiers where the candidate propositional updates in context for the relevant sentence do not update the context set in the same way. In some such cases FUU delivers an update that is the conjunction of candidate propositions in context as the propositional update and in others FUU delivers an update that is the disjunction of candidate propositions in context. This is particularly striking since such examples have not appeared in the literature before. So viewing the problem of incomplete quantifiers through the lens of felicitous underspecification led to the discovery of new sorts of examples. Finally, I wish to stress that in cases of felicitous underspecification involving quantifiers qua supplementives, they behave just as other supplementives do in yielding three kinds of updates in different cases: doesn’t-matter updates, conjunctive updates and disjunctive updates. This looks to be a satisfying resolution of the problem of incomplete quantifiers. This is all discussed in my paper ‘Quantifier Domain Restriction and the Problem of Incomplete Quantifiers’, in The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy of Language, 2025, Ernie Lepore, Una Stojnić (eds.), Oxford University Press.

3:16: Another area in which you’re an expert is the philosophical exploration of the nature of propositions. Frege, Russell and Moore believed in them and many working in Analytic philosophy have also. But some think they are strange metaphysical beasts – too strange to be real in fact don’t they? Can you first set out what the conventional view about their nature is that takes them to be structured entities with individuals, properties, and relations as constituents and why some think that there are problems with how these constituents are bound together and structured coherently? And how the notion of ‘ordered pairs’ was supposed to help answer subsequent puzzles. And perhaps say something about why this is metaphysics and not philosophy of language?

JK: Yeah, some philosophers don’t believe in propositions. I think these days such philosophers are in the minority (but maybe I am in a “pro proposition bubble” and don’t realize how many philosophers don’t believe in propositions). Of course, among those who believe in propositions there are differences of opinion about what they are. Structured proposition theorists from Bertrand Russell (in The Principles of Mathematics) to Nathan Salmon and Scott Soames in the 1980s and 90s thought that structured propositions had objects, properties and relations as constituents. So the proposition that Jeff loves Annie has Jeff, the loving relation and Annie as constituents. These constituents were thought to be held together in some way in the proposition, which is thereby a complex, structured entity. But no one had said much about what it was that held the constituents together and provided the proposition with its structure. In The Nature and Structure of Content (2007, Oxford University Press) I wanted to address this lack. The primary questions I sought to address were: what is it that holds the constituents together in a structured proposition?; and how does the resulting complex represent the world as being a certain way and so have truth conditions?

I think the view of propositions as n-tuples of their constituents arose simply because structured proposition theorists began representing them as n-tuples. I think they probably did this precisely because they had no account of what it is that holds the constituents of a structured proposition together and gives it its structure. So people would represent the structured proposition that Jeff loves Annie as <Jeff, loving, Annie>. In The Nature and Structure of Content, I posed a dilemma for those who employed the structured proposition as n-tuple view. Either they were simply using n-tuples to represent structured propositions or they were claiming that structured propositions really are just n-tuples of their constituents. On the former view, we still haven’t been told what really is holding the constituents of structured propositions together and providing them with their structures. We are just being given a handy way to represent structured propositions and we still need an account of what really holds the constituents of structured propositions together. The latter view, that structured propositions just are n-tuples, struck me as hopeless. How/why would these n-tuples have truth conditions (many n-tuples don’t after all)? I don’t think there is any plausible answer to that question. Finally, there is a Benacerraf-style worry with the view. There seem to be many n-tuples that are good candidates for being the proposition that Jeff loves Annie, with no principled reason for distinguishing one as the proposition that Jeff loves Annie:

<Jeff, loving, Annie>

<Jeff, Annie, loving>

<loving, Jeff, Annie>

<Jeff, <loving, Annie≫

<loving, <Jeff, Annie≫

Finally, as to whether this is metaphysics or philosophy of language, I think it is at the interface of those two fields. What makes it metaphysical to me is that we are trying to say something about the nature of structured propositions—we are trying to say what structured propositions are. That feels like metaphysics. On the other hand, the claim that sentences in contexts express structured propositions is a claim in the philosophy of language.

3:16: You came up with an account that resolved the problem of accounting for the nature of propositions that had so puzzled Frege, Russell and early Wittgenstein and made clear that the ‘ordered pair’ solution was no solution at all. Is it your view that propositions are facts? Can you lay out for us your claim and why it answers the puzzles? And what kind of facts are they - facts about language, about thought – are they abstract facts?

JK: Yes, I think propositions are facts. I call any collection of objects, properties and relations possessing a property or standing in a relation a fact. So, for example, me standing in the loving relation to my wife Annie is a fact. Above I mentioned that what structured proposition theorists need to explain is what binds the constituents of propositions together and gives the proposition its structure and why these complexes have truth conditions. I think the constituents of propositions are held together by a relation that is built out of the syntactic relation that obtains between the words in the LF of the sentence expressing the proposition and the semantic relations between the words in the sentence and their semantic values in context. So, the proposition that Rebecca swims is the following fact, where R is the syntactic relation that obtains between ‘Rebecca’ and ‘swims’ in the sentence ‘Rebecca swims’: there is a context c and there are lexical items a and b of some language L such that a has as its semantic value in c Rebecca and occurs at the left terminal node of the syntactic relation R that in L encodes the instantiation function and b occurs at R’s right terminal node and has as its semantic value in c the property of swimming. This is a fact because it is Rebecca and the property of swimming standing in a relation.

To say that R encodes the instantiation function in L is just to say that in L, R tells us that ‘Rebecca swims’ is true iff Rebecca instantiates the property of swimming. Note that there is a possible language (perhaps not a possible human language) in which ‘Rebecca swims’ is true iff Rebecca fails to instantiate the property of swimming. In this language R encodes the “anti-instantiation function”.

Why is the proposition that Rebecca swims true iff Rebecca instantiates the property of swimming? Call the relation that binds together the constituents of a proposition the propositional relation. Then the proposition that Rebecca swims is true iff Rebecca instantiates the property of swimming because we interpret the propositional relation of the proposition that Rebecca swims as encoding the instantiation function. It inherits this interpretation from the syntactical relation R that it is built out of. A radical feature of my view is that it is something that we do (interpretating the propositional relation in a certain way) that endows propositions with truth conditions.

This version of my view makes propositions very fine-grained. Any two sentences of the same or different languages that differ syntactically express different propositions. In ‘On Propositions and Fineness of Grain (Again!)’ (Synthese 2019, 196 (4), 1343-1367) I defend a slightly different version of my view on which propositions are significantly less fine-grained. I actually prefer this version of my view, but it is harder to explain so I went with the simpler version here.

You also asked me about rival theories of propositions such as the views of Scott Soames and Jeff Speaks and what I thought was wrong with them. I don’t think I have the time and space here to spell out their theories in the detail they deserve and then give my arguments against them. But I refer readers interested in these questions to the book on propositions Soames, Speaks and I co-authored (New Thinking AboutPropositions, 2014, Oxford University Press). Part 3 Chapter 7 comprises my critique of Soames’s and Speaks’s theories of propositions.

3:16: You’ve examined Stalnaker's "two dimensional" account of the necessary a posteriori on which there is no single proposition that is both necessary and a posteriori, (For a (metaphysically) necessary proposition is true in all (metaphysically) possible worlds.) and in particular his argument that concludes that there can’t be any metaphysically impossible worlds. First can you fill in the argument Stalnaker uses to reach his conclusion – and maybe make clear what is meant by a metaphysically impossible possible world?

JK: Yes, you are referring to my paper ‘What in the world are the ways things might have been?’ that appeared in a symposium on Stalnaker’s book Ways a World Might Be (henceforth WWMB-- Philosophical Studies, 2007, 133). Just as a metaphysically possible world is a way the world could have been, a metaphysically impossible world is a way the world couldn’t have been. A world may be metaphysically impossible because according to it, water isn’t H2O, or according to it 2+2=5, or according to it both P and ~P for some proposition P.

It is actually hard to say what Stalnaker’s argument in WWMB is for the claim that there are no metaphysically impossible worlds. In the beginning of Chapter 3, he says they are “too much to swallow”. Though Chapter 3 extensively discusses impossible worlds, the discussion takes the form of a dialogue between two fictional philosophers: Louis and Will. While I think Stalnaker is sympathetic to Louis (who argues that there aren’t any impossible worlds), it isn’t clear how much of Louis’s thinking can be attributed to Stalnaker. I discuss Stalnaker’s view that there are no impossible worlds more below.

3:16: You think he’s wrong don’t you. Can you take us through your thinking here that undercuts his view?

JK: Yes, I think Stalnaker is wrong to deny that there are metaphysically impossible worlds. So let me explain why I believe there are impossible worlds. Given that you accept possible worlds, as both I and Stalnaker do, whether you can plausibly deny that there are impossible worlds can be very much influenced by what you think possible worlds are. For example, suppose you think possible worlds are sets of propositions. Then it looks like it will be very hard to deny that there are metaphysically impossible worlds. For there are sets of propositions that contain metaphysically impossible propositions or propositions whose conjunctions are metaphysically impossible.

Now Stalnaker and I are both actualists: we hold that only one possible world is actual and that to exist is to be actual. That means that if we accept that there are merely possible worlds, they, like everything else that there is, must be located in the actual world.

I think that (merely) possible worlds are uninstantiated properties that the world might have had and which are highly complex and contain other properties and relations as parts. Consider worlds according to which bachelors exist. That means that if these worlds/properties had been instantiated, bachelors would have existed. This in turn means that these worlds/properties have the bachelor property as a part. The bachelor property is itself the conjunction of the properties of being adult, being male and being unmarried (and perhaps others). In saying this, I assume that properties can be combined conjunctively to form conjunctive properties. The big, complex properties that are merely possible worlds result from properties and relations (and individuals) combining in the ways that complex properties and relations generally can be formed out of simpler ones (and individuals). The required modes of combination are things like conjunction, disjunction, negation, existential quantification and so on. Given this, it is hard to see how properties and relations could not combine in a way that results in a complex property or relation that can’t be instantiated. For example, it seems that the property of being gold could conjunctively combine with the property of having the atomic number seventy eight yielding the conjunctive property of being gold and having atomic number seventy eight.

These considerations suggest to me that there are metaphysically impossible worlds: large complex properties that the world could not have had because they couldn’t have been instantiated. As with metaphysically (merely) possible worlds, they exist uninstantiated in the actual world. Now if some of these metaphysically impossible worlds are epistemically possible (roughly, they can’t be ruled out a priori), then we need evidence to rule them out. Worlds in which water isn’t H2O appear to be of this sort. But then it appears there are necessary a posteriori truths: truths that are true in all metaphysically possible worlds but that go false in some epistemically possible but metaphysically impossible worlds. And when we look at the alternative possibilities that rational agents distinguish between in inquiry and deliberation, which Stalnaker frequently encourages us to do, it does seem that they include impossible worlds. In inquiring as to what water is, rational agents distinguished between alternatives in which water is H2O and those in which it is something else. But the latter alternatives are metaphysically impossible. Similarly, in inquiring what a (leather) jacket is made of, a rational agent might distinguish between alternatives in which it is leather, pigskin or faux vegan leather. But once again, the latter two are metaphysically impossible worlds.

In any case, given that my commitment to possible worlds commits me to impossible worlds because of the way I think of possible worlds, I challenged Stalnaker to explain why his commitment to possible worlds qua properties doesn’t commit him to impossible worlds qua properties. In his response to me Stalnaker agreed that this is a good question and to answer it he said he needed to say more about his conception of properties generally, including possible worlds qua world properties. The crucial point is that Stalnaker has a very coarse-grained conception of properties in general, including world properties (possible worlds). On this conception, properties are individuated by what they might apply to. He concedes that on his conception of properties, there will be a world property that can apply to nothing, and so an impossible world, but there will be only one of them. Hence, this leaves Stalnaker’s two-dimensionalism, on which there is no one proposition that is both necessary and a posteriori, in place.

So to determine if there are necessary a posteriori propositions and many distinct metaphysically impossible but epistemically possible worlds for them to go false at, as on my view, or no necessary a posteriori propositions and only one metaphysically impossible world, as on Stalnaker’s view, one would have to adjudicate between our views of properties. One would have to defend my fine-grained structured view of properties or Stalnaker’s coarse grained view. As I indicated above, I think it is a point in favor of my view that the alternative possibilities rational agents distinguish between in inquiry and deliberation seem to include lots of distinct metaphysically impossible but epistemically possible worlds.

As Stalnaker notes, the dispute between us regarding structured fine-grained properties versus unstructured coarse-grained properties is strikingly similar to the dispute between us regarding structured fine-grained propositions versus unstructured coarse-grained propositions. I would refer the interested reader to my paper ‘Unstructured Content’ in Unstructured Content, 2025, Peter van Elswyk, Dirk Kindermann, Cameron Domenico Kirk-Giannini, and Andy Egan (eds.), Oxford University Press for my most recent thoughts on the latter dispute. I hasten to add that though I criticize Stalnaker in the paper being discussed and elsewhere, I have the utmost respect and admiration for Stalnaker and his work!

3:16: Another issue you’ve examined in the notion of anaphora and in particular the puzzles about anaphoric pronouns that cannot be understood as referring expressions that inherit their referents from other referring expressions, nor as variables bound by quantified antecedents. So can you say what anaphora are and what is philosophically interesting about these types of pronouns?

JK: I’ll stick with pronominal anaphora and the pronouns ‘he’, ‘she’ ‘it’ and ‘they’. Very roughly, an anaphoric pronoun is a pronoun whose interpretation is dependent on a previous expression in the discourse in which the pronoun occurs, called the anaphoric pronoun’s antecedent. As you say, in some cases this is because the anaphoric pronoun inherits its referent from a prior referring expression as in one reading of the following sentence:

3. Rebecca is here and she wants to talk to you.

On one reading of this sentence, ‘she’ is anaphoric on ‘Rebecca’ and inherits the referent of ‘Rebecca’ and thereby refers to Rebecca. In another kind of case, an anaphoric pronoun has as its antecedent a quantifier and is functioning as a variable bound by its antecedent, as in one reading of the following sentence:

4. Every male professor admires the students he gave A’s to.

Here on the reading where ‘he’ is anaphoric on ‘every male professor’, ‘he’ appears to function just like a bound variable in first order logic, so that the sentence means that for every male professor x, x admires the students x gave A’s to. Since we have a pretty good understanding of how bound variables work in logic, we have a pretty good understanding of how ‘he’ is functioning in the above sentence. Now if pronominal anaphora always was either a matter of picking up a referent from its antecedent as in 3 or being bound by its antecedent as in 4, philosophers and linguists probably wouldn’t be very interested in anaphora. After all, it is pretty well understood how the pronouns in 3 and 4 are functioning.

What got philosophers and linguists interested in anaphora was the realization that some pronouns with quantificational antecedents aren’t happily understood as picking up a referent from their antecedent or being bound by it. I’ll mention three sorts of cases. First, cases of discourse anaphora: cases in which a pronoun has as its antecedent a quantifier in another sentence:

5. A man walked into a bar. He sat down and ordered a beer.

6. Few professors came to the party. They had a good time.

There are at least two reasons for thinking that the pronouns in 5 and 6 are not bound and both were noted by Gareth Evans. First, it would get the truth conditions of examples like 6 wrong. It would predict that both sentences of 6 are true iff few professors came to the party and had fun. That is incorrect. Second, it would predict that the following sentence is fine and is true on the reading where ‘them’ is anaphoric on ‘no sheep’ iff no sheep are such John bought them and Harry vaccinated them:

*7. John bought no sheep. Harry vaccinated them.

Again, that is incorrect. Second, there are cases like the following Geach discourse adapted from the analogous conjunctions in Geach’s paper ‘Intentional Identity’:

8. Hob believes a witch blighted Bob’s mare. Nob wondered whether she killed Cob’s sow.

8 has a reading on which it could be true even if there are no witches. So on this reading ‘a witch’ scopes under ‘Hob believes’. Suppose in addition ‘she’ is anaphoric on ‘a witch’. Here ‘a witch’ cannot be binding ‘she’ since it takes narrow scope under ‘Hob believes’ but the second sentence is not in the scope of ‘Hob believes’. Exactly what the truth conditions are of 8 on this reading is controversial.

A third kind of example in which a pronoun has a quantificational antecedent but is not bound by it are so-called donkey sentences:

9. Every farmer who owns a donkey loves it.

10. If a John owns a donkey, he loves it.

On the readings we are concerned with, neither sentence is talking about a particular donkey and so the occurrences of ‘it’ in them cannot be referring expressions. In the case of 9, there is evidence that a quantifier cannot scope out of a relative clause, which is why the following is infelicitous on the reading on which the pronoun is anaphoric on ‘every donkey’:

*11. A man who owns every donkey loves it.

But then ‘a donkey’ cannot be binding ‘it’ in 9. In the case of 10, there is evidence that a quantifier in the antecedent of a conditional cannot bind a pronoun in the consequent:

*12. If John owns every donkey, he loves it.

12 is infelicitous on the reading on which ‘it’ is anaphoric on ‘every donkey’ suggesting that the latter is not binding the former. Further, even if ‘a donkey’ in 10 could scope over the conditional and bind the pronoun, it would give 10 the wrong truth conditions, since 10 requires John to love every donkey he owns.

These three kinds of cases in which pronouns are anaphoric on quantifiers but are not referring expressions nor bound variables attracted a lot of attention from philosophers of language and linguists because it is not at all obvious how there are functioning semantically.

3:16: Why do philosophers worry about these things? After all, some might say that we would be better off just leaving it to the linguists to sort out.

JK: As to why philosophers of language worry about these things, it is simply that we share with linguists an interest in proposing semantic theories for various expressions, especially when it isn’t at all obvious what the right semantic theory for an expression is.

My view of these pronouns is that they are devices of quantification. Ordinary quantifiers like ‘every student’ have a force (universal), a restriction (the set of students) and scope relative to other scope taking elements like other quantifiers, negation, verbs of propositional attitude and so on. I take the pronouns we are looking at to themselves be contextually sensitive devices of quantification. That is, they are quantifiers whose forces, restrictions and relative scopes are determined by features of the linguistic context in which they occur. Consider once again the examples of discourse anaphora mentioned above:

5. A man walked into a bar. He sat down and ordered a beer.

6. Few professors came to the party. They had a good time.

Presumably the two sentences of 5 would be true iff at least once man walked into a bar, sat down and ordered a beer. That is because ‘he’ in the second sentence is an existential quantifier whose restriction is the set of men who walked into a bar. Similar remarks apply to 6 except that its pronoun has universal force and its restriction is the set of professors who came to the party. I call these pronouns context dependent quantifiers, since they are quantifiers whose forces, restrictions and relative scopes are determined by features of their linguistic context. I call the present account of these pronouns the CDQ account. See my paper ‘Anaphora and Operators’ (Philosophical Perspectives vol. 8: Logic and Language; 1994, (ed.) J. Tomberlin, 221-250) for details as to exactly how the linguistic context determines the forces, restrictions and relative scopes of context dependent quantifiers. For the account of how this theory handles Geach discourses and donkey sentences discussed above, see my papers ‘Intentional Identity Generalized’ (Journal of Philosophical Logic 22: 1993, 61-93. Reprinted in The Philosopher’s Annual 1993) and ‘Context Dependent Quantifiers and Donkey Anaphora’ (Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Supplementary Volume, 2004), respectively.

Finally, consider the following discourse:

13. A man broke into Cara’s apartment. John believes he came in through the window.

The second sentence of 13 appears to have two readings. On one reading, it is true iff a man broke into Cara’s apartment and John believes of that very man that he came in through the window. The latter would be the case if John knew a man who broke into Cara’s apartment, say Alan, and believed Alan came in through the window. On a second reading, the second sentence of 13 ascribes to John the general belief that a man broke into Cara’s apartment by coming in through the window. This reading would be true if based on conversations with the police, and having no particular person in mind, John believed that a man broke into Cara’s apartment through the window.

On the CDQ account, these two readings result from the pronoun in the second sentence of 13 qua quantifier taking wide and narrow scope relative to ‘John believes’.

3:16: And finally, could you recommend five books that would help take the reader further into your philosophical world?

JK: There are probably a lot of ways to take this question. I’ll take it as asking what five books have most influenced me. To be clear, that doesn’t mean that I agree with them, (though I do think they are all excellent!). It just means that they had a lot of influence on my philosophical thinking.

Saul Kripke Naming and Necessity

David Kaplan Demonstratives (not a book, but very book-like)

Robert Stalnaker Context and Content

Irene Heim The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases (her dissertation—it had a huge effect on me in grad school along with Hans Kamp’s ‘A Theory of Truth and Semantic Representation’) Angelika Kratzer Modals and Conditionals

That’s five but I have to give final shout outs to H.P. Grice’s Studies in the Way of Words and David Lewis’s Papers in Philosophical Logic

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his third book here, his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Peter Ludlow's 'Wait... What?'

Walter Horn's Hornbook of Democracy Book reviews series

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

Josef Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised