Larry Diamond, Edward B. Foley, and Richard H. Pildes (eds.), Electoral Reform in the United States: Proposals for Combating Polarization and Extremism

Larry Diamond, Edward B. Foley, and Richard H. Pildes (eds.), Electoral Reform in the United States: Proposals for Combating Polarization and Extremism (Lynne Rienner, 2025)

In a useful 2003 primer for those thinking about voting rules, Daniel Horowitz writes, “To evaluate an electoral system or to choose a new one, it is necessary to ask first what one wants the electoral system to do.” No doubt, the goal of electoral systems is to aggregate preferences and produce policy choices from such tallies. But Horowitz insists that no system functions as “a passivetranslation of individual wishes into a collective choice.” Thus, he quite reasonably proclaims (though without producing anything resembling an argument for it) that “our voting rules will always bias the results in one way or another” Voter preferences, he says, “are shaped by the electoral system [and] cannot exist independently of it.”

It follows from this that those who would tinker with voting rules are actually themselves making policy choices and should therefore have a clear sense of their goals: “those objectives that people living in a given society might wish to achieve and those they might wish to avoid.” The edited volume under review here is the result of two years of study by an impressive task force of scholars set up to examine possible U.S. electoral reforms, and it certainly does reflect the authors’ clear understanding of the relationships between electoral goals and outcomes. The included papers are laser-focused on what their authors hope can be quickly achieved to mitigate polarization and extremism, both in the policy proposals made by candidates and elected officials, and in the attitudes of the electorate itself. The Introduction to the book, by its three editors, provides a detailed and well-argued explanation of why the task force believes it is of paramount importance to stem the tide of hyper-partisanship that has enveloped the American electorate.

After noting that support for democracy of any kind has fallen sharply in the U.S. over the past couple of decades, the editors suggest that the main reason for this decline has been polarization. Why would that cause increasing disdain for democratic institutions? The main contention here is that polarization of an electorate thins out the space of mutually supported policies, and so makes a society increasingly difficult to enact generally supported (i.e., centrist) policies, which is asserted to be required by democratic governance. What’s worse, at some point, parties in two-pole jurisdictions can become so distrustful of one another that each will start to believe that any victory by their adversary must have been achieved by cheating. Distrust thus becomes disdain, even hatred.

This is hardly the first book on the dangers resulting from the virulent growth in polarization that has been reviewed in this Hornbook (see, e.g., this and this), but it is the first to be focused exclusively on solutions involving voting rule changes. As indicated above, the authors, exceptional scholars all, have made a strong and well-considered case for the urgency of righting the U.S. ship before it entirely founders. I think, though, that it may be helpful to set forth clearly the premises on which their arguments depend before going on to consider any specific recommendations. Naturally, support for some sort of democracy or other is assumed throughout the book. I agree with the authors on the appropriateness of such an assumption. It is almost universally acknowledged these days that democracy is a good thing for any polity to have. But…why? On my view, if one digs into that question a bit more deeply than any of the articles in this book explicitly does, one may find additional constraints on the sorts of voting rules that it makes sense to advocate.

For example, in his paper “Ballot Structures,” Foley makes a compelling case that partisan (if not necessarily also ideological) extremism in election victors can be mitigated by moving from FPTP, single winner elections to any of several alternatives, which, Foley argues convincingly, are more likely to produce winners that the “median voter” described by Downs in his classic work would support. So we have

- Democracy is good–so we should try to keep it.

- We may well lose democracy in the U.S. if we don’t get more median-voter supportable policies than we are attaining with our current reliance on FPTP elections.

- Voting rules can be changed in ways that will produce more median-voter supportable policies than our current elections produce.

- Therefore, we ought to try to change our electoral rules in the prescribed ways.

I take it that this argument is sound (i.e. the premises are true and the conclusion validly follows from them). But what may not be noticed is that one cannot assume that we will indeed have a democracy if the voting rules are altered in the prescribed manner. First, the proposed alterations might result in something that is no longer authentically democratic–even if they had been implemented with the explicit intent of “saving democracy.” Worse, it’s not clear that we have a democracy now, or that what Foley is working so hard to retain is actually worth saving. For consider: if the main goal is to find policies that the “median voter” will support, we might devise a much more efficient method (presumably involving polling) for finding such “centrist” citizens and then simply let these paragons be in total charge of our policymaking. Now, of course, nobody is proposing anything like that, presumably because it wouldn’t be “democratic.” But why not? What elements must an authentically democratic system have? If one focuses exclusively on overcoming hyper-partisanship so that the U.S. will continue to have elections that are in some sense both meaningful and effective, we must believe both that fairly recent U.S. elections have had those virtues and that the new rules will yield plebiscites that will continue to have them.

It will be objected that questions of the type I ask above are precisely where (sensible) political science falls off the cliff into the abstract swamp of political philosophy, but I don’t myself see why the latter pool must resemble quicksand. I have tried to make the case elsewhere that Approval Voting is a good method both for retaining the intrinsic merits of democracy where single-winner elections are called for, and for producing less extreme winners than FPTP elections do. Here, however, perhaps because the task force members are fond of both RCV and party strengthening, Approval Voting isn’t mentioned even once. On the other hand, in his contribution, Foley makes a compelling case for state experimentation with various options (he is particularly drawn to a top-3 method that he likens to what takes place on the TV show Survivor himself) so maybe it’s consistent with his approach that AV also gets an opportunity in North Dakota or Rhode Island.

Foley’s Condorcetian approaches are favored because of their expected nudging toward voter and candidate centrism, and they are argued to be effective in a variety of environments. But Foley does not here consider whether any of his proposals would either create or leave us with authentically democratic decision-making. Rather, his goal seems to be much more narrow: to suggest rule changes that will make elections (and in the case of the U.S., the certification of winners) less bellicose, more like they were a generation or two ago. And it is hard to argue against the claim that if plebiscites are not made to go more smoothly, the country simply cannot be governed democratically…whether or not it ever has been so run. I suppose one could call it a MAEOKA program [‘Make American Elections OK Again’] an initiative with the desideratum of getting both the electorate and the ability to govern back to a place where those who were relatively satisfied with what we had in, say, 1980, can get on with their lives again without having to deal with attempted coups (and a lot of name-calling on the internet).

It’s not that the editors of this volume are blind to past shortcomings in the American system. But they decided it was an inappropriate time and place to discuss the well-known evils of gerrymandering, the Electoral College or the Senate (which they call “the most undemocratically structured legislative chamber of any among modern democracies”) because of the “constitutionally embedded nature of these institutions.” I do not suggest that they ought to be criticized for confining their analyses and proposals to a subset of perceived flaws in the American scheme, but I do want to suggest that other, undiscussed defects in our procedures may bear a significant share of responsibility for the polarization with which they are so concerned, and, I’d add, those defects may also have contributed significantly to the disinterest so many American citizens have in voting at all. For, of course, if nobody votes, neither “top 3” nor RCV will be capable of stemming the tide of virulent partisanship.

It’s important to note, not only that not every author here is one of the three editors (Lee Drutman proposes a more far-reaching reform–one that Pildes here criticizes–that is aimed at some of the problems that existed back in 1980 as well as those around today), but also that Foley seems to have attempted to address some of the criticisms I make above in a new paper called “The Real Preference of Voters: Madison’s Idea of a Top-Three Election and The Present Necessity of Reform.” In addition, Drutman has responded to some of Pildes’ objections to his favored proportional representation both in his Substack and in a piece co-authored by Jesse Wegman in The New York Times. And that article, in turn, has been criticized by Foley here (mostly for addressing only House and state legislative elections, while leaving Presidential and Senatorial elections as they are). Because of the centrality of this continuing debate, in the interest of space, I will focus on that colloquy only and ignore the included papers on Presidential primaries, by Robert G. Boatright, on campaign finance, by Ray La Raja, and on Presidential nominations, by Pildes and Frances Lee. In defense of these arguably irresponsible omissions, I will mention that in follow-up “deliberative polls”conducted by the task force, the proposals made in all three of the bypassed works are admitted by the editors to have been quite unpopular with poll participants. Nevertheless, I think that each paper in this volume has a number of valuable things to say about the topics it covers.

Drutman’s paper on Proportional Representation reprises many of the themes found in his Doom Loop book, the subject of my inaugural (ugh, how I hate that word these days) review in this Hornbook. One of the main points Drutman wants to make in this paper is that he believes the more marginal changes sought by Foley, Pildes, Lee, Boatright, and La Raja are insufficient to address our current crisis. Drutman insists that the situation in the U.S. is already too far gone for any but dramatic structural changes to make significant headway on the depolarization front. He, too, mostly stays faithful to the study’s prime directive, however: finding ways to mitigate hyperpartisanship through electoral rules. As will be discussed below, in his response to Drutman’s piece, Pildes points out that a number of countries exemplify PR and the multi-party characteristics that Drutman seeks, but are at least as polarized as the U.S. anyways.

In my view, PR is required in any authentically democratic polity whether or not it tends to reduce partisanship. (In my book, I propose a novel use of SNTV to achieve that particular desideratum.) For while majority rule is absolutely essential to democratic government, it is hardly sufficient. Proportionality (conceived in terms of policy perspectives rather than party membership) should simply be recognized as indispensable on its own. As both Mill and Dummett have explained, there are at least two manners in which citizens should have representation, and voice commensurate with numbers is one of them. It is as important as ensuring majority rule.

By failing to engage with this right-to-a proportionate-voice-in-government goal and focusing exclusively on PR’s alleged ability to reduce “affective” (rather than ideological) polarization, I think Drutman concedes too much to his editors. However that may be, the benefits of the existence of more than two parties are itemized and examined. Drutman claims that the addition of parties is analogous to adding more magnets to a field of metal slivers. “[I]f one small magnet moves to an edge, the metal pieces (voters) have other magnets nearby” so they are less likely to be drawn to a single big magnet that has migrated into extremism. For their part, majoritarian systems are claimed to encourage peregrinations to the poles. Drutman notes that while Americans absolutely despise “the other party,” considering it not just wrong-headed but satanic, somewhat ironically, U.S. citizens don’t feel particularly close to their own party either. Instead, they are “alienated from all parties.” It is his view that “with more parties, more voters will find [one] close to their values–and perceive other parties as being less far away. Furthermore, he cites studies according to which, in multi-party jurisdictions, “voters feel warmly toward other parties in their coalition….[and] when coalitions shift…from election to election, the positive feelings remain...after the coalition itself has dissolved.” Thus, bi-polar antipathy can be expected to yield to more moderate team-playing when, instead of “collapsing political conflict into a single dimension” multi-party electorates “multiply dimensions through shifting coalitions and alliances.” Drutman closes his argument by pointing to recent positive assessments of the possibility of combining PR and presidentialism, specifying Costa Rica, Cyprus, Chile, and Uruguay as polities that exemplify success in that endeavor.

As noted above, Richard Pildes (along, he notes, with the assistance of Frances Lee and Larry Diamond) provides representation for those task force members whom Drutman has failed to convince of his theses. In “Why Proportional Representation Could Make Things Worse,” Pildes looks with trepidation on The Fair Representation Act, a 2021 House Bill that would either allow or require every state now having at least two Congressional districts to use a form of RCV to produce multiple member districts. First, Pildes notes the many changes voters would have to get used to, however the PR system is ultimately arranged (open list, closed list, STV, etc.), and the U.S. House would need to grow from its current 435 members to at least 700 members. Moreover, if multi-member representation is merely allowed rather than required, there would be disincentives for states to use it since it would likely force the existing major parties down a power-reducing road.

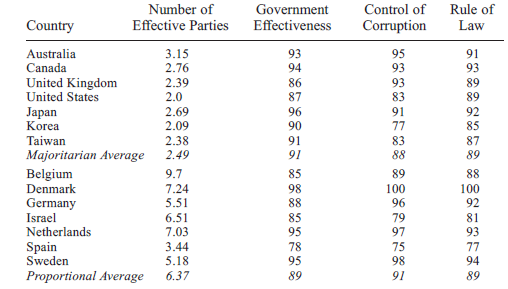

Worse, Pildes denies both (i) that FPTP is actually responsible for the toxic partisanship in the U.S. (since other FPTP countries–like Canada and Australia are considerably more moderate than the U.S.) and (ii) that PR correlates well with more centrist attitudes or policies around the world. In his view, the resulting party “fragmentation” (he uses that term rather than Drutman’s more friendly “multi-dimensionality”) “would make the political process more, not less, dysfunctional.” To show this, Pildes notes that in Western Europe, where there are a number of multi-party democracies in place, “the last decade or so has brought continual dissatisfaction with government….This in turn has generated turbulent politics across much of the continent, including the rise of ‘anti-system’ politics and parties in many countries.” It’s also the case that in many of the relevant countries governing coalitions have been very difficult to arrange and have been too fragile to do much for their citizenry. Using metrics developed by the World Bank, Pildes provides the table below to demonstrate that PR systems don’t do any better than majoritarian systems when it comes to “government effectiveness,” “control of corruption,” and “the rule of law.”

Pildes additionally claims that PR would exacerbate the preexisting fragmentation of the U.S. party system, but I must say that, contrary to his assertion that the Republicans are currently worse than Democrats on with respect to fragmentation, the current cultishness of the GOP seems have left it as unified as it is possible for any large party to be. Their motto seems to be a near guarantor of strength through unanimity: If Trump wants it, we all do! Nevertheless, Pildes is concerned that the single-issue focus exhibited by many existing small parties around the world suggests that extremism and resistance to compromise are making politics in PR polities more elitist as well as hopelessly intransigent.

Drutman’s NYT rejoinder with Jesse Wegman repeats a number of his earlier arguments for PR but puts more stress on the nose-holding that many voters must utilize when voting for one or another candidate they dislike, as well as on the uselessness that all but those in “swing districts” may feel when in a voting booth. It also puts more emphasis on what I consider the key point: even if the majority must “rule,” 51% of the populace should not get 100% of the representation. As an example, the authors note that (my home state of) “Massachusetts currently has nine seats in the House. All of them are filled by Democrats, even though more than one in three voters cast a ballot for Donald Trump in November. In an expanded House with proportional representation, Massachusetts would have 13 members, divided into three districts of four or five representatives each.” Even though I don’t have much use either for Trump or for candidates who support him, I heartily agree that this would constitute an important improvement. And in his new Substack piece Drutman makes what I take to be a crucial point that was largely neglected in the task force book: “Throughout the 2024 election, Democrats kept telling me that democracy was at stake. But the more I heard this argument, the more hollow it began to sound. First, I was never clear what Democrats — who were supposedly defending “democracy” — were actually defending, other than a deeply unpopular institutional status quo.” Those who agree with me that the U.S. has NEVER had much of a democracy will likely also join me in being uncomfortable with the incessant pleas that we “Protect our democracy!” and “Don’t let them take it away!” In other words, Drutman is right about the fact that sometimes we miss the water even when the well has always been dry.

I will let Ned Foley have (almost) the last word here, not only because he occupies a position between Drutman and Pildes on the value of PR, but because his new piece on James Madison and Condorcet exhibits increased attention on the features electoral procedures absolutely must exemplify to be authentically democratic. Foley’s main interest is to demonstrate that in a letter to George Hay written in 1823, Madison can be seen to have evolved to the point where he came to agree on the virtues of a Condorcetian method of picking a winner by “round robin” when no candidate has garnered a majority. According to Foley (and, he says, Madison as well) Condorcet had shown precisely how we should determine an electorate’s preference in such instances. He argues that, for good or ill, we are stuck with most of the creaky Madisonian system of checks and balances that failed even to keep someone who attempted a coup from the Presidency. But, he argues, if we follow Madison’s development and endorse Condorcetian run-offs, we can make things significantly better. With something like a top-three Condorcetian system in place, factors other than the fear of a primary fight against a more extreme party member might carry at least some weight among those who must vote for the acquittal or conviction of an impeached office-holder who has clearly committed treasonous acts.

While I agree with the centrality to democracy of determining what the people actually want, I argue in Chapter 7 of my book, the Condorcetian method Foley advocates may not get us representatives who are wanted by a single voter. In my view, such a system is unacceptable. That is, we must not aim at “This person is better than each of the others,” but instead try to reach “This choice alone is acceptable; the others are not.”

Obviously, attempting to get voting rules right involves complicated and controversial processes, both theoretical and practical, but, sad to say, wherever one’s views on these matters settle, it may well already be too late for the U.S. either to stay or to finally become an authentic democracy. But whatever the practical prospects for the future of democracy in today’s rancour-filled America may be, this book makes valuable contributions to untangling the central issues involved.

About the Author

Walter Horn is a philosopher of politics and epistemology.

His 3:16 interview is here.

Other Hornbook of Democracy Book Reviews

His blog is here