Meritocracy Rules

'The only just distribution is merit-based. Meritocracy thus embraces a plausible and widely-endorsed (in word, if not always in deed) egalitarian idea: equality of opportunity. But it rejects egalitarian distributive rules, as they fail to recognize merit. On the other hand, many libertarians are driven by an affection for personal responsibility. Meritocrats are too—but we argue that a society, like Nozick’s, in which the children of the wealthy have enormous advantages, and people become rich and powerful for reasons other than merit, is not a responsible one. Meritocracy takes personal responsibility more seriously than libertarianism does. '

' Justice is my main topic of inquiry. I wish to know what a just society looks like, and that requires some understanding of the concept of justice, and how it relates to other moral ideals that may arise in the economic context. Do other ideals exist? If so, are they subsumed by justice? Are they competitors to it?'

'Inheritance must be hugely curbed, if not proscribed. This is for many reasons. Most obviously, inheritance interferes with equal opportunity. Having access to undeserved wealth gives you a leg up on your peers. And the income it generates for you (interest, say), is likewise undeserved: It does not reflect your merit. (It reflects your ancestors’ merits.) Inheritances are often not in the interest of those who receive them. Andrew Carnegie warned that inheritance “deadens the talents and energies of the son, and tempts him to lead a less useful and less worthy life than he otherwise would”.'

Thomas Mulligan works on economic justice and group decision-making. Here he discusses the competing philosophies of egalitarianism, liberalism and meritocracy, what's wrong with libertarianism and Nozik, what's wrong with egalitarianism and Rawls, the relationship between meritocracy and justice, why philosophers have largely ignored meritocracy, the relationship between desert and merit, the difference between luck-egalitarianism and desert based justice, the politics of meritocracy, why Rawls argues explicitly against meritocracy, the meritocratic approach to taxation, meritocratic social programmes, how to incentivise good people, and conciliationism.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Thomas Mulligan: A teacher. By my senior year of high school, I was restless and academically uninterested, to put it mildly. Our Latin teacher, Joe Roll, would occasionally offer a course on philosophy. I took it on a whim and was hooked. The philosophical method was congenial and the questions we considered in the course were ones which already fascinated me. I remember that we used two texts by Donald Palmer and also read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. There were about six of us in that course. Half went on to major in philosophy in college. I knew before I arrived at Tulane what I wanted to study. I have had many jobs subsequently, inside and outside of academia, but philosophy, and thus my teacher’s influence, have been constants.

3:16: You’re a meritocratic philosopher and contrast meritocracy with its two main opponents, the egalitarian and the libertarian. Egalitarian philosophy is represented by Rawls, and libertarianism by Nozick and your go-to guy is Aristotle (and surprisingly maybe Marx). So just to give us the geography of all this can you sketch for us these three positions because you think that your favoured position, the meritocrat, is independent of its rivals but can express what you see as the best bits of them too.

TM: Since the 1970s, the philosophical debate about justice has been dominated by egalitarianism and libertarianism. The exemplars of these two approaches, and their most compelling theorists, are Rawls and Nozick. The core egalitarian ideal is of course equality. Rawls doesn’t demand a strictly equal distribution of social goods. That is unattractive for several reasons. He allows for inequalities in these goods if, and only if, they redound to the worst-off members of society. This is his difference principle. The basic idea is that by allowing some inequality in our society we can incentivise people to produce more, and some of that production can be funnelled to the worst-off. This part of Rawls’ theory is consequentialist: When it comes to economic distribution, what matters is how the worst-off will be affected. The core libertarian ideal is liberty.

Nozick advances a minimal state in which people have capacious economic rights. People are free, for example, to contract however they want. If a business owner wants to hire on the basis of race, he is free to do that and it would be unjust for the state to interfere. It does not matter whether the chosen applicant is the most meritorious or not, nor how the hire will affect the worst-off members of society. Further, taxation and other forms of redistribution are ruled out as rights-violations. In contrast to Rawls’ theory, Nozick’s is fully deontological. And then there is meritocracy, whose core ideal is merit. Unlike egalitarianism and libertarianism, it has been unpopular among contemporary philosophers. I am convinced it is correct.

Meritocratic justice consists in two principles. First, there is equality of opportunity. A person’s upbringing should not affect his social and economic prospects. Assuming that they have the same natural traits and they make the same choices, a child raised in poor family and a child raised in a rich family have the same socioeconomic outcomes in a meritocracy (unlike in the actual world). The state is not only allowed but is obligated to establish equal opportunity—through, for instance, public education and taxing inheritances. The second meritocratic principle is that social goods should be distributed on the basis of merit alone. Like Nozick and unlike Rawls’ difference principle, this is a deontological distributive rule. It is a happy side-effect that meritocratic distribution promotes good outcomes, but it is only a side-effect; it is not relevant to justice.

Unlike Nozick, those who distribute social goods are not at liberty to distribute them however they like. They cannot justly distribute them on the basis of race, or gender, or appearance, or sexual tastes; they cannot justly distribute them to friends or family. The only just distribution is merit-based. Meritocracy thus embraces a plausible and widely-endorsed (in word, if not always in deed) egalitarian idea: equality of opportunity. But it rejects egalitarian distributive rules, as they fail to recognize merit. On the other hand, many libertarians are driven by an affection for personal responsibility. Meritocrats are too—but we argue that a society, like Nozick’s, in which the children of the wealthy have enormous advantages, and people become rich and powerful for reasons other than merit, is not a responsible one. Meritocracy takes personal responsibility more seriously than libertarianism does.

3:16: The political right tends to be libertarian – why do you think Nozick et al are wrong?

TM: First I’ll mention a problem which afflicts both libertarian and egalitarian approaches: They are widely rejected by ordinary, working people. They are rejected across lines of race, gender, culture, and political ideology. By now, this has been well-established empirically, which is to say validated through different research methodologies and replicated. Most philosophers don’t seem troubled by imposing a social order on people who pretheoretically reject it. I am troubled by that. Among other things, I think that public rejection of a theory of justice is good evidence that that theory is wrong. I have already described how libertarianism fails to take personal responsibility seriously. Lack of equal opportunity is also a problem.

Nozick just bites the bullet and says that the state cannot justly redistribute in order to establish equal opportunity. This is theoretically nice but unpalatable. Other libertarians try to accommodate some sense of equal opportunity, in their “left-libertarian” theories. I often find these insufficiently rigorous, or just too theoretically clunky. Libertarian freedom of contract is also wrong. In the United States, we have the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlaws discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, and a few other things. That was a great moral victory, but it is an incomplete one. Race, sex, and gender are salient—but for historical, contingent reasons. They are special cases of a general rule: It is unjust to discriminate on any ground other than merit.

3:16: The Rawlsian left are wrong too according to your position. So what’s wrong with egalitarianism?

TM: Equality is an unsuitable ideal to construct a theory of justice upon. People are not equal, in any obvious way at least, and the tendency of our world is to diversity rather than sameness. It is thus an unnatural basis for political life, a fact which J. S. Mill and Mencius and many others have pointed out. Further, as I have mentioned, people feel that egalitarian distribution is unjust. Rawls’ difference principle doesn’t give people what they deserve. It fails to recognize that those who contribute more to our collective economic life ought to receive more in return.

3:16: You argue that merit is the way we get justice so can you sketch for us your views regarding justice and how a meritocracy sits within your theory – and why is it important to you to make a distinction between an ideal and non-ideal theory?

TM: Meritocracy is a theory of distributive justice. It holds that justice is a matter of giving people what they deserve, and that this happens when there is equal opportunity and people are judged on their merits. It is not (in its current state) a theory of justice across all contexts—to include, say, criminal justice. Meritocracy is utopian—I don’t deny it. But I go to some lengths to explain how the theory interacts with and would transform contemporary political practice. I try, that is, to answer the arguments which “non-ideal” theorists have made in recent years. Among other things, I argue that meritocracy is feasible, and I explain the policy prescriptions that flow from the theory. The latter is important for several reasons, not least that truth of a theory of justice may be determined, in part, from what it would demand of us in practice.

3:16: Why does justice matter so much to your approach – is it grounded in the nature of humans?

TM: Well, justice is my main topic of inquiry. I wish to know what a just society looks like, and that requires some understanding of the concept of justice, and how it relates to other moral ideals that may arise in the economic context. Do other ideals exist? If so, are they subsumed by justice? Are they competitors to it? The answer, in short, is that while there may exist distinct moral ideals which play a role in economic distribution, justice, which is to say giving people what they deserve, is the most important by far. And yes: It appears that human beings have a shared understanding that justice is a matter of desert. It is in a sense baked into our DNA. This is evidenced by the affinity for desert-based justice which we see across lines of culture, class, and more. It has been investigated in evolutionary psychology (by, e.g., Michael Bang Petersen), where it is conjectured to be an adaptive trait, regulating small-scale interaction. It is seen in very young children. It has been studied within neuroeconomics. There is even evidence that non-human primates have an understanding of desert. I devote a chapter of my book to this empirical literature. There are of course nuances to it and it must be interpreted with care. But I find it convincing.

3:16: There’s a history to meritocracy – the Chinese have it embedded in their use of education and exams and the US founders had it back in the day – but you say philosophers now have little regard for it. Why has it been largely ignored do you suppose?

TM: Some of the Founders expressed affection for meritocratic ideals, that is true. How well they embodied those ideals is another matter. Not many found their way into the Constitution. Government jobs were originally doled out via the Spoils System—which is to say, nepotistically. The United States did not have a professional, merit-based civil service until the late 19th Century. Meritocracy is deeply embedded in Chinese culture. You allude to the Imperial Examinations, remnants of which still exist elsewhere in Asia, and really all across the world. India’s civil service examinations, which control entry into the powerful All India Services, are an example. As for why philosophers have been uninterested in meritocracy? I can speculate.

First, the Rawls/Nozick dialectic has dominated the debate about justice. The theories they endorse are clear, theoretically compelling, and natural competitors. While some work within the egalitarian and libertarian traditions, like luck egalitarianism, may be thought of as attempts to incorporate “meritocratic” intuitions, it is rarely put that way. Second, philosophers (and academics broadly) are insular. Most philosophers working on justice have little or no experience in the contexts to which their theories are supposed to apply. They are removed from the moral judgments which “ordinary folk” make about economic distribution. They fail to appreciate how unappealing their theories are to these people, and how strong is the affection for meritocratic distribution. (To their credit, some philosophers, like David Miller and Sam Scheffler, have noted this.) Third, our political polarization does not help. Meritocracy is idiosyncratic. The left will embrace meritocrats’ call for a robust inheritance tax and high top marginal income tax rates (today’s top incomes don’t reflect merit). But it will not like our rejection of affirmative action, nor our broader insistence on strict, merit-based hiring. The right will appreciate the meritocratic ethos of personal responsibility but balk at the policies and spending needed to establish equal opportunity.

In our political climate, a meritocrat is more likely to be twice-branded a traitor than regarded as a sensible centrist. The problem is not entirely that philosophy has become too political (although it has). Meritocracy is simply unfashionable. Fourth, there are practical challenges facing philosophers who wish to pursue approaches, like meritocracy, which are outside the mainstream. If you are an egalitarian or a libertarian, you can build a career with the help of influential scholars within your tradition, as well as institutes and money that wish to support the kind of research you are doing (and, more to the point, the political ramifications it has). Nothing like this exists for philosophers interested in meritocracy or desert more broadly. One must both resist intellectual pressure, from the left and the right, and find a way to sustain one’s research with little support.

3:16: Desert is a key idea to the meritocrat, so can you sketch for us what the relation is between merit and desert – and how does desert lead to the notion of equal opportunity?

TM: The relationship between merit and desert is unsettled. Many philosophers have weighed in on this—me, Owen McLeod, Jeppe von Platz, Louis Pojman, John Lucas, and others. We all seem to have different takes on things. This probably doesn’t matter from the point-of-view of normative theory, but it is conceptually interesting. My view is that merit is the most important desert basis. Perhaps it is the only one. (This is apparently consonant with natural language use: Merriam-Webster defines “merit” as “the qualities or actions that constitute the basis of one’s deserts”.) However, being meritorious is a necessary, not a sufficient, condition for desert. Equal opportunity must have prevailed as well. Meritocracy’s two principles—equal opportunity and merit-based distribution—work in tandem. They need each other to produce a compelling account of justice. The typical metaphor for meritocracy, which is a pretty good one, is a footrace: In a just race, the fastest runner gets the medal (meritocracy’s second principle).

Even so, if that runner had a head start then he does not deserve the medal. For there was no equal opportunity (meritocracy’s first principle). He was meritorious, but not deserving. But if there was an equal starting line, and the medal was awarded to the fastest runner (and not on the basis of race, or appearance, or whatever), then justice was done. The meritocratic argument for equal opportunity is transcendental: (1) People ought to get what they deserve; (2) this is only possible if there is equal opportunity; therefore (3) we ought to establish equal opportunity.

3:16: What’s the difference between luck-egalitarianism and desert based justice – and what do you mean when you argue that desert is never forward looking?

TM: There are many differences between luck egalitarianism and desert-based justice. For example, suppose that Davey is the most meritorious worker at his firm, and he is up for a bonus. He does not get it—it goes to a less meritorious worker instead—because his bosses don’t like his religious views, or his sexual tastes, or his politics, or some other feature irrelevant from the point-of-view of merit. The luck egalitarian has no objection to this, as these involve Davey’s free choices (i.e. this is a case of “option luck”). But the meritocrat does object: Davey deserves the bonus because he is the most meritorious worker. Nothing else matters. That is the meritocratic perspective.

Huub Brouwer and I have a paper in which we explore the luck egalitarianism / desertism difference more generally. We argue that sometimes luck egalitarianism is too stingy, sometimes it’s too restrictive, and it’s insufficiently general. Desertism always fares better. Now, on the idea that desert is never forward-looking: The received wisdom about the concept of desert is that if a person deserves something, it’s on the basis of who she is or what she has done. Desert is backwards-looking. You can’t deserve on the basis of what you might be or do in the future. And I agree with that. But Fred Feldman and Dave Schmidtz have advanced arguments in favor of “forward-looking desert”. I think they misread the cases they adduce; in all of them, the real desert-basis already exists.

3:16: Current income and wealth distribution realities show deep inequalities but you want to avoid saying it's the inequalities that make them unjust don’t you? So can you talk us through how the meritocrat approaches our current situation of extremes of wealth and immiseration. Do we end up in a left politics but with a different base from our current left politics?

TM: More or less. For some people, “meritocracy” has a conservative connotation. In fact, when it comes to public policy, meritocracy is radical. Recall that even Marx endorsed the meritocratic distributive norm—income-based-on-contribution—for his penultimate, “socialist” phase of history. There is nothing intrinsically unjust about inequality. A just world is an unequal one. But a just world is unequal only to the extent that people are unequal in their merits. While there are real differences between people in this regard, they are much more modest than the current distribution of income and wealth suggest. Put differently, the extreme inequalities in the United States today are evidence of injustice rather than injustices in themselves.

Today’s inequalities reflect inequality of opportunity, and people being paid for reasons other than merit. Meritocracy gets you some “left politics”. These include high top marginal income tax rates, enormous state support for education (and children more generally), and an end to inheritance. But meritocracy also rejects, roundly, policies which are fashionable among self-described leftists today, such as affirmative action and reparations. The policies of today’s identity politics – driven left would either fail to fix the unjust inequalities which do exist or exacerbate them. If there is an elite class in the United States which holds an undeserved and disproportionate share of power and wealth—and there is—it should be eliminated, not “diversified”.

3:16: Rawls argues against merit doesn’t he – how do you counter his arguments and what do you see as the main objections to Rawls’s account of justice?

TM: He does. In fact, Rawls is one of the few philosophers who explicitly objects to meritocracy. That said, his objections are sketchy, and it is not clear that they are internally consistent. For example, one of his objections is that meritocracy is insufficiently democratic. But elsewhere he speculates that plural voting, a meritocratic form of governance, “may be perfectly just”. There are many objections to Rawls’ account of justice. I’ll mention two. First, even if one accepts the wisdom of his original position—that it is the proper way to identify the correct conception of justice—it is unlikely to yield the principles of justice Rawls claims. Empirical tests of the original position have been conducted (by, especially, Frohlich & Oppenheimer), and the difference principle is not chosen out of it. Some philosophers have speculated that Rawlsian contractors, in the original position, would in fact choose desert-based justice. That has not been robustly tested, empirically. It’d be a worthwhile project for an empirical philosopher to take on.

Second, Rawls’ radical rejection of desert is unsound. (His argument is variously interpreted: that desert should not play a role in distributive justice, or that no one deserves anything at all, or that the very concept of desert is confused.) His claim, in a nutshell, is that everything that putatively makes us deserving—our intelligence, or efforts, or whatever—are just matters of luck. They originate, Rawls says, in “fortunate family or social circumstances”. If you’re intelligent, that’s either because (1) it’s in your natural makeup, or (2) you were raised in an environment which cultivated it. Either way, you’re lucky to be intelligent, and you can’t deserve on the basis of luck. Rawls is correct that luck undermines desert. If Ann is more talented than Nancy because Ann had rich parents who provided her fancy lessons, Ann’s claim to deserve on the basis of her talent is indeed lessened. But Ann’s natural traits are not matters of luck at all. Quite the opposite: They are metaphysically necessary. In any possible world in which Ann exists, she has those traits. A person is constituted by her natural traits, and they can ground desert-claims. (This is a Kripkean argument about the essentiality of origin.) In a meritocracy, which has robust equal opportunity, differences in economic outcomes result only from differences in (1) natural traits and (2) choices. As a result, outcomes are fully deserved.

3:16: You are interesting as a philosopher because you go into detailed policy ideas that are sometimes not discussed – so you have much to say about taxation for example, a subject we all have an interest in? So how does the meritocrat approach taxation – for example, does she think all unearned income undeserved, how do you think about inheritance, do people deserve economic rents and how do you approach efficient and progressive taxation, for example?

TM: Inheritance must be hugely curbed, if not proscribed. This is for many reasons. Most obviously, inheritance interferes with equal opportunity. Having access to undeserved wealth gives you a leg up on your peers. And the income it generates for you (interest, say), is likewise undeserved: It does not reflect your merit. (It reflects your ancestors’ merits.) Inheritances are often not in the interest of those who receive them. Andrew Carnegie warned that inheritance “deadens the talents and energies of the son, and tempts him to lead a less useful and less worthy life than he otherwise would”. I think it is difficult to be happy and confident if one is not “self-made”. Trump is an example of how things may go awry in this regard. Now, unlike other meritocratic principles and policies, inheritances taxes are unpopular. I think what is going on is this: Because opportunities are now so unequal, parents judge, correctly, that their children will be deprived of the good things in life unless they provide them.

It is a true and lamentable fact that in the actual world a child’s socioeconomic prospects are strongly shaped by his parents’ wealth. But if we had robust equal opportunity that would not be the case. Parents would understand that any inheritance would give their child undeserved advantage, and, perforce, give other children undeserved disadvantage. Parents would refrain out of a sense of justice, and because, as described, inheritance would only undermine their child’s accomplishments, character, and life. Another meritocratic policy is a high top marginal income rate—say, a 90% tax on (the portion of) income over $4 million. The U.S. had such a rate from the 1940s into the 1960s (a time of, not coincidentally, extraordinary economic growth). The justification is that these incomes are (usually) economic rent. They do not reflect merit or contribution to the economy. Think of hedge fund managers who exploit inefficiencies in markets and corporate executives whose pay packages result from nepotism. These incomes are undeserved, and so their recipients have no moral claim to them. And, since they are rents, they can be taxed away without loss of economic efficiency.

3:16: What do meritocratic social programmes look like – and what do they refuse? Presumably any form of affirmative action is out and schooling very important?

TM: You put things slightly too strongly. Suppose an employer notices he’s not getting a lot of applications from members of some group (blacks, say). He might undertake special outreach to members of that group, encouraging them to apply, but then judge all applicants on their merits. That form of affirmative action is probably OK. Nobody cares, anyways. But the crux of affirmative action is preferential treatment and quotas—and yes: That is certainly ruled out by meritocratic justice. It is simply racial discrimination, and any time you discriminate on grounds other than merit you act unjustly. Public education is indeed crucial. Justice requires that the state establish equal opportunity, and that means that (among other things) all children must have access to education equal in quality to that which the very richest families can obtain. This is expensive, but the private and social returns to education are large.

3:16: You argue that people actually are meritocrats but yet we see all over the world popular people of no merit like Trump even though people know he’s a rubbish person. Doesn’t that point to a problem with meritocracy, that even if people agree that justice is about getting your deserts people aren’t all that interested in justice, they really are selfish? And would your idea of a plural voting system, an epistocratic system, with a built-in expanded suffrage and voter competence do anything to prevent democracies voting for such bad people and bad things?

TM: The empirical literature is clear: People are not selfish, deep down. The “Homo economicus” assumption of classical economics is wrong, even if occasionally useful. People are motivated, in economic distribution and elsewhere, by a hard-wired sense of justice. We want people to get what they deserve, even if that comes at some personal cost. Trump was a wild choice, but a comprehensible one. The economic condition of the lower and middle classes has hardly improved over the past four-plus decades. In some respects it has degraded. Wage stagnation is well-documented; intergenerational mobility in the U.S. is among the worst in the developed world; new technologies have helped the rapacious extract new rents; and so on. In the U.S., neither party has delivered significant, let alone radical, change. Further, the left has been not just unsympathetic to working people but actively antagonistic.

Recall Hillary Clinton’s characterization of Trump voters as a “basket of deplorables” (which has to be one of the ugliest phrases, not just stylistically, in recent political memory). Trump commiserated with people, if insincerely, and offered, by virtue of his novelty, the possibility of change. Unsurprisingly, Trump did not deliver that change. And we were lucky to avoid a security crisis where his instability could have been truly dangerous. You ask what can be done to prevent democracies from voting for “bad people and bad things”. Nothing can be done to prevent this. That is simply asking too much of a messy world. That is true for meritocracies and democracies alike.

The relevant questions are: How can we improve things? What can we do to incentivize good people to seek public office and to ward off the fakers? To create more honest and intelligent public debate? I believe that the most important step toward this end is not structural but cultural: cultivating merit as our core value. As for my plural voting system, as I say in the paper I have no idea if it would work better than democracy or not. I adduce a formal model to make the case for plural voting; the democrats adduce their own models. All of these models are violated in myriad ways in the actual world. That does not make them useless, but it does mean that to have any real sense of their effectiveness, you’d have to try them out.

3:16: You’ve discussed disagreements in politics – why do some argue that conciliationism supports egalitarianism – why don’t you agree and how should we understand disagreement in politics ?

TM: Martin Ebeling has an argument along these lines. In a nutshell, he argues that political parties “enrich” voters, such that they should regard each other as equally reliable. It follows, he says, that voters should conciliate on political questions—that is, they should “meet in the middle” in terms of their judgments about these questions. Finally, because democratic decision procedures tend to converge on median positions, these conciliating voters can accept democracy as rational. I don’t think Ebeling’s argument works on its own terms, although it’s well worth engaging with. But apart from that, I think that a key idea is that we are obligated not to influence the political process too much—no matter our competence or good intentions. Although we disagree, so long as we make reasonably independent judgments, we can still make good collective decisions. Many theoretical mechanisms have been adduced for this idea of “the wisdom of the crowd”. But when voters exert influence over others, they create dependence within the electorate and thereby reduce collective political wisdom.

To illustrate, suppose Samantha is a rich donor. She judges, in good faith, that candidate A is superior to candidate B. Samantha can spend her wealth to sway other voters to support A. By doing so, Samantha binds other voters’ judgments to her own, which reduces the effectiveness of the collective decision-making procedure, thereby decreasing the probability that the better candidate (whoever it be) gets chosen. At the same, Samantha’s influence increases the probability that the candidate she personally thinks best—A—is selected. As all of this is transparent to her, by exerting too much influence Samantha acts immorally and perhaps irrationally (if her goal is to install the better candidate, and not merely the candidate that she personally judges to be better). I struggled for some time to express this dynamic clearly. I have a new paper in Social Choice and Welfare which illustrates things via a formal model, which I hope does the trick.

3:16: And for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books you could recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

TM:

If a philosopher is looking to get involved in these debates about merit, meritocracy, and desert, the best place to start is George Sher’s monograph, Desert. That provides all the conceptual foundation you need. Like the rest of Sher’s work, is it exceptionally clear and cogent.

It’s become fashionable to denigrate Rawls. This is a mistake. Political philosophy remains in conversation with A Theory of Justice, more than five decades after its publication, for very good reasons. Now, I think that Rawls is wrong and I give arguments for why that’s the case. But his theory remains compelling—it must be grappled with. That said, no one would cite that book as a model of good style.

Naming and Necessity is. (No surprise, given that it was not written but transcribed from lecture.) Kripke’s work has found application throughout philosophy, and I think it’s relevant to the desert debate.

Although he is lukewarm about meritocracy, David Miller’s Principles of Social Justice makes a number of pro-meritocracy arguments, reprinting his important “Deserving Jobs” and “Two Cheers for Meritocracy”.

Finally, the best recent book on desert I’ve read is Kevin Kinghorn’s The Nature of Desert Claims. Kinghorn makes progress in understanding desert, and he reminds us how rich, and still full of mystery, this concept is.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

Josef Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised

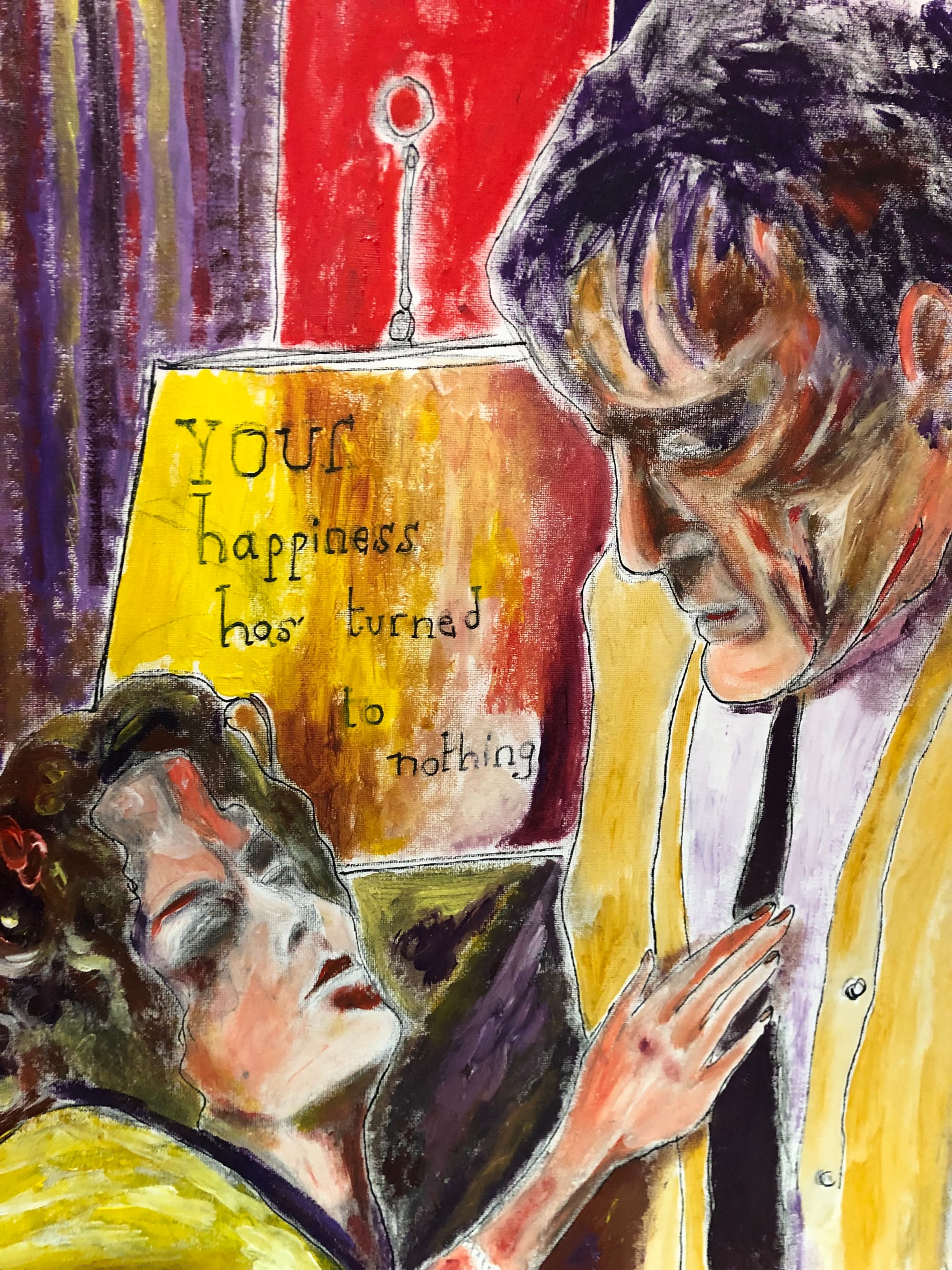

NEW: Art from 3:16am Exhibition - details here