Metaethical Questions

Interview by Richard Marshall

'It’s true that many philosophers view ethics as somehow unique in a way that might make us skeptical of simply applying broader theories of meaning, mind, knowledge, or reality to this domain like any other. I tend to think that the interesting distinction is not between ethics and everything else, but rather between the normative and the descriptive (and possibly other kinds of thought, such as mathematical or modal).'

'My own theoretical leanings are mostly towards some form of pragmatism and constructivism whereby the psychological role of an ethical concept is characterized primarily in terms of a core and normal use in rationalizing intentional action and attitudinal reaction rather than in tracking bits of reality.'

'I believe linguistic treatment of ‘ought’ could usefully expand to cover not just the apparent weakness of ‘ought’ considered as a necessity modal but also cases where modal verbs such as ‘ought’ are not so cleanly treated as operations on propositions because of their prescriptive implications.'

'... a lot of us find something right about Hume’s insistence that there is an important logical-semantic difference between claims about what is the case and claims about what someone ought to do (is-ought gap, descriptive-normative distinction, fact-value divide, etc.).'

'The label ‘expressivism’ is sometimes used in metaethics to mean something like non-descriptivism about normative discourse, which would include my view. But I think this way of using the label obscures important distinctions in accounts of why some areas of discourse are non-descriptive.'

'I’d want to reject the Hume-inspired idea that all attitudes are either cognitive representations of reality or noncognitive pressures on action. (For what it’s worth, I don’t even think this was Hume’s view.)'

'In my view, there are things people ought to believe much like there are ways people ought to act; and both of these ideas relate to normative notions such as reasons and responsibility.'

Matthew Chrisman is a Professor of Ethics and Epistemology at the University of Edinburgh. His research is focused on ethical theory, political philosophy, philosophy of language, and epistemology. Here he discusses metaethics, the four traditional theories, what we mean by ought, how philosophy of language helps with metaethical issues, why he drops a semantics connected to a representational interpretation of the truth conditions in this context, ontological naturalism, deontic modality, issues of cognitivism, Sellars, Brandom, McDowell, Castañeda, knowledge, whether epistemic norms govern belief, truth and belief, whether knowledge and belief are states, and dissent and civil disobedience.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Matthew Chrisman: I remember childhood discussions of religion and faith with my mother and father that sparked interest in questions about the nature of reality and human agency. And I studied philosophical fiction such as Walden Two, Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man and the Wasteland at impressionable moments with inspiring English teachers at my local high school (especially Ms. Strunk). Long rambling discussions with friends at Kentucky’s Governor’s Scholars Program for high school students led me to doubt religion as a way to answer questions about the nature of reality and human agency. In retrospect, this seems to have been a key moment in my becoming a philosopher. I also spent some impressionable time in Tübingen reading German romanticists and idealists, which convinced me of the temptations of a life of the mind. But I was led into the profession of philosophy by top-notch professors such as Eric Margolis, George Sher, and Richard Grandy (as an undergraduate) and Geoff Sayre-McCord, Jay Rosenberg, Dorit Bar-On, Mike Resnik, Jerry Postema, Bill Lycan, and David Reeve (as a graduate student). Their varying ways thinking rigorously about deep and fascinating issues continues to be an inspiration to me.

3:16: You’re interested in metaethics, and use approaches from four domains of philosophy - metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of language and philosophy of mind - to interrogate the nature of ethics from these various perspectives. Can you sketch for us the toolbox you use, and are there any elements of ethics that resist using tools used elsewhere? In other words, is there anything particularly special about ethics that requires us carving out new tools not needed elsewhere?

MC: Metaethics is commonly treated as a subfield of philosophical ethics, but metaethical questions are largely theoretical rather than moral or practical. They are questions such as: Are there ethical properties, and if so what are they like (metaphysics)? How do we acquire ethical knowledge and justify ethical beliefs (epistemology)? What is the best theory of the meaning of terms like ‘good’ and ‘ought’ (philosophy of language)? And what is the nature of moral judgment and how does it motivate action (philosophy of mind/psychology)? Any full metaethical theory has to answer all of these questions and many subsidiary questions. The practice of doing metaethics is largely a matter of balancing theoretical costs and benefits of various claims in pursuit of an overall coherent and satisfying view that addresses these questions.

It’s true that many philosophers view ethics as somehow unique in a way that might make us skeptical of simply applying broader theories of meaning, mind, knowledge, or reality to this domain like any other. I tend to think that the interesting distinction is not between ethics and everything else, but rather between the normative and the descriptive (and possibly other kinds of thought, such as mathematical or modal). Ethical, prudential, epistemological thought is, in my view, distinctively caught up in evaluating and prescribing more than describing and explaining.

And I think this renders some of the standard theories from other domains of philosophy problematic in the normative case in ways that we might not have anticipated had we focused only on the descriptive case. Nevertheless, I suspect we can still use a lot of the same theoretical tools for thinking about the normative case.

3:16: There are four dominant positions that a metaethicist might take: nonnaturalism, expressivism, error theory/fictionalism and naturalism. Can you briefly summarise these four positions and say where you end up and then show how we can now start asking questions about how they might be mapped out via the four philosophical domains? Are there theories that this traditional approach misses out on?

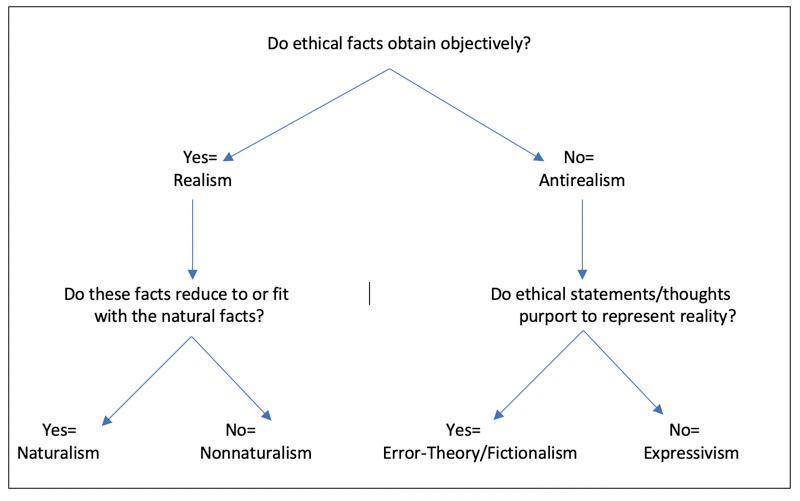

MC: The positions you mention are the four “traditional” theories I cover in the central part of my textbook What is This Thing Called Metaethics? I see them as the four main research programs that emerged in and largely constituted 20thcentury metaethics. There are different ways to slice the pie, but I summarize these theories in the book with a figure like the following.

Chapters 2-6 of the book are where I explain and evaluate the main kinds of answers philosophers in each of these four camps have tended to defend when it comes to questions of metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of language. In chapter 7, I briefly canvass several more recently developed theories that don’t fit so well on the traditional chart, such as hybrid views, response-dependent views, constructivist views, and pragmatist views. My own theoretical leanings are mostly towards some form of pragmatism and constructivism whereby the psychological role of an ethical concept is characterized primarily in terms of a core and normal use in rationalizing intentional action and attitudinal reaction rather than in tracking bits of reality.

3:16: A big metaethical question you’ve looked at is what we mean by ‘ought’. Are there ethical ought issues relevant to the non-ethical ones - for example the distinction between agential and non-agential ought-statements useful in ethics but not reflected in linguistic treatments of the the verb ‘ought’?

MC: The word ‘ought’ is odd, and maybe in ways that are idiosyncratic to English and nearby languages. Grammatically, it is a modal verb, which suggests it should fit into systems of necessity and possibility, and be analyzable in terms of a proposition holding true in various possible worlds. But the word is both more like the necessity modal ‘must’ than the possibility modals ‘might’ and ‘may’ and yet clearly weaker than ‘must’ in the sort of necessity it conveys. Moreover, for more than 200 years, Western philosophical ethics has tended to frame one of its core of questions in terms of what agents ought to dorather than in terms of what propositions ought to be true. I suspect these facts mean that our intuitions about the meaning of this word are highly unreliable, but I still think it important for metaethics to sort out an account of the meaning of the word ‘ought’.

In my book The Meaning of ‘Ought’: Beyond Descriptivism and Expressivism in Metaethics, I sketch an account of what we could mean by the word ‘ought’ that is motivated by the ideas that (i) ‘ought is a weak necessity modal, and (ii) ‘ought’ is used to make ethical claims with prescriptive implications, but (iii) it is also used to make non-ethical claims, some with similar prescriptive implications and some that do not have these implications, yet (iv) in all of these uses we still seem to be deploying the same word rather than homonyms.

My idea, in brief, is to respect these ideas by expanding the standard understanding of a necessity modal. The standard understanding derives from modal logic which treats modals as operators on propositions, modeled in terms of whether that proposition is true in all (necessity) or some (possibility) possible worlds in some stipulated set of possible worlds. For the purposes of metaethics, I suggest this needs to be expanded in two ways. First, in addition to various “flavors” of necessity (e.g. nomological, epistemic, moral), I think we should recognize multiple possible strengths of necessity within each category. This idea isn’t new to me; various linguists and philosophers have been thinking about how to model the semantics of weak and strong necessity for several decades. I make a a proposal for how to do this in the book, but others have made similar proposals that might be better. Second, I think we should mark a difference between uses of modals as operations on descriptive contents (e.g. “James is happy”), and uses as operations on imperative contents (e.g. “James, give money to charity regularly”). This allows me to explain how a “agential” use of ‘ought’ (e.g. “James ought to give money to charity regularly”) differs from a “non-agential” use of ‘ought, (e.g. “It ought to be the case that James is happy”). I’m able to do this in a way that treats ‘ought’ in both cases as the same word and in a way that captures some apparent entailments between ethical ought-claims and imperatives that interest many ethicists. I don’t, however, think the phenomenon of “agential” uses of ‘ought’ is restricted only to ethical contexts. In my opinion, there can be agential but non-ethical uses of ‘ought’. But this agential use is of course especially interesting for ethics.

So, in answer to your question, yes I believe linguistic treatment of ‘ought’ could usefully expand to cover not just the apparent weakness of ‘ought’ considered as a necessity modal but also cases where modal verbs such as ‘ought’ are not so cleanly treated as operations on propositions because of their prescriptive implications. There are a few linguists and philosophers working on how the semantics of agency verbs interacts with the semantics of modals, and there is a burgeoning literature on the semantics and logic of imperatives, but I suspect it is still early days in making sense of all of this. The proposal in my book is very rough and meant mainly to spark further consideration and to urge a holistic approach that takes all three of these phenomena (modal verbs, agency verbs, and imperatives) into account.

3:16: You approach metaethical issues of ought using tools from the philosophy of language, what in the jargon is a ‘truth conditionalist approach to compositional semantics’. For the uninitiated who might be put off by the technical jargon, what is this and why is it so useful?

MC: One of the key facts linguists and philosophers of language want to explain about language is how words combine to form meaningful sentences, such that from a relatively small vocabulary people can produce and understand a very large number of unique sentences. To explain this, what we want is a systematic way to predict sentence meaning as a function of word meaning and the way word meanings are put together according to the grammar of the language. There are various semantic methodologies whose appropriateness depends on what exactly one is interested in explaining; but when it comes to explaining semantic composition (at least for declarative sentences) I think some form of a truth conditionalist semantic framework is the best game in town.

The basic idea is to seek to explain the contribution individual words make to the meaning of sentences in which they figure by trying to articulate precisely and systematically the affect those words have on the conditions under which (declarative) sentences are true. This is a widely used semantic methodology (associated with the likes of Frege, Montague, Davidson, Lewis, Heim, Kratzer, and many many others). There are many reasons linguists and philosophers of language have regarded it as especially useful, but I think one of the central reasons is that part of what we are trying to capture in semantics is competent-speaker intuitions about when one sentence entails another sentence in virtue of their respective meanings; and entailment (at least amongst declarative sentences) is something about when the different sentences would be true — i.e. something about their truth conditions. So seeking to articulate precisely and systematically the contribution words make to the conditions under which a sentence would be true seems apt for capturing these intuitions within an overall account of how a relatively small vocabulary can produce a very large number of unique meaningful sentences.

3:16: Usually this is a semantics connected to a representational interpretation of the truth conditions, but in the case of normativity you drop this interpretation. Again, just so the jargon doesn’t lose the thought for readers, what is this – and why drop it?

MC: The basic sentences the truth conditional semantics was originally built to explain are often naturally thought of as descriptions of reality. For example, “Sally is tall” describes Sally’s height; “Grass is green” describes the color of grass, and so on. Because of this, I think a lot of philosophers find it natural to conceive of the condition under which one of these sentences is true as “a way reality could be” and then more generally to think of articulations of the truth conditions of such a sentence as representations of a way reality could be. This idea is also reinforced by a perennial philosophical theory of truth that says that a sentence is true just in case it corresponds with the way reality is.

My view, however, is that it is a mistake to generalize from these basic cases to all declarative sentences, and I’m dubious of the correspondence theory of truth as a general account of the nature of truth. To begin to see why, consider the sentence “It might rain in Scotland.” One can treat this sentence as a description of reality. Some philosophers might view it as a description of someone’s confidence level; other philosophers might view it as a description of some region of the set of possible worlds. But I’m much more inclined to see it rather as expressing a kind of modulation of confidence levels applied to an embedded description. Nevertheless, it is still the sort of sentence that we want to say is true under some conditions; it entails some sentences and is incompatible with others.

That’s what led me to think that not all articulations of truth conditions are representations of a way reality could be. And when I looked at the details of the way truth-conditionalist semantic theories typically articulate the meaning of sentences like the one above, it doesn’t seem to have a lot to do with representing “ordinary” bits of reality such as people and their heights or plants and their colors; rather it has to do with relations amongst various possible worlds posited as part of an abstract model of meaning. So, while I think one can understand articulations of truth conditions in this case as representations of reality, I think there’s also some philosophical pressure to look for other ways to understand what’s going on when we articulate the truth conditions of more complicated sentences like this one.

That may seem unrelated to metaethical debate about how to account for the meaning of normative sentences, but one of the main goals of The Meaning of ‘Ought’ is to argue that the situation is very similar for ought-sentences. With ‘ought’, we can also generate declarative sentences that seem to be truth-apt and to stand in various entailment and incompatibility relations with other sentences, of precisely the sort that we’d normally expect to explain via articulations of their truth conditions. But, even more so than with might-sentences, I think there is strong philosophical pressure to be at least somewhat skeptical of the idea that ought-sentences describe reality. After all, a lot of us find something right about Hume’s insistence that there is an important logical-semantic difference between claims about what is the case and claims about what someone ought to do (is-ought gap, descriptive-normative distinction, fact-value divide, etc.). This skepticism is why I wanted to stick with the truth-conditionalist approach to semantics but argue that articulations of truth conditions, especially in this case, needn’t always be interpreted as representations of reality.

3:16: You’re an ontological naturalist aren’t you – which means that you reject antireductivist nonnaturalism, a posterirori reductive naturalism, analytic naturalism, error theory and fictionalism. Roughly, you want to posit only stuff that natural scientists would say exists in any theory of normativity – so does that mean that you have to find something else for norms to be doing? So why aren’t you an expressivist given that you don’t think ought statements are descriptive – and does that mean that you are not an epistemic expressivist either?

MC: As I see things, all of the metaethical views you mention except for antireductive nonnaturalism agree that the only stuff in reality is, roughly speaking, the stuff we’d recognize in a scientific explanation of reality. These views just offer different theories of what is going on with normative discourse (e.g. ethical discourse) that are supposed to be consistent with this commitment to ontological naturalism. Expressivists do the same thing, and I see my view as doing the same thing too. So we’re all ontological naturalists except for the antireductive nonnaturalists.

The label ‘expressivism’ is sometimes used in metaethics to mean something like non-descriptivism about normative discourse, which would include my view. But I think this way of using the label obscures important distinctions in accounts of why some areas of discourse are non-descriptive. The expressivist tradition in metaethics running from Ayer and Stevenson to Blackburn and Gibbard and beyond has emphasized a psychological distinction inspired by Hume between cognitive representations of reality and noncognitive pressures towards action. And this tradition has drawn on and contributed to the development of a tradition in the philosophy of language that emphasizes the role language has as the public medium whereby private attitudes are expressed. Roughly speaking then, the central idea in expressivism is that at the most fundamental level, language gets its meaning from the way it can be used to conventionally expresses attitudes; and, more specifically, normative language gets its meaning from the way it can be used to express noncognitive attitudes (such as preference), whereas descriptive language gets its meaning from the ways it can be used to express cognitive attitudes (such as belief).

So why don’t I accept that? Well, at base, I guess it’s because I think this is the wrong way to account for why normative discourse is non-descriptive. In part, this is because I think other areas of discourse (e.g. might-sentences) are also non-descriptive, but it’s not nearly as plausible that these express something like noncognitive pressures on action. I don’t think they are normative, but I want some general framework for making sense of (i) the way that they are truth-apt, but (ii) don’t describe reality. I also think normative sentences can clearly embed in all of the ways that the sentences expressing cognitive attitudes can embed (e.g. in “Sally believes that S” and “Everybody knows that S”), which strongly suggests that normative sentences don’t mainly function to express a noncognitive attitude rather than a cognitive attitude. So I’d want to reject the Hume-inspired idea that all attitudes are either cognitive representations of reality or noncognitive pressures on action; this is a false dichotomy.

But more programmatically, the main reason I don’t consider myself an expressivist is that I’m more attracted to a competing tradition in the philosophy of language associated with people such as Peirce, Sellars, and Brandom that emphasizes instead the role language has in undertaking commitments as part of a shared practice of collectively reasoning about how reality is and what to think, do, and feel about it. According to this tradition, public language, mental attitudes, and collective thinking/discussion are intertwined in ways that make it impossible to fully explain where language gets its meaning in terms of the private attitudes it expresses publicly. We explain meaning instead in terms of the “discursive” or “inferential” commitments undertaken and mutually recognized by participants to a conversation where one makes or accepts various statements. So, if you insist on a label, ‘inferentialist non-descriptivism’ about an area of discourse is my preferred alternative to ‘expressivist non-descriptivism’.

3:16: Here we might look at deontic modality in an extended sense - which is about what is morally or legally or practically obligatory and permissible where these are treated as species of necessity and possibility- Is it through these modal operators that you are able to generate your alternative to expressivism?

MC: I think you can accept the reasons in favor of inferentialist non-descriptivism over expressivist non-descriptivism gestured at in the previous answer without getting into the theory of deontic modality. But one of the strategies of The Meaning of ‘Ought’ was to combine very general ideas about how to explain meaning in a way that allows some declarative sentences to be descriptive and others to be non-descriptive with more specific considerations about the meaning of ‘ought’ considered as a deontic modal. My basic idea there, drawing on deontic logic and the possible worlds version of truth conditionalist semantics, is that modal words such as ‘ought’ are what semanticists call “intensional operators.” What this means is that their semantic function is modeled not like an ordinary predicate, which can be said to hold of some range of objects, but rather as a linguistic device that displaces our consideration from what holds of objects in the actual world to what holds across some range of possibilities.

Again, the example of “It might rain in Scotland” is helpful. It’s not very plausible to think that ‘might rain’ functions semantically as an ordinary predicate, holding of the weather in Scotland just in case it has the property of might-rainness. Rather, relatively standard accounts of this word’s semantic function all treat it an operator, which (roughly speaking) displaces linguistic consideration from the weather in Scotland as things actually are to the weather in Scotland as things possibly could be (given some body of evidence). More picturesquely, in deciding whether to accept this sentence as true, we consider not the actual world but some set of imagined possible worlds consistent with the relevant body of evidence and ask whether the embedded descriptive sentence “It is raining in Scotland” is true in some of them.

I find this “displacing” function of intentional operators highly suggestive for thinking about what ought-sentences are doing if they are neither describing reality nor expressing noncognitive attitudes. The basic idea is that ought-phrases also function not as ordinary predicates do but rather as intensional operators do, displacing linguistic consideration from what holds in the actual world to what holds across some range of possibilities. To be clear, this isn’t meant as an account of what people are consciously thinking about when they process might-sentences or ought-sentences. The idea is that this displacing function is the best way to make sense of the linguistic processing implicit in our production and understanding of these sentences – a way, I’d want to point out, that is part of an overall truth-conditionalist semantics but not committed to the idea that all declarative sentences describe (actual) reality.

3:16: Does your view commit you to a form of cognitivism or non-cognitivism in metaethics – or is there a third way captured by inferentialism? How influential is Sellars in all this – and the Pittsburgh Hegelianism of Brandom and McDowell?

MC: As I suggested before, I’d want to reject the Hume-inspired idea that all attitudes are either cognitive representations of reality or noncognitive pressures on action. (For what it’s worth, I don’t even think this was Hume’s view.) But I think we can separate the notion of a “cognitive attitude” in the sense of the kind of cognition that can partially constitute a piece of knowledge from the notion of a “representation of reality”. Here, I’m inspired by a more Kantian picture which would allow for cognitive thoughts (or “beliefs”) that are empirical representations of possible objects of experience alongside all sorts of other thoughts (or “beliefs”) that are still “cognitive” in the relevant sense but not empirical representations of possible objects of experience. Some of these might be representations of some other aspect of reality, but others might be higher-order cognitions having to do with the conceptual and logical connections between various lower-order cognitions, or partial articulations of the structure of thought itself.

Early on, Sellars was a big influence in my thinking about these things. Although the idiom and dialectic are now outdated in ways that can make it difficult to understand, I think his 1968 book Science and Metaphysics: Variations on Kantian Themes is still worth studying for the way it sought to move beyond a flat-footed Humeanism to a revived Kantianism both in its philosophy of mind and in its metaethics. Chapter 7 of that book played an especially big role in the development of my doctoral thesis. Based on this interest, I’ve also been interested in Brandom’s and McDowell’s work. I don’t know how Hegelian it is, but the idea that ‘ought’ is a modal-normative word that gets its meaning not from what in reality it represents nor from the noncognitive attitude it expresses but from the way it lets us articulate conceptual connections between various factual claims and prescriptions for what to do, think, and feel definitely owes something to Brandom’s way of working out the inferentialist program in his book Between Saying and Doing. More specifically, I like the idea (that he gleans from Kant and Sellars) that modal and normative vocabularies earn their keep, so to speak, from their use to articulate and think about conceptual connections that one must already implicitly appreciate in order to count as competent with other vocabularies; and I think this is nicely amplified by the standard treatment of modal verbs as intensional operators rather than ordinary predicates.

However, the big influence for The Meaning of ‘Ought’ is not so much Kant, Sellars, or Brandom but rather a former student of Sellars’: Castañeda. I think his 1975 book Thinking and Doing: The Philosophical Foundations of Institutions is a neglected masterpiece. In particular, I think he saw better than Sellars that ought-claims need to be treated as truth-apt in a perfectly normal sense, in order to make sense of entailment and consistency relations they stand in with other sentences, but we also need to explain how they stand in inferential connections with prescriptions of the sort expressed by imperative sentences. So, rather than treat normative ought-claims as expressing universalized prescriptions (as Hare did) or we-intentions (as Sellars did), Castañeda argued that we should treat them as sentences whose truth value depends not only on how the reality is but also which norms are applicable. And he offered a very rich theory of how different norms are applicable in different institutions and how this bears on the rational psychology of agents seeking to reason about what to do within those institutions.

3:16: What picture of knowledge of what one ought to do do you ascribe to, and why is it a superior approach to rivals?

MC: There has been a lot of debate in metaethics about whether expressivists can make sense of the fact that we embed ethical sentences under ‘If…” and “believes that …”. This is part of the infamous Frege-Geach problem, and one of the standard expressivist moves is to try to “save the appearances” of propositional form for ethical language while maintaining the idea that ethical statements express noncognitive attitudes rather than cognitive representations of reality. But I think it is just as important to make sense of the fact that we also talk about people knowing what they ought to do. This is one of my main reasons for skepticism about expressivism. I think it means we need to not only save the appearances of propositional form for ethical language but also make sense of (i) full-fledged ethical propositions, (ii) the way belief in them can be reliable and supported by reasons, and (iii) what is to know one of them to be true. This leads some critics of expressivism to argue that ethical thought must be representational just like other thought about how reality is. However, knowing what you ought to do also seems to me to be special in a way that distinguishes it from ordinary knowledge of how reality is. More specifically, there seems to be a distinctive (practically) rationally way to get from that knowledge to actually doing what you know you ought to do. This leads me to think knowledge of what one ought to do is not knowledge of how reality is but rather practical knowledge of what to do across various possible circumstances. The rough idea is that knowing what one ought to do is knowing which prescriptions are validly applicable to which people across a range of possible circumstances. In my way of working this out, this isn’t knowledge of some descriptive fact about reality, but rather a kind of generalized practical knowledge of what one is to do.

3:16: Are there genuine epistemic norms governing belief, and if so where in the vicinity of belief are we to find the requisite cognitive agency?

MC: In my view, there are things people ought to believe much like there are ways people ought to act; and both of these ideas relate to normative notions such as reasons and responsibility. The puzzle here arises if we regard such normative ought-claims as apt only when the person to whom they are applied can exercise their agency in conforming to the implicit prescription. For it seems to me that a lot of our beliefs are automatically formed by cognitive systems, which (thankfully!) operate without much input from our wishy-washy fallible agency. To be sure, we can choose where to look, but once we look, I think we mostly just automatically believe what we see, except in special cases. Also, I think a lot of non-observational belief formation is based on tacit and quick assessment of evidence and heuristics, which is a process highly influenced by factors outside of our immediate control. I’m not sure where to find the requisite cognitive agency, but I’m inclined to think it has something to do with how we choose to inquire and what we do to maintain generally coherent webs of belief. But I also think of cognitive agency and responsibility as something more like a social status we grant each other in well-functioning epistemic communities rather than a psychological capacity we could somehow find within individual minds.

3:16: Do you think that truth isn’t and can’t be the aim of belief and what difference does this make?

MC: I think the idea of belief as having an aim is a misleading metaphor. Sometimes when epistemologists talk about truth as the aim of belief, they seem to mean that truth is the standard of correctness for belief. And I’m more or less happy with that idea. If someone believes something that we think isn’t true, then we think their belief is incorrect. But sometimes when epistemologists talk about truth as the aim of belief, they seem to want mobilize a picture of belief as something like cognitive archery shots which believers aim at the target of truth. For reasons that I think are best explained in Rosenberg’s somewhat neglected book Thinking about Knowing (see ch. 6), I think this picture would make sense only if we had independent grip on where these targets are (i.e. knowledge of what is true that is independent of what we believe). But we don’t have that! Knowing what is true is an instance of believing something to be true. To be clear, I don’t think rejecting the archery picture means that truth is unimportant to inquiry. When inquiring into some topic, I think we should try to acquire knowledge and understanding, and these goals require some correct beliefs. So, assuming truth is the standard of correctness for belief, there’s a good sense in which inquiry aims at truth (amongst other things). I’m just skeptical of some of the imagery evoked by the idea that belief aims at truth.

3:16: Why do some epistemologists want to deny that knowledge and beliefs are states, why do you say they’re wrong and where does that leave you when it comes to trying to answer the relevant questions about the normative evaluation of belief?

MC: If you think there are things people ought to believe like there are ways people ought to act, and you think we can hold people responsible for both, then you might be inclined to think that, in believing, one is exercising one’s agency in a parallel way to how, in acting, one is exercising one’s agency. This line of thought suggests that believing is a kind of mental analog of acting. And since acting is active rather than stative, this might lead you to the view that belief is not a state of mind but rather something the mind does. Alternatively yet compatibly, if you think that believing is somewhat like shooting arrows at the truth, then you might also think believing is an active performance rather than a stative way of being. And, as Sosa has argued, this way of thinking of belief would give us resources for making sense of the way knowledge seems different from and better than luckily true belief.

In my view, however, all of these ideas trade on a category mistake. I’m happy to recognize mental actions such as considering, imagining, reasoning, but as I see things belief is a state of mind, and knowledge is partially constituted by being in such a belief state. This is born out in the way we talk about belief and knowledge using verbs that have grammatical markers for stative rather than active, and it is an integral part of how we normally conceptualize our minds as storing a bunch of non-occurrent beliefs, some of which are knowledge. Now, maybe at the end of the day we should embrace a pure process ontology and throw out all talk of states of mind. But I think doing so would require replacement concepts for belief and knowledge as they function in ordinary discourse as well as current epistemology and philosophy of mind. That is to say that I think process ontology is not already part of our concepts of belief and knowledge, and so we should think of normative evaluation of belief (of the sort that is relevant to determining whether a belief is knowledge) as evaluation of someone’s state of mind rather than evaluation of something they are actively doing. I think this puts pressure on many epistemological theories that construe epistemic justification and responsibility for beliefs along similar lines to ethical justification and responsibility for action.

3:16: And finally, to bring us a bit closer to the ground than the meta-concerns of philosophy, you’ve looked at dissent. So are there ways in which political dissent even when illegal may be justified?

MC: The classic question of civil disobedience was about when it could be justified, assuming that one respects the overall political legitimacy of the law of one’s society, to break the law in protest. There are various answers to this question that I find somewhat attractive, which derive from liberal political philosophy and from deliberative democratic theory. However, I think there’s an important sense in which this is the wrong question to be asking about political dissent, at least right now.

For one thing, there are lots of cases of political dissent that aren’t illegal; and yet we may want to argue that some of them are better than others. For example, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about de-platforming protests, especially of the sort where student activists seek to prevent a controversial speaker from speaking on a university campus. These are typically legal (at least initially) so they don’t fit the classic mold of civil disobedience, but I’m inclined to think some of them are better than others, and not just because I think some speakers shouldn’t get a platform and others should. So we need some way to differentiate better and worse ways of voicing dissent even legally.

For another thing, a lot of political dissent occurs when the political legitimacy of the law of one’s society cannot be not assumed. The pro-democracy and anti-corruption protestors in various repressive regimes around the world typically do not assume that their state’s power to make and enforce laws is legitimate. Moreover, even in the rosiest real-world democracies, there are reasonable concerns about the way things like money in politics, structural racism and sexism, voter suppression, and deal-making between factions threaten to undermine the legitimacy of at least some important swaths of law. But even so, there is still a sensible question to be addressed about how to evaluate ways of protesting those regimes and laws. That is to say, even if we don’t assume the political legitimacy of the law of one’s society (as philosophical discussions of civil disobedience typically did), we can still evaluate protests as better or worse in various respects.

So one of my current projects is to try to understand this dimension of political evaluation. The key and tricky issue is how to prescind from one’s own engaged views about which object of protest are protest-worthy, in order to focus on the question of which of various possible ways of protesting any given object are better and which are worse.

3:16: And for the curious readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

MC: In addition to books mentioned above,

Angelika Kratzer’s Modals and Conditionals

and Paul Portner’s Modality are two books by philosophically inclined linguists that have been very helpful for developing my views about modal verbs.

Huw Price’s Naturalism without Mirrors contains a lot of really interesting essays that have influenced my views about truth and metaethics.

I have also learned a lot from studying Michael Thompson’s Life and Action.

The book I love to teach and think all students of philosophy should study for its methodology as much as its conclusions is Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees