Noble Savage Redux: Rousseau meets the Pirahã

By Peter Ludlow

The escapist philosophers of the eighteenth century conceptualised paradise not as a merely metaphysical refuge from the harsh realities of life but as geographical loci which really existed in some distant parts of the world. Atlantis, the Hesperides and Avalon, blessed isles of plenty, were believed to lay across the western oceans. As some remote areas of the globe had not yet been explored, there was hope, that an earthly paradise would be discovered one day. Seafarers and explorers were expected to bring back the news and tell the world about their encounter with the inhabitants of paradise, happy people living a simple, natural life, Noble Savages, who had preserved all the original qualities, physical and moral, that modern man had lost in the process of civilisation. And the voyagers willingly obliged. -- KARL H. RENSCH[1]

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, there have been a series of debates in the field of linguistics concerning the Amazonian language Pirahã. For the most part, those debates have revolved around a claim by the linguist Daniel Everett, that Pirahã lacks a formal property called “recursion” and that this poses problems for a research program advanced by Noam Chomsky. Discussion surrounding that single issue made the rounds in general academia, surfacing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, and then in the mainstream media, notably in a 2009 article in The New Yorker and a book (The Kingdom of Speech) by Tom Wolfe. From there, the debate metastasized into the broader popular culture.

I will say a bit about the recursion debate in what follows, but in this essay, I want to put greater focus on a more important claim that Everett makes about Pirahã in his article “Cultural Constraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã” (hereafter CCG). In that article, Everett argues that the (alleged) simplicity of the Pirahã language and other aspects of Pirahã life flow from the in-the-moment, immediate-experience nature of the Pirahã culture. As he puts it in CCG, “Grammar and other ways of living are restricted to concrete, immediate experience”.

In the case of Pirahã grammar, according to Everett, this restriction works as follows:

Pirahã culture avoids talking about knowledge that ranges beyond personal, usually immediate experience or is transmitted via such experience. All of the properties of Pirahã grammar that I have listed will be shown to follow from this. Abstract entities are not bound by immediate personal experience, and therefore Pirahã people do not discuss them.

We can call this the Immediacy of Experience Principle (IEP) and the facts that are alleged to flow from this principle are many. Again, from Everett:

Pirahã culture constrains communication to nonabstract subjects which fall within the immediate experience of interlocutors. This constraint explains a number of very surprising features of Pirahã grammar and culture: the absence of numbers of any kind or a concept of counting and of any terms for quantification, the absence of color terms, the absence of embedding, the simplest pronoun inventory known, the absence of "relative tenses," the simplest kinship system yet documented, the absence of creation myths and fiction, the absence of any individual or collective memory of more than two generations past, the absence of drawing or other art and one of the simplest material cultures documented, and the fact that the Pirahã are monolingual after more than 200 years of regular contact with Brazilians and the Tupi-Guarani-speaking Kawahiv.

We can understand the thesis in CCG as a kind of inverse Worfianism. Whereas, on the Whorf-Sapir hypothesis, language could determine culture and even reality (e.g. the Hopi language lacking a future tense determines an alleged impoverished notion of futurity in Hopi culture), in this case, the culture determines the nature of language and other cultural products. For example, the Pirahã culture’s lack of concern for the future and its prioritizing of immediate experience leads to a lack of future tense and recursion and other features of the Pirahã language.

As we will see, this inverse Whorfianism turns out to be an old idea – one that was operative with early European explorers and one that was formalized in Rousseau’s idea of the noble savage. In Rousseau’s account, the immediacy of the life of the noble savage led to simple languages and simple cultural products. The problem is that there is a long history of Western explorers seeing simplicity in other cultures when it simply wasn’t there. Rousseau provided an intellectual framework to justify the false exotification of indigenous peoples. The result was a project that provided pseudo-intellectual cover to a form of anthropology that falsely exoticized and primitivized indigenous peoples.

In what follows, we will see how, under Everett’s gaze, the Pirahã have also become exoticized, and we will see that the IEP has served as a kind of justificatory tool to make this exoticization seem scientifically legitimate – an intellectual framework serving a role previously taken by Rousseau’s theory of the noble savage. As we will also see, the IEP does not and cannot do the work that Everett wants it to. If the Pirahã were as exotic and as in the moment as he claims, the IEP would not explain why this was so. Hence the IEP is a kind of pseudo-scientific tool that fails to do what it is supposed to do – scientifically validate an attempt to exoticize the cultural products of an indigenous population.

In the end, we will also see that there is a paradox lying at the foundation of Everett’s project. Everett needs to claim that culture is an entity distinct from the products of culture – products like language, art, ritual, religion, and kinship – and that the culture “constrains” those products. But in doing so, he makes the notion of culture impossibly abstract – cut off from everything that is typically constitutive of culture (e.g., language, art, ritual, religion, kinship). The paradox in the case of the Pirahã is that they are supposed to eschew abstraction, even while their entire culture is (on Everett’s theory) driven by a decidedly abstract notion of culture, their language and other ways of life constrained by the pristinely abstract IEP.

Part 1: Exoticizing the Pirahã

When I read Tom Wolfes’s book The Kingdom of Speech, I felt that some of his interpretations of Daniel Everett’s work were pretty fantastic. According to Wolfe’s reading, the Pirahã have “not only the simplest language on earth, but also the simplest culture.”

They had no leaders let alone any form of government. They had no social classes. They had no religion. …They had no rituals or ceremonies at all. They had no music or dance whatsoever. They had no words for colors…”. You couldn’t call them Stone Age or Bronze Age or Iron Age or any of the Hard Ages because the Ages were all named after the tools prehistoric people made. They were pre-toolers.

They made no artifacts at all.

They spoke only in the present tense. They had virtually no conception of “the future” or “the past”, not even words for “tomorrow” and “yesterday”, just a word for “other day”, which could mean either one.

My initial thought had been that Wolfe had not read Everett’s work. How did he get to the idea that they had no tools? Everett, it seems, was talking about their tools all the time, if often about how they abused their tools. Everett said they had axes and machetes and bows and arrows and tools to make them and shotguns and motors for their canoes. They had pots and pans and ladders and who knows what else. And I have no idea where Wolfe got the idea that they had no music or dance. Everett goes to great lengths to describe their dances. He describes them dancing for 72 hours at a stretch.

But Wolfe is not wrong about other things that Everett claimed. Everett did say that they had no leaders or government. And he did say that they had no words for colors. He did say that they didn’t have much in the way of rituals, and he did seem to be saying that they lack a “concern” for the future and the past. He said things that might lead a reader like Wolfe to draw precisely the conclusions that he drew. And the other thing is, after these crazy interpretations started to appear in Wolfe and elsewhere, I am not aware of Everett making any written attempt to correct them.

1.1 No Future

Let’s begin with the issue of the future. Here is how the trailer for the movie, The Grammar of Happiness, introduces the topic.

Narrator: No past or future tense.

Everett: They let each activity be dictated by their needs of the moment. They live in the present.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMtdYiXvTcQ

Everett doesn’t exactly say that the Pirahã have no conception of the future, but in his book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes, he says that they have a “lack of concern for the future” and that this is a “cultural value” for them. One piece of evidence for this cultural value includes Everett’s observation that the Pirahã leave their tools in the fields rather than bringing them home at the end of a hard day’s work. I suppose you could say that this shows a lack of concern for the future, but on the other hand, the Pirahã might be thinking “I’m going to need to use this in the field tomorrow so why should I haul it back now?” I’m reminded of my junior high shop teacher excoriating us for leaving tools at our workspaces instead of putting them away. I don’t remember his exact words, but I am pretty sure he called us “irresponsible” or something like that. I’m quite sure he did not say “You kids are expressing a lack of concern for the future”. One might reflect on why such a statement is supposed to sound sensible when applied to Amazonian people and yet ridiculous when applied to American middle-schoolers.

You might be thinking that Everett must nevertheless have good reason for thinking that the Pirahã have a “lack of concern” about the future. But does he? Let’s stick with the tools (axes and machetes and whatnot). They did work and sometimes gave up goods to acquire those tools. Why sacrifice labor and goods to acquire bows and arrows and canoes and machetes if you don’t have plans to use them, and why use them to hunt or fish or tend to the manioc field if you don’t plan on doing something with the food that you acquire? Like, eat it. In the FUTURE. And the thing is, Everett reports that they acquire those tools at the beginning of the dry season, which suggests some level of seasonal planning.

One thing that caught my attention in his book Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes (I note, for the record, that the title itself seems to be offering future-oriented advice) is that just pages away from the discussion of the Pirahã’s lack of concern for the future, Everett describes an event in which the Priahã helped Everett repair his hut, and to do so they walked “several hours” into the jungle to harvest palm wood for the repairs. On the way back, when Everett’s 50-pound load of wood became too much for him, a Pirahã named Kóxói took his entire load and carried it back to the village for him. Here is how Everett described the event.

“You don’t know how to carry this,” was all he said. He was taking onto his shoulder perhaps fifty pounds extra. Fifty pounds is a heavy load when walking several miles down a narrow jungle path with low-hanging jungle vegetation. But he now carried at least 100 pounds. By working and sweating together, laughing at our own difficulties and errors, the Pirahã and I cemented friendships through these jungle trips.

I wasn’t there, but if I did all that work for someone – acquiring raw materials (palm wood) to fix their hut IN THE FUTURE so that they could have a nice dwelling IN THE FUTURE and I lugged 100 pounds of those materials back to the village for them and then the person I was helping said I had a “lack of concern for the future”, I might just tell them to fix their own hut next time and see how that goes.

I also want to point out that “cementing friendships” is a future-oriented activity. Maybe Kóxói was living in the moment and just lugging 100 pounds of palm wood for the pure joy of sweating together with Everett, but a more charitable interpretation might be that he too understood that he was cementing a friendship with someone who was, let’s be honest, a fairly important person in their village. Or maybe he did it just because he liked Everett a lot and wanted to see more of him in the future, or maybe he just wanted Everett to be happy in the future. But whatever the motivation, I don’t see why one would not say that Kóxói also wanted to “cement” his friendship with Everett, and that means he wanted to secure it for the future. When we primitivize a group of people and insist that they live 100% in the moment, we are apt to end up overlooking some obvious explanations for their behaviors – explanations that we would be happy to apply to ourselves.

Everett might be thinking that the Pirahã have a concern for the future, alright, but it isn’t really future future – it is just sort of future (you know, two hours of hiking in the jungle isn’t THAT far into the future). This raises a question: Just how far into the future do we need to look before we are actually seriously into the future, rather than just being in an insufficiently concerned relationship with the future? While it is true that the Pirahã are not concerned with their 401K retirement plans and pensions, might they not have other long-term concerns? To answer this question, I first need to pause and make a parenthetical observation.

Interlude about resistance to change.

In The New Yorker article on Everett and Pirahã, Everett is quoted as saying that “nobody has resisted change like [the Pirahã] in the history of the Amazon, and maybe of the world”. Everett certainly seems to like making grandiose claims, and this one, like many of his other claims, is positively Trumpian in its audacity. But is it even close to true? And if it was true, how would Everett even know? Over the last 500 years, lots of now-extinct Amazonian tribes fought to the death to resist colonialism. And even today there are plenty of Amazonian tribes that are bravely resisting illegal loggers, illegal miners, farmers and drug cartels, including the Guajajara (Tenetehara), the Munduruku, Matsés (Mayoruna), the Huni Kuin (Kaxinawá), the Asháninka, the Kayapo, and I suppose we could add the Yanomami. And we haven’t even started on the seventy to ninety uncontacted groups that are supposed to live in the Amazon basin and which Everett has never even seen.

Nevertheless, Everett believes he has sufficient grounds to say that NONE of them in the history of the Amazon and perhaps the whole world have been as resistant to change as the Pirahã. Setting aside the Amazon basin, we might also ask whether the Basques and the Irish and the Mennonites and the Hassidic Jews and the Sami and the Maori and the Kurds and the Sentinelese and the San People might have something to say about this. The Pirahã DID let a missionary stay with them (that would be Dan Everett) and that doesn’t seem like a lot of resistance to change, given that other Amazonian missionaries have been speared to death before they even left the river beach. And the Pirahã do use motorized canoes, which the Mennonites wouldn’t allow. But let’s ignore the Tumpian exaggeration and get back to the real issue. Let’s say the Pirahã are super resistant to change. Or at least somewhat resistant to change. What can we learn from this?

End of Interlude about resistance to change.

Believing that the Pirahã are super resistant to change, Everett’s first thought seems to have been that in their resistance, they are fighting to preserve the world for just this moment. That may be true, but notice that in their resistance, the Pirahã are also (intentionally or not) preserving their world for their children and future generations as well, and it is not absurd to think that this shows a very strong concern for the future – a future with sustainable agriculture, minimal environmental imprint, and without the toxic aspects of modernity. Is it crazy to think that the Pirahã might care about such things? And if they do care about such things, aren’t they the ones with a serious approach to the future? To sharpen this point, let’s imagine a Pirahã anthropologist sent to study United States culture. I imagine the first report coming back like this:

The United Statesians don’t appear to have a concept of the future at all. Their language certainly doesn’t have future tenses – they use modals, like “will”, suggesting a form of desire. And never has a tribe lived more in the moment. They destroy their environment and leave pollution everywhere. Everything is disposable. Nothing is sustainable. I was initially inclined to say that they have a lack of concern for the future, but on reflection, they have a toxic attitude towards the future. One might say that insofar as they have some concept of the future, they seem to hate it.

Issues with the future aside, perhaps the point Everett wants to make here is about the “living in the moment” vibe of the Pirahã, which could be true, but there is also the possibility that we children of the industrialized world have this fantasy about a better world that we project onto peoples about which we know so little. Rousseu’s era celebrated “the noble savage”, which was a European fantasy projected onto indigenous peoples. And this was how they thought about indigenous peoples at least until they had a dispute with their noble savages – at which point the noble savages became “brutal savages” in the eyes of the European invaders.

Noble savage or brutal savage, those were your options. It is almost as if Western explorers had two lenses through which they could see indigenous peoples. And it might be observed that to this day some anthropologists see indigenous peoples through one or the other of these two lenses. One is the lens that Napoleon Chignon used to view the Yanomami – we can call it the Hobbesian lens – which drew our focus to the brutal savage. Through the Hobbsian lens, we see indigenous people as living in a constant state of war and brutality. The other was the lens used by Everett – the Rousseauian lens – a lens which allowed him to focus on the Pirahã as simple, living in the moment, noble savages. And this is the lens that we are going to examine now.[2] Here is how Rousseau described the happiness of the noble savage in 1754, in his essay “On the Origin of the Inequality of Mankind”.

So long as men remained content with their rustic huts, so long as they were satisfied with clothes made of the skins of animals and sewn together with thorns and fish-bones, adorned themselves only with feathers and shells, and continued to paint their bodies different colours, to improve and beautify their bows and arrows and to make with sharp-edged stones fishing boats or clumsy musical instruments; in a word, so long as they undertook only what a single person could accomplish, and confined themselves to such arts as did not require the joint labour of several hands, they lived free, healthy, honest and happy lives, so long as their nature allowed, and as they continued to enjoy the pleasures of mutual and independent intercourse.

As we will see, this vision is quite sober compared to Everett’s description of the Pirahã.

1.2 Happy Happy Joy Joy

The thing that grips the imagination of people from Rousseau to the present day is the idea that because indigenous peoples – these noble savages – are so in the moment and so unconcerned with things and bosses, they must be the happiest people in the world. If you google “happiest tribe” the Pirahã will likely come up at the top of your search. And, as we noted, there is a documentary about Everett and the Pirahã called The Grammar of Happiness. Here is a remark from Everett in an interview about the documentary.

And what’s the evidence for their happiness? On the one hand every visitor that I take down to the Pirahã comments that they’ve never seen people smile and laugh so much. That’s one superficial evidence of happiness. But you also don’t find Pirahã sitting around depressed and crying. You don’t find chronic fatigue syndrome. You don’t find suicide. The concept of suicide is foreign to them. I’ve never seen evidence for any of the mental disorders that we associate with depression, sadness and lack of happiness among the Pirahã. They just work, they come home, and they talk. They’re happy. They sing at night. And they get up and do it again. It’s just an amazing degree of satisfaction without the need for consciousness-altering drugs or states.

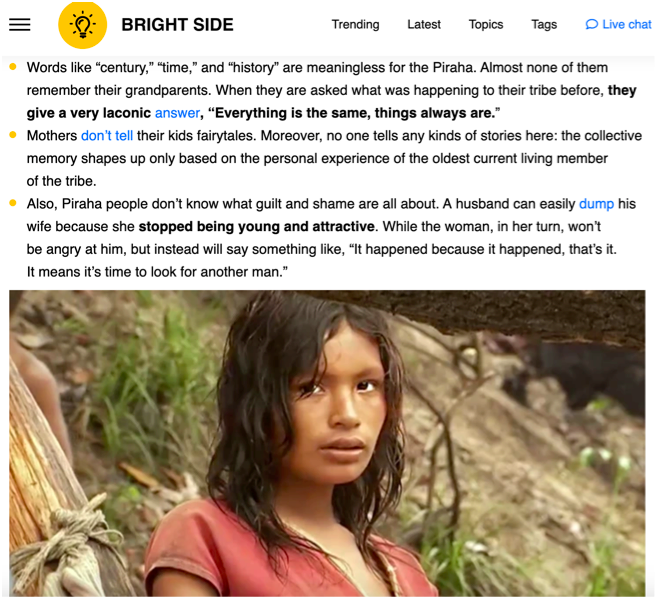

The Internet, like 18th Century Europeans, absolutely positively cannot get enough of this idea, as it is supremely memeable and at the same time speaks to the deep dark secret desire of most of the Internet, which is a life that is ultra chill. I present an example from the website Bright Side.

Screen capture from Bright Side website. https://brightside.me/articles/why-the-piraha-people-live-in-the-moment-and-are-considered-the-happiest-in-the-world-799555/

Screen capture from Bright Side website. https://brightside.me/articles/why-the-piraha-people-live-in-the-moment-and-are-considered-the-happiest-in-the-world-799555/

What bliss to be able to dump a wife, who, for some unknown reason “stopped being young” and to do it without her being angry. And in case you are wondering, all this actually is in Everett’s writing, and the bloggers and podcasters are absolutely mainlining this stuff. And Everett has more stories to tell us!

In the dry season when the river goes down and the beaches come out and the fish are easy to catch, they get together on the beaches in large groups. And you’ll find beaches with over 100 Pirahã for a couple of months during the dry season. And in that case, they’re singing and dancing every night. They could go on dancing for forty-eight hours, sometimes even for seventy-two hours. But that doesn’t mean that everyone’s awake for that entire period of time. It just means that you dance and dance and dance, and then when you get tired, you might step out and take a nap, and then get back up and start dancing again. But the noise and the happiness and all this stuff going on with it continues on. And if you’re like me, and not able to do that all the time, and trying to sleep, it gets frustrating! They’re just happy the whole time!

The problem is that there is extensive research on happiness in the psychological literature, and as a general rule, it does not involve chaperoning dances and reporting back on how much fun the kids were having. First, there is typically an operational definition of happiness, and people are actually surveyed, and not merely eyeballed. And that is because just eyeballing things isn’t all that reliable. And while you can define happiness however you want when you decide to study it (often definitions of happiness incorporate more than just in-the-moment good times, but also notions like contentment with satisfying life goals) you do need to conduct serious psychological surveys. And yes, Everett was there on the ground “living with them”, and I was there on the ground in my high school class of 400 students, but it would never occur to me to think I knew about the happiness of more than a dozen of them.

It should be pointed out that this characterization of the Pirahã also bears a striking resemblance to the reports from European explorers, who seemed to find similarly happy noble savages every time they went ashore. Consider Captain James Cook, upon discovering the aboriginal peoples of Australia (then called New Holland)

From what I have said of the Natives of New-Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholy unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniencies so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb'd by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life; they covet not Magnificent Houses, Houshold-stuff &Ca.

I believe that this is the passage that James Cook’s most famous biographer, J.C. Beaglehole, later dismissed as, “preposterous sublimity, this nonsense on stilts”.

Of course part of what sells this idea that the Pirahã must be the happiest people ever is not just the dancing and the guilt-free wife dumping, but also the idea that they have no bosses, and who doesn’t love that idea? But this requires some reflection too.

1.3 Freedom from bosses!

It needs to be asked whether Everett is accurately describing the Pirahã when he says they have no bosses. Just for starters, the Pirahã do have an official leader, at least in the eyes of the government and the Brazilian organization charged with protecting indigenous peoples (FUNAI) – his name is José Augusto Pirahã. Everett doesn’t recognize José Augusto as their leader, which is something else we will discuss later. But for now, I just want to point out that Everett is mining the great fantasy of Westerners, dating to the age of European exploration. What joy to be free of all those bosses!

Everett wasn’t the first to unsee the bosses of the indigenous Brazilians. Westerners have been doing this since the first day they set shore. For example, consider Amerigo Vespucci, after whom the entire western hemisphere is now named. Here is what he said in 1502 when he first encountered the coastal indiginous people of what is now Brazil.[3]

“They hold neither law nor faith none. They live according to nature. They know no immortality of soul. They hold no property of their own among themselves, for everything is common. They hold no terms of kingdoms or provinces; they have no kings, nor do they obey anyone: each is lord of himself. They do not administer justice, which is not necessary to them, because avarice does not reign in them”.

There was no shortage of early European explorers with the Everettian gaze. And of course, there has been no shortage of European scholars willing to synthesize these observations, the most famous of course being Rousseau. One of the key planks in the noble savage mythology was always that the indigenous peoples didn’t have bothersome rulers.

Society consisted at first merely of a few general conventions, which every member bound himself to observe. …. For to say that chiefs were chosen before the confederacy was formed, and that the administrators of the laws were there before the laws themselves, is too absurd a supposition to consider seriously.

Everett more or less follows in this Rousseuian vision, eager to claim that indigenous peoples in general do not have bosses:

A widespread belief is that most American Indians have chiefs or other kinds of indigenous authority figures. This is incorrect. Many American Indian societies are by tradition egalitarian. The day-to-day lives of people in such societies, many more than is usually realized, are free of the influence of any leaders. There are various reasons for the misinformed notion that most indigenous people of the Americas naturally have monarchical structures…. Western societies prefer that American Indians have leaders.

Does Everett believe that Sitting Bull and Geronimo and Crazy Horse and Chief Josef and Pontiac and Cochise and Red Cloud were just stooges installed by Westerners so that they could have someone to bargain with? As I noted earlier, the Pirahã do have an official leader, at least in the eyes of FUNAI and the police – the aforementioned José Augusto Pirahã. It may be that Everett doesn’t recognize him as a leader, but that isn’t Everett’s call to make. And it does drive home the point that Everett has this uncanny ability to not see things that are right there in front of him, whether they be indigenous leaders or a concern for the future or, (as we will discuss) recursive patterns in an indigenous language.

It needs to be observed that there are all kinds of bosses, and sometimes there are bosses that aren’t political leaders. For example, if you work for someone for goods or other forms of compensation, doesn’t that make them your boss? The thing is that bosses don’t always wear badges with their photo on them and they can’t always produce organizational charts to prove they are your boss and sometimes the true boss doesn’t even appear until there is a time of crisis. Sitting Bull might have seemed like just another tribe member until he had to deal with an existential threat to his people.

There is a lot more to be said about Pirahã bosses, and we are coming back to bosses in a little bit. But first, we need to step back and take in Everett’s big picture project, the aforementioned Immediacy of Experience Principle (or IEP), because that provides the scientific cover for this project of exotification.

Part 2: The Immediacy of Experience Principle Examined

According to Everett, the IEP is supposed to explain quite a lot, especially concerning language. As we noted earlier, all of the following cultural phenomena were supposed to be explained by the IEP.

- the absence of color terms,

- the absence of drawing or other art. They do not draw, except for extremely crude stick figures representing the spirit world that they (claim to) have directly experienced),

- the absence of creation myths and fiction,

- the simplest pronoun inventory known,

- the simplest kinship system yet documented,

- absence of numbers of any kind or a concept of counting,

- the fact that the Pirahã are monolingual after more than 200 years of regular contact with Brazilians and the Tupi-Guarani-speaking Kawahiv,

- the absence of embedding, (putting one phrase inside another of the same type or lower level, e.g., noun phrases in noun phrases, sentences in sentences, etc.),

- the absence of "relative tenses".

There are two questions that now need to be addressed. One question is whether these claims are true, but a second question is whether the IEP would predict these phenomena IF they were true. I want to focus on this latter issue first. As we will see, the IEP, examined closely, predicts none of these things to be true. If the IEP does not and can not explain the phenomena that Everett says it does, then what is the point of the IEP? My view is that it is only there as a kind of intellectual window dressing for his implausible empirical claims, as though theoretical support would make the claims seem more sensible. But the claims are not sensible, nor do they flow from the IEP.

For example, how would the IEP explain why there are no color terms in Pirahã, granting for the moment that there are no color terms? The problem is that if anything is immediately experienced it would be colors. Everett admits that the Pirahã talk about colors, and they perceive colors. So, what is Everett talking about? If experienced things can make their way into Pirahã grammar and they experience colors, how exactly is he supposed to have explained the alleged lack of color terms?

Being charitable here, I imagine that Everett is saying that color words (nouns) refer to abstractions that are associated with colors (e.g. they refer to redness, greenness, etc.) – abstractions which I gather are residing somewhere in Plato’s heaven. Because these Platonic forms for colors would be what color words supposedly refer to, Pirahã can’t have color words (because of the IEP). But of course, if you are going to be a Platonist about colors you can be a Platonist about anything – fish, trees, rivers, etc, and you could just as easily say that those Platonic forms are what the nouns “fish”, “tree” and “river” refer to (fishness, treeness, riverhood). Eventually, you can’t allow nouns for anything. But why start down this path at all? And why think that the experience of green is more abstract than the experience of a tree? Why not say that words like “tree” and “river” and “fish” are predicted to be unavailable because they are more abstract than basic experiential properties like colors?

Similarly, what does the IEP have to do with the ability to draw anything? Artists have been drawing things that they have experienced since the dawn of humanity. Artists don’t have to draw Platonic abstractions. Some artists draw what they see and experience. So how is the IEP supposed to explain the lack of representational drawings? Everett notes that they do use stick figures to draw spirit animals, which apparently must be less abstract than real animals, which are not drawn. I don’t want to get into a discussion of whether real animals or spirit animals are more abstract; my only point here is that both are EXPERIENCED. So how does the IEP explain the lack of drawing and other art (assuming there is a paucity of such things)?

While we are on this subject, what is the force of characterizing the drawings that are produced as being “extremely crude”? What is the definition of “crude” here and in what sense is the crudeness of the drawings explained by the IEP? Is the idea that their immediate experience of things is crude and therefore their representations must be crude (by the IEP)? What in the IEP would predict that the drawings are any less rich than the experiences themselves?

Everett characterizes the Pirahã as being irreligious, apart from the spirit animals that are quite present in their lives. Apparently, he has in mind the thought that traditional religions like Christianity don’t have a chance with the Pirahã, given that they violate the IEP. However, most evangelicals that I know talk about their personal experience with Jesus, and to be honest, Biblical stories are not the driving force in Evangelical proselatizing. Religious experience is. Indeed, it is a big part of most if not all religions that I am familiar with.

This leads us to the topic of rituals, Religious rituals can be ecstatic or sublime or comforting or frightening, but whatever they are, they are EXPERIENCES. So how is the IEP supposed to explain an alleged paucity of religious rituals among the Pirahã?

Creation myths might be ruled out by the IEP, but fiction? At least in the type of fiction I am familiar with, the idea is not merely to report events in some fictional world, but to be a mode of delivering experiences – experiences that can often be described as quite vivid. For that matter, I have long suspected that creation myths are more about delivering experiences than reporting on some historical facts. So even in the latter case, it would take a serious argument to show that the IEP ruled out creation myths.

Regarding pronouns, are there not people and things in the perceptual field to refer to? Are these things mere abstractions? Clearly not. Indeed, many philosophers regard pronouns as being “directly referential”, which means that these devices of grammar are direct links to things in the perceptual environment. Why on Earth would the IEP rule out such linguistic devices?

Everett assures us that the Pirahã have the “simplest kinship relations yet documented”, but if this is so, how would it be explained by the IEP? Understandably, the IEP might rule out things like great great grandparents, but most people have experiences of cousins and aunts and uncles and nieces and nephews and we do experience those relations in different ways. How does the IEP explain that there are no kinship terms for those relations?

You may be thinking that at least Everett has a point about mathematical objects, because they are nothing if not abstract objects, and yes that is a theory – you can be a Platonist about mathematical objects. But there is also a long history of thinkers, ranging from Husserl to my dissertation advisor, Charles Parsons, who noted that there is also such a thing as mathematical experience. (In Parson’s case, the mathematical experience mediates our access to abstracta!) For example, you don’t experience a yield sign as being merely a patch of yellow, you also experience it as being three-sided. I’m not saying everyone does, but many do. And maybe the Pirahã don’t experience mathematical properties of things in the world, but that does not mean that such properties cannot be part of immediate experience. And that means the IEP does not explain what is going on with the paucity of number terms.

It may be that “the Pirahã are monolingual after more than 200 years of regular contact with Brazilians and the Tupi-Guarani-speaking Kawahiv”, but then, after 200 years of regular contact, there must also be experience of these languages. So then how does the IEP rule out bilingualism?

I am going to save the topics of embedding and relative tenses until later, as they deserve a section of their own, given their apparent importance in the literature surrounding Everett and the Pirahã. For now, we have another question to consider. Are these claims of Pirahã simplicity even true?

Are these claims even true?

I cannot avoid thinking that the IEP was put in place to add a patina of legitimacy to a collection of empirical claims that, on the face of it, are just not credible. Are these claims just attempts to exoticize the Pirahã?

Let’s return to the issue of color terms. Earlier I observed that the immediacy of experience principle should not put a limit on the acquisition of color terms, so if there was a paucity of such terms the immediacy principle wouldn’t explain why. This having been said, is it the case that Pirahã has a paucity of color terms?

Everett says that instead of using a single word like ‘green’ the Pirahã use an expression that, translated literally, would yield ‘it is temporarily being immature’. Nevins, Pesetsky, and Rodrigues complain that this just is the Pirahã’s expression for ‘green’, and that to literally translate the expression in a way that reveals its etymology is another way to exoticize and primitivize the Pirahã. Their point is that that would be like making fun of us because of the etymology of our color terms. You know, like how “black” is from the Proto-Germanic “blakaz”, which meant “burned”. Or consider “orange”, which is just the name of a popular citrus fruit. Or for that matter, consider the etymology of our word “green”, which according to etymonline is “from PIE root *ghre- "grow" (see grass), through sense of ‘color of growing plants’”.

Everett seems to think that color words that are also the names of plants and other objects are no longer legitimate color terms (apparently our color terms “orange”, “lime”, and “silver” get grandfathered in) but we are still naming colors with this strategy. For example, Crayola currently includes the following colors of crayons: Lavender, Salmon, Mahogany, Cornflower, Sepia, Tumbleweed, Asparagus, Periwinckle, Plum, Copper, Shamrock, Denim, Eggplant, Beaver, Manatee, Fern, Canary, Almond, and (famously) Flesh.

Even when the Pirahã use complex expressions to designate colors, the theory of distributed morphology would just say that those are big words. And the Pirahã aren’t the only ones who use complex expressions for colors; we do it too. Crayola also includes the following color names for their crayons: Macaroni & Cheese, Granny Smith Apple, Wild Strawberry, Vivid Tangerine, Jazzberry Jam, Mango Tango, Mountain Meadow, etc.

While it is great fun to talk about color names, and I could probably do it all day long (we are only talking about crayons here – I haven’t even gotten to interior designer colors), there is this nagging question. What difference does it make if the Pirahã have lots of nouns for colors? Answer: absolutely none. The Pirahã still have ways of talking about colors. The human eye can distinguish 10 million different colors. We have chosen to name a tiny handful of them. If other people chose to name fewer of them or even none of them, so what?

I’m also skeptical about the claims made concerning its pronoun inventory. Everett notes that the Pirahã do have pronouns but he claims that those pronouns are borrowed from other languages. And that is interesting, to be sure, but the problem is that if something is borrowed into a language it is still, for all that, part of the language. Let’s be real, 80% of the words in English are borrowed from Latin (mostly via French). Even some of our pronouns are borrowed: “they”, “them”, and “their”, were all borrowed from Scandinavian languages. The thing is, we used those Scandinavian pronouns to replace pronouns that we already had (hie, heom, and heora). Even if you now have borrowed pronouns it doesn’t mean you didn’t have your “own” pronouns before.

Running through Everett’s analysis of the Pirahã language and culture seems to be this idea that he is only interested in some idealized pure form of the culture as he imagines it would be if it were free of non-Pirahã influences. In the political realm, this means he doesn’t see their official leaders because they are somehow not truly Pirahã. In their language he doesn’t want to recognize the elements of their language which he doesn’t consider kosher (pronouns, etc). However, it is not the business of an anthropologist or linguist to worry about the purity of a culture or a language. You study things as they are. And if, as they are, they have chiefs and pronouns, then that is how they are.

A good example of this involves his claim that there is a lack of ritual in Pirahã culture. Setting aside Everett’s account of 72 hour dances, which sound like rituals to me, I want to focus on his description of Pirahã burial practices. The pirahã are buried with grave goods, which already should be considered evidence of a ritual practice, but they also incorporate elements from other cultures. For example, Everett notes the following.

The corpse is placed in the hole. Then, after the possessions are added, green sticks are crisscrossed above the body, seccurely wedged into the hole. Over these are placed banana leaves or similar broad leaves. Then the grave is filled with dirt. Rarely, in imitation of Brazilian graves they have seen, they will place a cross, with carvings that imitate the writing they have observed on Brazilian crosses.

All of it sounds like ritual to me, noting that even when the rituals are imitative, they are still rituals.[4]

Nowhere is this methodological weakness more on display than when Everett talks about their mythology. He claims that they have no creation myths because such things are outside of Pirahã memory. But of course, anthropologists studying Pirahã have reported such myths.

Nevins et. al. (392) report that “a wealth of information about Pirahã mythology can be found in two extensive studies by Gonçalves (1993, 2001), an anthropologist who lived with the Pirahã for eighteen months over eight years (1986–1993), documenting and analyzing their cosmology (initially in the context of the conventions for naming children)”. Here is the beginning of one story. It’s about the recreation of the world by the demiurge Igagai after a cosmic cataclysm:

Everett claims that this is not a legitimate part of the Pirahã cosmology because it was borrowed. The sad part of that observation is that it apparently never occurred to him in his years as a missionary that the stories he was telling about Christianity were also borrowed. And if we really drilled down, many of the stories in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament were probably borrowed from bronze-age Mesopotamia.

My point is that languages and cultures are dynamic objects, and even isolates do borrow. When they borrow you can’t pretend that that doesn’t count. And in particular, given the methodology that Everett has proposed, you certainly can’t dismiss such borrowings, because his whole point is that the culture places constraints on what sorts of things are possible. If it is possible to borrow words and cosmologies and if the Pirahã can use and make sense of those borrowed words and cosmologies, well, sorry, but then they are possible. The Pirahã may not like the cosmologies, and they may not believe the cosmologies, but they clearly know them and understand them and can recount them in some detail.

I want to say something about the issue of lack of numerals in the Pirahã language. As I noted earlier, this is not unheard of. Walbiri and Yanomami and many other languages have a very small inventory of numerals (e.g. one, two, many). For some reason, people imagine that the expressions we have for mathematical objects are a natural part of human language, but this is far from obvious. Indeed, mathematical vocabularies seem to be something that you have to learn independently of your acquisition of language. The latter seems pretty much automatic, while learning number expressions is a grind. There are numerous psychological studies on this.[5]

Someday, aliens from another planet may show up and be surprised to learn that we have so few names for irrational numbers. I mean we have Pi, and Euler’s number. Square roots of primes, I guess. That’s all I’ve got folks, sorry. But the relative paucity of our mathematical vocabulary won’t mean that our language is more primitive. It will mean that we named fewer numbers than they did.[6]

Part 3: Language Through the Lens of the Immediacy of Experience Principle

It turns out that the IEP as a cultural constraint is an old idea, in particular as it relates to language, and it is most famously associated with Rousseau, who felt that the noble savage should have a simple language to go with his simple culture.

Often inspired by Rousseau, Western explorers have seen indigenous languages in precisely these terms since the day they began setting foot ashore. I began this paper with a quote from Karl H. Rensch, who is a linguist at the Australian National University who studies Polynesian languages. That quote came from a paper in which he examined the role of Rousseu’s ideology in coloring the vision that early explorers had of the Tahitian language when they first encountered it. For example, Rensch drew attention to Philibert de Commerson, a physician and botanist who accompanied Bougainville as a naturalist on his expedition. In a letter written in 1769 at Isle de France (Mauritius) and published in the Mercure de France in November of the same year, Commerson talks about Tahiti, the island he called 'Utopia' or 'Fortunate' and the language of its inhabitants:[7]

As Rensch notes, this observation has almost perfect fidelity to Rousseu’s ideas about language and culture, However, concerning the Tahitian language, Rousseu’s theory seemed to have overwritten the actual facts about the language. The reality is that the syntax of Tahitian is at least as complex as that of any familiar Western language.

Now we are being told that the simple nature of the Pirahã culture is supposed to be reflected in its syntax, and also the simplicity of its phonology. John Colapinto parroted this nonsense, evidently without reflection, in his New Yorker article about Everett and Pirahã:

When I read that passage I had to do a double take. We are told that Pirahã “has one of the simplest sound systems known” and then in THE VERY NEXT SENTENCE we are told that it has “a complex array of tones, stresses, and syllable lengths”. And the question has to be, why on God’s green Earth would this “complex array of tones, stresses, and syllable length” not make their sound system, well, COMPLEX? Just to frame this question up a little bit, let’s revisit our Pirahã anthropologist and this time let’s have them study the sound system of American English. I imagine the first report might read something like this:

Of course, the famous point of contention is about whether Pirahã has recursion, and we will get to that. But first, we need to reflect on a problem we Westerners have.

The problem is that we simply cannot get the idea of the noble savage out of our heads and we might “see” a noble savage in any sufficiently novel group we encounter. And when we receive reports of anthropologists off in some jungle having “seen” such noble savages, often with simple languages to pair with their simple cultures, the people back home simply cannot get enough of it. They want to believe it so badly that they will take it as a fact no matter how weak the evidence, or how strong the counter-evidence, and no matter how self-evidently preposterous the claims are. No concern for the future? No problem! Give us more! The people most resistant to change in the “history of the world?” Yes! Amazing! Keep feeding us that self-evident bullshit! No leaders? Awesome! One is reminded of the following passage from Geoffrey Pullum’s “Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax”:

Just like popular media could not get enough of the myth of the many Inuit words for snow, here we cannot get enough of the idea that these (and other) indigenous peoples are SIMPLE – their culture is simple, their language is simple, indeed their syntax is simple, their concept of the time is simple. Simple simple simple. We can’t get enough of it.

Part 4: Some housekeeping about Recursion

As we have seen, Everett made a lot of claims about Pirahã culture, but one claim in particular has garnered massive attention in academia, and also in the popular press. The basic idea is supposed to be that Pirahã lacks a formal property called “recursion”” and that this thus provides a counterexample to a theory that Noam Chomsky has proposed in theoretical linguistics. The Chronicle of Higher Education put it this way:

Tom Wolfe, in his book The Kingdom of Speech, simplified the idea thus.

The discussion surrounding this issue has mostly been at sea in a hurricane of confusion. I want to address this issue because it has, for some reason, become important. But before I can do that, we need to do some clarificatory housekeeping. By the time we finish this clarificatory exercise, the issue won’t seem that important. But once we see just how unimportant it is, we will revisit the topic and ask if the facts lie as Everett claims and if the IEP could explain why they lie in that way. The answers will be no and no.

To keep the discussion as tight as possible, I am going to only consider one version of Chomsky’s thesis – this version from a 2002 paper in Science by Marc Hauser, Chomsky, and Tecumseh Fitch (hereafter HCF). Everett, in his book Language: The Cultural Tool, incorrectly characterizes the HCF position as being that “all languages are based on recursion”.[8] This formulation is seemingly taken up without reflection by the Chronicle of Higher Education, by The New Yorker, by Tom Wolfe, and has now metastasized all over the Internet.

Everett’s formulation isn’t a good characterization of the thesis defended in the HCF paper, because nowhere in that paper, or any paper by Chomsky that am I aware of, is there a claim that “all languages are based on recursion”. Rather, the claim is that the CAPACITY for recursion is “a core component” of the faculty of language narrowly construed. Note that HCF nowhere say it is the only component, and they nowhere say that every language has recursion. Misunderstandings may persist if we don’t make a few additional distinctions.

First, we want to distinguish a recursive procedure from a recursive pattern or recursive representation. A recursive procedure is a procedure, or a function, that can be applied to its own output (computer scientists might say it is “a function that can call itself”). So, for example, consider a linguistic operation like merge. It can merge two syntactic objects, say “[likes]” and “[Pat]” yielding the merged structure “[likes [Pat]]” and we can reapply merge to this output and something new, like “Sam”, yielding a new structure thus: “[Sam [likes [Pat]]]”. At least as I understand the proposal in HCF, this recursive procedure is a “capacity” that the FLN has. At no point in HCF do they say that the recursive procedure must be invoked (or as a computer scientist would put it, the function need not be “called”). But there is a bigger issue.

When Everett and most other linguists talk about natural language being recursive, they are talking about a narrow class of recursive patterns that might emerge from this recursive procedure. So, for example, by merging a noun with another linguistic representation that contains a noun you get a noun within a noun – “[nut[tree]]”, or you might get a possessive within a possessive – “[Sam’s [mother’s [canoe]]]”. There is a second confusion in the debate beyond the capacity issue. Even if you run a recursive procedure, there is no guarantee that the resulting representation will have a recursive pattern like noun-noun, etc. Strictly speaking, you have a recursive structure the minute two objects are merged via a recursive procedure. As far as HCF are concerned, “[Sam [saw [Pat]]]” already is a recursive structure.

The big point is that nowhere in HCF do they say that human languages must evince noun-noun recursion, or possessive recursion, or any of the recursive patterns that are allegedly missing from Pirahã. They are clearly saying that humans have a cognitive faculty that gives them the capacity to generate recursive representations. HCF don’t say that the recursive function must be invoked, and they don’t say that if it is invoked it must generate recursive patterns of the sort that are allegedly missing from Pirahã.

What this means is that the fundamental question is whether the Pirahã people have the biological CAPACITY to learn a language with recursion. And no one, including Everett, disputes that they do. Here is the relevant passage in the New Yorker article, from an interview with Everett:

That should have been the end of the dispute right there.

The HCF thesis struck me as so obvious and so basic that in an earlier essay, I imagined the following encounter between Chomsky and the bearer of news about Pirahã.

Part 5: Does the Immediacy of Experience Principle Predict an Absence of Recursive Patterns?

The key idea behind Everett’s project, as noted earlier, is that culture determines the structure of language (among other aspects of life), and that simple in-the-moment cultures yield a simple syntax for natural languages. In this case, the idea is that the immediacy of the Pirahã culture – its alleged prioritizing of the present is what gives rise to a lack of recursive patterns in natural language. The thought is that if you can only report about what you immediately experience, that means that there would be no use for recursive patterns. I’ll let him explain (from his interview about The Grammar of Happiness).

And that follows from the principle of immediacy of experience that I’ve talked about. Because that immediate experience tells us that it has to have been experienced by the person speaking, or by someone who told the person speaking. And that is reflected in the grammar by these suffixes that tell us where the evidence comes from. And those suffixes, by their very nature, prohibit recursion.

There is much to talk about here. In the first place, a sentence like “John hit Bill” already would be a recursive structure on the account in HCF. So apparently, we are only supposed to pay attention to recursive patterns of a particular type – noun phrases within noun phrases, clauses within clauses, etc. Whether such patterns are important is one question that we won’t concern ourselves with here. Rather, we are going to focus on two alternative questions. First, would the IEP predict the absence of such patterns? Second, are such patterns missing from the Pirahã language? In this section, we are going to address the first question. Don’t worry, we will get to the second question in the next section.

We can begin with an important observation about our own language: recursive patterns ARE used to report on immediate experience. We use such patterns in the simple present tense all the time. Consider the following examples, which involve recursive patterns of the sort that are important to linguists, but which have nothing to do with “old information” in the sense discussed by Everett.

- That isn’t my husband’s canoe (possessive recursion)

- Are [S you trying to tell me that [S this isn’t his canoe?]] (clausal recursion)

- [S My wife is trying to explain to you that [S that isn’t my canoe]] (clausal recursion)

- I am talking about [NP the canoe under [NP the tree]] (noun phrase recursion)

- The [[N nut [[N tree]] (noun recursion)

- Yes, it is [PP under the tree [PP on the riverbank]] (prepositional phrase recursion)

Yes, I know that Everett is going to say that these aren’t expressed using recursive structures in Pirahã, and I will get to that in the next section, I promise. But right now, I am making a different point. The lack of recursion was SUPPOSED to extrude from the fact that the Pirahã are allegedly living in the moment and can only talk about what they see right here right now, but my point is that even if you could only talk about things that you see right here right now, there would be zillions of things you might say that could be expressed recursively. Recursively patterned sentences would be quite useful for people who live in the moment (if there are such people) and hence, according to Everett’s theory, recursively structured natural language syntax has no reason to be impossible for such in-the-moment people. You could be living 100% in the moment and be using recursive structures all the time.

Now I want to come back to the issue of Pirahã exoticism and ask whether it is true that the Pirahã culture lacks concern for things that happened in the past or the future or outside of their immediate perceptual experience. And what I am about to tell you is that even on Everett’s own descriptions of life amongst the Pirahã, if his description is correct, his claim cannot be taken seriously.

Early in “Don’t Sleep”, Everett tells the story of an event in which a riverboat trader sold cachaça to the Pirahã (causing them to get obscenely drunk) but also telling them that Everett was not paying them enough and wasn’t letting the trader pay them, suggesting that they kill Everett to put an end to these bad ideas about work compensation. This was taken at face value and considered perfectly reasonable grounds to kill Everett by at least one of the Pirahã, who, according to the story, did indeed threaten to kill Everett. Here is how Everett described the confrontation.

I heard Kóhoi’s voice from the bushes on the bank just behind me. “I am going to shoot you right now and kill you”.

I turned toward the voice, fully expecting to receive the full blast of his 20-gauge shotgun in my face or torso as I did. He came out of the bushes, unsteadily. But I could see with relief that he was not armed.

I asked, “Why do you want to kill me?”

“Because the Brazilian [trader] says that you do not pay us enough and he says that you told him he could not pay us if we worked for him”.

Let’s pause right there. First, there is a whole lot of recursion packed into the last part that last sentence. Kóhoi is explaining his motivation by saying that the Brazilian SAYS THAT Everett TOLD the trader THAT the Brazilian could not pay them IF they worked for him. This could be an example of recursion in a linguistics textbook.

[S The Brazilian says that [S Everett told him that [S IF they worked for him [S the Brazilian could not pay them]]]].

Clearly Everett will want to say that this is just his gloss of what Kóhoi said, and since that gloss was in English, he helped himself to layer upon layer of nested recursive structures to say what Kóhoi said. But THE WHOLE POINT of Everett’s IEP thesis is that because the Pirahã culture only recognizes immediate experience, they can’t have recursion. But here is Kóhoi, threatening to kill Everett, and justifying it not based on anything that he was seeing, or even that he SAW, but based on possibly false testimony from a Portuguese trader about a purely hypothetical situation (IF they worked for the river trader) based on something that Everett had allegedly SAID, IN THE PAST to the trader. And he packaged all that as a report of what the trader had said to him. If that kind of reasoning and discourse is part of Pirahã culture, why on Earth would the IEP exclude recursion?

The story doesn’t end there. That night, while the Pirahã men were drunk on cachaça, they went crazy, forcing Everett and his family to retreat into a storage room. Meanwhile, the women “had gone to the jungle to hide from their own husbands.”

Later in the day, after they had slept off most of their drunkenness, the Pirahã men came into our house to apologize, most of the women standing outside, shouting out suggestions for what the men should say to us. The women were also shouting directly to Everett and his wife. Don’t leave us. Our children need medicine. Stay with us. There are lots of fish to eat here and the Maici has beautiful water.

A remark on the Pirahã’s “lack of concern for the future” is in order here. I’m quite sure the women weren’t saying “Stay for the weekend”. If I had to hazard a guess, they wanted the Everetts to stay permanently, their children’s future health being at issue. Everett, being naturally concerned about his safety and the safety of his family, wanted to thwart any future troubles. He thus addressed a group of men.

You cannot threaten to kill me and scare my children. OK?

“OK!” they replied as a chorus. “We will not scare you or kill you”. In spite of the assurances that this would never happen again, I knew that I had to get to the bottom of what had transpired the night before.

If I had done something to offend them to the point that they would contemplate killing me, then I would have to figure out what the offense was and avoid committing it in the future.

We will follow Everett as he attempts to get to the bottom of the matter, but first, let’s think about this passage. Everett tells us that they live in the moment and are unconcerned about the future, but somehow, someway, they can give him “assurances that this would never happen again”. And “never again” sounds future-oriented to my ears. Bear in mind that the thing at stake was the future safety OF HIS FAMILY.

Everett, attempting to get to the bottom of the matter, ultimately brought some coffee and cookies to one Pirahã named Xahoábisi. The conversation went like this:

“Are you mad at me? I asked.

“No”, he replied, after he sipped his coffee. “The Priahãs are not angry with you”. (It is common for individual Pirahãs to phrase their opinions as coming from the group even if this is just their own opinion.)

“Well, the other night you seemed really angry”.

“I was angry. I am not angry now”.

“Why were you angry.?”

“You told the Brazilians not to sell us whiskey”.

Here we get to the issue of “no perfect tenses”. Let’s think about what is going on in that conversation. There is the past event of Xahoábisi being angry with Everett, and then there is the explanation of what caused him to be angry, which was something that Everett had reportedly done earlier than the event of Xahoábisi being angry, which was to tell the Brazilians to not sell them whiskey. In effect, the thought being conveyed by Xahoábisi is that he was angry because Everett had told the Brazilians to not sell them whiskey. This doesn’t mean that they have past-perfect tense morphology in their language, but they clearly have complex temporal ordering of events in their culture, so by Everett’s reasoning that should open the door to their language having a way to express such things. So how is the IEP constraining anything?

Meanwhile, before we leave this case, I want to come back to the topic of bosses, because it seems like Xahoábisi is a kind of boss. And more to the point It sounds a lot like Everett himself had become a kind of boss among the Pirahã by this point. First, it is clear from the conversation that Everett was paying the Pirahã to work for him – the bone of contention was whether he was paying them enough (the riverboat trader claimed he was not, and the trader also seemed to feel that Everett had a monopoly on their employment).

We don’t have to take the riverboat captain’s word about the boss part. Consider the following passage from the New Yorker article:

At sunrise, a group of some twenty Pirahã gathered outside Everett’s house. They were to be paid for their work as experimental subjects—with tobacco, cloth, farina, and machetes. “And, believe me”, Everett said, “that’s the only reason they’re here. They have no interest in what we’re doing.

The thing is, when people show up to do some work for you, and you are going to pay them, and they have no interest in what you are doing, well, I hate to break the news, but you are their boss! Even the cachaça-pushing river trader had this figured out.

“I want to know if I can take about eight men upriver with me to collect Brazil nuts”, he said.

“You don’t need to ask me. That is really none of my business. Ask the Pirahãs”.

He winked at me as though we both knew that I was just saying this for effect.

Everett even lived like a boss. In a village in which everyone else is living in what Everett described as “huts”, Everett built his own digs, which the New Yorker article described in the following way.

In the fall of 1999, Everett quit his job, and on the banks of the Maici River he and Keren built a two-room, eight-by-eight-metre, bug- and snake-proof house from fourteen tons of ironwood that he had shipped in by boat. Everett equipped the house with a gas stove, a generator-driven freezer, a water-filtration system, a TV, and a DVD player.

We can argue about whether that was an appropriate thing to do and we can ask what sort of impact such a structure and Everett’s jobs were having on this tiny community, but one thing we really can’t dismiss is this: Building that house was totally a boss-like thing to do.

Xahoábisi may not have been a de facto leader in the moment, and Everett may or may not have been a boss among the Pirahã, but a couple of things stand out. First, the Pirahã clearly had the concept of a boss, and Xahoábisi wanted to make it clear to Everett that he was not the boss when it came to Cachaça.

We are of course ignoring the “official” bosses, which Everett doesn’t seem to take seriously as bosses, in particular bosses like José Augusto Pirahã, who the Brazilian government and FUNAI and the police all recognized as the Pirahã leader. Why does Everett get to say that officially recognized leaders aren’t really leaders? Whatever the reason, it is a peculiar approach to anthropology.

Part 6: On the matter of recursive patterns in Pirahã

Let’s take stock of where we are on the matter of recursion. So far, we have made the following observations.

- The principal question is whether the Pirahã have the CAPACITY to call a specific recursive procedure (merge), that operates over linguistic structures.

- Having the capacity to call a recursive procedure doesn’t mean that you must call that procedure.

- The debate in linguistics is about whether Pirahã has a certain class of recursive patterns (patterns in which structures with similar grammatical categories are nested within each other).

- Even if the recursive procedure is called, it doesn’t entail that recursive patterns of the sort linguists care about will emerge.

- It is NOT the case that the IEP would explain the absence of such patterns.

This leads us to the question of whether such patterns do in fact exist in Pirahã. I believe that there are many languages that fail to evince such patterns and as far as I am concerned, it doesn’t matter whether Pirahã does or not. However, as much as I hate to go further down the recursion rabbit hole, there is an issue regarding Everett’s take on the matter which raises some interesting conceptual questions.

Just for the record, it appears that Pirahã has all the prized recursive patterns. Indeed, in Everett’s original papers on Pirahã, these recursive patterns are all over the place. For example, Everett (1986), points out that their word for ladder was originally a noun-noun compound built from the words for foot and handle. The word for bowstring was from a noun-noun compound built from the words for vine and bow.

More recent fieldwork provides additional examples. For example, Uli Sauerland (2015) reported recent fieldwork that shows that false belief reports are attested in Pirahã and that in such reports the contents of the beliefs are embedded under the expressions meaning “said that” and “believed that” (yielding clausal recursion). If the false claim wasn’t nested, you would end up asserting something false. Everett’s reports from the night of the cachaça were also unwitting reports of said-that constructions. The Pirahã were perfectly capable of explaining their past actions based on a report from the river trader without endorsing what the trader said. They didn’t endorse his claim that Everett told the trader not to pay them, they merely said that the trader said it. For that matter, they didn’t endorse the claim that they shouldn’t be paid (that clause was safely tucked inside two “says that” clauses – the river trader says that Everett said that if they worked for him, they shouldn’t be paid).

One form of recursive pattern that Pirahã appeared not to have according to Nevins et. al., was possessive recursion. However, in subsequent fieldwork, Raiane Oliveira Salles (2015) recorded constructions like ‘Kapoogo’s canoe’s motor is big’. The key point that this is a possessive embedded within a possessive.

Obviously, Everett changed his mind about recursion in Pirahã. He used to see it everywhere and now he sees it nowhere. The Everett camp claims that this change of position is a sign of his greatness as a linguist, because his continued careful study of Pirahã led him to modify his position. But the problem is that this change in perspective doesn’t involve a new discovery of some construction that he had not encountered in his earlier work. This involves him having to UNHEAR the recursive constructions that he had meticulously documented in 1986. So how did he unhear what he heard and reported in his 1986 paper?

We can answer this question by going back to the death threat from Kóhoi. Recall that we said that the English version of his remarks would be recursively structured thus.

[S The Brazilian says that [S Everett told him that [S IF they worked for him [S the Brazilian could not pay them]]]].

In Pirahã, according to Everett, the structure would be paratactic, which means it would be something more like this, without the nesting.

[S The Brazilian says that] [S Everett told him that] [S IF they worked for him] [S the Brazilian could not pay them].

But it is important to understand that, in his new, improved, less Chomskyan analysis, Everett doesn’t dispute that these constructions are interpreted AS IF THEY WERE recursively constructed. What does that mean? It means that they get assembled into nested structures, but not by the language faculty. They are assembled into nested structures later. Why? How?

As we noted above, Everett has a general view in which the syntax of Pirahã is simple (has no recursive patterns of the relevant sort) because there is no need for such expressions in Pirahã culture – they are ruled out by the IEP. Obviously, as we saw above, that doesn’t make sense, given all the future and past tensed deeply nested thoughts that Everett himself describes the Pirahã as having. But NOW it seems that these nested thoughts (which YOU thought were counterexamples) are being invoked to rescue the theory from the impoverished syntax that Everett is offering. The idea seems to be this: It is ok if the syntax is simple and non-recursive because the thoughts associated with those simple syntactic structures are complex and recursive.

So, what are we talking about here? The thesis was originally supposed to be that the syntax of Pirahã was simple because the culture was simple (by the IEP). But now we are being told that the syntax is simple, despite appearances, but that is ok because the thoughts associated with that simple syntax are complex. So, Pirahã culture can allow complex thoughts but can’t allow complex linguistic syntax. Why would that be? And how would the IEP figure in any such explanation? There is a bigger problem.

If the Pirahã culture allows complex, recursive thoughts but does not allow recursive patterns in its syntax, how would the Pirahã even know that they were violating a cultural constraint on their syntax? In this debate, we have Ph.D.’s in linguistics arguing about whether the syntax of Pirahã has recursion or not, and we are supposed to believe that Pirahã culture allows recursive thoughts but forbids them from expressing those thoughts in a syntax that has recursion.

Consider the recursive thought that is expressed by an utterance of “Kapoogo’s canoe’s motor is big”. Everyone agrees that the thought expressed by this is recursive. The debate is over whether the Pirahã version of that linguistic expression is recursive. Some linguists say it obviously does have nested recursive structure and Everett says it obviously doesn’t, and the last I heard about this, the debate turned on whether you could hear a pause in Salles’ recording of the data. The linguists I talked to say you can’t hear a pause. Everett says that you can. (No one seems to be asking why a pause would provide evidence one way or the other.)

My point is this: If linguists are sitting around arguing about whether this expression has a particular recursive pattern, how are the Pirahã supposed to know if they are (or anyone is) violating the alleged cultural constraint against recursive syntax when they use the expression? This would seem to require sending the Pirahã children to get PhDs in linguistics, resolve all the debates about the syntax of recursion, and then teach them that it went against their culture to use specific recursive patterns in the linguistic expression of their recursive thoughts!

But there is yet another problem with this strategy. Note that Everett COULD have said the exact same thing about every known language in the world. He could have said, that “this is the cat that ate the rat that ate the cheese” doesn’t have recursive structure; it is merely interpreted “as if” it had recursive structure. In reality, the syntax of English is just like this.

This is the cat. That ate the rat. That ate the cheese.

And then, somehow, we English speakers reassemble it and make sense of it AS IF it had nested clausal structure. If that strategy works for Pirahã then why wouldn’t work for English and German and Portuguese and Tahitian, etc.? The idea is that there are just a bunch of words juxtaposed, and we assemble them into meaningful recursive structures because we are so smart. Here is the relevant passage from the New Yorker article.

In his article, Everett argued that recursion is primarily a cognitive, not a linguistic, trait. … as Everett sometimes likes to put it: “The ability to put thoughts inside other thoughts is just the way humans are, because we’re smarter than other species”. Everett says that the Pirahã have this cognitive trait but that it is absent from their syntax because of cultural constraints.

Here we get to a basic confusion. The central project of cognitive science is figuring out how the mind/brain works, and it just does not help to say: Maybe we assemble all these words into a recursive structure because we are smart! The problem is that our smartness is the thing that we want to explain, and one way to approach that is to ask, what are the simple basic mathematical, physical, and biological principles that might explain how and why our minds work the way they do, and it is most assuredly NOT an explanation to say that it works that way because we are smart.

Recursive processes and their resulting patterns are found throughout nature. They range from the branches and root systems in trees to the fractal patterns we see in nautilus shells and in the spiral shapes of galaxies. When we observe these patterns in nature we want to explain them scientifically, and typically this involves looking for the low level mathematical and physical principles that drive these processes. We have yet to say that we think galaxies have spiral patterns because they are so cosmically smart. And we don’t say that trees develop the recursive patterns in their roots and branches because they too are so smart. Even if you believe trees have a form of intelligence and communication you do not make the mistake of saying that their smartness led them to develop recursively patterned root systems. That puts the cart before the horse. Trees, if they have intelligence and the ability to communicate, have it BECAUSE they have those root systems, and the growth of those recursive root patterns is driven by low-level biophysical processes that call themselves, not the smartness of the trees.

Of course we CAN use general intelligence, whatever that is, to build abstract systems that have recursive properties. We build logics that are recursive. These abstract systems were the result of impressive cognitive achievements by great thinkers and they followed in the wake of centuries of work in mathematics and logic. Learning about these systems is HARD. I know this because I’ve taught logic and I’ve taught formal semantics. Both subjects can bring good students to tears. And THIS kind of recursion is not what is going on when you and I and my students and the Pirahã build recursive structures in their representations of language and discourse. This natural form of recursion is automatic, it happens unreflectively, it is untaught, and it seems that everyone in the world (including the Pirahã) is good at it. We do it without missing a beat.

So no. We don’t say that nautilus shells and galaxies and trees and ferns and snowflakes and sunflowers decided it would be really smart to invent recursive patterns. So why would we say this about the unreflective recursion in human language and thought?

Part 7. A category mistake?