Philosophical Debunking (Part 1)

Interview by Richard Marshall

'The main thing I liked about my philosophy courses was that the professors were judgmental; they would evaluate claims as true or false, and dismantle arguments instead of just reporting the facts of the day. And, don’t ask me why, philosophy problems struck me as important problems, ones that you needed to get clear about before you packed it all in.'

'I concentrated on the many books promoting medical therapies that you can find in any bookstore at the mall, such as Bernie Siegel’s best seller some years back, Love, Medicine, and Miracles. An oncologist friend at the Mayo Clinic said all of his patients were carrying the book around. These books give you success stories: people who took the treatment and did well. This doesn’t amount to evidence because it is only part of the story and does not involve a comparison. We also need to hear about those who took the therapy and did not do well, those who did not take the therapy and did well, and finally those who did not take the therapy and did not do well. That is, we need to hear about four groups of people. You can arrange success stories in a two by two table: two rows, one for getting the treatment, one for not getting it; two columns for outcomes, good and not good. This gives you four cells in the table. You need entries in all four cells in the table before you can start talking evidence. No full story, all four cells, no evidence.'

'Homeopathic medicines are prepared by successively diluting the supposed active substance in a water and alcohol solution, and their claim is that the more dilute a medicine, the more potent, even if it the dilution passes the Avogardo point for molar solutions so that there is in all probability, or in fact, not even one molecule of the active substance left. According to homeopathy, nothing does something; according to chemistry, nothing does nothing. You can’t have your chemistry and homeopathy, too.'

'The holists’ tenets do not add up to a distinct conception of medicine--being just orthodox banalities, irrelevant truisms, useless exaggerations, or plain falsehoods-- and the holistic movement displays a reactionary impetus against the very ideas of scientific medicine and scientific reasoning itself.'

Douglas Stalker is a philosopher of science, epistemology, aesthetics, and logic. This is the first part of a two part interview in which he discusses Captain Ray of Light and Pseudo-Science, clear thinking, debunking alternative medicines, holistic medicine, and working on the American Cancer Society’s national committee.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

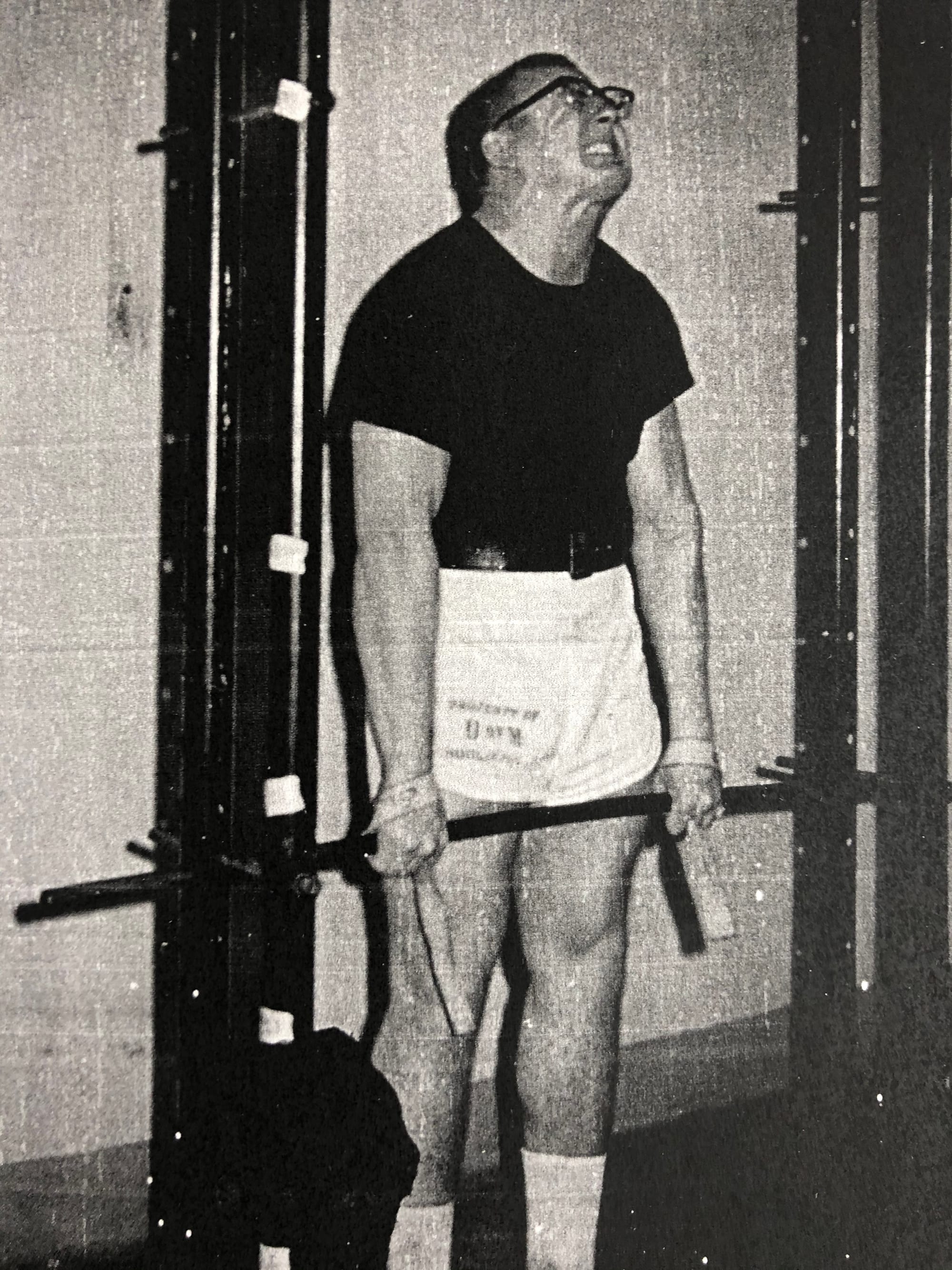

Douglas Stalker: It was fortuitous, that is, a fluke, and it involved a weightlifter, a war, a summer session, a poet, and a psychiatric social worker. I was gung ho about sports in high school, though a skinny, buck-toothed kid who wore glasses. In order to beef up for football, I started lifting weights and drinking some powdered supplement to add weight. It worked, since I went from 130 as a freshman in prep school to a senior who was over 225. And yes, I also discovered anabolic steroids along the way; one of our national-level lifters told me about them and also about amphetamines for those contest days. Back then, Olympic style weightlifting consisted of your best press, snatch, and clean and jerk. It was you against gravity, not some team, and slowly I changed my goals. I dropped football in my senior year, along with wrestling and shot put, to concentrate on lifting competitions. I still had offers from colleges for football, but ignored them. Who was Ben Schwartzwalder at Syracuse compared to people with multiple Olympic medals? I became a regional teen-age heavyweight champion and record holder, and went to periodically train where our best lifters did, the world and Olympic team members, some of whom were the best in the world in the mid-1960s. The American mecca of lifting was York, PA. One day in the York gym, I got to talking with Gary Cleveland, one of our world and Olympic team members; he was also a student at the University of Minnesota. Gary said that if I went to Minnesota as well, then we could train together. That was it; I chose my college on the basis of barbells.

When I was in Minneapolis for orientation, I didn’t have any idea what to take, so I asked Gary to help choose my courses. He, unknown to me, was a philosophy major, and he picked logic for my first quarter, introduction for my second quarter, and ethics for my spring quarter. I had never heard the word ‘philosophy’ before, and had come to Minnesota thinking about their five-year dental program; it seemed to answer all my questions about the meaning of life at the time. However, those afternoon labs in the chemistry courses went past sundown, and we were doing pointless make-work. Find the unknown? Hell, we put our heads together and one guy hit upon the unknown (thus making it into one of those known unknowns) and went to a chemistry supply store to buy enough to stuff our test tubes full of it. The TA was understanding, but noted that you can’t get more than a 100 percent yield, which we had.

The main thing I liked about my philosophy courses was that the professors were judgmental; they would evaluate claims as true or false, and dismantle arguments instead of just reporting the facts of the day. And, don’t ask me why, philosophy problems struck me as important problems, ones that you needed to get clear about before you packed it all in. Even so, I almost did not return to college after my freshman year, because flying home to New York for the summer, I sat next to a rather stocky man with a spiked beard and gravelly voice, Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon, one of the world champions in pro wrestling in 1966. We talked about his business and he sized me up: six feet, 252 pounds, an eighteen-year-old kid with a 21 inch neck who could do a full squat with a 500 pound barbell on his shoulders. He sat me down in O’Hare during our layovers and made me an offer: he wanted me to come back to Minneapolis right away, but not for school. I would live with Mad Dog and his brother, Butcher, in their trailer outside the city, and they would train me to become a pro wrestler. Many years later, one of my students became a pro wrestler, Raven, and he said it was quite an honor to have a person of Mad Dog’s stature offer to train you in the business, and gratis. I flew on to Rochester with Mad Dog’s contact information, but knew there was one big snag: the Viet Nam war. Vachon was a Canadian, so it never occurred to him that the war would pose a problem; it certainly did for me: I would be drafted unless I returned to school, not to mention my mother would faint at the thought that her prep school educated son was going to, well, grapple for money.

If it weren’t for the damn Viet Nam war, I would be a Vachon now. Or, as Raven maintained, dead from life on the road. Thus I returned to college that fall and went with philosophy as my major. Minnesota made you declare your major at the start of your sophomore year, and I had done well in my philosophy classes and all my other courses were a scattering of requirements and electives that happened to be open when I was eligible to enroll for the next quarter. What, really, was the alternative? During the summer after my sophomore year, I worked nights as a bouncer at Rochester’s largest rock and roll emporium, the Varsity Inn, and took a philosophy of religion course from Steven Cahn during the day at the University of Rochester. His course, and how well I did in it, confirmed my choice of philosophy as my major and put the thought in my mind that perhaps I could be a philosopher as well. My philosophy classes at Minnesota had been large, a hundred students or more, and to date I had only taken exams in philosophy. Professor Cahn’s class was small, about a dozen students, and he would sit on the edge of the desk and talk without notes. It was philosophy up close and personal. We had to write two term papers, each of which asked us to evaluate an argument, one by Richard Taylor and the other by John Dewey.

The papers were a first for me, and evaluating an argument was a brand new kind of assignment. I liked it and loved the class. I was, you might say, dizzy with awe. At Minnesota for my two remaining years, I took all the required courses and made sure, as well, to take Herbert Feigl’s course in the philosophy of science. I also found a new interest, poetry, as in writing poems. I won the Minnesota Creative Arts Festival prize for poetry, and then the Academy of American Poets prize, was published in the local outlets, and in my senior year I took, as an independent study, creative writing from Vern Rutsala, a visiting poet from Oregon. I think Vern ended up publishing about seven books and hundreds of poems in the quarterlies. He was nominated for the National Book Award for one volume, as I recall. Our last class was held at the Four Corners bar on the west bank of the campus. I wondered, by this time, if I might become a poet instead of a philosopher, and start by going to the Iowa creative writing program, which was the best in the country. After all, Vern had gone there for his MFA. However, Vern told me not to.

He said I should get a philosophy Ph.D. so I could earn a living, and there would be plenty of time for the poetry in my free time. This was before every school, large or small, added a poet to its English Department, and before I had any inkling about the job market in philosophy. I took his advice and started looking at graduate schools, sorting them by going to the open stacks of the library and seeing which schools were publishing in the journals. UNC Chapel Hill kept showing up, and so I applied there and was awarded an assistantship, and later an NDEA Title Four Fellowship. But that damn war was still going on, and I worried about keeping my deferment as a grad student. I had seen my older brother and his friends already go through machinations about how to beat the draft—lose a finger, take tons of antihistamine before the physical, act crazy, flee to Canada-- and I didn’t want to follow in their steps. I took a flyer, as it were. I went to the student health service and saw a psychiatric social worker there. Minnesota had a full service HMO, basically, for its students. They also liked to give the MMPI test to their students any chance they could. I think I took it three times, all 570 or so questions, so they had lots of psychological data on me. I asked the social worker to rummage around in my MMPI scores and see if anything was, well, out of whack because I thought I would make a better grad student than an infantryman, and asked if she would write a letter to my draft board.

The war was not popular on college campuses, and I had heard stories, as they say, about things being done. She calmly agreed to write the letter—no muss, no fuss, no argument at all-- and asked me what I wanted her to say. I told her that I never wanted to hear from these people again in my life. I had heard from them before. After my sophomore year, my local draft board had called me up despite that fact that Minnesota had dutifully informed them that I was a fulltime student and so warranted a 2-S student deferment. This became a protracted struggle, involving lawyers and finally the luck of the draw. The day before I was to report for duty, I went down to the draft office and talked to a different person--- the first one, whom I spoke to when all this started, had simply stonewalled me even though I could see the official documentation from Minnesota sitting right there in my file as she opened it on her desk. I don’t know what she had against me, but it was something. She denied what was right before her eyes. I was in school, I said; no you weren’t, she maintained. On my second visit, this new person simply opened up my file and said, oh, you have been in school, so this is a mistake. Indeed. Thus my history with the draft board was not a happy one. I never knew what she said in the letter, but I received a new draft card in the mail indicating that I was 4-F. I was considered unfit for service; I was golden and off to Chapel Hill for my professional training. A few years back, I wondered what that letter had said to get, without any tussle, the most coveted status at the time. When the draft board computerized, the old paper files had been expunged. We will never know how unfit I was.

[Image by Douglas Stalker: the cantaloupe crossing the table]

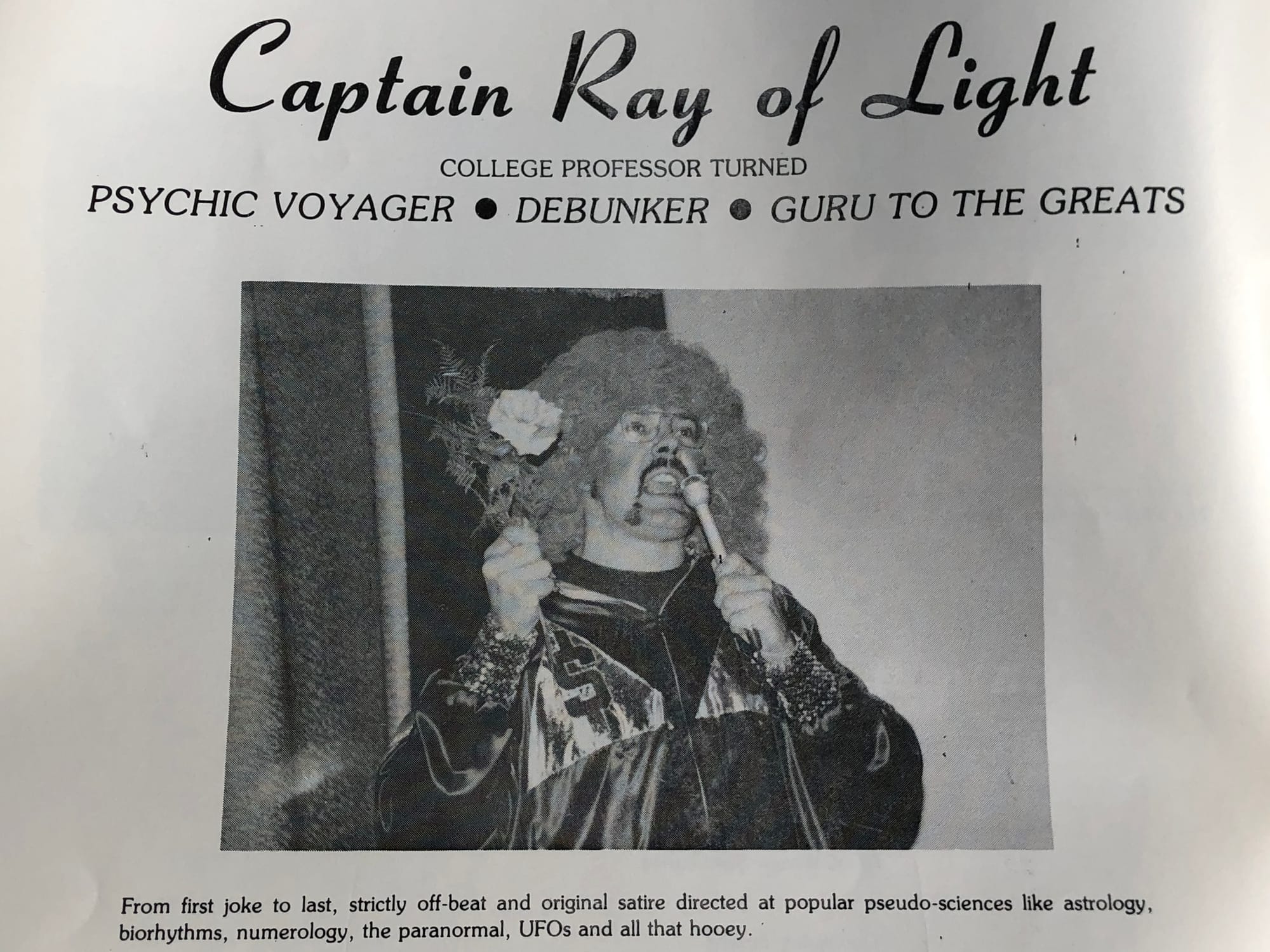

3:16: Your character Captain Ray of Light with his model pseudo-sciences-- Fascinating Rhythms, Alphabetology, and Peruvian Pick Up Sticks—is someone we need more than ever these days, what with post truth, no end of pseudo-sciences, and conspiracy theories running rife. You predicted that this gullibility and silliness were getting to be beyond just funny back in the seventies and eighties, and now it looks dangerous with a whole once-serious political party in the USA dominated by this sort of stuff. So first, can you tell us about why you invented the Captain, and what his six easy steps to success were designed to explain? You say you always hated pseudo-sciences, so were they never just light hearted fun for you?

DS: It all happened in 1979 when I was at Chicago Circle for the year. Clark Glymour and I wrote a satirical paper titled “Winning Through Pseudo-science”, which showed you how to make those big bucks, just like the pseudoscientists of our time did, by creating your very own pseudoscience. Ernie LePore, who was then at Notre Dame, invited me down to read both a popular paper to a large, general audience, and then a paper to the philosophy department the next day. I decided to read “Winning” to the general audience, and to perform it instead of reading it. This would go better in costume, so my T.A. at Circle, Big Steve Kovalec, and I had a blue sweatshirt made with the word ‘Pseudo-science’ on the front, with each letter ‘s’ as a dollar sign. We also had dollar signs on each upper arm of the shirt. Then we applied the glitter: two armbands on each sleeve, around the collar, and of course in stripes down the legs of the Army surplus pants I bought for the occasion. To top it off, we applied glitter around the rim of a blue baseball cap, adding a glitter dollar sign and also glittering the brim for good measure as well as a yard-long wooden doling with a dollar sign at the end, my official pseudo-science pointer. I prepared the appropriate transparencies for an overhead projector and chose a stage name. Captain Ray of Light won out over Ricky Rational. At Notre Dame, I slipped into a spare office along a hallway near the large library auditorium I was to speak in, and took my costume out of its garment bag. When I walked out in full costume, Ernie was stunned. He exclaimed, “Remember, I’m not tenured yet.” The Chairman was in the audience, as well as some colleagues. I told him everything was under control, and headed up the hallway, shedding glitter with each step.

His Chairman laughed along with the rest of the audience as I introduced them to the six fundamental principles of pseudo-science construction: a coincidence in the hand is worth two in the bush; a purpose to everything and everything to its purpose; the taller the story, the harder it falls; even physics isn’t all that precise; science is numbers and gauges; and finally, saying no to nitpickers by telling them they don’t understand, relying on the notion that one explanation is worth a thousand tests, quoting some big name, waxing philosophical, or counterattacking as the victim of narrow-minded expertise. I went on to build, before their very eyes, a true analog of Biorhythms, the even better Fascinating Rhythms with its three cycles the Mambo, the Rumba, and the Samba, which predicted Wilt Chamberlain’s highest scoring game and Janis Joplin’s death by overdose. Since once is not enough, I proceeded to build Alphabetology, which is light years better than numerology and astrology combined, since it relies on your Vowel Signs, Ascending Consonant, and Syllable House, which provided truly accurate readings for both Nixon and Hitler. In case you couldn’t build your own pseudoscience, I offered the audience a chance to buy a franchise in Peruvian Pick-Up Sticks. Our starter kit comes with a genuine Peruvian pick-up sticks board, an authentic Peruvian protractor, the three sticks (two called nebbishes and one called the Wong). A client casts the three sticks on the board and you measure the angles between the sticks and the Great Groove down the middle of the board, interpreting them according to the ancient principles found in the book My Thing, which is a faithful translation from the original Mayan. Within a few months of being back in Delaware and sending out a promo kit about my performance, I was doing shows at colleges all around the mid-Atlantic and the northeast, and had upgraded to a satin and sequin costume with a cape, a wig, script, professionally done slides, and wild gimmicks, psychic feats, and props. I even had a New York agent, New Line Presentations and was charging six hundred bucks on top of travel expenses.

Newspaper and magazine articles followed, even an AP wire service story sent nationwide, and Douglas Hofstader plugged the show in one of his Scientific American columns, also printed in his book Metamagical Themes. I was even selling Captain Ray of Light tee shirts at the shows; they had a sunbeam design, the Captain’s name, and the two words I ended every show with, the very same words that end Dianetics by L. Ron Hubbard: Good hunting! For those too cheap to buy a commemorative shirt, I tossed buttons—bearing those notable words—into the crowd as I exited. To start each show, I would run in throwing play money into the air to set the right mood, of course. Two radio stations asked me to play a psychic, one of them twice---the ABC affiliate out of St. Louis, for which I did cold readings for callers, and, as the host noted during a commercial, all the phone lines are lit up. Indeed, they would be with Captain Ray of Light on the line. I stopped doing the shows by 1990, and the costume now hangs on a mannequin here in my home in SC. My goal was to get on the Johnny Carson show, but that never happened. O tempore, O mores!

As for whether I ever took pseudo-sciences as just fun and games, along the lines of Clue or Scrabble: no, and for a simple reason. They make factual claims about the world and their proponents want you to believe those claims. Pseudoscientists are not in the same business as Milton Bradley, though of course from 8 to 80 can play.

3:16: Your comedy has a serious point, to develop critical thinking about the world. As I noted in the last question, conspiracy thinking, pseudoscience and similar stuff seems now quite dangerous. Making fun of the stuff is one approach, but how else should we tackle this problem as it seems that laughing at the stuff seems to end up making fun of people and their beliefs, and that tends to make them dig in rather than change their minds—after all, you didn’t tell you mother about this because she read the daily horoscope? Do you think we can learn to be clear thinkers, and is that what philosophers should spend more time doing?

DS: I started out covering pseudo-sciences in my Clear Thinking class at Delaware, and spun off a whole course on pseudoscience. It was a bust because it was too damn serious. When I gave straight-faced lectures, I had little success in changing hearts, let alone minds. Things changed when I took the comedy route and showed students how to make nutty analogs of well-known pseudo-sciences. They knew their analogs were nutty, and so they concluded, with lots of chuckles thrown in, that the well-known pseudo-sciences were as well. When I asked my students to make their own pseudo-sciences, they came alive. I still have some of their best work as memorabilia of the good times in class—Mailboxology, Padykula Rhythms from Jim Padykula, which has dials and gauges galore. One student turned in slides of Elvis, and a tape of excerpts from his songs, as proof positive of a new way to divine the events in anyone’s life. When I showed the slides on the big screen in one of those media-ready classrooms to about a hundred students, and added the tape of Elvis singing to my comments about the method of divination, the students roared so loud that professors in the adjoining rooms came to the door of my classroom to complain about the noise. I should have won a damn teaching award for that.

Anyway, I think you misunderstand what Clark and I were up to. We did not write for, nor did I perform for, the cranks among us. Our efforts were made in the hope that others, the vast, unwashed non-cranks, would see the cranks as fools or cons and their clients as dopes. If this ruffled the auras of some true believers along the way, well, collateral damage is a fact of life. I think a Radio Shack sound-meter would show that the majority of my audiences exited undamaged but enlightened through satire. You ask about whether people can learn to be clear thinkers, and whether philosophers should spend more of their time teaching clear thinking. Some people end up thinking pretty clearly, and since they didn’t come from the womb this way, I presume they learned it at some time or other. You probably mean something else by your question: viz., can you teach someone to think clearly? My answer is an unqualified one: you can, for some of the people, some of the time, to some extent. I don’t know who these people are and when you best can teach them or to what extent you succeed. No one has been serious enough to identify and measure these things. When I came up for tenure at Delaware, my dossier included a pre- and post-test, analyzed by a grad student in the ED school, suggesting that something was happening over the course of the semester; perhaps because of me, perhaps in spite of me. It had the look of a real experiment but it wasn’t; it was just a bluff for colleagues, chairs, and Deans. I never recall submitting my students to pre and post-tests again, though I have taught this course, and its relabeled successor, critical thinking, for almost thirty years. I started in 1977 teaching courses like this and didn’t stop until the end of fall semester 2005. Nowadays, every college, department, and course claims to teach students how to think better. They use the misnomer of the day, ‘critical thinking’. There is no such kind of thinking, while there is clear and confused thinking. The tin ear of academia! Lord knows how they fill in the specifics under the label of the today, critical thinking, since there is no fixed meaning to the phrase. Moreover, almost everyone simply assumes they are delivering what they advertise. It is taken on faith, which is just a sign that they are not serious about any of this. Happy talk is the order of the day down on the mall.

That is why I would not enjoin more philosophers to start teaching their little critical thinking courses sea to shining sea. It would just be going through the motions. For the most part, we give canned lectures, most of which is baby logic and a haphazard array of so-called fallacies, with some Mill’s methods thrown in for good measure. How much of this really applies to real world reasoning? We give canned little tests with minor, remote rewards and penalties. And no one checks to see if anything is happening other than more contact hours for the head count. The world would be a better place, I wager, if our students could parse and separate the claims in a few paragraphs of prose; detect blatant inconsistencies and equivocations; recognize where there are common sense alternatives to outlandish theories; recognize that an explanation is not evidence; recognize when real evidence is being presented and for which claims; and recognize and discount ad hominem appeals dressed up as arguments. This is a short list, but we can at least start here. And to get our students to do these six things, we need to make them practice, practice, practice, practice, and then hold out real rewards and penalties. In today’s world, we need video games in which players make their way through good and bad arguments and get a prize if they do. It didn’t take that in my day as an undergrad, but then I was odder than odd, and still am. As things stand, we largely don’t even try to teach clear thinking, or even put up much of a pretense. No one, it seems---from the administration on down to lowly adjunct faculty—is serious, and they are not because there are no academic incentives or levers to get the job done.

The result is that we have a mass of voters and rioters unable to think well and spot nonsense. They start with confused thinking in Sunday school and as they age that is just what they hear all around them from family, friends, radio, tv—an environment to encourage bad thinking before they even get to college. Perhaps it is too late when they get college. I would like to require them all to take a statistics course to graduate from college, something titled Statistics For People, and to have them know about the many real-world fallacies written about by Tversky and Kahneman, but you have to start somewhere, and start with some basics, and teach so as to change mental habits, and measure as you go to find out if anything good is happening. I threw in the towel long ago when I realized that the academic world around me was not serious about teaching better thinking (let alone teaching and grading most anything). It is easier just to invoke the magic phrase “critical thinking” and leave it at that. I would need to be the president of a university to right the ship and that certainly isn’t going to happen.

3:16: It’s an issue that you take up on numerous occasions when looking at so-called alternative medicine. I’ve even seen the bumper stickers! Do all these issues really circle that issue of getting people to ask: Where’s the evidence?

DS: Ah, bumper stickers. I used to give out “Clear Thinking” bumper stickers on the last day of class, but stopped when enrollments went into the hundreds per term. I made up “Where’s evidence?” bumper stickers to hand out at the end of a talk, by the same name, that I used to give to doctors, nurses, and patients. I eventually incorporated the points into my inductive logic course, which folded after a couple of semesters because no one would sign up for it. You are right, the basic idea here is the idea of evidence, and the basic question is where is it. If people would just learn to ask that question on a regular basis, as a habit, their clear thinking scores would zoom.

However, it is hard to get people to do just that. They seem to think it is unseemly and take offense at the idea that they have a, shall we say, homespun though errant notion of evidence. They take non-evidence for evidence all the time. In my talk, I concentrated on the many books promoting medical therapies that you can find in any bookstore at the mall, such as Bernie Siegel’s best seller some years back, Love, Medicine, and Miracles. An oncologist friend at the Mayo Clinic said all of his patients were carrying the book around. These books give you success stories: people who took the treatment and did well. This doesn’t amount to evidence because it is only part of the story and does not involve a comparison. We also need to hear about those who took the therapy and did not do well, those who did not take the therapy and did well, and finally those who did not take the therapy and did not do well. That is, we need to hear about four groups of people. You can arrange success stories in a two by two table: two rows, one for getting the treatment, one for not getting it; two columns for outcomes, good and not good.

This gives you four cells in the table. You need entries in all four cells in the table before you can start talking evidence. No full story, all four cells, no evidence. And also: no comparing, no evidence either. The comparison has to be a fair one. Differences between the groups could explain any differences between outcomes with an unconventional treatment and a conventional one. If the unconventional therapy patients are mainly young and in good shape, while the conventional therapy patients are mainly old and in in poor shape, then we don’t have a fair comparison. We do have an explanation for why the unconventional therapy patients are doing better, and the explanation has nothing to do with their therapy. It’s the covariates, not the treatments. In my talk, I would present these two rules about evidence---necessary conditions for having evidence—as well as some other rules, all of them based on the rows and columns in a two by two table.

You can screen out most all of the popular books on alternative medical treatments using these rules by making the appropriate entries in the table as you read along and then applying the rules. To make the point, I gave out my “Where’s the evidence?” bumper stickers to my audiences. When it comes to virtually all of the pseudo-sciences and crank medical treatments, their main problem is an evidence problem, as in lack of. It is almost definitive of the group. I discussed this more in an article in the Mt. Sinai Medical Journal , “Evidence and Alternative Medicine”, back in 1995. The paper was based on a talk I gave at a conference at Mt. Sinai Medical Center.

The director of the NIH Office of Alternative Medicine sat in the front row, and he didn’t look happy. My talk dealt with whether we should even try to obtain any evidence---direct, experimental evidence in people—for these therapies. Should we test these therapies (that is, hypotheses) or not? In the real world of medical science you must choose which hypotheses to pursue and which to ignore, and you can’t guarantee that our choices will always be the right ones. The best way to proceed with the choosing is by considering the prior probabilities of the hypotheses in question---the estimates of the probabilities that each hypothesis is true before it is actually tested in a clinical trial format. A prior probability is a summary of background information and beliefs that bear on the truth of a hypothesis, and there are some straightforward reasons—basic science reasons, source reasons, and methodologic reasons—for thinking that when we rank conventional and alternative competing hypotheses in terms of their prior probabilities, the alternative hypotheses will be at the bottom of the list. Moreover, there are straightforward problems with one type of background information that proponents of alternative therapies typically emphasize, information about positive cases.

Let me give some examples of these sorts of reasons. Many alternative therapy hypotheses agree with theories that do not have a good deal of scientific support, and this lowers their priors. Both immunoaugmentative therapy and the Simonton psychological therapy for cancer are based on the immune surveillance theory of cancer, and that theory, according to which the immune system recognizes and destroys cancer cells in humans, has little support behind it. Down goes their priors. Some alternative therapy hypotheses are logically Incompatible with a well-established pieced of basic science information, and this lowers their priors, sometimes so much so that the prior is virtually zero. Open any standard anatomy text and you will read that the eight skull bones of the human cranium are fused together by two years of age, and so at that point the eight bones cannot move unless, in effect, you break the cranium. Cranial osteopathy holds that these bones can move out of alignment and cause anything from dyslexia to dental problems, and the therapy for such problems consists in gentle manual manipulation to realign these bones. After age two, either the bones move or they don’t. Basic anatomy is certain that they don’t move. The prior for cranial osteopathy is thus next to nil, if not nil.

Homeopathy runs counter to Avogadro’s number, the number of molecules in one mole of any substance, which is a physical constant in chemistry. Homeopathic medicines are prepared by successively diluting the supposed active substance in a water and alcohol solution, and their claim is that the more dilute a medicine, the more potent, even if it the dilution passes the Avogardo point for molar solutions so that there is in all probability, or in fact, not even one molecule of the active substance left. According to homeopathy, nothing does something; according to chemistry, nothing does nothing. You can’t have your chemistry and homeopathy, too. The prior of a typical homeopathic therapy hypothesis is zero. A therapy hypothesis does not come out of thin air; it has a source. As they say, consider the source because this can influence a prior probability. In a little paperback titled Killing Cancer, Jason Winters claims that tribalene herbal capsules are an effective cancer treatment. He discovered it on his world travels and believes it cured his own brain tumor. Winters crossed the Canadian Rockies, hunted polar bears and kangaroos, appeared in a Western film, and been a stunt man. He is a colorful person, but what is the probability that tribalene is really an antineoplastic agent that a person like this discovered in his travels? Vanishingly small. Dr. Bernie Siegel is a less obvious case. He promotes a psychotherapeutic approach to cancer as an effective treatment. He spells this out in his bestseller, Love, Medicine, and Miracles.

When the book was new, a Mayo oncologist told me that all of his patients had a copy. Siegel was trained at good medical schools, and practiced pediatric and general surgery in New Haven, CT. He is no Jason Winters, but there is more background information to consider, his 225-page book. Dr. Siegel wrote popular books instead of articles for medical journals, and so we must judge the caliber of his thinking about the topic by judging his book. One way to do that is in terms of how many errors the book contains: there are errors on almost every page, and they are not sophisticated ones. For example, he commits the fallacies of post hoc, ergo propter hoc, of arguing from supporting data only; he misinterprets published studies, presents false analogies and false dilemmas, claims to know things no one can know, makes inconsistent claims, makes claims characteristic of pseudoscience, and more. I sent my friend at Mayo a complete list of the errors in the book so that he could show it to his patients, and then ask them: would you buy a used cancer therapy from this man? The pattern of error simply undercuts the information about his medical training, and so the prior for Siegel’s therapy hypothesis is exceedingly low. All of this can be put in terms of likelihood ratios showing which pieces of information are more informative or diagnostic than others, but I will spare you that. Now let me discuss some methodologic reasons for estimating prior probabilities. You can evaluate hypotheses in terms of how well they satisfy criteria such as simplicity, generality, modesty, refutability, and precision. This is just The Web of Belief applied.

Back in 1988, a clinical trial was run in the Netherlands to test out two paranormal hypotheses—laying on of hands and healing at a distance—for essential hypertension. If other things are equal, any normal competing hypertension hypothesis will be both simpler and more modest than these paranormal hypotheses, and so would have a higher prior. If one hypothesis assumes only one rather than two basic kinds of things and events, and also assumes the more usual and familiar kinds of things and events, then it is both simpler and more modest than any that assumes there are two kinds, and very unusual and unfamiliar kinds, out the in the world. You can only wonder why the Dutch investigators chose paranormal hypotheses to test for a medical problem that must attract no end of normal therapeutic hypotheses. The NIH has funded tests of prayer hypotheses, therapeutic touch hypotheses, and Qigong hypotheses; they typically have the same problems with simplicity and modesty by assuming we are in a world with both the usual physical things and events as well as unusual, nonphysical ones. Some people try to mitigate these problems by suggesting that if such hypotheses are found to be true, then we may also find that they involve nothing more than physical things and events.

This, however, does not change the status of a paranormal hypothesis; it introduces a competing, normal hypothesis which we need to estimate the prior for. At last we come to the stock in trade of alternative medicine: success stories, testmonials, or, as I put it, positive cases---a person had the therapy and had a positive outcome. A number of positive cases might seem like a good reason for raising the prior of an alternative therapy hypothesis. Not really. First, virtually, If not literally, every alternative therapy has positive cases, but not every such hypothesis is true. Even the alternative medicants agree about this. And it means that positive cases do not, by their very presence, distinguish the true from the false therapy hypotheses; positive cases alone do not change the priors of these hypotheses. No matter, the NIH unit devoted to alternative therapies wants to use positive cases to see which therapies are worth putting to a test, especially cancer therapies. They want alternative practitioners to submit their best positive cases for a review by a panel of experts, who will then judge if any show signs of tumors shrinking. However, they do not say a word about how they, or anyone else, should draw a conclusion from a collection of such cases—say from at least one partial or complete response in a collection of 20 cases.

A very good best-case review would be a collection of 20 cases, all judged to show positive responses to measurable disease. If these are convincing results, results that merit further investigation, the probability that you would see 20 such cases, given that the therapy hypothesis is not true, should be low. However, there are straightforward reasons for thinking it will high. In effect, how easy is it to get positive cases here? Pretty easy. All it takes is some perseverance. Suppose a practitioner treats 14 patients with solid tumors, and none has a positive response. Undeterred, he treats another 45 patients, and one has a positive response. He now has his first case for a best case review. He proceeds in the same manner with the next 59 patients, so he then has his second best-case. If things proceed in this manner eighteen more times, the practitioner has his 20 best cases from seeing a total of 1,180 patients in 20 different groups of 59 patients. You can view each of these groups as a Gehan two-stage phase II clinical trial of a new chemotherapy drug. The Gehan setup is a standard one for determining whether a drug shows anti-tumor activity that merits further investigation.

The first stage of a Gehan trial consists of 14 patients and you commonly do not proceed to the second stage unless you see at least one positive response; the second stage consists of 45 more patients. If a drug does not reach stage two, it is deemed worthless and discarded. Our alternative practitioner did not see even one positive response in his first 14 patients, and so should have concluded his therapy is worthless and discarded it. But he continues on, in effect, to stage two of a Gehan trial and sees a positive case, which he can set aside as his first of 20 best cases. His therapy receives, in effect, 20 Gehan trials of two stages, and yet his therapy does not warrant passing into stage two in any of these 20 trials. It should be discarded twenty times over, but it isn’t because an advocate is in charge rather than an investigator. Each of his best cases is a spurious response. The chances of this happening depend, for the most part, on how many cases a practitioner treats and how often spurious responses occur.

You can get an estimate of how often spurious responses occur by looking at trials that used discontinued anticancer agents. In a review of 26 discontinued agents, 56% of the agents had a positive response rate of at least 7% per 14 patients in two-stage trials. Our alternative practitioner had a response rate of 1.7% per 14 patients. I presume that more than 56% of the discontinued agents would have at least a 1.7% response rate per 14 patients treated, and that the probability of seeing spurious responses increases as you treat more patients. If an alternative practitioner treats 1,180 patients, I would estimate he stands a 65-70% chance of seeing 20 spurious responses even though his therapy is a dud. If he sees these responses and does not deem them spurious, he has the makings of an OTA best-case review that is not evidence of anything other than persistence.

3:16: Of course out of this came your book with Clark Glymour attacking holistic medicine. Can we look at that in a bit of detail because it helps us see how to work through and see the issues and understand how there are several dimensions to the issue. Can you sketch for us what you cover in this book in general and then, in particular, tell us about your contributions?

D.S. Actually, the talks and some of my articles on crank medicine came before our volume. Examining Holistic Medicine came out a long time ago, 1983, but it is still the best volume to date on crank medicine—and the only one written at the adult level on this topic.

The review in JAMA enjoined every responsible health professional to buy the book. I can report that they have not complied. We were also threatened with a lawsuit from the American Chiropractic Association, who found some copyrighted, patented gadget discussed in the chiropractic chapter. The publisher, ignoring that we held the copyright, negotiated a settlement that consisted of pasting over a paragraph with a revised version. It was changed by one word; the word ‘quack’ was changed to ‘unscientific’. That seems like changing ‘ass’ to ‘jerk’, so of little moment. The publisher didn’t want to defend the book because, as they told me, it hadn’t made them any money. The chiropractic association also wrote to Clark about me. I had given a talk up in the Lehigh Valley on holistic medicine and discussed the chiros. There must have been a rat in the audience who ran to the powers that be in the land of spinal adjusters. The letter to Clark said that if he were looking into holistic medicine, they could pair him with a much better person than the uninformed me. Nice people, aren’t they? But I digress. The volume has twenty selections divided into four sections.

The first section is on the background of holistic medicine and some of the controversy surrounding it. This section has our New England Journal of Medicine paper, “Engineers, Cranks, Physicians, Magicians”, as well as an essay on the doctrinal precursors of today’s holists, the alternative medical practitioners of the nineteenth century who promoted homeopathy, hydrotherapy, and hygiene therapy. This section also includes an essay on holistic nursing, a field in which the holists had made large inroads in nursing education, research, and practice. The second section is on holistic philosophy, and includes essays that analyze the holistic tenets about the role of one’s mind in disease and its cure, about how quantum theory supposedly shows contemporary medical therapy and research are in error, about how holism, as a view, is at odds with both reductionism and mechanism, and about how individuals are responsible for their health. The third section examines holistic methodology, and includes an essay showing how holists often try to support their practices in ways that are characteristic of pseudo-sciences, and an essay that documents the woeful methodological standards of the research published in the Journal of Holistic Medicine .

The fourth section covers many holistic practices: acupuncture, biofeedback, chiropractic, homeopathy, iridology, herbal medicine, high dose vitamins and imaging for cancer, holistic psychotherapies, and therapeutic touch. Of particular interest here is the chapter on chiropractic, written by the late Edward Crelin, a world expert on the functional anatomy of the spine. When Ed learned about the lawyers coming after his chapter and how changing one word was the result, he assured me that the chiropractors had subjected his chapter to a word by word reading in the effort to find something wrong, and this is the only thing they could come up with-- one word? The volume is still current after all these years: although the words may change in holistic circles, the song stays the same. The area displays a willful intransigence to sensible criticism and evidence-based development.

The idea for the volume occurred to us after we had published a paper in the NEJM, the one that now opens the book. There we show that the holists’ tenets do not add up to a distinct conception of medicine--being just orthodox banalities, irrelevant truisms, useless exaggerations, or plain falsehoods-- and the holistic movement displays a reactionary impetus against the very ideas of scientific medicine and scientific reasoning itself. Here is one banality from the holists: a physician must take into account the many circumstances contributing to a medical condition. Indeed, but that is not the makings of a distinctive conception of medicine. Or this: mental and physical states are interdependent—one causes the other. Who thought otherwise? You can find holists claiming that everything affects your state of health, which no doctor could incorporate into their practice of medicine for the simple reason that no one can pay attention to everything. Some holists pronounce that all states of health and disease are really psychosomatic, which is just a flat out falsehood---think of genetic disorders like Down’s syndrome or infectious diseases like cholera. There is, to boot, an odd view of how our bodies function that shows up time and again in holistic writings: viz., you can diagnose or treat the whole body by observing or treating one part of its anatomy. Iridologists and chiropractors are good examples of this—a view that is plainly at odds with what the sciences tell us.

Moreover, holistic practitioners do not feel obliged to prove their treatments cause good outcomes. It’s all because each person is unique, every part of your body depends on every other part, minds can’t be separated from bodies, and the mind acts otherwise than things act in the physical world. In short, it’s all magic. Holists thus go out of their way to denigrate rational assessments of their offerings. Scientific reasoning, they tell us, has been distorted by economic concerns and a conspiracy of disinterest from the conventional side. To be sure, some negative evaluations of a holistic practice may have been, but all? Holists tell us to keep our minds open and to fund investigations of their practices. You would need to keep your mind so open that your brain would fall out to take iridology or zone therapy, seriously, to cite just two practices. We know more than enough about functional anatomy to conclude that you can’t diagnose all manner of disorders by looking at geometric features of the iris, and that you can’t cure all manner of disorders by massaging a foot. And if you really want a test, it would be cheap. It has been run in the case of iridology as the chapter on this diagnostic practice reports in our volume. There are big rewards, monetary and otherwise, for scientific investigations showing us new and cost-effective therapies. Holists know this, but have been unable to come up with good scientific evidence for their practices.

What to conclude then? The practices do not work as advertised. Holists go beyond belittling scientific reasoning; they want to toss out science and reasoning altogether. How? They like to invoke Kuhn and they claim that holistic medicine is another paradigm in competition with conventional medicine, and so regular doctors can’t understand or evaluate it. They fail to see that holistic medicine is not a scientific tradition because it does not have paradigmatic work, an accepted set of problems and shared set of standards on what counts as a solution to these problems, or any of the critical exchange among its practitioners so typical of the sciences. Holistic medicine is no competing paradigm and the hodgepodge of holistic work is not a scientific revolution in the making. Some holists go on about relativism to undercut scientific reasoning, claiming that all evaluations of medical practices are relative to culture, with the upshot being that one culture’s physics may be another culture’s pseudo-science.

Of course different cultures (and subcultures) produce different beliefs about medical and other topics, but why in the world should we suspend our judgement about them and give equal credence to them all? And then there are the holists who maintain, for example, that traditional Chinese medicine and its standards are incommensurable with Western medicine, and both are equals when it comes to producing medical knowledge. It would be beyond tedious to go into why the two systems can be compared, and why a centimeter-gram-second system of measurement from physics, along with methods of good experimental design, are better than ideas about wood, earth, metal, fire and water and just catch-as-catch can trial and error. To do that, you would need to make use of knowledge and use reasoning that is not limited to a geographical area or a nationality. Our second paper in the book is about how the holists regularly misuse quantum theory and philosophy of science as they go on about consciousness, reductionism, and causality. It is odd to find medical people, albeit holists, writing about quantum mechanics in connection with their favored medical therapies; you won’t find anything like this in the standard medical journals such as JAMA, NEJM, and the Lancet.

The holists seem to think that quantum theory shows something general about methodology and the structure of our world, and these general points show that conventional medicine and its research is wrong, while that of holism is right. Supposedly quantum theory shows us that human consciousness creates reality, that big things cannot be reduced to little things, and that conventional medicine relies on an outdated and incorrect idea about causal relations. These holists simply do not understand the scientific process, and what they say about contemporary physical science and its implications is simply false if not absurd. They wallow, in effect, in quantum silliness. I will forgo a summary of quantum theory and things like the measurement problem and Bell’s theorem, going right to the silliness. The holists appeal to one controversial interpretation of quantum theory, Eugene Wigner’s, to bring consciousness into the picture here. On Wigner’s interpretation, human consciousness does have a role to play in determining quantum states. However, in that role it just determines which variables a quantum state happens to be an eignstate of—when a state determines a unique value for a variable, it is then said to be an eigenstate for that variable. On Wigner’s interpretation, your feelings and emotions are irrelevant to quantum phenomena.

Holists also appeal to the role of consciousness in quantum theory to support their claim that science is more subjective than objective in its workings: e.g., diagnosis is subjective, and scientific research is hardly objective. The unvarnished idea here is that what exists depends on what you want to exist or how you feel about it existing. Quantum theory has nothing at all to do with this. Particle physics has not become, in the wake of quantum theory, you have your particles, I’ll have mine. The hundreds of physicists who spend years on their projects, and millions and millions of dollars on them, have not dropped what the holists like to call, as if it were disparaging, the conventions of objective research. They are occupied in designing reliable apparatus, trying to reproduce results, and constantly checking and rechecking for errors. What do the holists think they would say about this imagined implication of quantum theory for their work? Or just scan the pages of the top physics journals to see if consciousness is a variable in today’s physics; quantum theory has not made physicists do psychology before they can do particle physics.

Holists also go on about reductionism, which they claim quantum theory has shown to be a serious mistake, and so fields like molecular biology are in error when they try to explain the properties of people in terms of physical properties of, when you get right down to it, matter. For one thing, holists claim that the influence of consciousness, their prime mover among variables, cannot be reduced to the jittering of mere specks of matter. If you’ve read this far, you know how wrong this is. The holists also object to the very idea of reductionism: viz., analyzing big things in terms of smaller things. Of course they do, they’re holists! And again, they say, quantum theory shows this is in an error because quantum theory tells us that all is one, and so there are no individual, separate entities in the world. When biomedical science proceeds otherwise-- thinking that big things consist of small, separate things—it is grievously in error. One day in my office at Delaware, I overheard a colleague in the next room, a colleague who did Asian things, discuss one of the pop physics books like The Tao Of Physics in a seminar of Honors students, and he said the same thing: we are all one big One. I felt like shouting that the IRS certainly thinks otherwise, and in case they are in error he can now pay my taxes. But let us imagine he was right, that it is all a Oneness as the holists say.

Nonetheless, scientists do very well by dividing the world up into distinct entities (e.g., mesons, electrons, quarks, etc.). You can’t even apply quantum theory unless you treat various systems as isolated and you describe systems such as atoms as having distinct parts between which forces operate. Even if Oneness is the truth of the matter, it is not important when it comes to explaining and predicting our world. What is important in all this: the Distinctness. The world behaves as if it consists of distinct entities, some localized in space/time, some spread around regions. Whatever the ultimate truth of the matter here, the distinctness hypothesis is nearly true and it is the only hypothesis that makes possible the activity of science and scientific understanding. Holists think that if things are distinct, then they must be unrelated. Of course this not true. Some also like to intone, contra reductionism, that everything is related to everything else, which they take to be a thesis akin to the Oneness thesis. It is hardly a profound idea that first falls out the quantum theory. It is the idea at work in Newton’s law of universal gravitation, and it isn’t until Einstein’s theory of general relativity that you arrive at a theory according to which some parts of the universe may not affect other parts.

In all this talk about how there are no distinct things, the holists show they don’t know the first principle of physics: viz., some relationships are more important than others, and thus some can be ignored when their consequences are small enough to be of no practical consequence, as when we may ignore effects from really spatially remote sources, and therefore dwindle in importance, other things being equal. Lastly, the holists’ appeal to quantum theory because they think it shows three big things about causality that conventional medicine disregards and thus falls into error because they do. Of course holistic medicine is said to be in line with these three things. The three things are: quantum theory shows us that causal relations cannot obtain between distinct entities or events, that each effect does not have a unique cause, and that causal relations are indeterministic, not deterministic. In their favored phrase, conventional medicine operates with a mechanistic idea of causation, and quantum theory contradicts that idea.

Where, as they say, to start? As for the idea that current medicine regards each disease as caused by one and only one factor: this is false, so false that to think otherwise is just plain silly. What are the causal factors in contracting AIDS? Not just one but many: e.g., hemophilia, homosexuality, promiscuity, IV drug use, being Haitian. And regular medicine proceeds to see if there is a common basis among such factors. In this case, it was that they increase the chances one transmits bodily fluids from one person to another, and if these fluids contain an infectious agent or agents, here found to be a virus, that makes for the disease, then transmitting such fluids is likely to convey the disease. In medical circles, they may say that the virus is the specific cause of this disease, but this is just a terminological habit; they just mean it is the factor that is a cause of one disease or condition and not others. The medical community concentrates on this factor because it is the ethical and effective route to preventing the disease. But make no mistake: the virus is a causal factor here as well the practices and living conditions cited just above, and also the frequency of transmission, the degree of exposure to the virus, and other factors varying person to person in the population we don’t know about.

Next, do the medical sciences use an incorrect deterministic concept of causality and ignore the fact, supposedly derived from quantum theory, that the whole determines the part instead of the part determining the whole? While quantum theory is indeterministic, this indeterminism is really small and of no import even at the micro-biological level. When you consider the famous Heisenberg Uncertainty relation—the relation used to, say, determine the position and momentum of electrons—you come up with probabilities, and thus uncertainty. It puts a limit on how precise we can be in predicting the simultaneous values of two variables that do not have a common eigenstate. These uncertainties are only of significance for really small objects. Applied to a 200 pound man, we can determine his position down to much less than a trillionth of an inch, and, simultaneously, his momentum down to much less than a trillionth of a pound-foot per square second. As things go in real life, this approximation is a certainty with regard to where the man is and how he is moving. True, some quantum effects are important to some biological effects; when that is the case, biologists do what they ought to do, they use quantum theory. Not to be outdone, the holists get quantum theory wrong when they talk about parts determining whole or vice versa. The whole universe does not determine whether the nucleus of an atom decays at a certain moment—nothing determines it.

Last but not least, does regular medicine makes a mistake in assuming there are any causal relations at all? It is odd that a holist would even imagine this was a mistake because holistic therapies are said, by the holists, to work -- and working is cause talk. Quantum theory does not rule out the existence of causal relations, but it does say that some subatomic events do not have deterministic causes, and also that sometimes causal relations should be construed as relations that increase and decrease the probability of certain effects occurring. This is not news; informed people in a variety of disciplines have proceeded along these lines for many years now.3:16: You include herbal medicine in your holism book, but there are anthropologists who say that where old tribal cultures have been using certain plants that in itself is evidence they must work to some extent. And are all holistic therapies as bad as the Simonton’s therapy claim to dream away your cancer or are there degrees of acceptability to you?DS: These anthropologists are presuming that if a group of people use a supposed medicinal substance for a time, then it works to some extent; and they would not use it otherwise. After all, who would use something that didn’t work? The answer has been plain since the dawn of time: tons of people. And there are lots of reasons why this is so, too: e.g., superstition, self-deception, stupidity, ignorance, bad reasoning, tradition, psychological factors galore, and, as always, plain old fraud. As reasons go, these are abiding and widespread. They are almost the human condition.

Perhaps an example or two will make the point vivid. Back in 1886, one William Radam patented his elixir Microbe Killer. He thought that all diseases were really only one disease, decay caused by fermentation, which in turn was caused by microbes. His elixir, then, was the one cure for all disease and much more. Radam was a gardener and florist in Texas, but his elixir sold so well that he ran seventeen factories to produce it. People all over America were using this elixir. Radam moved from Texas to a Fifth Avenue mansion in New York City. Around 1913, the government, seized a large shipment of the elixir and charged that its labeling violated the Shirley amendment to the food and drug act. This amendment made it illegal for a product label or package to contain false or fraudulent therapeutic claims. People were not only using Microbe Killer, but many thought it worked and had communicated this to the company. In one hearing, the defense lawyers produced 47 bound volumes of testimonials in support of the label’s therapeutic claims, and at trial they called a number of satisfied customers to the stand to testify that Microbe killer had cured them of cancer, tuberculosis, and diphtheria. A chemical analysis of the elixir showed it was 99 percent water and a one percent mix of red wine, hydrochloric acid, and sulphuric acid. It might prove something of a laxative and a stomach irritant, but that was all.

The history of patent medicine is a history of people using worthless tonics and thinking they worked to some extent. Back in the 1950s, one Dudley LeBlanc, a Louisiana state representative and patent medicine producer, had cranked his best-selling tonic Hadacol up to sales of 27 million bottles in a year produced by at least three factories; his advertising budget alone was sometimes a million dollars a month for print ads and radio spots. He also went on the road with a show that drew 10,000 a night. But he had learned from people like Radam. He kept his labelling free of therapeutic claims for specific diseases but testimonials said it cured all manner of medical problems from heart disease to epilepsy. When the authorities leaned on him for that, he kept the testimonial claims down to pep, energy, vague aches, nervousness, a bloated stomach. Hadacol was 12 percent alcohol, some B vitamins and minerals, and honey. It was little more than an expensive way to get drunk, that is, if you downed enough bottles. Again, lots of people using a supposed medicinal substance think it cured all manner of things, real and imaginary, to some extent. Turn on the television and you can still find the same thing with Extenz for male sexual performance, Prevagen for memory loss, Relief Factor for pain, and Balance of Nature as the way to keep yourself healthy. They let the testimonials and sales figures do the talking for the curative powers of their products. Who needs a real test when ads will do?

If anthropologists want to determine if some herbal is therapeutic, their first step should be to hand over a sample of the herb to an expert in pharmacognosy for analysis. The Simontons became popular through their book on how you can use visualization in treating cancer, Getting Well Again, which was published in the late 70s and that, by the mid-80s, had gone through 13 printings in hardback and eight in paperback. The Simontons want cancer patients to visualize their conventional therapy along with their immune system killing their cancer cells—imaging, as they put it, strong and active white cells destroying weak and inactive cancer cells, and also some sort of images standing for the conventional therapy doing the same sort of thing to cancer cells. I wrote a 50-page report on this therapy for the American Cancer Society’s committee that deals with unproven methods of cancer management. I was a member of that committee for five or so years, as I recall, in the 80s.

When you read the Simonton’s main book and their few papers in journals, their claims fall apart because they make mistakes left and right. Their error rate in their book is similar to that of Bernie Seigel and his book, which is also in the dream your cancer away business. Indeed, it is a knock-off. As for evidence, the Simontons present some cases studies in their book as well as report on an open-ended trial. You can be deal with both of these using a two by two table and the rules I have already discussed. When you add in some knowledge about clinical trials in oncology, especially ones that use historical controls, the Simontons look like amateurs at collecting evidence. Let me say a few things about the open-ended trial they present in their book and also in two journal articles. It appears that all three are concerned with the same patient population over virtually the same period of time. The Simontons have had patients entering their program since 1974, and one of their articles covers these patients for four years and the other one covers them for four and a half years, the same years here, 74-78.Their two articles actually report on just one trial. The book reports on this open-ended trial as well. The Simontons compare the survival time of their patients to the survival time of patients who received only conventional treatment at some prior time. They call these historical controls; in this case, literature controls because they were drawn from articles in cancer journals. The obvious question is whether the two groups are a fair comparison—similar in enough relevant ways to draw a conclusion one way other the other about this visualizing program. You can’t because the Simontons commit just about every error in the book.

For openers, when you compare survival times you need to know that the patients being compared all had the clock start at the same time; that is, survival from when? Date of diagnosis of cancer? Date of diagnosis of metastatic cancer? Date of entry in the study? In one article, they say, with respect most of the patients in the study, the starting point is the date on which they were diagnosed as having metastatic cancer. The Simontons are not in the diagnostic business, and their patients come from all over, having been referred after this diagnosis. The usual starting point is date of entry into the study. What were the starting points in the articles averaged to obtain their literature controls? They don’t say. Nor do they say anything about the survival times of around 40 percent of their patients, nor their types of tumors. How did they fare? And what kind of malignancy did they have? Nor do they tell us their conventional treatment both prior to and during the study. There are many known as well as unknown factors that that can affect survival, and so, in a non-randomized study, you need to check on whether the known factors in your two groups are comparable. Lots of factors can affect outcomes here, and they need to be comparable in your study and control groups. For example, there may be differences in how physicians select patients, how patients select treatments, as well as differences in prognostic factors (sex, age, performance status, tumor stage, etc.), diagnosis, staging, entrance criteria, supportive care, evaluation methods, and follow-up. These things need to be comparable in the study and control group, here the literature controls.

The Simontons fail to show that such matters are the same in their visualizing group and the amalgamated control group from journal articles—indeed, they do not compare their patients with the controls in any manner except survival. I looked up some of the articles they use as literature controls, and within five minutes found differences in histologic data on lung cancer patients and metastatic sites for patients in the control and in the Simonton study. Moreover, the Simontons fail to provide a lot of prognostic data on their own patients, and when they do, they fail to use this data in a comparative way. This is gross negligence on the part of amateurs, and is the Simonton trademark. Both of their articles were published in lesser journals, but neither should have been published anywhere. They do not meet one methodological guideline after another for reports of cancer clinical trials. I will spare you more details; they are in my report for the cancer society, which is no doubt in some file cabinet at their headquarters outside of Atlanta.

Now for your question: Are all holistic, crank, alternative, or complementary therapies as bad off as the Simonton approach when it comes to evidence? When I was on the Unproven Methods Committee, I gave a talk (with slides, of course, since the medical audiences expect slides) on how to classify the evidential standing of unproven methods of cancer treatment. This was at one of the ACS national meetings, this time at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. I was present along with about forty other members of the committee, liasons, consultants, and members of the American Cancer Society staff, all of us arrayed on the four sides of a rectangular arrangement of long tables put end to end and then nicely covered with a white table cloth. It was spiffy. After I spoke, two other members of the committee--one a professor of medicine from Vermont, the other attached to a hospital in upstate New York-- were to comment on my talk. At the time, the committee used a two-box setup, placing treatments into just two categories, proven and unproven for general use in the treatment of cancer. The “general use” phrase kept experimental treatments out of their unproven category because they were not for general use in the treatment of cancer. The term “proven” was used to mean well confirmed, or at least that. I thought the two-box setup was a poor one, and the purpose of my talk was to describe a better alternative.

To open, I said we at least need a three-box setup: viz., proven, unproven, and disproven. Vitamin C has been put to the test in two randomized, controlled clinical trials, both published in the NEJM and conducted by oncologists at the Mayo Clinic. In both trials, vitamin C failed to be an effective treatment for cancer. Thus vitamin C, as a cancer therapy, is not unproven but disproven. Back in the 60s and before, some chiropractors treated cancer by thumping on the spines of their cancer patients. We know more than enough about the human spine and nervous system to place this use of chiropractic in the disproven category. We know enough about chemistry (remember Avogadro’s number?) to place homeopathy in the disproven box as well, whatever you want to use it for. Ditto for immuno-agumentative therapy for brain cancer. Its molecules are too big to pass through the blood-brain barrier and so can‘t get into the brain. All well and good, so far. However, not all of the unproven therapies were equally unproven. That is, some were worse off than others, farther away from being proven, based on the alleged evidence to date. Just compare psychic surgery, the grape diet, laetrile, hydrazine sulfate, and topical BGN, a therapy I invented for the talk, bubble gum applied to the nose. There is more to be said for some as opposed to others, and I bet you could arrange them on a line running from least to say for them to the most to say for them, where saying here is summing up the existing, proffered evidence for each.

This shows we need to switch our figures of speech: viz., from boxes to lines. Indeed, two lines, one for safety and one for efficacy. The safety line would run from definitely shown to be safe to definitely shown to be unsafe, with degrees in between the endpoints. The effectiveness line would run from definitely shown to be effective to definitely shown to be ineffective, again with degrees in between the endpoints. The degrees—where on a line a therapy was placed—would represent how far the therapy was below or above being proven safe and effective. The idea was to place each therapy the committee dealt with somewhere on these lines so as to see, literally at a glance, where it stood from an evidential point of view. You could literally point to the therapy’s hash mark on the line, which would help out inquiring patients without going into all the details. Note that the safety line would take precedence, such that if a therapy was really unsafe, we would not need to consider its effectiveness. We would need to develop a classification system that incorporates the kinds of evidence (present or absent), the direction of evidence (for or against), the weight of evidence (a little or a lot), and an amalgamation of these features of the evidence into an overall or on-balance sum and connect that with hash marks on the lines. When I gave this talk, it was all the rage to score clinical trials for quality using one system or another. It was also common enough to see books tell you that the relative weight of clinical evidence, most weight to the least if properly done, went from clinical trial to cohort study, case-control study, cross sectional study, ecological study, animal experiment, and finally in vitro experiment.

Weighing medical evidence was in the air at the time, and so I thought we could make use of work already done and do further work such as distinguishing between a case series, case report case record, anecdote, testimonial, and single case experiment. I wanted to take about ten of the therapies on our unprovens list and, using the two lines approach, see how it worked using on some broad categories and simple ways of scoring evidence—a pilot effort, as it were, to scale up from. Both commentators were not optimistic about any of this. They thought it would be impractical if not impossible, there being too many things involved in evaluating and summarizing medical evidence. You couldn’t reduce it to a set of rules. They did not have any arguments for their naysaying, just claims that, to me, sounded like they wanted to spare members of the committee a lot of work unconnected with their nine to five jobs. It also reminded me of the debate over resorting to rules and formulas instead of clinical judgments in psycho-diagnosis, which became a big deal thanks to a little book by my teacher Paul Meehl at Minnesota. One member of the committee, an elderly physician from New Mexico, spoke up in defense of my idea. He said that he was amazed to hear his colleagues come out against logic.

That was it; nothing was done, or as the minutes of the meeting put it, no conclusion was reached. When I looked recently at the ACS website to see how things were going with my old committee, I could not find any trace of it or its work. The specific statements on therapies seem a thing of the past, and the committee doesn’t even seem to exist anymore. The website says some general things about alternative therapies and then refers you elsewhere for specifics, that is, the goods on particular therapies. They have farmed it all out. I did notice, however, that the general discussion talked about disproven alternative therapies, so the two box setup has at least gone to a three box one. However, that is miles away from lines representing where each of the twenty or so therapies we dealt with stood in terms of evidence about whether they were safe to use and worked.

3:16: You were the first philosopher to be on the American Cancer Society’s national committee, indeed on any national medical society committee anywhere, where you were writing reports on unproven therapies, weren’t you? How did that happen—and how useful was your philosophical background in doing this work? Were you bullshit detecting?

D.S: Soon after Examining Holistic Medicine appeared in 1985, I received a letter from an oncologist in St. Paul, MN. He was on the Unproven Methods Committee and had read our volume, and he thought I would a person who should be on the committee. He was writing to see if I wanted him to see about that. I agreed and then waited to see what he could do. He wrote back that he had tried to get me appointed, but could not. He found that membership on a national committee comes after years of volunteer work with the ACS, starting at the local level and then moving up the ranks. The more years in, the higher your appointments would go. I had no record of loyal volunteerism, but thought that I would be a very good addition to the committee since I had, by that time, become, whether I liked it or not, a real expert on this odd topic of crank medicine. It was not a hobby with me; it was my business. Perhaps some family friends could help out.

My father was a Mayo trained surgeon; in fact he got his M.S. while at the clinic and was trained by the Mayo brothers as well as other preceptors. Some of his early articles were co-authored with one Mayo or the other. My mother was a surgical nurse at Mayo then as well; they met there—she admired his suturing. When my father went into private practice where he was born in New York, he founded a surgical society that is still going strong today. Its membership, back then, was limited to those who had been fellows in surgery at the Mayo Clinic. They would travel each year to an academic medical a center whose faculty would put on seminars on their specialties for the society’s members. When I was a kid, I thought it was just a chance to travel someplace because the society was called The Surgeon’s Travel Club. When a member died, their spouse was still invited to the meetings because there were social events for spouses while the surgeons went to their seminars. Thus my mother and father knew lots of surgeons around the country, and I had met some myself. One of my father’s friends, and a member of the travel society, was chairman of the Department of Surgery at Penn, about fifty minutes by car from Delaware. They had both been Mayo fellows in surgery. He knew I had published an article on holistic medicine in the NEJM; I sent him a reprint in 1983, as I recall. He also knew about the holism volume. The publisher had sent him the page proofs, at my request, so that he could write one of those jacket and ad blurbs from a big name. I decided to see if he had any dealings with the American Cancer Society. He had, in fact he had been the President of the whole American Cancer Society for a term. He told me to send him a copy of the holism volume, which he in turn sent to the Senior Vice President for Medical Affairs of the cancer society, then headquartered in New York City.