Philosophising for Lost Souls

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I write this while self-isolating because of the coronavirus. Our President would like to believe that one could make it disappear by adopting a different conceptual system. I imagine him reading Foucault, Kuhn, or Quine for help.'

'Mozart’s forty-second symphony is a possible combination of notes that he hadn’t yet discovered. Possibility, this implies to me, is a mode of being, one complementary to actual states of affairs in spacetime.'

'Peirce chose the word “pragmaticist” to distance himself from James’s exuberance. One can be daring and decisive without believing that every girl wants your attention.'

'We’re not all dead; there are myriad choices still to be made in situations for which we are or shall be unprepared. Their abstraction—to whole, completed lives—begs the question: what to do now when nothing in one’s past decides the issue.'

'Equilibrium is the practical and moral demand on creatures that are socialized while having personal interests. Socialization requires our individual accommodation to practices that enables all to cooperate with others in pursuit of both individual and corporate goods (arriving at my destination while driving in ways that are safe for others and myself). This communitarian equation is skewed by its competitors: atomism and holism.'

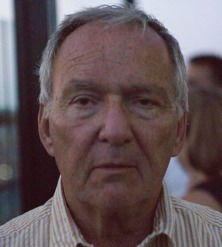

David Weissman's philosophic orientation is systematic, dialectical, and historical rather than phenomenological or analytic. He prefers Hegel and Peirce to Heidegger or Quine. He's written a lot. I don't ask him about art and cities here. Rather, he discusses what's wrong with atomistic metaphysics, what he'd replace it with, rejecting intuitionism and psychocentric ontologies, the contrast between enquiry and interpretation, his problem with Kant, comprehensive naturalism, silent conditions, eternal possibilities, illusions, norms and values, zone morality, freewill as a natural power, agency and evolution, equilibrium, and the need for autonomous individuals to be socialised.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

David Weissman: Often bored by detail or technique, I liked distance and the issues it clarified.

3:16: What’s wrong with an atomistic metaphysics of the kind you associate with Hume, Democritus, Aristotle, Jewish and Stoic thinkers, Luther, Calvin, and Descartes and what difference does it make to how we do metaphysics?

DW: Atomism ignores relations or regards them as accidents having no consequences for the character of the things related or their effects on others. But a sewing machine is more than a bag of parts, friendship is something additional to the people it relates. Spacetime is more than a passive container; relations it enables are responsible for energy-exchanges that promote stability, efficacy, and change.

Now add geometry and topology as they constrain these effects. Atomism is the false ontology fostered by the posits of our (too) simple analytic habit: whatever is distinguishable is separable. Hence our paradigms: Plato’s Forms, Descartes’ cogito, Hume’s impressions, individualism, and atomism.

3:16: So can you say what we should replace atomism with and how we should do our metaphysics – if metaphysics survives at all given that you put great stress on testability and there are those – Logical Positivists being the parade case – who decry metaphysics because it’s the sort of enquiry that can’t be tested?

DW: i. Distinguish active—causal—relationships—from those which are static: books on a shelf. Causal relationships are stable or ephemeral. The ephemeral include people passing, inconsequentially, on the street. The stable are systems bound by the reciprocal relations of their parts. Those reciprocities embody negative feedback, hence their tensile properties: they tolerate a degree of variation as their constituents evolve and alter their relations to one another. Systems disassemble when changes in their parts exceed the tolerance of their partners. From atoms, molecules, cells, and living bodies to states, systems are nature’s enduring substance. Nature is itself a system of gravitationally related parts, its stability conditions imperfectly known. Or should we suppose that all its constituent particles swim freely in a void where nothing is constrained?

ii. All of the above is empirically testable, though evidence is sometimes elusive.

3:16: You reject intuitionism and its psychocentric ontology. Can you map out its rough contours and say what its realist, fallibilist replacement looks like?

DW: Psychocentrism was implicit in Plato’s idea of nous, the cosmos seeing/thinking rational order within itself. Plotinus personified this when emphasized the power for individual self-reflection when knowing the Forms. Descartes gave the idea its modern impulse. We have never recovered the clear sense of creatures in nature when so many thinkers prefer to emphasize that nature is only what we think or imagine it to be, thinking of it when, all the while, conscious of ourselves.

Self-inspection displaces action, its aims, and context when we’re preoccupied by anxiety, self-appraisal, or aesthesis. But naturalists have resisted psychocentrism since the origins of Western philosophy. Their realism describes that context and our place within it.

3:16: You argue that since Locke and Kant you place a great deal on the contrast between inquiry and interpretation as part of your philosophical enquiry into meaning and nature. One procedure—inquiry—favors reality testing and truth. The other—interpretation—uses meaning to appease vulnerability and glorify believers. You say that much philosophical and cultural thought confuses them and yet they are often opposed and mutually hostile. Can you say something how they’re different and often opposed and why it causes muddle?

DW: I’ve slightly revised my way of distinguishing hypothesis from stories that bestow meaning/significance on alleged states of affairs. Both are interpretations, both allege that they discern or describe reality, but one makes testable claims about states of affairs, the other is valorizing: it projects significance onto real or imagined states of affairs. Having a partner or children is real; so is prizing them. But there is no evidence for the reality of one’s gods, apart from practices that affirm a belief. The faithful are, nevertheless, willing to fight and die for their beliefs. Their passion is real, but odd and misplaced: the issues are illusory; the disputes are veiled expressions of vanity (self-persuasion and esteem), interest, and power.

3:16: What do you mean when you say that something critical is missing in the accounts of experience shared by Kant, Foucault, Kuhn, Quine and other ontological relativists, as you call them? Does this link to your assertion that naturalism is deflating even though you claim that material nature exhausts reality as we do or can know it?

DW: Kant is the critical thinker in this list: reality so far as we can know it, he said, is a function of our ways of thinking it. How we think of it, he added, is a consequence of our values. Foucault, Kuhn, Quine, and others fill out this story, insisting all the while that reality is the projection of personal or social values or priorities. I write this while self-isolating because of the coronavirus. Our President would like to believe that one could make it disappear by adopting a different conceptual system. I imagine him reading Foucault, Kuhn, or Quine for help. Naturalism is deflating if one believes that life isn’t worth living apart from a grand meaning-bestowing narrative; though not if one has aims, relationships, and sensibilities gratified by other people, work, sport, nature, or whatever. We’re accustomed to fantasies having no basis but our vanity: “created in God’s image.” We might learn not to want or need them.

3:16: Can you give an oversight for us of your notion of comprehensive naturalism anticipated by Aristotle and Spinoza: "natura naturans, natura naturata" whereby nature naturing is an array of mutually conditioning material processes in spacetime?

DW: I falter when satisfying this demand because my understanding of nature is too shallow to satisfy the diversity, depth, and detail of scientific understanding. My best approximation is a figure representing the trajectory of emergent systems in spacetime: from atoms and molecules to cells, bodies, tribes, and states. There are generative laws regulating the processes creating these successive emergents from their lower-order constituents (triangles from line segments), and descriptive laws (of physics, biology, and sociology) applicable within their separate domains. These processes create all the complexity we embody, see, and exploit. All the rest is a projection. For we live in these two domains: nature and the worlds of fashion, entertainment, loyalty, and religion. Many people have commended gardening as a powerful distraction.

3:16: You think nature has conditions that will likely remain unknowable but absence of justifying empirical data entails that speculation doesn’t justify belief. What are the ‘silent conditions’ you discuss, and why are they significant if we’ll never be in a position to believe them?

DW: It’s not unlikely that there is more to reality than is accessible to creatures reduced to using acquired, now innate, rules of inference to process sensory data. We speculate about those conditions. Are there gods? Unlikely, because the roles assigned them have other, better confirmed explanations. Was there a Big Bang, and perhaps an infinite history preceding it? More likely. Are actual states of affairs prefigured by the eternal possibilities that Wittgenstein described as the facts in logical space? I agree with him, Leibniz, and some others that this is so. Why? Because I can’t find a way of defeating this inference: whatever is not a contradiction is a possibility; hence either a possible or a contradiction. There are, this implies an infinity of possible worlds distinguished from our world by their signature natural laws, and an infinity of variations within each of those possible worlds. Mozart’s forty-second symphony is a possible combination of notes that he hadn’t yet discovered. Possibility, this implies to me, is a mode of being, one complementary to actual states of affairs in spacetime. This is a modal Platonism, one in which the possible are known only when instantiated or when signified. Though they are, nevertheless, the backdrop to all that is. Or, for a phrase, signification doesn’t create the possibilities signified. Is there more we don’t know but could, perhaps, infer? Dark matter or energy, for example. Perhaps. Should we be uncomfortable cause unable to discern all that environs or makes us as we are? We respond by speculating: what can we imagine? But then we err, if we confuse that power with confirmation that things imagined do obtain.

3:16: So you argue that reality extends beyond nature to what you call ‘eternal possibilities’. What do you mean by eternal possibilities – why eternal and how can a possibility have any reality or play any causal role at all? And how does Wittgenstein’s Tractatus come into this account?

Eternal possibilities are inferred: nothing is if it isn’t possible. But possible are a version of formal, not efficient cause. They anticipate without themselves being instances of that they prefigure: the possibility for circularity isn’t a circle. This is a dialectic already implicit in Plato’s Forms: the Form of Beauty isn’t beautiful. The dialectic isn’t, I agree, satisfying or resolved. But reality doesn’t reduce to all that is. Or one argues with Spinoza that ours is the only possible world because all within it is necessary, and because every alternative is impossible because of inherent contradictions. This last claim has never been confirmed. Probably the moon couldn’t have adhered if made of green cheese, but there is no contradiction to supposing that it, in a different possible world, could have been larger or smaller, differently colored or cratered.

3:16: Why don’t you think illusion, construction and theism can be substantiated by logical or empirical evidence and why value the value of sobriety in the conduct of practical life as Dewey recommends? Would it be right to see your work as influenced by Pragmaticism?

DW: i. It’s not that I think illusions can’t be substantiated by logical or empirical evidence; rather that no one has ever succeeded in using either to substantiate some principal illusions. The idea of democracy is a delusion in the minds of autocrats, but one vindicated by education and practice. Other beliefs—of divinity or racial purity--don’t fare as well. People try; they end up confirming what they believe by citing other believers or the books to which believers defer. Add that practical experience and science provide substantial confirmation for the belief that nature has an integrity that makes one skeptical of the sketchy stories illutionists tell.

ii. I was a pragmatist before reading Peirce and Dewey. They affirmed the consequentialism and sobriety to which I’m inclined. Peirce chose the word “pragmaticist” to distance himself from James’s exuberance. One can be daring and decisive without believing that every girl wants your attention.

3:16: You’ve looked into the nature of norms and values and argue that norms are discovered as well as made, and inhere in the circumstances that constrain us. How do you understand this natural normativity – does this link with your idea of truth’s debt to value, that results in the view that we must respect the integrity of a world we have not made and find our way within it with the help of attitudes and desires that have been informed by truth.

DW: Natural normativity is everywhere: in cycles and processes we can’t alter and in those we learn to control. Traffic laws are norms of a different sort: we make and change them as their use and effects justify. We stand on these two feet: one is the informed reading of our circumstances: where are we; what do they require? And the other: how do we best regularize personal and social practices, given the latitude nature provides? We are consequentialists by nature, always acknowledging natural norms as they constrain the domains of human choice.

3:16: In terms of morality, you’ve introduced the notion of ‘zone morality’. What is this and how does it differ from the usual emphasis placed on moral theories?

DW: It seemed to me that dominant moral theories, Kant’s especially, lack nuance: we can’t declare for all circumstances what is appropriate to some. Zone moralities are contexts distinguished by their constituent relations: self-regard; loyalty to family or friends; vocational or commercial relations; or one’s relations to anyone with whom one shares a sidewalk, a state, or humanity. Virtue moralities could cover these distinctions, but they aren’t usually differentiated in ways appropriate to these differences. Kantian moralities are too quick to generalize while abstracting from pertinent differences; the zones are vaporized when the demand for universalization erases every difference.

3:16: You argue that free will is a material power, not the conclusion to a conceptual argument, and that having it makes us morally responsible for much we do and prefigures our moral identity. So can you sketch for us first how free will developed naturally and how autonomy and responsibility survive when both are eclipsed by ideas that embed us in history or tradition. In particular what are the four elements that you argue together combine to defeat the Laplacian determinism that claims that an agent’s responses are merely responses according to laws and original conditions?

DW: I understand free will as having complementary conditions: one structural, the other functional. The structural condition evolved, I suggest, from the primitive power of inhibition. Cell walls or exoskeletons enabled primitive creatures to resist intrusions or to inhibit responses. And critically, these barriers created internal spaces in which more discriminating faculties—deliberation, for example-- could evolve. Those faculties empowered choice: squirrels could decide where to look for nuts. Weren’t their choices determined by a lengthy history of antecedents? Perhaps But now add this functional consideration: humans and some other creatures face circumstances that are often unanticipated, circumstances in which alternate responses would be reasonable in themselves. Add that the array of acceptable responses is limited by an agent’s interests and values, and that nothing in one’s past determines which response is preferable. This is the place of deliberation, choice, and free will. Such choices are not unconditioned; many antecedents have determined one’s posture in these circumstances. Freedom lies in the fact that the final determining cause—what to do given an array of possible actions—is the deliberation (however brief) that terminates in choice and action.

A bibliographical point: my essay, Autonomy and Free Will, makes the functional claim. Chapter two of my book—Agency—introduces the structural claim as its complement.

Hard determinists argue that one consider the causal integrity of a life-time. Arguments like mine ignore that integrity by imagining that causal lines could have diverged within life-times. That, say those determinists, entails lives an array of possible lives different from those actually lived. But the error is theirs: they deny time and process. We’re not all dead; there are myriad choices still to be made in situations for which we are or shall be unprepared. Their abstraction—to whole, completed lives—begs the question: what to do now when nothing in one’s past decides the issue.

ii. Laws and original conditions. Modern philosophers (since Hume) cite laws without explaining their locus in nature. Do we mean regularities, because if so, they supply too little basis for securing the causal lineages vital to hard determinism; do we mean the sentences in well-confirmed theories? Laws are sentences? That’s a version of the conceptualism that deprives hard determinism of any ontological weight. What do we imply by original conditions: some array of differences in the soup qualifying spacetime before the Big Bang, or capacities that would evolve in the linear ways required by hard determinism. Add that hard determinism doesn’t distinguish Leibnizian holism from the independence of causal streams established by decoherence (the breakup of the dense whole inferred to have existed before the Big Bang). Consider those independent streams: you and me. Is my response predetermined when you ask me a question for which I believe myself to be unprepared? That would imply the Leibnizian idea of pervasive internal relations: you and I are already bonded in every detail, however mutually unaware prior to this momentary encounter (“Is this the way to Broadway.”). Suppose instead that my response isn’t predetermined—we aren’t bonded—for then I can deliberate before responding deliberately and coherently, but tentatively: “Where are you trying to go?”

3:16: Can you explain what you mean when you say that agency is an evolutionary experiment and what’s its relationship with the notion of equilibrium?

DW: Life needn’t have emerged; creatures that preserve and satisfy themselves needn’t have evolved. There are, I assume, none on Mercury or Pluto. Equilibrium is the practical and moral demand on creatures that are socialized while having personal interests. Socialization requires our individual accommodation to practices that enables all to cooperate with others in pursuit of both individual and corporate goods (arriving at my destination while driving in ways that are safe for others and myself). This communitarian equation is skewed by its competitors: atomism and holism.

15. Why do autonomous individuals need to be socialized if they are to be moral agents?

DW: The first of the four zones is self-regard. Socialization wouldn’t be an issue if one were alone in the world. That is implicitly the idea of Robinson Crusoe and Locke’s remark, “In the beginning when all the world was America,” meaning a vast wilderness where one could be alone. Though an isolate would address a principal moral question: who, what shall I do or be? What idea of myself directs me? Socialization complicates the issue because one is formed by others and responsible to and for them in ways that often occlude or foreclose personal choices. Hence the four zones and the degrees of freedom implied by moving within and among them.

16. And finally for the readers at 3:16 are there five books other than your own that you can recommend to take us further into your philosophical world?

DW:

Plato, The Republic;

Aristotle, Metaphysics and

Spinoza , Ethics;

C.S. Peirce, Collected Papers, Volume 5;

Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-philosophicus;

and (a sixth) Dewey, The Public and its Problems.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes