Philosophising Under the Shadow of God

Interview by Richard Marshall

'My own current take on the analytic-Continental divide is more pluralistic than simply saying: here’s a watershed on one side of which people embraced the Fregean revolution, on the other they didn’t; either people stuck with Kant or they went down the path to perdition with Hegel. Schelling (of all people) has a brilliant remark where he contrasts “transcendental philosophy” and the “philosophy of nature”. Transcendental philosophy, he says, tries to discover the ideal in the real, while the philosophy of nature tries to explain the ideal from the real. It seems to me that, mutating the mutandis, this is a pretty good account of what divides philosophy and philosophers today.'

' It’s been a life-long obsession of mine to try and understand the irrational in politics. As someone who has grown up in the shadow of the Nazi genocide how could one not find that to be an urgent and pressing problem? Obviously “false consciousness” has been a theme in philosophy and religion for as far back as we can trace them in the Western tradition. What is distinctive about the theory of ideology, though, is that it aims to explain how unjust, oppressive, prima facie illegitimate, societies persist through mechanisms of false consciousness. It’s not people adapting to the overwhelming superiority of force of those in power but people adapting themselves in other ways to circumstances they find themselves in.'

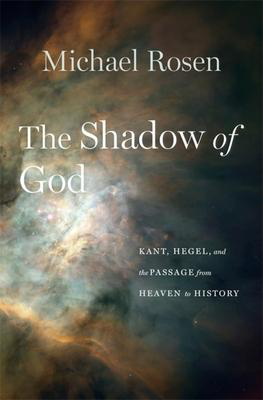

'In the narrative of The Shadow of God Fichte is absolutely key. In his Lectures on the Scholar’s Vocation he picks up Kant’s idea of the Church Invisible, that humanity is engaged in a joint project of the realization of justice, and makes it into a this-worldly conception of historical immortality. What matters about human beings is not their material existence, which is finite, but the part they play in the shared project of human self-realization. Similar ideas are around elsewhere at that time, for example, in Herder, and in Saint-Just, when he says that he “despises the dust from which he’s born” but that he lives for posterity. One of the main objectives of my book is to make it clear how far this idea of “historical immortality” is part of the ether of modernity.'

Michael Rosen is a professor of political theory in the Government Department and has worked on a wide variety of topics in philosophy, social theory and the history of ideas. He is particularly interested in 19th and 20th century European philosophy and in contemporary Anglo-American political philosophy. Here he discusses the continental/analytic divide, different explanations for this divide and his own view, Kant as an inside-outer, rationalism, the influence of Kant, the irrational in politics, ideology, false consciousness, Hegel, Geist, the Enlightenment's stunted view of rationality, Fichte, Marx and ideology, a revisionary religious Kant, God and metaphysical freedom in Kant, self-givenness, the Lisbon earthquake and the question of evil, punishment and Kant, theodicy in Kant, Nietzsche, Kant's natural religion, the possibility of history as acting as a redemptive telos, Schleiermacher and Swedenborg and Kant.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Michael Rosen: I came to philosophy inadvertently. I’d studied modern languages and economics at school but I knew I didn’t want to become a linguist so I came to Oxford to read PPE. Philosophy was thrown in as part of the package, but the philosophy I was first confronted with in Oxford didn’t appeal to me. What I now understand is that things that had been of great interest to me as a teenager, even though they weren’t officially “philosophy”, somewhat blocked me from seeing the philosophical world in the way that my teachers in Oxford expected me to see it. As a teenager, I was taken by writers like Marshall McLuhan, George Steiner , Robert Graves , Aldous Huxley, E.H. Gombrich. They conveyed a sense that, as you go through history, moving from culture to culture and looking at art and literature as well as politics, you’re not working on a single scale. I thought that it was obvious that we encounter the world through cultural matrices.

So I suppose I was a kind of kneejerk Neo-Kantian historicist without knowing it. Philosophy is a holistic subject and, when you introduce people to it, there are always things over the horizon that are taken for granted – in this case a picture of the philosophical world as divided, roughly speaking, between empiricism and positivism on the one hand and ordinary language philosophy on the other. I didn’t recognize myself in that and so I felt unsympathetic and disoriented, despite having kind and generous tutors. I kept going at least in part because I was very drawn to the foundational and methodological questions that were implicit in the economics and politics that I was also studying, but it was only when I came to read Kant and the Critique of Pure Reason that philosophy as taught at university drew me in and excited me.

3:16: Wasn’t Marxism fashionable then amongst students like yourself? Didn’t you get drawn to Marxism at the time?

MR: I was always more of a hippy than a Leninist (I still am, I suppose) but I wasn’t totally immune to it. I wasn’t totally immune to it. Around that time Radical Philosophy was founded and I used to go to their meetings and talks. But Radical Philosophy wasn’t simply Marxist and, of course, what it meant to be a Marxist philosopher wasn’t clear either. My own trajectory towards and then out of Marxism is complicated but I always had a strong sense of its limitations and difficulties. There was certainly a time, though, when I thought that, if only I could get myself clear on Hegel, I’d get myself clear on Marx and be able truly to make myself comfortable in Marxism. I can now see that an important part of my early career was coming to the conclusion that the things that had made me uncomfortable in Marxism were not distortions that had been imposed on it by later thinkers but were actually inadequacies in the original Marxist project.

3:16: So what was Marxism in Oxford at that time?

MR: In Oxford? It was hardly very significant. The Radical Philosophy Group was mostly made up of graduate students, many of whom did not see themselves as Marxists even then (for example, Peter Singer and Jonathan Ree). Those who did think of themselves as Marxists divided into Lukacsians and Althusserians. I was never tempted by Althusser (although I was a fan of Maurice Godelier and of French structuralism) but I was drawn towards Lukacs, filtered by my reading of Alasdair MacIntyre.

3:16: So there is this supposed divide between the Continental and the analytic and some people say it does cut philosophy at the joints whilst others say it’s just a sociological thing and then there are people who seem to count as Analytic Continental people so it seems a confusing landscape. I wonder if you could help us navigate this?

MR: Well, I do have a lot to say – although it may or may not clarify things for you! It’s an issue I’ve been thinking about for a long time, but I’ve changed my mind somewhat over the years. And I also think the landscape itself has changed in that time. One of the first things to ask about dividing the analytic and Continental traditions is: at what point do you think they separate? There are two answers. One is to say that analytic philosophy started with Frege and “Continental” philosophy is what was left behind; the other that the divide comes after Kant (Oxford used to have a paper called “Post-Kantian Philosophy” which covered Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger and so on). The narrative that has the parting of the ways with Frege is puzzling. After all, Frege’s project was the reduction of arithmetic to logic, which, by common consent, didn’t succeed, although it did lead to the invention of the predicate calculus. But then a disrespectful person might say: OK, the logicians have got a new calculus and they can use that to extend the representation of deductive inference. But what’s the philosophic importance of that?

3:16: Good question!

MR: One explanation – obviously an important one – is that logical analysis enables us to go beneath the surface of language, which seems to have a subject-predicate structure, and, by employing the representational tools of functions and arguments, get to what really underlies it and thus make progress with the grand project of formalizing natural language. But who now identifies analytic philosophy with the project of reconstructing the semantics of natural language on the basis of formal logic? Only a very, very small number of philosophers, I suspect. The high days of Dummett and Davidson have ended. Philosophers of language these days, so far as I can see, have re-tooled themselves as people who talk about conversational implicature, pragmatics and so on and so forth – in fact, just those interactive, context-dependent, rhetorical parts of language that the Fregean-Russellian-Tractarian project was supposed to cut through.

The alternative narrative makes the break with Kant. But the idea that some kind of a break happened immediately after Kant is a modern artifact. In the nineteenth century, when German philosophy was such an enormous force in British and American philosophical and social thought, Kant and Hegel were read together and contrasted with Locke, Hume and Mill and the empiricist tradition.

One person who does tell the story that way is Popper. Kant, for Popper, is a pioneer in approaching the world in a theory-laden, interpretive but experiential, “non-metaphysical” way. So, for him, the Kantian “Copernican revolution” was about appreciating that we look at the world through categorial spectacles. Admittedly, Kant thought the categories were once and for all, but a more correct understanding meant that, thanks to Kant, the once-and-for-allness that had afflicted philosophy for so long could itself be overcome. Hegel, on the other hand, was a philosophical reactionary, trying to re-establish the hegemony of metaphysics in a total system.

3:16: So what do you make of this narrative?

MR: This is a powerful narrative, so powerful that it has even been extended to include Hegel himself. For “non-metaphysical” interpreters of Hegel, Hegel, like Kant, believes that our engagement with the world is always conceptually mediated and the only reason that he sounds like a metaphysical realist is that he’s taken anti-realism to its conclusion, to the point of getting rid of “things in themselves” entirely. But, in my view, that narrative is wrong, not just about Hegel but about Kant too. It’s basically a Neo-Kantian take on Kant. The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century was a time of enormous philosophical ferment and crisis even for those who didn’t follow Frege, particularly so for philosophers who had been Kantian in their approach. After all what had Kant argued? He argued that philosophy showed not only that Euclidean geometry was true, it was necessarily true and necessarily applicable to space and time. So that looks like an extraordinary egg-on-face moment for philosophy.

Neo-Kantianism became a sort of “yes-but-no” Kantianism. Kant was identified, not with a set of metaphysical claims to give synthetic a priori truths about nature and science, but with a “turn to experience” that set “transcendental philosophy” in opposition to “metaphysics”. Kant’s synthetic a priori wasn’t thrown away completely, though. Thus you have Cassirer, where these synthetic a priori frameworks are themselves changing historically. And Popper too was a kind of Viennese Neo-Kantian. But you only have to look at the titles of Kant’s own books ( Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics , Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science , and so on) to see how much of a revision that was and that Kant thought of himself as a metaphysician (although a “critical”, not a “dogmatic” one).

3:16: So where do you stand on this?

MR: My own current take on the analytic-Continental divide is more pluralistic than simply saying: here’s a watershed on one side of which people embraced the Fregean revolution, on the other they didn’t; either people stuck with Kant or they went down the path to perdition with Hegel. Schelling (of all people) has a brilliant remark where he contrasts “transcendental philosophy” and the “philosophy of nature”. Transcendental philosophy, he says, tries to discover the ideal in the real, while the philosophy of nature tries to explain the ideal from the real. It seems to me that, mutating the mutandis, this is a pretty good account of what divides philosophy and philosophers today. Some are “naturalists” and do philosophy “from the ground up”, while others are “phenomenologists” and do it from the inside out (although some try, like Schelling, to do both). Of course, very few people have the extravagant idea of nature that Schelling did, so contemporary naturalism isn’t usually a story about the world-soul or the conscious universe, but the structure of enquiry is the same.

As for doing philosophy from the inside out, Hegel has a famous saying in the Preface of the Phenomenology : “what you’re acquainted with you don’t necessarily recognize.” The idea that philosophy is about bringing to consciousness something that is latent in your intellectual world goes back to Plato, of course, but pure “inside-outers” are more typical of Continental philosophy while there is a much stronger streak of naturalism running through analytical philosophy. To my mind, that’s a more helpful way of trying to understand the differences. It doesn’t exactly track the geographical and historical differences, but that is, I think, an advantage: it explains why there are affinities across the traditions.

3:16: Doesn’t that make Kant a problem?

MR: I argue in The Shadow of God that he is an “inside-outer” – he says in the Preface to the first Critique that metaphysics (note the word!) is the inventory of our possessions produced through pure reason. There are also many analytical philosophers who would count as inside-outers – Wittgenstein is the most obvious. He has a quote that is almost exactly the same as Hegel’s and even Rawls would count, with his idea of reflective equilibrium. I should add, though, that running through the Continental tradition along with what I’ve called this “inside-outism” is the search for a higher conception of reasoning than you find in simple understandings of logic and the empirical sciences. It’s that German distinction between sense , understanding and reason . This is tremendously important for pretty much everyone you would think of as being a central figure in the Continental tradition. Even, Heidegger, who is not a believer in reason with a capital “R”, believes in a kind of hermeneutic truth that can't be captured in the methods of science and “the understanding”. Hence there is a very strong anti-positivist presumption running through the Continental tradition, if by “positivism” you understand giving authority to the methods of science (physics, in particular) as norms of rational enquiry.

3:16: Okay, so what are what are philosophers up to?

MR: Well, obviously, lots of different things! A question I’d find easier to answer, if I may humbly suggest, is to ask, inasmuch as you think of yourself as a philosopher, what do you think you are doing? And for that, I need to say that I see a broad and a narrow sense of philosophy. In a broad sense, philosophy is about everything of an ideal or cultural nature that helps us find our place in the world. That's a kind of super-broad Hegelian conception: that philosophy is engaged in the ‘project of reconciliation’, as Michael Hardimon has wonderfully called it.

From that point of view, anything that touches on our place in the world – questions of life, death, satisfaction, despair, moral agency, mutual respect – is part of philosophy. And it doesn't really matter if it's something taught to students by people who are in a philosophy department or reflected on and written about by people who are not. I see them all as part of that shared enterprise and as needing to be studied and thought about together. But then there are more restricted conceptions of philosophy, things that are given their identity as “philosophy” by being part of a historical tradition. In my very broadly Nietzschean understanding of things, we in the West are the inheritors of a philosophical (and religious) tradition in which the “project of reconciliation” and the “project of justification” have been intimately interwoven. And we have come to a point at which we see these may be very different things; we may have to choose which one we want to adhere to. We can't, in my view, make the rationalist assumption that in the end, the two of them will come together.

3:16: So you’re pessimistic about the rationalist assumption?

MR: Well, I should make it clear that “rationalism” can also mean different things. By “rationalism”, I don’t just mean a commitment to rationality but the conviction that realizing rationality (whatever exactly that might amount to) will bring reconciliation with it. That kind of rationalism runs from Plato to Hegel to Marx and Habermas. It’s that that I’m sceptical about. I finish The Shadow of God with a quote from Orwell: “‘The truth is great and will prevail’ is a prayer rather than an axiom.”

3:16: So why is Kant so influential?

MR: There’s no single reason, of course. He was influential in different ways at different times. Certainly, he had a great impact on his own society right from the start. Part of the explanation is sociological: the German universities produced an educated public – lawyers, doctors, priests, teachers, administrators, as well as aristocrats and soldiers – who read and thought seriously about philosophy. But there’s more to it. Fichte notoriously took on a job to teach Kant before having read him and then, when he did read Kant, felt the scales fall from his eyes. Why? Because he’d felt threatened by Spinoza’s fatalism and feared that, if you were going to be a rationalist in some broad Enlightenment sense, you couldn’t at the same time believe in human agency and freedom. Kant allowed people to believe in human agency and freedom without falling back into the dogmas of revealed religion or rejecting causal science.

So Kant’s philosophy (his rational religion included) steers a path between scepticism and dogmatism: the dogma of doctrinal authority and the scepticism about human agency and moral responsibility that comes from looking at things from a naturalistic perspective. Of course, one way of representing Kant’s originality, as I’ve already mentioned, is that he was a critic of metaphysics: if only he’d dropped the thing in itself he’d have been on the way to being Peirce or Sellars or Brandom. That isn’t the way I read Kant, though. So I think his originality is elusive. I think a great deal of it is to do with the relentless drive for justification which runs through and holds together his metaphysics, moral philosophy and account of religion. In a certain way that’s Kant reconfiguring the Enlightenment as it had existed before him so he can see himself as its epitome. That is the Kant I try to present in The Shadow of God .

3:16: So what did he see as wrong with the Enlightenment?

MR: Oh, a great deal. Sentimentalism – reducing morality to feelings – Spinozism, determinism, naturalism. Those themes had no appeal for him whatsoever. On the contrary, he felt he had to oppose them while still defending both science and human agency. That’s what makes Kant Kant.

3:16: OK, now we’ll return to Kant and the new book but as a lead in let’s look at an earlier preoccupation of yours, ideology, because this will give us some extra ideas about your understanding of Kant and Hegel. Can we start with your thoughts about false consciousness and Reich’s question about why people believe things that aren’t in their best interest?

MR: It’s been a life-long obsession of mine to try and understand the irrational in politics. As someone who has grown up in the shadow of the Nazi genocide how could one not find that to be an urgent and pressing problem? Obviously “false consciousness” has been a theme in philosophy and religion for as far back as we can trace them in the Western tradition. What is distinctive about the theory of ideology, though, is that it aims to explain how unjust, oppressive, prima facie illegitimate, societies persist through mechanisms of false consciousness. It’s not people adapting to the overwhelming superiority of force of those in power but people adapting themselves in other ways to circumstances they find themselves in. So that’s the beginning.

3:16: Is it false because they’re wrong to think what they do, or is it wrong because they don’t realize they’re doing what they’re doing?

MR: The answer comes in many forms. It’s a German sense of “false”: that is to say false to some conception of what it is reasonable to think (or, indeed, feel) rather than false just because it is a belief that fails to reflect a realm of neutral facts. So people who are alienated suffer from “false consciousness” even if they see the world in factual terms more or less as it is. The challenge was to try to analyse and understand different forms of false consciousness. You can see false consciousness as amour-propre , a kind of vanity that leads one to flee from the realities of the human condition. You can see that in Pascal. That’s a false consciousness of a theological-ethical sort: human beings’ avoidance of the wretchedness of the human condition by a sort of distraction and turning away from religion. It’s not in and of itself something to do with a particular oppressive society.

But in Rousseau’s hands it becomes closer to social oppression because he thinks of it as a kind of vanity that is also public. It’s not just the vanity of wanting to put on a good front in public, though, but the vanity of seeing yourself – identifying yourself as we now say – with who you’re seen to be. In a society in which what counts is who you are seen to be, it becomes very easy for that to be manipulated in others’ interests. The main thrust of On Voluntary Servitude is that the theory of ideology emerges from the confluence of two ideas. The idea of “false consciousness” is brought together with the idea of society as having the ability to reproduce itself systematically. For Rousseau, who didn’t really have that second idea, the critique of false consciousness is powerful in and of itself because it leads people to a kind of distance from themselves – as he puts it, people no longer resemble themselves. That would be a reason to criticize modern commercial society even if it were not benefiting some elite.

3:16: Where does Hegel fit in to this?

MR: Not everyone would say that Hegel had a theory of ideology because he didn’t see human beings identifying themselves with their society as in any way wrong. He’d say that was inevitable and right. Even a viciously authoritarian and unequal society, if it endures, has a “general will”, he says. But that general will, that development of Geist , has something to do with the theory of ideology because it works through human beings’ immediate and intuitive grasp of their own culture, rather than through rational justification. So, although Hegel does think that it is rational for people to identify with their society, it isn’t through rational justification that they do so.

3:16: What’s this key word “ Geist” , often translated as ‘Spirit’ in English? Is it referring to something that’s supernatural?

MR: It’s an amalgamation of different ideas, ideas which you wouldn’t normally think of as going together. It’s the Christian triune God. It’s also Spinoza’s God, that’s to say, the one true substance. It’s also the Greek/Christian idea of the logos , the idea of an underlying, rational order running through the world. And it’s also a kind of Schellingian world-soul, the idea that at the ultimate level we shouldn’t just see the world as matter in motion, the unfolding of some ultimate causal processes, as Spinoza would have it, but as a kind of organic self-realization. <em>Geist</em>is all of those things. You could say that it is both natural and supernatural.

3:16: But I thought the Enlightenment was trying to get away from all this.

MR: Yes, that’s a good point. If Hegel is truly a successor of Kant and Kant is, as I’ve claimed, the epitome of the Enlightenment, how can that be? It does make sense, though, if you remember two things. Hegel’s project, as he understands it, is a rationalistic one. It takes up Kant’s idea that any elements in religion that can’t meet the test of rationality have to be discarded. Although Geist corresponds (and is meant to correspond) to the Christian idea of God, Hegel’s conception of religion is purged of elements of arbitrariness, miracle, ecclesiastical authority or direct revelation. Also, by the way, a Last Judgement and an afterlife. But fortunately, Hegel believes, reason is a great deal more capacious than Kant realized. Hegel thinks the Enlightenment has a stunted notion of reason and he thinks part of the problem with Kant is that he limited himself to that conception – although there were places, particularly in his moral philosophy, where he saw that you couldn’t restrict reason in that way.

3:16: What was so stunted about it?

MR: To explain, let’s go back to the structure you find in Kant. For Kant, thought and the mind are divided into three main faculties: sense , understanding and reason . Empirical judgments involve both understanding and sense. One is the faculty of concepts and the other is the faculty of intuitions. Concepts without intuitions are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind, as he writes so famously. This is central. So where does reason – “ Vernunft ’ – come in? As far as the theoretical realm goes, it’s a set of ideals, organizing principles, not itself a source of substantive knowledge. It is however a source of substantive knowledge in moral action.

If you want to be very crude about what comes after Kant, the post-Kantian German Idealists thought that Kant was right about reason being a source of substantive knowledge in moral agency and that, once we understand that, we can see how reason can also be a source of substantive knowledge much more generally. That’s the trajectory we get as we go from Kant to Reinhold to Fichte: the idea that it’s not enough to have a classification of the mind into reason, understanding and sense, we need something foundational to hold it all together that can’t itself be part of the system of judgements. It has to be, as Fichte says, a sort of intellectual deed , rather than a perception or an act of judgment.

3:16: So it becomes something you do.

MR: Yes, although not in the sense of a practical intervention in the material world, although that is a very common misreading. Fichte’s conception of agency is super-abstract. There’s an insight that Hegel and Schelling got from Hölderlin which says that, once you’ve understood the “I” in Fichte as fully active, once you’ve purged it of everything empirical or psychological, it becomes equivalent to Spinoza’s God.

3:16: Which is the opposite of what Fichte was wanting wasn’t it? Wasn’t Fichte arguing aganst Spinoza?

MR: I think that there are two things the Idealists saw in Spinoza. One was a fatalistic determinism within the world, and that they certainly rejected; but the other was a picture of the world as a whole as a single substance, the “ hen kai pan ”, and that they did very much endorse. And I don’t think that Fichte was so far from that second idea.

3:16: So Fichte is important?

MR: In the narrative of The Shadow of God Fichte is absolutely key. In his Lectures on the Scholar’s Vocation he picks up Kant’s idea of the Church Invisible, that humanity is engaged in a joint project of the realization of justice, and makes it into a this-worldly conception of historical immortality. What matters about human beings is not their material existence, which is finite, but the part they play in the shared project of human self-realization. Similar ideas are around elsewhere at that time, for example, in Herder, and in Saint-Just, when he says that he “despises the dust from which he’s born” but that he lives for posterity. One of the main objectives of my book is to make it clear how far this idea of “historical immortality” is part of the ether of modernity.

3:16: And is still recognizable in some parts of the artistic avant-garde tradition.

MR: It’s there in our culture. We don’t live in a world from which religion has disappeared – that would be a ridiculous thing to say – but there was a radical transformation and new forms of collective self-identification arrived. Unfortunately, the inclusive universalism about history that we find in Fichte in the 1790s disappeared and he became a nationalist. Still, he was a nationalist of universal purpose, as many nationalists were, who saw their nation – in this case, Germany – as the saviour of mankind. Which makes it pretty dark.

3:16: Returning to ideology, following Hegel we have Marx. You think his theory is flawed, don’t you?

MR: In my view, Marx hasn’t got a theory of ideology. He’s got different models and those different models have different objections to them. Even in The German Ideology , he’s got two different ideas. One is what I call the “reflection” model, the famous metaphor where he describes ideas in society as like being in a camera obscura , which gives inverted (but relationally accurate) images. But, of course, there is an obvious objection to this: if everything is upside down what’s the right way up? Then he has another model where he says ideas are products of interests and the ruling ideas are the ideas of the ruling class. This chimes with a lot of other ways of thinking about ideas in society which are not just Marxist. But then why is it that some people have the ability to propagate ideas that are in their own interest and other people don’t? Marx says in the German Ideology that that is because the ruling class are in control of the means of production of ideas, but then why is it that people who are oppressed lose the capacity to form ideas in their own interests and obediently take their ideas from ruling agencies?

3:16: So why do people believe things against their own interest?

MR: Different reasons, but the main one, surely, is that they make the world seem intelligible – not necessarily attractive, but intelligible. People need a meaning, as Nietzsche famously noticed. If your meaning is, for instance, that a nation that was once great has been dragged down by people who are parasitic and who are not authentic members of the national community, that will give a meaning to and legitimate inhumane and inegalitarian policies, even though, from the outside, it may seem that those who support those policies have more to lose than to gain from them.

3:16: Your new book is a revisionist reading of Kant. You’re arguing that Kant is religious and that you’re not understanding Kant if you miss that. Many contemporary Kantian interpreters – O’Neill, Korsgaard, Wood, and in the recent past Williams, Anscombe, Murdoch etc - would disagree wouldn’t they?

MR: After I’d finished writing the book I re-read something by John Rawls that I’d forgotten. It must have been one of the last things that he wrote, an appreciation of his late friend, Burton Dreben. In the piece he writes about his views about the history of philosophy and admits that he thought he never managed to get Kant right. Rawls says that he couldn’t grasp Kant’s ideas on freedom of the will and rational religion, obviously important as they were to Kant. I’d like to think that might have left him open to my way of looking at Kant. Rawls came to Kant having himself once been a deeply religious thinker, as we now know from the senior thesis that he wrote at. Princeton. But he came back from the war as a kind of utilitarian. It was in the course of defending utilitarianism against some of the more obvious objections to it that he came to an increasing sympathy for Kant. So Rawls approached Kant from a rather particular point of view. He looks at the Categorical Imperative as a kind of algorithmic procedure (he calls it, very inelegantly, the “CI procedure”) that will enable us to resolve the problems posed by apparent moral diversity. His students took this up in various ways.

Onora O’Neill, who was, I think, one of Rawls’s first doctoral students to work on Kant, explains this very clearly at the beginning of her terrific book, Acting on Principle . She came to Kant, she says, after an engagement with utilitarianism and, even though she now disagreed with much of utilitarianism, she continued to think that a moral theory that didn’t act as a guide to action is pointless. That idea of acting on principle where we look for a rational procedure for ethical decision-making in Kant goes together with the thought that such a procedure can’t be dependent on particular doctrines about God or any particular doctrines of metaphysical freedom. My reading of Kant is pretty much the opposite of that.

3:16: You think you need to put God and metaphysical freedom back in?

MR: Yes, exactly. I think that Kant is deeply concerned with freedom and that he has to be, given how important the idea of divine justice is for him. The freedom that’s going to make it just for you to be rewarded or punished by an omnipotent and judging deity at a Last Judgement can’t be just the self-understanding you have of yourself as an independent moral agent. If your freedom is defeasible in the light of a set of further facts that you and I have no access to but God does, then a God that’s going to condemn you for things that you did as a result of those things whose causal explanation you didn’t know about is an unjust one. That idea of divine justice is fundamental to Kant in my view, as is the idea that to be free is to be subject to a self-given law. It seems as if, if you’ve “given” yourself a law then, presumably, you can take it back. So a lot turns on this preoccupation with self-givenness. If it means some choice, act of will (“ Willkür ”, as Kant calls it) then, if you still have the power of will, you can un-choose it.

3:16: So why isn’t that a key problem?

MR: Well, self-givenness doesn’t mean that. It means that it hasn’t come to you from outside. To take a later formulation – from Schelling, but wholly in Kant’s spirit – it’s got to be a kind of internal necessity. To understand that, the person we need to go back to, oddly enough, is Spinoza. Spinoza in a letter which I quote in the book says: you know, there are two ideas of freedom. There’s the freedom of choosing in some undetermined way – free decision. But there’s no such freedom. Then there’s the freedom of being fully determined by nothing from the outside – free necessity – and that is true freedom. For Spinoza, only God has that because only God is a true substance. The German Idealists thought that human beings could have that kind of freedom, though, so that we’re determined only by what is internal to us. Furthermore, Kant thinks you don’t need to be a moral philosopher to know what’s right and wrong. He’s a moral unanimist . This is central to my understanding of Kant. Certainly, it now seems very strange. Lots of admired people hold exactly the opposite view. Derek Parfit argues that we shouldn’t be too upset by the existence of moral disagreement because it’s all a historical hangover from the domination of religion over ethics. Once the fog of religion has been cleared we can get on with doing ethics scientifically and we can hope for convergence.

3:16: You think that gets things the wrong way round don’t you?

MR: I think it’s 180-degrees wrong – all the more surprising, given that Parfit’s first degree was in history! I think that the idea that people disagree fundamentally about morality is actually a very modern one in the West. The great Western religions all believed that there was a core and kernel of “natural law”, the conscience of mankind as Saint Paul puts it, holding humanity together. Of course, people always thought that other people were wicked and that there was a huge amount of cultural diversity, but they didn’t believe, so far as I can see, that basic standards of morality were variable. And you find this in very odd places. You wouldn’t normally describe Hume as a believer in natural law. But Hume argues that apparent moral divergence is just people reacting reasonably to different circumstances. The underlying generative principles of morality are shared across societies.

3:16: What’s the link to the Lisbon earthquake and the question of evil?

MR: OK, let me back up. There are two ways in which you can read The Shadow of God . One way is you can read it from the inside out which is the way we’ve been talking about it till now. So we start from familiar interpretive topics – Kant on freedom, Kant on the categorical imperative, and so on – start from all those things that philosophers have always been very interested in in Kant, and then argue that the interpretive dead ends you come to lead you to take seriously things that modern philosophers try to steer their way around: transcendental freedom and the absolute value of the good will, for example. As you zoom out in this way you see that Kant is very concerned with the goodness of the world and the goodness of the world doesn’t consist in the world being made for human happiness – which is where the Lisbon earthquake comes in. The goodness of the world consists in it being made for human freedom. And human freedom isn’t just good in itself but also connects with the possibility of justice, that a world can exist in which there’s a balance between what people get and what they deserve.

This world is a world where there’s an imbalance between what people get and what they deserve and that leads Kant in two directions. First it leads him to the thought that we’re engaged collectively in a project to achieve justice in this world and that’s very important because it’s a theological perspective that doesn’t involve the miraculous. It’s very remote and Kant understands that we’re never going to get there but we’re working in that direction as an ideal. We don’t have to think that the natural facts of human beings’ existence are going to change or indeed that the natural facts about the world are, so that lions no longer eat lambs and so on. Justice can exist as a project in a world without miraculous intervention.

3:16: In that sense it’s realist.

MR: Yes. To step sideways for a moment: one of the things that separates Jürgen Habermas from his predecessors in the Frankfurt School is that, however much Habermas liked and admired Adorno, he thought his ideals were unrealizable absent what Habermas calls “the resurrection of nature”. So Habermas sees his predecessors as, basically, negative theologians, whereas he himself sees the realization of reason and justice as something that can be achieved within the constraints of the laws of nature as we know them. That puts him in agreement with Kant as a realist in the sense you mean. But then there’s the other bit which is Kant and the Last Judgement. The scary thought is that, according to Kant in his writings on theodicy, what should really trouble us is not good people having bad things happen to them. Good people are not entitled to have good things happen to them. It would be nice if they did, but that’s not a requirement of justice. The requirement of justice is that bad people be punished.

3:16: This is a sinister side to Kant isn’t it?

MR: Well, “sinister” may be a bit strong, but it certainly challenges those modern interpreters who enlist Kant in Team Liberal Humanism! It’s not confined to Kant, by the way. Reading Boyd Hilton’s book The Age of Atonement opened my eyes because he describes a very similar punitive retributivism in Victorian Britain. Hilton argues that it comes there from an amalgamation of Malthus and Bishop Butler. Butler has this view that, if we’re going to imitate and analogize heaven on earth it’s not going to be as a Land of Cockayne where there is ease and abundance, it will be within a culture where abstinence is rewarded and fecklessness is punished. Butler, by the way, was edited by none other than William Gladstone (how on earth did he find the time?) who is himself a model of that kind of Victorian religious ethos.

3:16: What would be a top down way of reading the book?

MR: From that perspective we start with the general project of reconciliation – “theodicy” in a broad sense – and show how it led to a form of theodicy in the narrower sense, and how the German Idealists pushed to its limit the idea of bringing together reason and religion. So Kant was not a secular thinker but he ended up being a secularizing one. At the same time, Kant moves out of the centre a little bit because the idea of historical immortality didn’t just spring up from German Idealism. It wouldn’t be thinkable in Fichte and Hegel without Kant. Likewise, Hegel is an essential source for Marx. So those immensely important modern ideas about historical self-transcendence, nationalism and revolutionary socialism, can be traced back in at least one or two removes to Kant. But then, as I try and establish in the last chapter, you have independent ideas about historical immortality emerging at the same time, especially in Diderot and the French Revolutionaries. And also some whom it might be surprising to find adhere to the idea. There are few people less Kantian than John Stuart Mill but the idea of historical immortality is important to him and he defends it in his essays on religion.

3:16: You say this is a Socratic approach, in contrast to Dionysian and Apollonian alternatives. So how does Nietzsche fit into this?

MR: I should say that this is not a book that aims to give a full-scale interpretation of Nietzsche: I’m just using some of his ideas as a schema. I’m following Nietzsche in order to steer a path between the celebratory Steven-Pinker-ish narratives of the development of Enlightenment rationalism and narratives of it as the triumph of instrumental reason at the price of the loss of experiential plenitude and social integration. I do have other precursors for my picture. It’s not too far from Weber or from the Adorno-Horkheimer dialectic of the Enlightenment, although it’s significantly different from both. And people who have read other work by me will know that nearly everything I’ve written has got something of Hans Blumenberg in it. Blumenberg’s idea that monotheism faces the threat of Gnosticism and tends to fall back into dualism when it faces the problem of evil is something that is clearly running through the book. What I’ve tried to show, though, is that Kant does not fall back into Gnosticism, although, in avoiding it, he ends up with a very different conception of divine goodness than Christianity (and Judaism) started from.

3:16: There is also something lost with Kantian rational religion?

MR: Yes. Iris Murdoch completely misreads Kant when she depicts “Kantian man” as Milton’s Lucifer. He’s not that at all. Was there ever a less Kantian sentence than “Evil be thou my good”? But she’s not wrong to think that there’s a kind of loneliness in Kant. If your vision of religion is that, although we may not understand, God has his purposes and we should trust them, that there’s a paternal benevolent source and presence upon whom we can rely even when our own resources give out, you’re not going to get that from Kant. Some people for whom I have the highest respect think something like it is an essential ingredient in religion. Charles Taylor, for instance, is by no means an anti-rationalist. But what’s wrong with the Enlightenment, for him, is the way in which it flattens reality to a point by which it can be fully grasped: the “immanent frame”, as he calls it. Kant is fully on board for us having a sense of reverence for the way the world goes beyond our comprehension, but he refuses to think that God can be a manipulator –even a benevolent manipulator – of human beings who conceals his purposes.

The idea that there’s a foreground and a background to human understanding and that God can be understood as part of the background is all right if it’s a source of awe and wonder but absolutely not if it is supposed to be a source of moral authority. If God is just then goodness must be something that is available to all of us. It can’t be a matter of divine grace which is given to some and denied to others. It’s interesting that there has been a huge emphasis on the personal quality of the relationship between the believer and the deity in modern religion. You find it, obviously enough, in Buber (the “ Ich ” and the “ Du ”) and in Levinas, but you find it too, I think (though I’m open to correction) in Christian personalism: the idea that we relate to God – the three parts of God – not as an equal person – that would be heretical – but as a person nevertheless. So modern Catholicism, despite its adherence to natural law, has not become a religion of impersonal pure logos . On the contrary, the Trinity is the embodiment of the family relationship: what is more personal than that? That is something you don’t and can’t get from Kant. Kant’s religion is not just chilly because of its emphasis on retributive punishment, but because there is no place for the personal warmth that people want from religion – Geborgenheit , as Edith Stein called it. Kant’s religion is too heartless to be the “heart of a heartless world”.

3:16: So where do we end up?

MR: If we no longer believe in a Last Judgement by an all-powerful creator and have transferred our redemptive hopes to some kind of trans historical community, a nation, humanity as a whole or even (gulp) a race, then what if we start to lose faith in the possibility of history as acting as this redemptive telos? That, in a way, was my starting point. The book is written forwards but it could have been written backwards from my puzzlement at Adorno’s very strange claim about Auschwitz: that Auschwitz was the modern equivalent of the Lisbon Earthquake.

3:16: What makes it so strange?

MR: Very briefly, this. Auschwitz was a horrific example of human evil but the Lisbon earthquake was troubling to believers just because it was not human evil. It was an act of God (or an act of nature). So why should we worry about human evil? ‘If plagues or earthquake break not heaven’s design/Why then a Borgia or a Cataline?’, as Pope writes. Although Adolf Hitler was far worse than even a Borgia or Cataline, the same principle surely applies. So here’s my interpretation. If you no longer look towards a divine creator and the Last Judgement but transfer your redemptive hopes instead to history, then something as horrifyingly contrary to anything that looks like a redemptive progressive narrative of history will undermine that alternative to the traditional narrative. Habermasians argue that we should understand the Nazi period as an interruption of progress, but, if I read him right, Adorno is saying it’s more than just an interruption, Auschwitz destroys our confidence that humanity is progressing – which then invites the question that I hope you’re going to ask me: doesn’t that mean you’re left being very pessimistic?

3:16: Exactly. So what do you say?

MR: Well, obviously Adorno himself is no model for evading that pessimism. But alongside his well-known cries of despair you can also find in Adorno (and I agree with him) a sense that, just because you can’t see time and history as guaranteeing that things are moving in the right direction, either because of the progress of the World-Spirit or because of the development of productive forces, we shouldn’t lose faith in our values. And those values are, in Adorno’s case and mine too, fairly standard, egalitarian, pluralistic ones: all human beings matter; suffering is always bad; toleration and acceptance of difference are good.

3:16: Doesn’t that mean then that those values are indestructible?

MR: Well, not because they exist in an eternal realm outside time and history. There are no guarantees beyond the individuals that have to sustain them. But yes, you’re right. There’s no real argument against a scepticism about values except to point out that most of the arguments for scepticism are inverted forms of very strong commitments to realism. If you’re looking for your morals to have the strong factual underpinnings that mathematics and the natural science have and they turn out not to have them then you may be left in a position of scepticism. But if you don’t think that that’s what’s required – if we make our commitments into just that, commitments – then maybe we’re OK.

3:16: It’s like the ending of the Lars Von Trier film Melancholia where the woman facing the earth’s destruction and certain extinction of everything living there continues to play with her child in full knowledge of the fact.

MR: Even if I didn’t believe in progress I would still feel very distressed by the thought of human extinction. In the last chapter of the book I start with a debate between Diderot and his friend the sculptor, Falconet, about the importance of the future. What would happen if we knew that a thousand years in the future a comet would wipe out mankind, Falconet asks? Falconet takes a radically Epicurean view and says that it wouldn’t matter, but Diderot thinks that it would mean an enormous loss of value even now: that people would not bother with anything like works of art and would just “grow cabbages”. I am with Diderot. I think knowledge of the extinction of humanity in a thousand years time would be an utter catastrophe and would destroy my sense of the world and my place in it.

3:16: Where does Schleiermacher fit in to your book?

MR: Well, his name means “veil maker” – hence Nietzsche’s joke that all German philosophers are Schleiermachers. But personally I think he’s an amazing thinker and writer. I think we can see Schleiermacher as the founder of a turn in religion that is frequently (but falsely) attributed to Kant. It’s a criticism of the way in which we construct narratives of the history of “philosophy” that Schleiermacher is left out, but he’s right at the centre of modern theology and he even appears in narratives about literature. The lines between the three in his day were nothing like they are now. Roger Scruton quotes Kant as saying he had found it necessary to “attack the claims of reason to make room for those of faith”. But that is exactly not what Kant says. (If he had I couldn’t have written my book!) Kant in fact says he has limited knowledge to make room for faith. Hence there is a huge space for rational religion without the claim of knowledge.

Schleiermacher, by contrast, does think that religion is beyond and outside reason. So what do we get? We get a very recognizably modern sort of religion which is all about our experience of the divine. It’s not about defending God’s goodness or justifying the world as being the product of an omniscient omnipotent benevolent creator. It’s about opening ourselves to the divine. I think that Schleiermacher is a kind of pantheist – the secret religion of the Germans as Heine said – or not so secret really! His idea is that, if only you focus yourself on the epiphanies that come from religious experience, these other matters will fade in significance. Although Schleiermacher remained a Christian minister, he didn’t think it was only through Christianity that people are brought to experience of the divine. So he also opened the way to much modern ecumenical religion. It’s not uncontested, of course – Karl Barth, the most celebrated Protestant theologian of the twentieth century, described the nineteenth century as “Schleiermacher’s century” but he wanted to push back against it. He wrote his “Church Dogmatics” to oppose the Schleiermacherian idea that all you need for religion is religious experience.

3:16: This resonates with a lot of contemporary pop thinking I bump into.

MR: Ah, I’m guessing you mean the sort of thing you find in Blake (“the doors of perception”) and Swedenborg and the idea that we are cut off from reality by a veil of illusion. Swedenborg thought that Heaven isn’t to be found in an afterlife but from us opening ourselves up to a noumenal reality which is veiled by the world of appearance. And, on one view, Kant is the antipode of this: he wrote his book Dreams of a Spirit-Seer against Swedenborg. On the other hand, it’s possible to see Kant as a sceptical Swedenborgian: that’s to say, someone who does believe a noumenal realm exists but doesn’t believe that experience of the noumenal realm is open to us. For Kant, unlike more sanguine types like Huxley or Blake or Emerson or Baudelaire, there’s no way we can open the doors of perception and let true reality flood in, either by praying a lot or getting stoned.

3:16: The avant-garde tradition is much influenced by this.

MR: Of course, the idea that we are living in a world where we are systematically deluded goes all the way back to Plato and the cave and St Paul looking through his glass darkly but it takes on a modern inflection with this Swedenborgian-Blakean reconfiguration of Kantianism. The “doors of perception” idea is a distinctively modern sort of mysticism. It leads naturally to standpoint epistemology and the thought that we need to tear the veil away from the illusions of the modern world and capitalism to unmask it.

3:16: This has all been very interesting but we need to bring things to a close, and, at this stage, I ask my guests to name five books.

MR: Only five! Seriously, it wouldn’t be helpful or interesting, would it, to say that people should read The Critique of Pure Reason , A Theory of Justice or Das Kapital – even though, of course, I think that they are surpassingly great and would certainly encourage everyone to study them? So here are five books that have been important to me for a very long time but that some of your readers may not know already.

M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp . This book was already a classic when I discovered it as a graduate student. I was pointed towards it by two beloved friends who were historians of German and English literature and that is another reason that I love it. Abrams attended a seminar that I did too when he visited Oxford in the mid-70s. At the end of one meeting he came up to me and said “I agreed with that question you asked”. I was too thrilled and star-struck to say anything back!

Hans Blumenberg, Paradigms for a Metaphorology . Blumenberg is another author who’s been a hero for me since my student days – not just for the staggering scope of his learning but also because of the way he tries to give a comprehensive account of the history of Western thought. I don’t follow him in all details, but Blumenberg’s underlying idea that monotheistic religions face a standing problem in trying to integrate (apparent) evil with the goodness of a creator-god runs through The Shadow of God as well.

E.R. Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational .

Perhaps the idea that we should study the Greeks because they embody the ideal of a life lived according to reason no longer holds sway in the way that it once did. But no one did more than Dodds to promote the Nietzschean idea that, in fact, Greek rationalism only makes sense when we see it against the background of what was otherwise a very non-rationalist society.

Frank Manuel, The Eighteenth Century Confronts the Gods . I first read Manuel because I was interested in the pre-history of the idea of “fetishism”. I soon realized that there is much, much more to it. It is one of the great books on the Enlightenment: nuanced, learned and highly original.

Philip Rieff, Freud: the Mind of the Moralist . It’s been claimed that this book was largely written by Susan Sontag (who was married to Rieff at the time) and I can believe that. It’s wonderfully well written and far better than anything else I’ve read by Rieff. At any rate, if, like me, you are still making up your mind about Freud, this is a great resource.

3:16: Those are all books by men who are no longer alive. Isn’t there anything today that excites you?

MR: Oh yes. I can see that that kind of sweeping but breathtakingly learned intellectual history for which I’m such a sucker is out of fashion – perhaps it isn’t really possible any more, given the pressures of modern academic life. But here are five books by living authors that I admire deeply.

Elizabeth Anderson, The Imperative of Integration . Anderson, as everyone knows, has been perhaps the most insistent critic of the ideal-theory-first approach of Rawlsian liberal egalitarianism. I think that this is her masterpiece: a brilliant illustration of how she thinks you should do political theory instead.

Joseph Fishkin, Bottlenecks . The sub-title of the book is “a new theory of equality of opportunity”. I think that almost undersells the originality and importance of this book. Once you’ve read Fishkin you start to see that looking at equality through the familiar contrast between “equality of opportunity” and “equality of outcome” (or, indeed, <em>pace</em>Elizabeth Anderson, “relational equality”) misses a lot of what entrenches social inequality in contemporary society.

Tae-Yeoun Keum, Plato and the Mythic Tradition in Political Thought . This is an amazingly ambitious first book. Keum starts from a reading of Plato that embeds him within the side of Greek culture that Dodds was concerned with, which she then extends to argue that Plato’s importance for Western political thought came as much from that as from his supposed embodiment of the ideal of rationalism.

Justin Smith, Divine Machines: Leibniz and the Sciences of Life . Leibniz is too difficult for me, but I admired this book enormously for the way that it shows how far Leibniz struggled with the problems – ontological and epistemological – that biology posed for early modern philosophy. Smith is using that to help chart the sources of Western thinking about biological race. It’s a fascinating and obviously important project.

Bernardo Zacka, When the State Meets the Street . On the back cover David Owen says that this book “reads as one might imagine a collaboration between Bernard Williams, Richard Sennett, and James Scott could turn out”. What more can one say?

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

Josef Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised

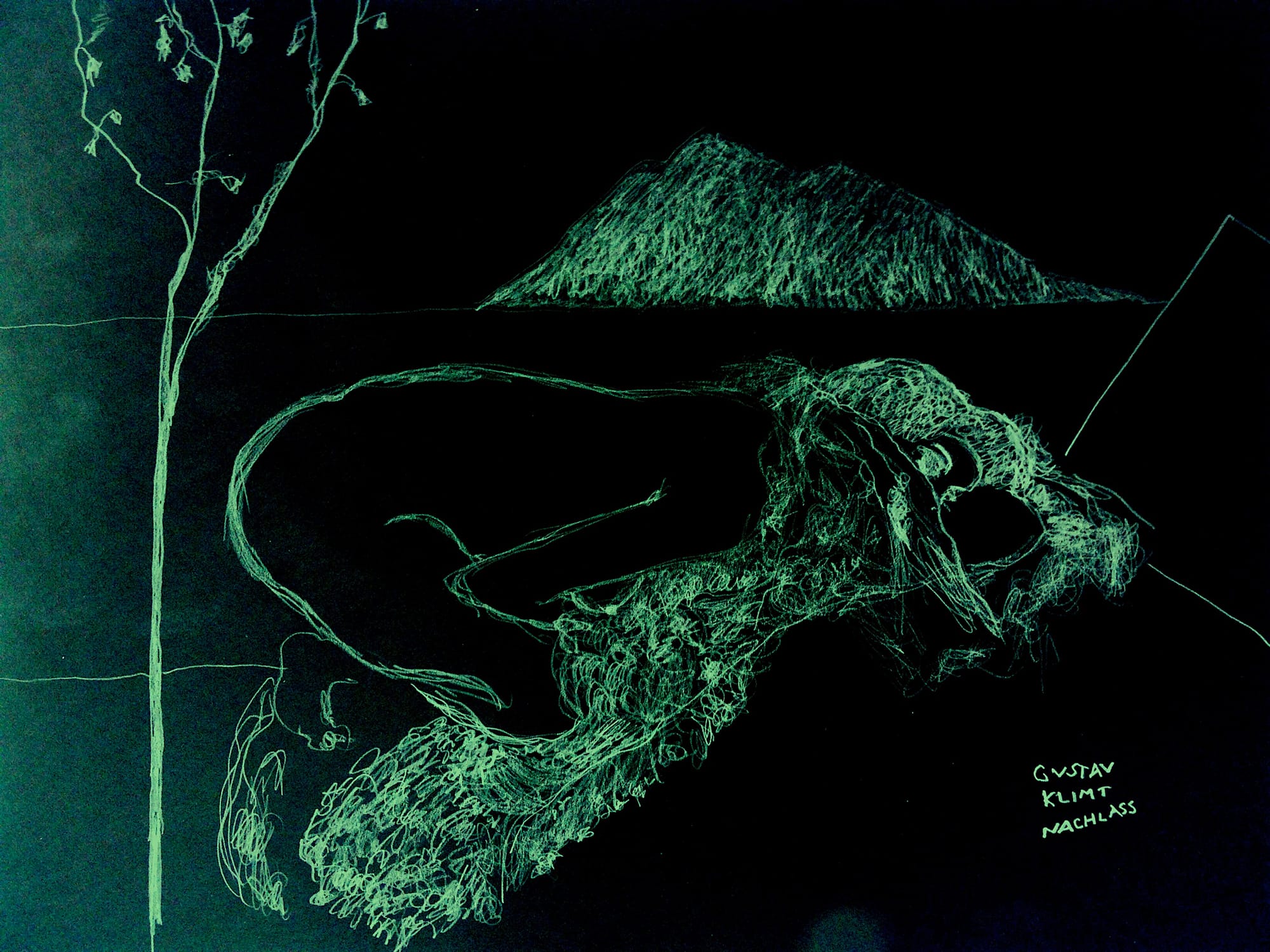

NEW: Art from 3:16am Exhibition - details here