Reasons For a Liberalism Without Perfection

Interview by Richard Marshall.

'Political liberalism offers a different, more inclusive, picture of liberal politics. On this view, liberal rights and institutions are not instruments to promote a particular way of life—they are rather meant to provide a fair framework within which each person can develop and pursue their own plan of life. You don’t need to hold a liberal view about how one ought to live to endorse this picture of politics—it’s meant to be a picture of our political life that can be freely endorsed by people with a wide variety of different doctrines.'On the more modest view that I prefer, pluralism is not an external constraint on liberalism, it’s rather a fact about liberal societies in particular. It’s a fact that in societies where basic rights and liberties are protected, there will always be the kind of reasonable disagreement that I described in one of my previous answers.'

'I argue that reasonable disagreements about justice are, by definition, justificatory and not foundational. This is because reasonable people are defined as those who share a normative ideal of society as a fair system of social cooperation over time between free and equal citizens. Their disagreements about justice necessarily occur within this shared normative framework. But reasonable disagreements about the good life aren’t necessarily like this.

'On my view there is no protected claim right, for example, for Neo-Nazis to march in the streets claiming that other citizens lack equal standing. The aim of such activities is fundamentally at odds with a fair system of cooperation amongst free and equal persons, and so there’s no protected right to engage in these activities any more than there could be a protected claim right to steal other people’s justly held property on the grounds that their interests are of no moral relevance.'

Jonathan Quong is interested in political liberalism, public reason, democracy, distributive justice, and the morality of defensive harm. He is an associate editor for Philosophy & Public Affairs, an associate editor for Ethics, and an area editor for Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. Here he discusses political liberalism, ‘liberal perfectionism’, objections to liberal perfectionism, Joseph Raz, whether liberal perfectionism is paternalistic and why that's a problem, political legitimacy, the puzzle that political liberalism should be aiming to solve and why it's more modest than often supposed, the importance of pluralism, why the internal view is better than the external view, general assumptions regarding justice in a liberal society, the scope and structure of public reason, and unreasonable people.

3:16: Let's begin by interrogating the various visions of liberalism currently in play. You start by giving a picture of the dilemma facing modern democratic states and their commitment to pluralism and disagreement. Can you sketch for us the two general claims - one about the nature of liberal philosophy and one about the nature of legitimate liberal states that underpin your philosophical position, (which is Rawlsian isn’t it, a form of his political liberalism?) and before looking at your position regarding liberalism can you say something about its liberal rival, a position you call ‘liberal perfectionism’? What are its main characteristics and why did you think it desirable to critique liberal perfectionism as you do in your book? Was it because you felt it was a position that had been given a relatively easy ride compared to political liberalism?

Jonathan Quong: Yes, that was one reason. Since Rawls and Charles Larmore first articulated different versions of the view, political liberalism has received an enormous amount of critical scrutiny, but liberal perfectionism, for whatever reason, hasn’t received the same kind of critical scrutiny.

But I focus on liberal perfectionism not just to try and redress this imbalance in literature. I also focus on it because I think it’s an obviously attractive and serious philosophical view—the most plausible alternative—and so it is important to try and figure out where I think it goes wrong.

3:16: Why is this argument between political liberalism and liberal perfectionism such a crucial debate?

JQ: First, there’s an obvious practical upshot. Many current laws and public policies (e.g. laws regulating sex work, recreational drug use, marriage, abortion, antidiscrimination exemptions) are sometimes justified by appeal to controversial claims about the good life or controversial religious or ethical ideas over which there is reasonable disagreement. Whether these laws can be legitimately justified in this way depends on whether political liberalism or liberal perfectionism is the correct position.

Second, the debate also bears on how we understand the liberal project and who can be a full participant in that project. Comprehensive perfectionists argue that liberalism is ultimately grounded in a substantive conception of what constitutes a good life. Many, for example, argue that this view of the good life centers on an ideal of personal autonomy; of being the author, or at least part author, of the central decisions in your own life. On this view, liberal politics is a vehicle by which we help people realize a particular conception of the good life. I think this is, in the end, a problematic way to conceptualize the liberal project. On this view, liberalism is on a par with any competing theory of the good life, and liberal politics is, in one way, no different than the politics of those who seek to use the power of the state to promote Catholicism, or Islam.

Political liberalism offers a different, more inclusive, picture of liberal politics. On this view, liberal rights and institutions are not instruments to promote a particular way of life—they are rather meant to provide a fair framework within which each person can develop and pursue their own plan of life. You don’t need to hold a liberal view about how one ought to live to endorse this picture of politics—it’s meant to be a picture of our political life that can be freely endorsed by people with a wide variety of different doctrines.

3:16: So what are the main objections to liberal perfectionism as you see them? Joseph Raz is perhaps the best known defender of this view with his argument from autonomy. What’s his argument and why is it flawed? Is autonomy no longer justifiable or important to the liberal?

JQ: Raz’s political theory is rich and complex, so I won’t be able to do it justice here. Personal autonomy involves being the author or at least part author of your own life; shaping your life through a succession of free choices under the right conditions. For Raz this is a central part of what’s involved in leading a good life, at least under modern conditions. He also holds the view that it is the goal of all political action to enable individuals to pursue valid conceptions of the good. These two premises entail that political rules and institutions should aim at helping people lead autonomous lives. There are three main conditions needed to live an autonomous life. First, you need the mental abilities to help you understand and navigate the choices you face. Second, you need to have an adequate range of sufficiently diverse options from which to choose. Third, you need to be sufficiently independent from the will of others—this entails being sufficiently free from coercion and manipulation. One other thing that’s important to understanding Raz’s picture is that choices aren’t valuable merely in virtue of having been selected autonomously. Autonomy is only valuable when it’s directed at the good.

This picture provides the justification for Raz’s perfectionism and also his liberalism. It supports perfectionism since the state should promote activities and ways of life that are valuable. But the importance of autonomy means that the state should not coerce or manipulate people into pursuing valid conceptions of the good. So the view remains liberal. To promote autonomy we need liberal rights and institutions that protect people’s independence. Liberal rights and institutions will also tend to protect a diverse range of lifestyles and options, thus contributing to one of the necessary conditions for autonomy. But within the framework of those liberal rights and institutions, the state can and should promote valuable conceptions of the good and discourage people from pursuing disvaluable conceptions, for example, via subsidies and taxes.

Although appealing in lots of ways, I’ve come to the conclusion that this picture of political morality suffers from serious problems. One problem is that Raz’s conception of autonomy cannot consistently ground a form of perfectionism that is liberal. Raz says autonomy is only valuable when directed toward good options. So why should someone with Raz’s commitments be opposed to coercively preventing people from making bad choices? Why shouldn’t the state threaten criminal sanctions to stop people from making objectively bad choices, such as watching Michael Bay movies? Raz’s answer is roughly as follows. Locking people up limits their freedom to pursue good options as well as bad ones. And we shouldn’t reduce people’s ability to autonomously choose the good merely in order to prevent them from choosing badly.

I have two main worries about this view. First, it makes our rights against interference with self-regarding activity contingent in a way that seems implausible. Suppose if the government developed the technology to prevent people from choosing bad activities in a way that involved no threat of criminal sanction—maybe we could be hypnotized to stop us from even contemplating bad options like Michael Bay movies. This would be a profoundly illiberal form of interference in citizens’ lives, but Raz’s argument doesn’t seem to preclude it.

Second, Raz emphasizes that coercion and manipulation both undermine independence and thus autonomy. But many perfectionist policies, such as subsidies for valuable activities, are manipulative. Thus, if autonomy is the basis for liberal rights that prohibit coercively interfering in people’s lives for the their own sake, consistency demands a similar prohibition on many perfectionist subsidies. So I think we end up with a dilemma. A consistent application of the value of autonomy either allows a lot less perfectionism than Raz assumes, or else it allows a lot more illiberal interference than has been assumed.

3:16: You say perfectionism is paternalistic – you see that as a problem but why? Couldn’t paternalism be benign? Why do you argue against it?

JQ: On my view, you act paternalistically toward someone when you attempt to benefit someone, but you do so, at least in part, because you form a negative judgment about that person’s ability to make a good decision if left to their own devices. When we treat others in this way we don’t treat them as having the ability (at least in a given context) to effectively pursue their own plan of life. I think it’s presumptively wrong to treat competent adults in this way—it’s inconsistent with our moral status as free and equal persons. But I’m not an absolutist about this: the presumption can be defeated if the reasons in a given case are sufficiently compelling. And I don’t think the presumption applies to younger children or people who have very serious mental disabilities, since it’s uncontroversial that such people do lack the effective ability to pursue their own plan of life. Paternalism in those cases can be perfectly appropriate and necessary.

Part of liberal perfectionism’s appeal is supposed to be that it isn’t paternalistic in the way that illiberal forms of perfectionism can be. Liberal perfectionists don’t, for example, want to use the power of the state to coerce people into making particular choices about their own lives. But I argue that it still entails a lot of paternalism because acts don’t have to be coercive to be paternalistic. For example, liberal perfectionists often argue that the state should subsidize valuable activities or ways of life. But why assume the state needs to do this? Why won’t citizens pursue good options so long as they are each provided with their fair share of rights and resources? I suggest that it’s often going to be hard for perfectionists to answer this question in a way that avoids the paternalistic motive.

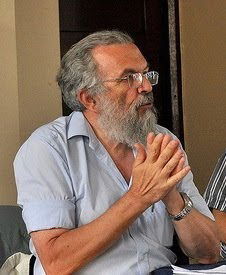

[Joseph Raz]

3:16: How do you see political perfectionism’s approach to political legitimacy? Is it a failure?

JQ: Raz offers the most influential account of political legitimacy in the perfectionist family. A central part of his conception is the normal justification thesis: “the normal way to establish that a person has authority over another person involves showing that the alleged subject is likely better to comply with reasons which apply to him . . . if he accepts the directives of the alleged authority as authoritatively binding and tries to follow them, rather than by trying to follow the reasons which apply to him directly”.

This is an appealing idea. For example, suppose several bystanders witness a bad accident. There are several victims with serious injuries but it will be a while before the paramedics arrive. Fortunately, one of the bystanders is a doctor and she knows what to do—she begins issuing commands to the other bystanders about what needs to be done to save the victims. I think, within limits, the doctor becomes a practical authority with regard to the other bystanders: they have a duty to do what she says because this is the best way for each to help save the victims.

Where the normal justification thesis goes wrong, I think, is that it’s too expansive; it refers to all reasons for action, including reasons that don’t have anything to do with our obligations to others. Maybe what you have most prudential reason to do is to stop watching re-runs of your favorite sitcom, and learn to play chess instead. Maybe you’d be more likely to make this kind of correct decision if you took your Aunt’s directives as authoritative rather than trying to work things out for yourself. But it doesn’t follow that your Aunt has practical authority over you with regard to such decisions. The reasons have nothing to do with her or anyone else. Raz is aware of this kind of worry. He claims that because we often have reasons to make personal decisions autonomously, it won’t be the case that you can really best comply with the reasons that apply to you by following the directives of others in cases involving personal decisions. I don’t find this persuasive. There will be plenty of cases where it’s more important that we make the correct decision even if we don’t do so autonomously, but it still doesn’t follow that others can gain authority over our self-regarding decisions.

Instead I endorse a version of the natural duty view of political legitimacy. I propose we narrow the range of the normal justification thesis to duties of justice: One way to establish that a person has legitimate authority over another person involves showing that the alleged subject is likely better to fulfill the duties of justice he is under if he accepts the directives of the alleged authority as authoritatively binding and tries to follow them, rather than by trying to directly fulfill the duties he is under himself. This kind of view explains why the doctor in the example above can become an authority with regard to the bystanders: the bystanders have duties of justice to try and help the victims of the accident. But it doesn’t entail that others can become authorities with regard to your self-regarding decisions, since those decisions don’t involve duties of justice.

3:16: So what is the puzzle that political liberalism should be aiming to solve, and why do you think it’s rather more modest than might be supposed?

JQ: Some people conceive of political liberalism as a very ambitious project: they see the goal as being the justification of liberal rights and institutions despite the fact there is so much disagreement about basic moral, religious, and political ideas. On the Rawlsian view that I favor, the project is more modest. The aim is to try and understand the structure and limits of liberal politics in light of the fact that any free society is going to be characterized by the fact of reasonable pluralism or disagreement.

3:16: What’s the importance of pluralism in your approach – and how should we best characterize it so that we understand the liberal dilemma best? You don’t think pluralism a given in all worlds do you, but rather something that is particular to liberal societies? Is that right and how does this help us grasp the importance of pluralism for you in forming what you call an ‘internal’ theory of liberalism?

JQ: It’s helpful to continue with the contrast between the ambitious and modest interpretations of political liberalism. On the ambitious view, pluralism is a fact about the modern world which liberalism—like any other theory of political morality—must address. On this view, if liberalism (including its most foundational ideas) cannot be shown to be acceptable, in some sense, to the diverse constituencies of modern societies, then liberal rights and institutions lack legitimacy. I call this the external view, since pluralism is understood as an external constraint on the success of a liberal theory of politics. On the ambitious picture, political liberalism aspires to vindicate liberal norms and principles to a very diverse group of people.

On the more modest view that I prefer, pluralism is not an external constraint on liberalism, it’s rather a fact about liberal societies in particular. It’s a fact that in societies where basic rights and liberties are protected, there will always be the kind of reasonable disagreement that I described in one of my previous answers. The central question, on this view, is what form political reasoning and justification must take in a well-ordered liberal society, given such a society will unavoidably be characterized by reasonable disagreement? I call this more modest view the internal conception of political liberalism, since pluralism is a fact internal to liberal politics. On this view, the only people to whom laws and institutions need to be justified are the reasonable people who would inhabit a well-ordered liberal society. Those people would endorse certain moral premises: the idea that citizens are free and equal, and that society is supposed to be a fair system of social cooperation. So quite obviously, this is not a project that tries to justify liberalism itself—it assumes fairly liberal premises. The project is instead about trying to understand what kinds of political arguments and what kinds of policies are legitimate within a well-ordered liberal society.

3:16: What benefits does this internal theory have over its rivals?

JQ: I think the internal view has a number of advantages over the external view. To begin the external conception faces an obvious difficulty: if pluralism is a fact about the world that liberalism must accommodate, it seems as if the constituency of persons to whom liberal norms and principles must be justifiable will be all the real people who inhabit modern liberal societies. The problem is that real people sometimes hold repugnant moral views, and they might be blinded by self-interest or other biases. Why would we grant such people the authority to determine our fundamental political principles? The proponent of the external conception will have to admit that they aren’t interested in justifying norms to people exactly as they are—we must idealize the constituency of persons to whom we justify our principles and laws: perhaps we must assume they don’t hold certain obviously false moral views or more strongly perhaps we must assume they endorse certain moral ideas. But once this much is conceded, the distinction between the external and internal views begins to collapse—the proponent of the external view is admitting that we cannot strive to accommodate all the kinds of pluralism we find in real societies—we’re going to have to restrict the constituency in various idealizing ways. But this is exactly what the internal conception recommends. So one obvious advantage of the internal view is that it is clear about an unavoidable fact: the project of liberal justification has to begin from a particular moral point of view—some moral ideas are just presupposed. As Rawls says, “not everything, then, is constructed; we must have some material, as it were, from which to begin”.

Second, because the constituency of justification is so clearly idealized on the internal view, there is no worry that political liberalism will end up being hostage to the current political culture: there’s no risk that political liberalism generates a kind of political relativism. What matters instead is which norms and laws could be justified to the reasonable people who populated a well-ordered society. Those people are defined by reference to certain basic moral ideas, and so the content of liberal justice is not determined by reference to empirically contingent beliefs of real people, but rather by appeal to a philosophical ideal of citizens in a well-ordered society.

Finally, the internal conception is attractive because it reflects something important about the limits of liberal political philosophy, and in fact about moral and political philosophy more generally. There’s an understandable tendency to expect a normative framework to have some kind of external justification, that is, to expect a justification for the framework that doesn’t presuppose any of the normative ideas we find within the framework. Sometimes this is possible, but there are limits. For example, I don’t think there’s a sensible answer to the question “why be moral?” that doesn’t presuppose some moral notions. We can’t justify morality, for example, by appeal to non-moral standards such as self-interest. Similarly, I’m skeptical that it makes sense to think that we can or should try to justify some version of liberalism to those who reject some very basic liberal egalitarian ideas.

3:16: How does your approach cohere with perhaps given, general assumptions regarding justice in a liberal society? Are there any such assumptions? Don’t people disagree about justice just as much as they do about the good life?

JQ: People do of course disagree in deep and important ways about justice. I don’t deny that reasonable disagreement about justice is also an inevitable feature of a liberal society. To some this looks like a fatal problem for political liberalism. If there’s reasonable disagreement about justice and the good life, then why does political liberalism preclude controversial claims about the good life from playing a role in political justification, but not controversial claims about justice? Critics allege there’s no good justification for this asymmetrical treatment. I call this the asymmetry objection.

My response to the objection involves distinguishing two different forms of reasonable disagreement. On the one hand some disagreements are justificatory. These are disagreements where the participants share some standard of evaluation for assessing the claims over which they disagree. Two people who both accept Rawls’ main assumptions in constructing the original position, for example, might have a justificatory disagreement about whether parties in the original position would endorse the lexical priority of the basic liberties. On the other hand some disagreements are foundational. These disagreements go all the way down: the participants don’t share a framework for assessing their competing claims. When an atheist and a devout Catholic debate the (im)morality of pre-marital sex, their disagreement is likely foundational.

I argue that reasonable disagreements about justice are, by definition, justificatory and not foundational. This is because reasonable people are defined as those who share a normative ideal of society as a fair system of social cooperation over time between free and equal citizens. Their disagreements about justice necessarily occur within this shared normative framework. But reasonable disagreements about the good life aren’t necessarily like this. Reasonable disagreements about religion or the good life can be, and frequently will be, foundational. I argue that this makes a big difference when we think about the kinds of considerations that can be legitimately used to justify the exercise of political power. Reasonable people might disagree about justice, but at least their disagreements occur within a shared normative framework that they all accept, one that also significantly constrains the range of that disagreement.

3:16: What claims do you defend regarding the scope and structure of public reason?

JQ: The idea of public reason, which is part of political liberalism, requires that at least some exercises of political power be publicly justified, that is, be justified in a way that is acceptable to all reasonable persons. The scope of public reason concerns the range of issues to which this constraint applies. Rawls’s views about the scope of public reason are somewhat unclear, but in one passage he seems to suggest that it should apply to what he calls constitutional essentials and matters of basic justice, but that it needn’t apply to other forms of legislation.

I argue for a more expansive conception of public reason’s scope. I argue that the idea of public reason applies, in principle, to all exercises of political power, and I criticize three arguments that might be offered in favor of the more restrictive view. Part of the reason I favor the more expansive view, however, is that I’ve got a fairly restrictive view of the purposes for which political power ought to be exercised. In my view, the state’s function is to secure just conditions; to ensure that free and equal members of the community can interact with one another on fair terms. Given the fact of reasonable pluralism, fair terms will need to be ones that meet the test of public reason. Since claims about justice must meet the test of public reason, and since political power should be exercised to secure just conditions, I think the scope of public reason includes all exercises of political power.

3:16: And how would you respond to people who according to your theory are unreasonable? This seems like a key question today where many of your political liberal assumptions are disregarded or held in contempt by all sorts of groups?

JQ: Unreasonable people, as I define them, are those who reject at least one of the fundamental assumptions of the political liberal project. They reject the idea that society ought to be a fair system of social cooperation, or the idea that citizens are free and equal, or the fact of reasonable pluralism.

In asking how we ought to respond to such people, there are two main issues. One is whether such people need to be included in the constituency of public justification, that is, the constituency of persons to whom our political rules and institutions need to be justified in order to be legitimate. My answer to this question is no. As I indicated in answering a previous question, I don’t think we can or should seek to justify our basic liberal norms to those who reject some minimal liberal egalitarian ideas.

The second issue is whether unreasonable persons are entitled to the same package of liberal rights and freedoms as other citizens. Some have suggested that if the unreasonable are excluded from the constituency of public reason, this somehow entails that they are not entitled to the same rights and liberties as other citizens. I reject this view. Just because unreasonable citizens are not part of the constituency that determines the content of claims of justice, it doesn’t follow that they aren’t members of the political community with the same entitlements as others.

However, I do insist that there are no protected claim rights to act in ways that are unreasonable, that is, to act in ways that aim at the rejection of political liberalism’s normative ideal of fair cooperation between free and equal persons. On my view there is no protected claim right, for example, for Neo-Nazis to march in the streets claiming that other citizens lack equal standing. The aim of such activities is fundamentally at odds with a fair system of cooperation amongst free and equal persons, and so there’s no protected right to engage in these activities any more than there could be a protected claim right to steal other people’s justly held property on the grounds that their interests are of no moral relevance.

That said, even if there’s no protected claim right to engage in such acts, this doesn’t mean the state should necessarily intervene or use force to stop such activities. We should always be very wary of state exercises of power that target minorities’ speech or activities—there are powerful practical reasons to worry about such exercises of power. But these reasons to be worried about abuses of power are different, and require different normative judgments, than cases where we think people have protected rights against government interference. For these reasons I’m very sympathetic to the arguments that Jeff Howard has recently advanced in his excellent article, “Dangerous Speech”.

3:16: And for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

JQ:

John Rawls, Political Liberalism

Gerald Gaus, The Order of Public Reason

Judith Jarvis Thomson, The Realm of Rights

Jeff McMahan, Killing in War

G.A. Cohen, Rescuing Justice and Equality

The first two books by Rawls and Gaus are, in my view, the two most important contributions to the literature on political liberalism and public reason. The next two books, by Thomson and McMahan, have deeply influenced my thinking about moral rights and the morality of defensive force, which is the subject of my most recent book. And the last book, by Cohen, is on my list partly because Jerry Cohen was an early exemplar to me of what political philosophy could do, and also because, although I disagree with many of the claims in the book, I think it represents maybe the deepest and most powerful challenge to Rawls’s political philosophy.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes