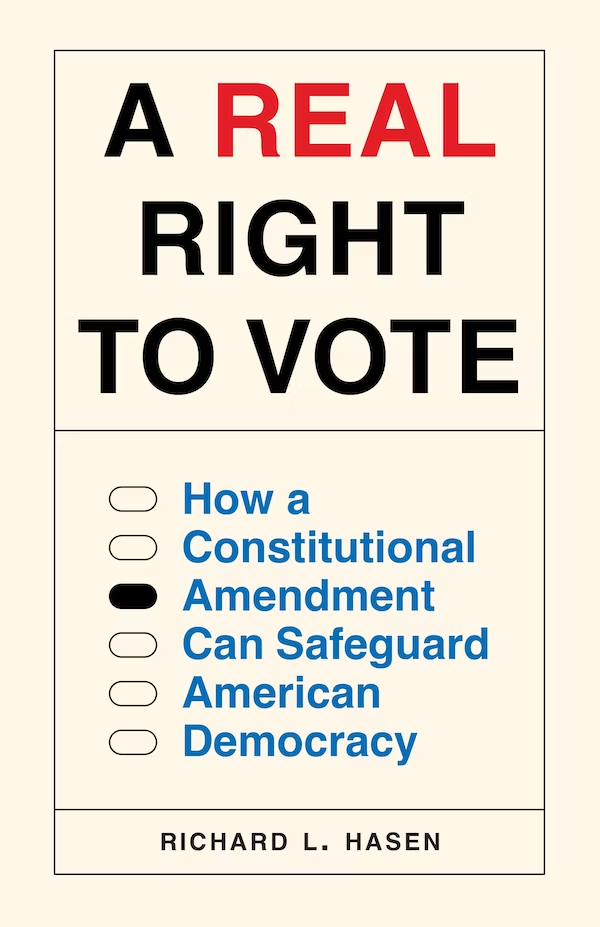

Richard L. Hasen, A Real Right to Vote: How a Constitutional Amendment Can Safeguard American Democracy

Richard L. Hasen, A Real Right to Vote: How a Constitutional Amendment Can Safeguard American Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2023)

I spent a good deal of space in my review of Rick Hasen’s previous book, Cheap Speech, marveling at the author’s prodigious industry. Rather than descend into that rabbit hole again, I will say here only that each new book, paper, op-ed, TV appearance, etc. may cause one to wonder if prior, ostensibly scientific claims regarding the absolute impossibility of perpetual motion machines ought to be reconsidered.

My sense of the earlier book was that, although it was an engaging read full of important truths, the warnings there itemized about democratic failings would probably have seemed obvious to most people likely to read that book, and the proposals for handling them were a bit anemic: mostly hopeful sketches of changes that might not have much effect even if they could be implemented. (I want to stress that that was no mortal sin, however, for NOBODY seems to have an abundance of good ideas for addressing intractable problems like the inexpensive dissemination of disinformation given the availability of AI.)

In any case, no such complaints can reasonably be lodged against A Real Right to Vote. Here, both the diagnoses and the recommended cure(s) are deep and carefully fleshed out, and both will be illuminating even to those who watch a lot of MSNBC or Fox News. It is immediately apparent that Hasen has thought long and hard about where we are going in the U.S. given a spate of recent Supreme Court rulings that are much less sympathetic to the rights of voters than they are to the power of states to do whatever happens to appeal to them at the moment in the area of voter qualifications and election administration. Hasen makes clear not only what needs to happen about this crisis, but what is politically feasible. (It is telling that, even since this book has gone to press, a U.S. Appeals Court decision–which may, of course, be reversed–has denied that anybody but the Attorney General of the United States may bring a suit under the Voting Rights Act. This, in spite of the fact that since that law’s passage in the 1960s numerous cases have been brought by individuals and groups, and no prior court has ever found that any such application for redress should have been simply thrown out on the extremely radical theory that only one ostensible voter in the world has ever had standing to sue.

Unlike a stream of current hodgepodge books (or arguably pointless theoretical tomes like my own), Hasen’s new work is entirely focused on advocacy for a single straightforward remedy--passage of a Constitutional Amendment (or several related Amendments). What has to happen, he argues, is that we must guarantee roughly equivalent voting rights to all adult citizens residing in the U.S.-- at least those who have not been convicted of a felony and are minimally competent. That is, no North Dakota may require Native Americans to have a conventional street address or to drive over 300 miles to cast a ballot.

I say that a group of related reforms is considered in the book because Hasen actually presents a smorgasbord of entrees of varying extent, so those with a taste for a more nutritional democracy–say, one that allows felons who have done their time to vote, or that promises a national popular vote for President, or that gives statehood to Puerto Rico or the District of Columbia, or that eliminates the two-Senators-per-state rule– can all have a look at what is needed. But he concentrates on the single provision that he takes to have the greatest chance of passage: an Amendment that makes it absolutely clear that everybody born in the U.S. or has otherwise gained citizenship here can easily cast a ballot or run for office. Those votes (except, of course, in U.S. Presidential or Senatorial elections) would be required not only to be roughly equivalent in weight to every other citizen’s vote, but roughly as easy to cast. That would mean that there could be no extra obstacles erected for those living on Native American reservations, or on military bases, or attending universities…or for indigent minorities without drivers’ licenses.

As Hasen patiently explains, the case law on these matters has swerved hard right since the halcyon Warren Court days, perhaps because Republican appointees to the Supreme Court have at least acted as if they have been fueled by the widespread view among GOP regulars that Native Americans, college students, recent immigrants, and poor urban Blacks are likely support Democrats or liberal causes–and that that cannot be good. As this anti-democratic turn has recently accelerated rather than slowed, it might be wondered how any Amendment along Hasen’s lines could have a chance of achieving the widespread support needed for ratification. But Hasen makes the case that Republicans are likely to be attracted to the anti-fraud provisions that he recommends be featured in any right-to-vote Amendment: the automatic generation of voter IDs and the creation of voter registries in every state. In his words, “Any state concerned with deterring fraud would be able to take great comfort in the identification requirement imposed by the amendment.” In his view, passage would clearly lower the amount of election-related litigation, a caseload which he notes has ballooned dramatically since the doleful days that the chads hung in Florida. Furthermore, understanding the federalist bent of those most likely to oppose his plan, Hasen takes the time to reassure his readers that none of the changes he seeks would require anything like a Beltway takeover of election administration from the states.

Important as addressing the voting obstacles placed in front of certain groups is, it seems not to be the main goal of Hasen’s proposed voting rights Amendment. Rather, the overriding target seems to be election subversion. Hasen’s detailed retelling of Donald Trump’s brazen and contemptuous attempt to steal the 2020 Presidential election is absolutely chilling. And he warns that, in spite of important improvements to the Electoral Count Act enacted since January 6th, the chance that any residue of democracy will entirely disappear in the U.S. is growing. It is in front of this depressing backdrop that he makes his compelling case that the way–perhaps the only way–to halt a U.S. descent into authoritarianism is a voting rights Amendment to its Constitution.

Hasen argues that what he prescribes “would confirm that within each state voters have the right to vote for president in an election; the choice would no longer be up to the state legislature….There would simply be no room for arguments…that state legislatures can usurp the powers of the voters or discriminate either against voters or among voters.” In addition, “an amendment would be a new tool for voters to assure protection from law enforcement for free and fair voting.” I believe many readers will join me in trusting that so careful a reviewer of the relevant case law as Hasen will have drafted his Amendment in precisely such a manner as is needed to address the main election subversion issues as well as those matters involving discrimination and unequal access to the vote. I, at any rate, take great comfort in Hasen’s legal acumen.

The add-on versions of the Amendment provided will be found quite beneficial, especially by those, like myself, who deny the U.S. had anything really deserving the name “democracy“ even prior to the recent SCOTUS decisions and Trumpian subversion activities. No doubt, one can agree that a return to secure selections of Electoral College members and Presidents, along with new safeguards of every citizen’s equal right to participate in our particular form of Madisonian crazy would be an improvement, but unless a voting procedure requires both majority rule and appropriate minority voice, it seems to me inappropriate to designate it a democracy in the first place. Hasen has a somewhat more conservative take on such matters, as he seems to believe that the main point of abolishing the Electoral College is not to institute self-government by majority, but that it would “do even more to thwart election subversion.” He writes, “It would be quite surprising to see as little as a one-million-vote margin between two candidates out of at least 150 million votes cast. Messing with how votes are tallied within states would have to be on a tremendous scale to have the chance of altering a presidential election result. That change, perhaps more than any other, would help secure the integrity of a presidential vote count.”

Well, yes. We surely do not want the Presidential vote count to be corrupted in anything like the manner that a handful of authoritarians planned for 2020. But those who have read my book on this subject will understand my hesitancy to advocate for the expenditure of the tremendous amount of effort necessary to ratify a Constitutional Amendment just to keep an extremely unreliable jalopy on the road. [FWIW, my book also goes into considerably more (and boring) detail on reasons and criteria for residency and competence requirements–and why even felons still in prison should not be denied a vote.] In any case, Hasen has made the expansive (i.e., better) versions available here, and again, one feels implicit trust in his ability to draft precisely what is necessary. I myself might think it would be better to shave down the original version a bit, give up on hopeless proposals to alter the two-member-per-state Senate (because a much better solution would be to simply abolish that branch completely), and insert the remaining suggested enhancements into a single Amendment that would turn the U.S. into something like an actual democracy, but I am hesitant to substitute my judgment for that of so acute an attorney and political scientist as Hasen.

Whichever version of the Amendment(s) one happens to prefer, I don’t think it can be sensibly doubted that this is an extremely important work that all who want to live under an authentic representative democracy should begin by reading, and continue by doing whatever they can to help turn Hasen’s proposal into one of the foundational laws of this land.

About the Author

Walter Horn is a philosopher of politics and epistemology.

His 3:16 interview is here.