Science Denial and Post-Truth: On Our New Dark Age

Interview by Richard Marshall

' If we were out on a fishing boat and you didn't want to put on your life jacket because you felt that "God would provide" that is your choice. But if there was a storm coming up and you wanted to break the radio because "we can count on God to rescue us" then you've put me at risk too. To me, an awful lot of science denial seems like the latter. If someone believes in Flat Earth, I guess they're not really hurting anyone but themselves (although they are contributing to a denialist culture, which does hurt others). But what about disbelief in climate change or the Covid-19 vaccine? There I think I am justified in being intolerant because someone's irrational and false beliefs are putting the rest of us at risk.'

'I offer the idea that what is really special about science is not its logic or method, but its attitude toward evidence. The scientific attitude is the idea that (1) scientists care about evidence and (2) they are willing to change their mind on the basis of new evidence. And that's it.'

'Seventy years of awesome success by those who wished to deny the truth about evolution, climate change, etc., did not go unnoticed by political operatives. One day they said "hey, if you can lie about scientific facts, you can lie about anything." Like maybe the outcome of an election? And yes, I think that one of the other roots is post-modernism, which is largely left-wing. Now they didn't intend it. They were playing around with the idea that there was no such thing as objective truth, and that perhaps this meant that anyone making an assertion of truth was merely making a power grab. That all sounds fine when you're in the university doing literary criticism, but at a certain point these ideas began to create the "science wars," where humanists began to attack the idea of scientific truth.'

'What I believe in is the doctrine of underdetermination. I believe that reality is consistent with many different descriptions of it, some of which offer good theories and some of which do not. But even among the ones that fit, there are many that might work. So how can we non-arbitrarily choose one and call that reality? That seems to me what the realists want to do. They are privileging the theories we now have over the ones we might have had, or might have in the future.'

'In the past, I've often referred to myself as a methodological naturalist, because I believe that the methods of natural and social science should be identical. But I think you're asking about a more stringent version of naturalism: the idea that all phenomena at the secondary level can be explained by phenomena at the primary level. Some people take that all the way through physicalism, which is an epistemological commitment that comes out of a very sparse ontology. And there are other proud reductionists out there. But I'm not one of them.'

'I am against any kind of ideological interference in scientific reasoning. To me, "dark age" thinking is emblematic of the type of mind that wants an answer -- that wants certainty at all costs -- and damn when the evidence tells you you're wrong. To me, that's the mark of an incurious mind.'

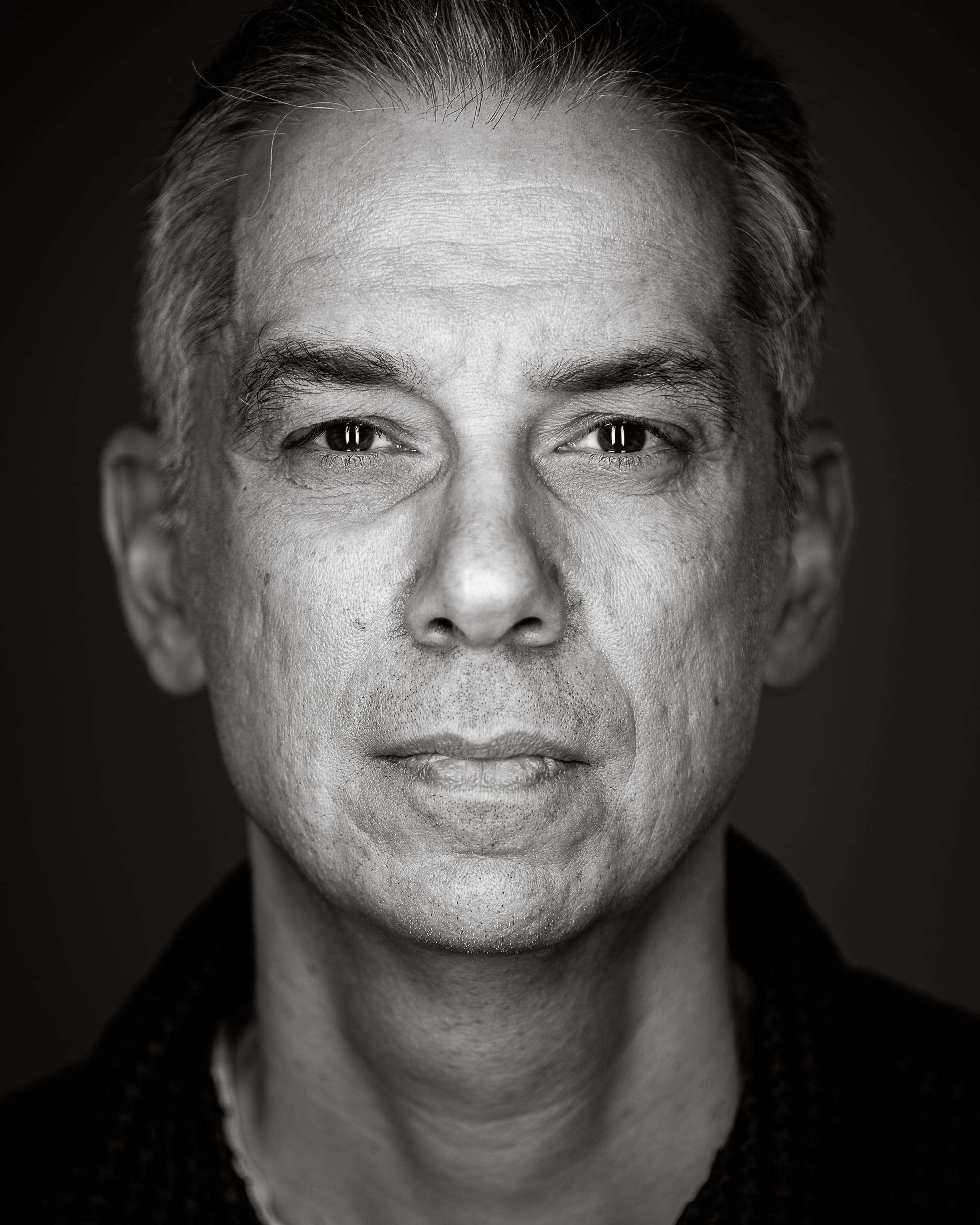

Lee McIntyre is interested in the philosophy of the social sciences, as well as attempts to undermine science and the appropriate response to these attempts to undermine scientists. here he discusses science denial, its dangers, what to do about it, why shouldn't it be tolerated, the demarcation question, whether social sciences are really sciences, why we should focus on the failures of science, post-truth, why philosophy of science is useful, do scientific laws exist, falling short of certainty, anti-realism, induction and Bayes, whether he's a mad dog naturalist, and finally why we're in the dark ages of human behaviour.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Lee McIntyre: There were a couple of factors, all stemming from my childhood. When I was young I loved to read the World Book Encyclopedia. Neither of my parents had gone to college, but they believed strongly in education so we had quite a few books in the house, capped by the encyclopedia which "had everything!" I loved to read about the thinkers....the scientists, philosophers, and writers. And one day it occurred to me that these were the people who were remembered. Who made it into the book that "had everything." Later, at about age 10, I remember asking my Mom (at the height of the Vietnam War) why the world was so awful. She told me that there were a lot of problems that no one had solved yet, but that somewhere at the great universities there were probably people working on them. That sealed it. Who else but professors would have the time to sit around and try to make the world better? From there I guess it was a short step to philosophy, though that came much later. As a child I'd always been haunted by the problem of infinite space, and why I was a person born on Earth at this time and not some other time. It wasn't until I got to college that I realized these were philosophical issues. But when I did I said, "well, this feels like home."

3:16: One thing that has become very topical at the moment is the rise of science deniers and you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this. Flat earthers, anti-vaxxers, coronavirus truthers et al seem to prefer ideology to facts. So to start with, is there a common reason behind all these things, or is it a mistake to see them as being the same phenomenon? Are all these things coming from science denial or is it just that people think science is being used selectively for political purposes they don’t like rather than denying science?

LM: I think there is a common root behind all forms of science denial, and they all follow the same reasoning strategy too. A few years back the Hoofnagle brothers developed a five step strategy to explain how denialists reason: (1) cherry pick evidence, (2) reliance on conspiracy theories, (3) illogical reasoning, (4) rely on fake experts, (5) maintain that science has to be perfect. This flawed reasoning strategy is used by Flat Earthers, anti-vaxxers, evolution deniers, climate deniers, covid "hoaxers," GMO deniers, etc. Now I don't think it's true that all of these forms of science denial arise from the same ideology, but you're right that they each do arise from some ideology. In some instances this is political, but in others its economic, religious, etc. What happens is that someone values some belief that they love so much that when it is contradicted by science, they prefer to give up the science. So they aren't "anti-science" -- they believe other science -- just not the kind that questions their sacred belief. But it's also important to remember that science denial is not just the denial of some particular fact, but of the process by which scientific truths are discovered. Engaging in conspiracy theories, maintaining a double standard of evidence, cherry picking facts....those are anathema to scientific reasoning.

3:16: Why do you think that science denial is so important? After all, most people in the world haven’t a clue about science and believe all sorts of strange things – indeed a lot of scientists do too judging from the number of scientists who are also religious. Newton is a good example of this isn’t he – one of the greatest magicians of all time, and a deeply religious guy as well. We just seem good at holding contradictions.

LM: The danger of science denial is that it makes us feel justified in rejecting things that we don't want to believe as true, without sufficient evidence. And that can spill over. One thing you find with people who believe in conspiracy theories, for instance, is that if they believe one they believe twenty. Some may not seem dangerous, but others surely are. So I think it's important to hold the line in favor of rational belief, especially about empirical subjects. Why should we allow people to pick and choose what they are going to believe and what they aren't, as if science were a cafeteria? In fact I call such people "cafeteria skeptics" because they use science to justify what they want to believe, and then reject it when it steps on something else they prefer to be true. That can certainly happen to scientists too, but I'd hope that it is less likely. I take science denial seriously because in recent years it has gotten so bad that I think we're now in danger of living in a "denialist culture" where anything goes. And if you don't believe that, just look at the lie that Trump and 75 million Republican voters are pushing that the 2020 election was stolen.

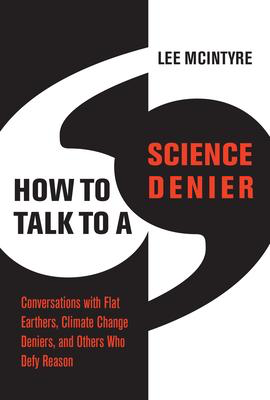

3:16: You’ve written about the sorts of things that should be done as a push back against the people denying science and holding conspiracy theories. Can you sketch for us some of the does and don’t of this- and why you think we should engage rather than just wait for it to dissipate?

LM: It won't dissipate. In fact, science denial is growing. It's a myth to think that if we just ignore the problem of science denial it will go away. Because what happens, especially these days, is that people's absurd beliefs are shared by a community of others -- who share misinformation with one another over the internet -- and that is a recipe for disaster. When one person believes a wild thing, they may give it up. But if they find a group of others who believe the same thing, then it's much harder to take it away from them. The important thing to remember in talking to conspiracy theorists is that it is not about evidence. How could it be? If there is any evidence in favor of a conspiracy theory, you can be sure they'll count it. But if there isn't any evidence -- and even if there is contradictory evidence -- they will usually claim that this just shows how clever the conspirators are! Now how in the world could you ever refute that with evidence? It can't be done. Instead, you have to remember that the reason the person you're talking to is a conspiracy theorist is that they have a broken sense of trust. By speaking to them patiently and calmly, even asking them to explain it to you, sometimes you can get them to realize the contradictions and absurdity of what they're saying. There is a great book on this by Mick West called Escaping the Rabbit Hole. There's another terrific book on conspiracy theory reasoning by Quassim Cassam called Conspiracy Theories.

3:16: Many people think there are strong arguments for toleration of beliefs that we don’t believe – Brian Leiter for example has argued for religious toleration even though he has no respect for religion. So are you arguing against toleration?

LM: Toleration is fine, when someone is committing to a personal belief that effects only them. But when it hurts the rest of us, I think there is a normative component to belief too. For instance, if we were out on a fishing boat and you didn't want to put on your life jacket because you felt that "God would provide" that is your choice. But if there was a storm coming up and you wanted to break the radio because "we can count on God to rescue us" then you've put me at risk too. To me, an awful lot of science denial seems like the latter. If someone believes in Flat Earth, I guess they're not really hurting anyone but themselves (although they are contributing to a denialist culture, which does hurt others). But what about disbelief in climate change or the Covid-19 vaccine? There I think I am justified in being intolerant because someone's irrational and false beliefs are putting the rest of us at risk. I'm not saying it's my right to sabotage their fire pit or force them to get an inoculation, but it is my right to challenge the kind of reasoning they are using and expose its flaws. They are making a decision that is not only irrational but immoral.

3:16: All this brings to the foreground the demarcation issue – what makes science distinctive? If everyone more or less agrees that there is no such thing as a scientific method then demarcation seems to be a matter of taste and ideology – and that defending science seems more like a shrill scientism than intellectual justification. First then, can you sketch for us the different models that have been proposed to make the demarcation and do you think any one of them will do the job? Just as positivism ended up denying itself, maybe science will end up denying there is science?

LM: Philosophers of science have spent the last 100 years -- basically since the founding of the field -- looking for a good criterion of demarcation that would neatly cleave science from non-science (or pseudoscience, depending on how you want to do it). They've failed. The best criteria were some of the earliest, by A.J. Ayer and the logical positivists, who came up with the "verification criteria." This basically said that if a statement was meaningful then there had to be some sort of empirical difference it made to your experience in the world. But, as you point out, it ultimately became a supreme embarrassment that even this failed to measure up to its own standard! The reasons for the demise of positivism are technical, but ultimately the problem is that they couldn't get past the problem of induction.

Next along came Karl Popper, who claimed that one did not need to solve the problem of induction, because science was in fact based on a form of deduction -- called modus tollens -- which allowed us not to verify a hypothesis but falsify it. This allowed a logic of science and -- Popper thought -- a solution to the demarcation problem. Now Popper himself didn't believe in scientific method. But he surely didn't believe it was just a matter of taste what counted as science and what didn't either. He believed in demarcation. But his own theory ran into problems as well (again, for some technical reasons here but, ironically, not unlike what happened to the positivists. His "falsification" began to look at lot like "verification" in disguise).

After that, the field floundered. Then in the late 20th century, Larry Laudan published a paper called "The Demise of the Demarcation Problem" in which he argued that it was basically unsolvable. That if we were going to solve it by now we would have. He offers some persuasive reasons for thinking that it will just prove impossible to provide a perfect set of necessary and sufficient conditions to solve the logical problem of demarcation. If you're using induction, there just isn't going to be a solution to it.

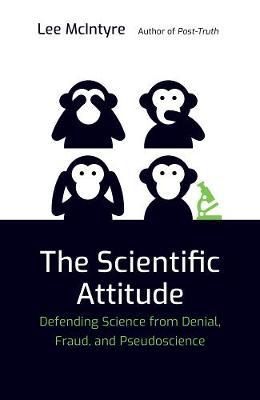

But now I think this has to be qualified. Because to say you're giving up on the problem of demarcation does NOT mean that you are giving up on the idea that there is something distinctive about science. In my book The Scientific Attitude, I offer the idea that what is really special about science is not its logic or method, but its attitude toward evidence. The scientific attitude is the idea that (1) scientists care about evidence and (2) they are willing to change their mind on the basis of new evidence. And that's it. That doesn't get you to a solution to the problem of demarcation, but it does preserve what I think of as Popper's central insight: that scientists care about testing a theory against the evidence. I think that's what makes science special. And, by the way, I think that allows us to have a tool box to push back against science denial, fraud, and pseudoscience as well. It's quite robust. Science is built around a community ethos whereby scientific practitioners check one another's work and keep one another honest even if they were honest in the first place. That is a rare and amazing thing. I wish more human reasoning worked like that.

3:16: Popper, the guy who started you being a philosopher of science famously thought that the social sciences couldn’t be sciences. What are we to do with science claims – that can’t be reduced to physics and that don’t have much by way of laws? Do the social sciences raise peculiar issues not pertinent to the natural sciences – just how different are the philosophical issues of biology or chemistry, for example, from economics or sociology?

LM: That is the topic of my dissertation! I won't give you the 400 page version, though, and will just sum up. When we talk about "reducing" to physics it's important to say what we mean. First there's the metaphysical question of whether any causes or laws at the secondary level entirely materially depend upon relationships at the primary level. Second is the question of whether -- if they do -- that means we would have to explain them totally on the basis of relationships at the primary level. Even for a non-conscious, non-self-aware subject matter, I don't think that even if (1) is true then (2) necessarily follows. There are many phenomena in chemistry for instance -- such as smell or transparency -- that are "emergent." What I mean by this is not that they are supernatural, just that they cannot be fully explained by physical relationships at the atomic level, because the descriptive terms that make something like "smell" meaningful only exist at the higher level of description. Could the same be true for human behavior? Absolutely.

And with human action, as you point out, we seem to have a rather peculiar problem. Do we have free will? Can we cause our own actions? Or should we just treat our thought as "epiphenomena" that arise on the occasion of a causal event between our brain and behavior? Human behavior has bedeviled scientists from the beginning. How can you predict, for instance, when the subject matter might hear you and alter its course of action? This is surely a weird factor. Even so, I don't think it's true at all that there are not or could not be laws of human behavior. They may not look like the laws of physics, but in fact -- especially in groups, but even as individuals -- our behavior is actually quite predictable.

3:16: Why do you think we should focus on failures rather than the successes of science to establish why science is so special?

LM: One problem with the history of science is that it spends so much time on the victories of science, of which there are many. But if we really want to understand why science works as it does, I think we can learn a lot from looking at scientific failure. Scientists make mistakes all the time, they recalibrate, change their minds, go down a bind alley and alter their hypothesis. That is part of doing science. If we try to understand science only by looking at its accomplishments -- like when Einstein's theory replaced Newton's -- then we get a skewed view. It's like drawing targets around where the arrows have landed. No one knows in advance how things are going to turn out. Science is uncertain. In the face of that, I think we have to spend some time thinking about failure. In fact, I think the main way you learn about what's special about science is to look at other fields that are trying, and failing, to become sciences. What are they doing wrong? You learn what science is at least in part by looking at what isn't science.

3:16: Linked to this is the hot topic of post-truth. What is post truth and why is it so horrendous? Is it a version of bullshit? It’s often linked with right wing fascist and populist agendas but it seems to have many familiar traits associated with left wing po mo positions too – Derrida and the constructivists and cultural relativists and identity politics etc etc - do you think there is a lefty zeitgeist informing this stuff as much as a right leaning one? It seems left populism is just as adept at using this tactic as the right populists.

LM: In my 2018 book Post-Truth, I define this concept as the "political subordination of reality." It is horrendous because it is in some ways the exact opposite of science. It's deciding in advance what you want to be true, and then trying to bend public to your side. But it is not a version of bullshit. If you read Harry Frankfurt, he quite clearly says that people who engage in bullshit do not care about truth. Well, post-truthers care a LOT about truth, because they are trying to control the narrative about what's true and what's not. A lot of them are authoritarians or their wannabes, who understand that the best way to control a population is to control the information they get. Historian Timothy Snyder said it best: "post-truth is pre-fascism."

Now it's a contentious question where post-truth comes from, but I think there are several roots. The main one is from science denial. Seventy years of awesome success by those who wished to deny the truth about evolution, climate change, etc., did not go unnoticed by political operatives. One day they said "hey, if you can lie about scientific facts, you can lie about anything." Like maybe the outcome of an election? And yes, I think that one of the other roots is post-modernism, which is largely left-wing. Now they didn't intend it. They were playing around with the idea that there was no such thing as objective truth, and that perhaps this meant that anyone making an assertion of truth was merely making a power grab. That all sounds fine when you're in the university doing literary criticism, but at a certain point these ideas began to create the "science wars," where humanists began to attack the idea of scientific truth. And from there, it leaked out even further and fell into the hands of right-wing political operatives. They picked up a weapon that had been left on the battlefield, and began to use it against some of the same people who had invented it. Post-modernists get irritated with me sometimes for "blaming" them for the Trumpian attack on reality, but all I'm really saying is that even if their intentions were good, they caused some damage. George Orwell said it best: "So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot."

3:16: All of this discussion seems to show that philosophy of science is important given that science is against bullshit, deniers and for truth. But why philosophy of science – why not just science? What if there are no questions left over once science is done?

LM: Most scientists are concerned with the study of empirical reality. They aren't by and large occupied with epistemic questions. And when they are, they often get it wrong. I see scientists out there defending themselves from deniers by saying that climate change has been "proven." That's the wrong approach. They know damn well that's not true. It's just very, very, very likely to be true given the evidence. But how do you say that, especially in a way that doesn't give the science denier a reason to go "aha!" That's where the philosophy of science comes in. We think about science as a way of knowing; we talk about warrant and justification. Those are useful tools for scientists to learn about. So yes I do think the kind of work that philosophy of science is doing is important work, and it's in service of defending scientists. But a lot of them are pretty ungrateful. Read Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg, Steven Hawking, etc. They all make some pretty unkind remarks about philosophers. The worst comes from one of my favorite scientists: Richard Feynman, who says roughly that the philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds. Well if that's true, why are scientists having such a tough time defending themselves these days when they get criticized by the general public? Yes, it's easy to say "these people aren't worth talking to" and go back to your lab a "be right." But what does that accomplish? The forces of denial are growing every day. I don't think now is the time for scientists to reject a little help.

3:16: Are there scientific laws or are there better ways of understanding scientific explanation? And if there are laws, what are they?

LM: There are laws. But what we mean by a law cannot be on par with exceptionless deductive certainty. Laws are well-confirmed regularities, that are confirmable by their instances, and support their counterfactuals. What does all that mean? I turned my dissertation into a book called Laws and Explanation in the Social Sciences, in which I argue not only that there are scientific laws, but that there are even laws governing human behavior. What are they? I wrote that book in 1996 and I don't think I've sold a copy lately. So I'm going to leave the audience in suspense.

3:16: As you've said, maybe some of the science deniers take their position because they are looking for certainty and science seems to fail in this department. Why should they take comfort from scientific causation, inexact laws and probabilities even if they fall short of certainty?

LM: Because those are the reality of studying empirical phenomena. If you believe that inductive reasoning is the basis for science -- and I think that you should -- then you understand that it is impossible for science ever to prove anything, or to achieve certainty. As I've written, I think that the most essential thing about science is to have the "scientific attitude," which is when you care about evidence and are open to changing your mind based on new evidence. Science isn't deductive logic. It can never close the books, no matter how good the evidence is. There is always a chance that some future piece of evidence can come in and overturn the applecart. And this is a good thing. It's what makes science special. Now I think a lot of people misunderstand this. Science deniers often insist on proof and certainty in science, and perhaps get impatient because they think it isn't living up to its own standards. So maybe you're right; they feel unfulfilled by "justification" and "warrant" and instead go looking for comfort (and certainty) elsewhere. Well good luck. Because if you can't find enough warrant in science, where are you going to find it? Probably in falsehood or delusion. People who believe things based on faith seem fairly certain. That may feel comforting, but it is a terrible way to learn about empirical reality.

And notice what's happening here. They're trading in a plethora of evidence -- that nonetheless falls short of proof -- for even less evidence, just because it makes them feel better. That's not science. Science denial isn't just rejection of certain inconvenient scientific facts, it's a rejection of the process by which scientists reason. Remember step five in the science deniers playbook? Insist that science has to be perfect? This is where that comes into play.

3:16: So are scientific theories just models – and how do these work? And don’t they leave us with a kind of anti-realism – a model universe is after all not the actual universe but simplified? Again, doesn’t this undermine science’s claim to be telling us the truth. ‘It’s just your model’, ‘your interpretation’ and so on deflates that claim doesn’t it? And given that physics seems to refuse to be able to read off an agreed ontology from its theories, aren’t truth claims again in trouble?

LM: I don't think we need to be afraid of anti-realism. I know those are fighting words. What I mean by that is this: a lot of philosophers think that the only way to defend science is to make the claim that it is discovering reality. That the evidence we gather is getting us closer and closer to truth which means that we are more and more justified in believing it. Well that's fine. And this is realism. They live and die by Hilary Putnam's idea that if what science is discovering isn't TRUE then it's a bloody miracle that it works so well. But I don't buy that at all. You're right that a model universe is not the actual universe. No theory is the thing that it is a theory of. A road map isn't the road either. Too bad. But there are better and worse theories and they are judged by their conformity with the evidence we get from reality. BUT THAT DOES NOT MEAN that we can ever be sure that we have found the TRUTH. And that is why I think realism fails. What I believe in is the doctrine of underdetermination. (One of my favorite papers on this is Helen Longino's "Underdetermination: A Dirty Little Secret?" In fact it is such a good paper that I'm going to provide a link to it here.) I believe that reality is consistent with many different descriptions of it, some of which offer good theories and some of which do not. But even among the ones that fit, there are many that might work. So how can we non-arbitrarily choose one and call that reality? That seems to me what the realists want to do. They are privileging the theories we now have over the ones we might have had, or might have in the future.

But why do that? One and the same reality can be described in different ways. And here remember that I am talking about accurate descriptions. Ones that work. But these support multiple accurate explanations of one and the same reality as well. Now doesn't this undermine the idea that science discovers the "truth." Yes, I suppose it does. But what is your alternative. No one ever said that inductive reasoning could lead you to truth. It can help you to eliminate falsehood (Popper's idea) but it can never say say "yes, now we have it, this is 100% accurate and no further evidence could overthrow it." Why not? Because that's not science. So if the complaint is that science is only the best possible way to know reality, but it still isn't perfect, then I don't know how to reply. It takes us back to Plato's cave. We see the phenomena as shadows on the wall, and they seem to have correlations to a reality that we can't see behind us. We describe the shadows, look for patterns, and use those to get closer to what we think is truth. But can we ever be sure that we know it? No. But too bad. That just how inductive reasoning works. It reminds me of the way that Winston Churchill once described democracy as "the worst form of government, except for all the others."

3:16: Hume set out for us the classic conundrum regarding induction – how far does a Bayesian probabilistic approach solve the problem?

LM: It doesn't. There is no solution to the problem of induction. Deborah Mayo has written the definitive text on criticisms of Bayesian reasoning. I understand that a lot of philosophers of science accept Bayes' Theorem as gospel, but there are potential problems with it. It sometimes surprises people to learn that there is a hot dispute right now in the philosophy of statistics over whether your starting assumptions should matter when you are going to gather a potentially unlimited amount of data. Again, Deborah Mayo pulls the curtain back in her book Error and the Growth of Experimental Knowledge. For me, I want to say that the scientific attitude works whether you are a Bayesian or a frequentist or something else. My only commitment is to the idea that for a scientist evidence counts. How you best reason on the basis of that evidence is a matter I shall leave to others.

3:16: You’ve worked on issues with the mad dog naturalist Alex Rosenberg. Are you a mad dog naturalist too – and equally proud to embrace scientism?

LM: That mad dog is my mentor and has grown to become one of my best friends. When I was in college I wrote him a letter and we've kept up ever since. But that doesn't mean we don't disagree on a number of philosophical issues, such as underdeterminism. I'm never sure what someone means by "naturalism." There are about three different things that philosophers might mean by "naturalism." In the past, I've often referred to myself as a methodological naturalist, because I believe that the methods of natural and social science should be identical. But I think you're asking about a more stringent version of naturalism: the idea that all phenomena at the secondary level can be explained by phenomena at the primary level. Some people take that all the way through physicalism, which is an epistemological commitment that comes out of a very sparse ontology. And there are other proud reductionists out there. But I'm not one of them. I believe that phenomena at the primary level (say atoms, or cells, or neurons) cause phenomena at the secondary level (say rocks, or humans, or consciousness), but that doesn't necessarily mean that we must explain them only -- or even preferably -- in the most reductive terms of this material relationship. But the reason is not that I think there is some other kind of mysterious extra-material causation going on....some phantom force. It's that I believe this whole question is really about the problem of explanation. And that means it's an epistemological matter, not an ontological one. So when we are trying to explain certain phenomena at the secondary level, we have to understand that even if they are metaphysically dependent upon relationships at the primary level, they are sometimes best explained at an autonomous level. Atoms or cells or neurons are not just "stuff" -- natural kinds -- even at the physical level. They are based on a description, and embedded in a theory. And that description and theory may be enlightening at one level, but not at another.

Take the issue of transparency that I mentioned before. That is an "emergent" phenomenon in chemistry. It is 100% dependent upon relationships at the atomic level, yet you could not explain it completely only in those terms. Transparency, smell, alienation, consciousness, revolution, life, monetary inflation.....those are concepts that exist only at the secondary level. And so I think they should be described and explained at that level too. Does that mean they can't be explained scientifically? Hardly. I think you can do science at many different levels of description. As I've said, I also believe that there could even by emergent laws in the social science. Does that make me someone who believes in scientism? I don't think so. But I am certainly a big fan of science.

3:16: And why do you think we’re in the dark ages about human behaviour and we should do something about it?

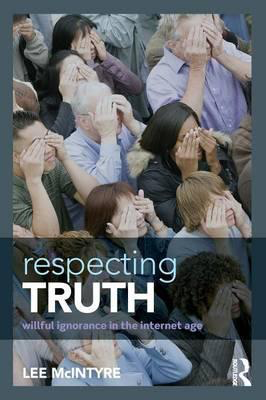

LM: One of my earlier books is called Dark Ages: The Case For A Science of Human Behaviour. In it, I argue that political ideology is doing to social science what religious ideology did to natural science round about the time of Galileo. I am against any kind of ideological interference in scientific reasoning. To me, "dark age" thinking is emblematic of the type of mind that wants an answer -- that wants certainty at all costs -- and damn when the evidence tells you you're wrong. To me, that's the mark of an incurious mind. Scientists may make mistakes sometimes, but I think their hearts are in the right place. But do you want to know something sad? I wrote Dark Ages with the idea that natural science was pretty solid, and we should build on that to come up with a better way to study and explain human behavior. Then, while that book was making the rounds, science denial started to heat up and suddenly people were attacking the results of natural science! To defend that I wrote another book Respecting Truth, in which I took on evolution deniers and climate change deniers, and tried to highlight the stupidity of their attacks. Couldn't they see that they weren't reasoning scientifically? Well then you know what happened. Things got worse from there. All of that unchecked science denial eventually metastasized into "post-truth"....into reality denial....under Trump. So my career has been marked by me wanting to defend science and extend it, and the world keeps pulling the rug out from under me and attacking science even where it is working. It's pretty depressing actually. I sometimes wonder if I'm making any difference, yet I can't give up the fight. When I was a kid and read that World Book Encyclopedia I used to mourn that I was born too late. All of the great ideas had already been discovered. Who was attacking science and reason now? All of the ideologues were dead. Boy was I wrong.

3:16: And finally, for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books other than your own that you can recommend?

LM: Other than the ones I've already mentioned?

Yes.... 1) Robert Trivers -- THE FOLLY OF FOOLS

2) Andy Norman -- MENTAL IMMUNITY

3) Stuart Firestein -- FAILURE

4) Eli Saslow -- RISING OUT OF HATRED

5) Jason Stanley -- HOW FASCISM WORKS I could editorialize and tell you why to read those five, but where's the fun in that? But take it from me, they are all gems.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

Joseph Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised

NEW: Reviews of new political books - A Hornbook of Democracy Book Reviews

NEW: Ernest Gellner Legacies series