Self-Determination and Ethics

Interview by Richard Marshall

'While some distance from or even outright scepticism about self-determination is typical in current moral theory, there is no comparable distance from reason. Modern ethics tends on the whole to avoid overt commitment to free will. But it is riddled with metaphysically unexplained claims about reasons and our responsiveness to them – about, in other words, reasons as exercising a power to move.'

'Self-determination is a power that we have over agency. Purposiveness is something quite different, a mode of intentionality.'

'Hobbes denied that there was such a thing as objective goodness that motivated us. All motivation came from prior attitudes as ordinary causes. Action was by its very nature an effect of a desire or appetite so to act as a means to various desired ends. The will was not a locus of agency but of passive motivations to act.'

'Voluntariness and purposiveness come to the same thing only if, as Hobbes supposed, actions cannot occur as attitudes. But why should we share Hobbes’s supposition?'

'A lot of people do find incompatibilism very intuitive. Not everyone does though, and it is not immediately obvious that those who are natural compatibilists are especially incompetent in their grasp of freedom and causation as concepts.'

'Hobbes’s sceptical argument is that there can be only one form of power, ordinary causation, because there is only one way in which causes determine outcomes - through the presence of the cause with its power necessitating production of the outcome determined.'

'Take away the very concept of power - of a capacity to produce or prevent outcomes – and there is nothing left to base a distinctively moral responsibility. But nor is there anything left of something very much part of our conception of rationality – a power of justifications to move us.'

Thomas Pink’s main interests are in ethics, philosophy of mind and action, philosophy of law and in medieval and early modern philosophy. here he discusses whether action matters in an ethically distinctive way, agency and self-determination, the revolutionary importance of Hobbes in this debate, his attack on the significance of free will and its ethical significance, the nature of moral blame, self-determination, purposiveness and action, motivation and volentariness, what Hobbes thought, whether freewill is conceptual, Galen Strawson, compatibility and incompatibilism, whether we have the power to determine alternatives, Hume's challenge and whether freedom is a power.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Thomas Pink: While initially reading history at Cambridge I took a paper on the history of political thought. Hegel’s Philosophy of Right was on the syllabus, so I spent my first summer at university reading Hegel’s Phenomenology. I had already been interested in philosophy at school, but I was so entranced that I decided to change subject. I became very interested in the interpretation of probability and wrote a PhD thesis on rational choice theory. After four years away working for a merchant bank in London, I returned to Cambridge to a research fellowship. Then began a longstanding interest not only in ethics, political and legal philosophy and in the philosophy of mind and action, but in the history of thought about these areas and especially in the period from 1500 to 1800, when so much in the philosophy of these subjects changed.

3:16: One area you’ve worked on is on questions regarding self-determination and normativity. So beginning with a general question that you face - does action matter ethically in a way that is distinctive, and if so how?

TP: It is natural to think that we are involved in ethics only because we are agents – only because we perform actions and refrain from performing them. If we were just intelligent trees, observing and feeling but never doing, our lives would not involve morality. When ordinary people are asked what morality is about, they will respond by talking about what you do – whether you give help to others when they need it, or only do things for yourself, and so forth.

But the significance of agency in morality is often downplayed by contemporary philosophers. Modern virtue ethics tends to insist that ethics is about excellence of character more than about actions and omissions. This is nothing new. Various philosophers in the past similarly downplayed agency too. A classic example is Hume, who thought that actions and omissions were simply effects and symptoms of what moral standards were really concerned with, which was our psychological motivations and capacities.

Even philosophers who do think that agency really matters in morality disagree about what agency is. Some think of agency as Hobbes did – as the voluntary, what we do on the basis of willing or desiring to do it, which they regard as distinct from our motivations and an effect of them. Whereas others think that agency matters in morality, but as a kind of inner performance, an inner agency of motivation or will. Stoic ethics seems to take this view.

So the question of the place of agency within morality clearly has two dimensions. The first is what agency itself involves, and how it relates to other aspects of the self. But the other is to do with the nature of morality and of moral standards, and how these govern the self. Morality involves standards that are normative – that make a call on us to meet them. But what do these standards address, and what is the basis of this call, and might it ever take a form specific to agency? At issue is the nature of ethical normativity itself.

I decided that a treatment of (as I called it) The Ethics of Action would need to fall into two parts, each of which could be read as a stand-alone book. One would be on the nature of action itself. This, already published with Oxford University Press and out now in paperback, is called Self-Determination because one clear reason why agency might be of special ethical importance could be that we can determine for ourselves what we do or refrain from doing, so that our agency is directly or immediately within our control as nothing else in our lives is.

The other, still being written, is called Normativity, because it is about the nature of ethical standards themselves. One important issue here is whether there is a kind of ethical standard, obligation or duty, that is specific to action and omission. Virtue ethics has tended to be sceptical of moral obligation, especially considered as a kind of demand on action, often dismissing it as an intrusion of ideas of law and punishment into morality. This worry is familiar to us now from Bernard Williams, with his sceptical account of what he called ‘the morality system’, or from much of the literature following Elizabeth Anscombe’s ‘Modern moral philosophy’. Again we find the issue already raised by Hume, who accepted the existence of moral duties, but who admitted them only as standards of virtue or moral admirability on motivation and character, not as directives on action itself.

3:16: These two questions, about agency and self-determination, and about ethical standards themselves, are often separated in contemporary work on ethics and freewill – is this something new, and does this separation pose dangers?

TP: Action theory and ethics tend to be distinct academic industries today. But that used not to be true. Major works on ethics once combined an account of ethics and of ethical standards with detailed theories of action and the various psychological capacities and powers connected with it. You find this in Catholic scholastics such as Thomas Aquinas or Francisco Suarez, but it is equally true of later writers hostile to scholasticism such as Thomas Hobbes and Samuel Pufendorf. Take Pufendorf’s On the Law of Nature and of Nations. Pufendorf was in a way a John Rawls figure in Protestant Europe around 1700, and his work was very important and influential – it was part of Hume’s reading as a law student at Edinburgh, and influenced him significantly. That book begins with a detailed account of the metaphysics of human agency, its freedom and its motivation – something you certainly don’t find today in John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice. A lot of modern action theory is equally detached from ethics. Even books specifically on free will often talk very generally about ‘moral responsibility’ but without any detailed attention to the nature of the standards we are responsible for meeting and the normativity that they involve.

Behind all this lies the revolutionary impact of Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes introduced deeply influential models both of action and of moral standards that were expressly designed to show both that self-determination in any significant form is simply not possible, and that anyway the issue of self-determination is irrelevant to moral theory. Indeed, this detachment of ethics from the metaphysics of agency and freedom is part of a more profound disconnection for which Hobbes was also responsible. This is a detachment of ethics from explicit concern with the metaphysics of power in general.

Power and the metaphysical questions it raises is thankfully becoming of greater interest to contemporary philosophers of science and nature. But it needs to be attended to by moral philosophers as well. Power is the capacity to produce or prevent outcomes, and one intuitive case of it is ordinary causation. Bricks when hurled at windows exercise a capacity to produce an outcome – the window breaks. That is why we think of them as exercising power or force. But there might be other kinds of power or outcome-productive capacity, and perhaps these too might very much matter within ethics.

One such power might be self-determination, as a power of freedom or free will leaving it up to us how we act. But there could be other ethically crucial forms of power – such as the power of reason to move us. Moral philosophers today tend to treat normativity as identical with reason. Ethical standards are taken to provide reasons for being moral, and in so far as we are rational, it is assumed that we can be moved by the reasons they provide. As Christine Korsgaard stated, ‘Thus it seems to be a requirement on practical reasons, that they be capable of motivating us’.

Now if reasons can move or guide us, that presupposes some sort of power that they exercise over us. They must have the capacity to produce in us as outcomes the attitudes and the actions that they justify. But you no more find contemporary moral philosophers investigating the nature of this power than you find them arguing about the metaphysics of self-determination. The difference is that while some distance from or even outright scepticism about self-determination is typical in current moral theory, there is no comparable distance from reason. Modern ethics tends on the whole to avoid overt commitment to free will. But it is riddled with metaphysically unexplained claims about reasons and our responsiveness to them – about, in other words, reasons as exercising a power to move.

The difficulty for current ethics is that Hobbes introduced assumptions about power that do not only threaten self-determination. They also threaten to make a power of reason to move us impossible as well. So if you do share Hobbes’s assumptions about power, and whether they know it or not most philosophers now do, but you still want to talk the language of reason and rationality, as most moral philosophers also want to do, you have a real problem.

One tactic is just to ignore the problem and to go on talking the reason talk while blithely ignoring the metaphysics. But that is just philosophical evasion. It would clearly be discreditable to try the same tactic in relation to self-determination – to talk the free will talk, but completely ignore the issue of its metaphysics. Now although such a quietism about free will has not prevailed, the same is not true for reason. So much has been bet on normativity as reason, that quietism about its metaphysics is a tolerated normal.

3:16: Hobbes attacks free will and its ethical significance doesn’t he? What’s his position and do you think he’s confused when he conflates a metaphysical account of the way the world is with a conceptual inquiry?

TP: Though Hobbes was a determinist, his attack on free will is not that of a lot of modern sceptics. He does not understand freedom in incompatibilist terms and then argue that because determinism is true, freedom is impossible. His scepticism was more profound. He claimed, rightly in my view, that (whether we take a compatibilist or incompatibilist view of it) self-determination in any form that could genuinely matter in morality would have to involve a power fundamentally unlike ordinary causation. Hobbes then argued that the only real power in nature, the only capacity to produce or prevent outcomes, is ordinary causation. Hence self-determination is impossible.

According to Hobbes, our actions are not products of any power of self-determination. The only power productive of actions is exercised not by agents themselves, but as ordinary causation by prior movements of matter, and most immediately by those such movements constitutive of desires or appetites. Actions by their very nature are effects of prior desires or appetites so to act as means to further desired ends.

Hobbes is known to most people now as a brilliantly original political theorist. His political theory depended, however, on a radically revisionary account of the self and of our conceptual life. Hobbes needed to establish not only that his political theory was the true one, but that it captured our ordinary understanding and, even more, that there could be no alternative understanding of the political. Hobbes did not want to allow that political institutions might be based on some alternative metaphysics of the self, such as that proposed by scholastic opponents like Francisco Suarez – a metaphysics that even if false, was still contentful, and as contentful might still, through being commonly believed, motivate and support a stable form of political authority.

So Hobbes insisted that his metaphysics provided not only a true account of the world, but also the very content of our ordinary thought, and indeed the only possible content that thought could ever have. His opponents’ rival ‘conceptions’ were not really possible conceptions. They were no better than destabilising verbiage. Hobbes linked truth in metaphysics to successful conceptual analysis in a very literal and direct way – something that (for different reasons) a lot of modern analytic philosophers have also tried to do.

But it really is not obvious that metaphysics and the analysis of our ordinary concepts are the same enterprise. Perhaps we can have thoughts that though metaphysically deeply mistaken, still have genuine content. Nor were the views of Hobbes’s opponents mere verbiage. In fact Hobbes showed a remarkably clear understanding of their meaning. That is why once you get past his implausible theory of content, his criticism of their rival metaphysics and psychology is often so interesting.

3:16: So why might action be the proper object of moral blame?

TP: Is moral responsibility for action and omission, or is it not a distinctive form of responsibility at all, and certainly not specifically for agency? This controversy depends on the nature of moral blame - the criticism which asserts that responsibility. Competing views of moral responsibility generally disagree about the nature of moral blame.

Neither Hobbes nor Hume believed that moral blame involved any distinctive form of responsibility, let alone one specific to agency, and they supported their view by claiming that blame is simply a form of negative evaluation. To blame someone is simply to criticise them for some form of badness. They then pointed out that you can rate people as bad for features of them that are nothing to do with their agency. Talentlessness, as Hume pointed out, is a form of badness, as when someone is a bad historian. Moral badness may be no different. A bad motivation or emotion that is none of the person’s doing could still make them bad, even contemptible, in moral terms.

You get more rationalist versions of the same argument about blame today, such as from Tim Scanlon, where this time moral blame is taken to be a form of rational criticism. The detachment of blame from agency is the same: things other than actions can make someone rationally criticisable, as unreasonable or irrational. They can have foolish beliefs or groundless fears. Moral responsibility is just another case of a general answerability to reason.

Now it is perfectly true that much moral criticism is like ordinary negative evaluation, or ordinary rational criticism. It is targeted at non-agency as much as agency. But there is such a thing as a distinctively moral form of blame, and a distinctively moral responsibility.

Ordinary negative evaluation or ordinary rational criticism criticises someone just in terms of their involvement in a faulty occurrence – an event in their life or a state of them is faulty, bad or unreasonable, and we criticise them simply for that event or state. They count as selfish just insofar as their motivations were selfish, or they count as foolish just insofar as their beliefs were foolish. But in moral blame we go further and raise the question whether the fault in them, the defective event or state, was their fault. Granted their motivation was selfish or their belief was foolish; but was it their fault that they had this selfish motivation or foolish belief? Moral blame asserts that it was, and this means that we move from criticism of someone as a mere bearer of defective events or states to someone as a determiner of them. The fault does not lie simply in events or states of their life, but in their power to determine those events and states. The fault occurred because they exercised this power, or because they had the power but failed to exercise it – and since its origin lies in the agent’s power to determine, the occurrence is not only a fault in the agent, but the agent’s fault. Not only was the agent selfish or foolish, but their selfishness or folly was their fault.

This is the obvious and familiar content of moral blame that Hobbes, Hume and Scanlon all ignore, but which the scholastics such as Aquinas recognised. The scholastics explained the tie of moral blame to agency in just this way - by appeal to moral blame’s presupposition of a power of self-determination, and then to the character of self-determination as a power over agency and the consequences of agency.

3:16: How do you see the relationship in a theory of action between a theory of self-determination and a theory of purposiveness?

TP: Self-determination is a power that we have over agency. Purposiveness is something quite different, a mode of intentionality.

To do something intentionally or deliberately is to do something for a purpose, as a means to a goal or end. Even if there is no further purpose to an action’s performance, we still think of the action as done for its own sake: it still has a purpose which lies in the action’s own performance as an end in itself. Similarly, omissions count as genuine agency, as intentional refrainings as opposed to simple failures to do anything, when they have a purpose. My lying still is a deliberate refraining, as opposed to my simply being immobile or out cold if, for example, I am remaining still in order to avoid detection by you.

Self-determination involves a relation between an agent exercising a power and the action as an outcome that they determine. Purposiveness, by contrast, does not of itself imply any exercise of power, but rather has to do with a rather different relation between the action and its goal, which is an object at which the action is directed. I go to the job interview at the City bank in order to become rich. The action’s goal, that I become rich, may of course never be attained. So the goal is an object of my thought, a mental object, and may never amount to anything more.

We have then the action involved in two quite different relations with quite distinct relata– with an agent exercising power to determine it, and with a mental object. Purposiveness seems to be a mode of intentionality, which is a general phenomenon extending beyond agency, and involves the agent’s possession of a range of psychological states or attitudes directed through their content at mental objects. There can be beliefs, which are a cognitive attitude to an object as true, or desires, an attitude of attraction to an object as good. Perhaps action is a practical attitude to an object as a goal – something good to be attained through this active and inherently purposive attitude taken towards it. That is one way of understanding agency and the purposiveness that constitutes it – a long established way, though not now the dominant theory, as we shall see.

Purposive agency looks as though it could occur without being produced by any exercise of power. Perhaps there could be a merely chance action, just as a desire or a belief could occur by chance. But there is a form of power that can be involved in purposiveness which is not the action’s determination by the agent. Indeed, this power seems almost contrary to self-determination. This is the power involved in motivation, when something about a goal moves the agent to pursue it. Rather than a power exercised by the agent over the action, motivation is a power to which the agent is subject along with their action. The agent is being moved by something else to perform the action. Perhaps if the motivating power is strong enough it can compel the agent into action, removing their power to determine for themselves what they do.

The contrast between self-determination and purposiveness is now obvious. Not only is purposiveness a mode of intentionality but it can involve a power that exists in potential tension with the power of self-determination, and to which the agent is subject.

What kind of power associated with the goal of an action might motivate its performance, inclining or even determining the agent to act? There seem in common sense psychology two possible forms it could take. One is a power in some way exercised by the object or goal of the action itself. I deliberate between various possible options – various possible goals that I could pursue. What moves me to decide on one goal rather than another might be its goodness or desirability. That is how I might justify my decision to you: that option, the goal I have decided on, is very good, or even the best thing to do. So it is the goodness of this goal that has moved me to decide on it.

This is a very natural way of putting things, and it involves a model of reason. As a rational or reasonable being I pursue goals to the extent that they are good. Their goodness justifies their pursuit and is what moves me to decide on them. This practical rationality corresponds to a similar production of belief through theoretical reason, only here what moves me is not the good but the true. The evident nature of a claim, its likely truth, moves me to believe it. We arrive at a theory of reason as involving potential objects of our mental states, when we consider them in our deliberation, moving us to form attitudes to them that they justify by virtue of their normative character, such as their likely truth or their goodness. Rationality, being moved by reason, involves (on this model) a kind of normative power, based on values such as truth or goodness, exercised over us through objects of our thought.

But there is a quite different way of thinking about motivation, which is clearly also present in common sense psychology. This takes the motivation to be provided not by the goal itself but by some prior attitude towards it. What moves me to act for an end might not be the goodness of that end, but a simple desire to attain it.

The scholastic tradition certainly did allow that motivation for agency could and did come from prior attitudes. But insofar as we were rational, the fundamental source of motivation was through a normative power of goodness, a power by which we were attracted or drawn to decide to do this rather than that. Linked to this view of motivation was the view of purposive agency already mentioned, as a distinctive mode of intentionality. Action in its immediate or primary form occurs as a distinctively practical and purposive attitude – a content-bearing attitude of the will in which we decide on something as our goal.

By contrast Hobbes denied that there was such a thing as objective goodness that motivated us. All motivation came from prior attitudes as ordinary causes. Action was by its very nature an effect of a desire or appetite so to act as a means to various desired ends. The will was not a locus of agency but of passive motivations to act. Actions were not a practical kind of attitude. Indeed, actions were not attitudes at all, but expressions and effects of attitudes, the motivating attitudes that caused them. Agency was restricted to allegedly contentless movements of one’s limbs and the like, such as intentionally raising one’s hand, as effects of content-bearing passive appetites so to act.

The goal of an action was not a mental object at which it was directed by virtue of its own content. Instead an action’s goal-direction was entirely provided by the contents of prior attitudes that caused it, and that left it desired either for its own sake or as a means to further ends. On the Hobbesian theory attitudes are one thing, actions quite another, and goal-direction always presupposes an action’s motivation, through ordinary causation, by attitudes that are passive. Hobbes identified agency entirely with the voluntary – with what we do on the basis of holding motivating pro attitudes (such as desires) towards its performance.

This Hobbesean theory of actions not as attitudes but as effects of attitudes still dominates. It is, for example, Davidson’s view too.

3:16: What is the relation between motivation and voluntariness, and how might motivation explain what we do voluntarily? If motivation is non-voluntary, does that include decisions and intentions? Is Hobbes right to suppose that decisions and intentions are not voluntary?

TP: We can distinguish between the attitudes motivating an agent and what the agent does on the basis of those attitudes. Someone wants or intends to do something – to produce some outcome. And if successful in what they do, they produce the outcome intended or desired. This production of outcomes on the basis of a motivation to do so is what Hobbes meant by voluntary action, and, as I’ve already mentioned, he thought that voluntariness was the only form in which action occurred.

Everyone admits that agency occurs at the very least as voluntariness – as doing things on the basis of wanting to do them. But is that the only form taken by agency? Perhaps not if, as common-sense psychology seems to assume, some motivations – not mere desires but decisions to act – are actions.

Some philosophers, however, are tempted to make room for these actions of motivation or will while still retaining Hobbes’s identification of agency with voluntariness. So Harry Frankfurt writes as if a higher order voluntariness of desire were possible – as if we could form desires on the basis of desires so to desire as we might raise our hand on the basis of desiring so to act. But it looks as if motivating attitudes are not themselves voluntary. As Hobbes put it: ‘I can act as I will; but to say I can will as I will is absurd speech’. The point seems to hold just as much for intuitively active decisions and intention-formations as for passive appetites or desires.

Why is this? It seems to have to do with the nature of motivations as content-bearing states. Decisions, like beliefs and desires, are attitudes with mental objects. What gets us to form these attitudes is not their own general consequences and the desirability of these, but (it seems) the character of their objects – those objects’ likely truth in the case of belief, their goodness or desirability in the case of desires or decisions. Gregory Kavka’s famous toxin puzzle about a huge prize offered just for taking a decision illustrates this. No matter how great the prize, if the decision is to perform an action that is obviously rather undesirable, or which the agent does not want to perform, such as drinking a mild toxin, the prize offer, which simply rewards the decision whether or not it is executed, won’t move us to take it, any more than belief prizes will move us to form beliefs that clearly go against the evidence.

3:16: Is Hobbes right to think that to do something as a means to an end is to do it on the basis of a will to do it, and so as an effect of passive pro attitudes towards doing it?

TH: Hobbes thought that purposiveness implied voluntariness precisely because he restricted purposive agency to what we clearly do voluntarily – to the production of outcomes on the basis of prior motivations so to act. But if purposive agency also occurs as a non-voluntary attitude, as an action of the will, a decision to act, we need to explain purposiveness in a way consistent with that. And there is one way to do this – as I’ve already suggested, through the theory of intentionality. The purposiveness of an attitude must consist in being directed at its object as a goal – where the rationality of the attitude depends not only on the goodness of its object but on a sufficient likelihood of the attitude attaining that object. And that, I’ve argued, is just how we understand decision rationality. The rationality of deciding to do A depends not only on the goodness or desirability of doing A, but on whether the decision is likely enough to get us to do A. There is no rational point taking a decision to do something if taking that decision is sure to have no effect on whether we do it. That still leaves decisions non-voluntary. We still cannot take decisions simply because we find the decision itself desirable in other ways, say as a means to winning a prize just for taking it.

Voluntariness and purposiveness come to the same thing only if, as Hobbes supposed, actions cannot occur as attitudes. But why should we share Hobbes’s supposition? I argue in Self-Determination that a plausible view of intentionality provides no support for Hobbes’s narrow view of it – for his restricting it to cognitions and passive desires, denying that there are practical or action-constitutive attitudes too, such as decisions of the will.

But then there is the view of motivation that historically came with the doctrine that actions can occur as attitudes. This is the scholastic view that motivation for these attitudes may be provided by their objects. The goodness of an object of our thought canmove us to decide on it as our goal. This scholastic view is, as I have already noted, a theory of how reason might move us practically. Is it plausible? And, plausible or not, is it anyway our ordinary understanding of how reason moves us?

The question of rational motivation is one I shall be discussing in Normativity. Central to the idea of reason seems to be a kind of normative direction, provided by justifications, by which we are guided as rational beings. Reason or reasons somehow move us to form the attitudes that are reasonable or justified. But how to model this thought?

There is the scholastic view of objects of thought exercising normative power. But Hobbes’s discrediting of this theory was immensely effective, and over the century that followed this critique led to a crisis in the theory of normativity that is still not well understood by historians of philosophy, and that Normativity will discuss in detail – a crisis that led both to Hume and to Kant. Are there alternative models of how reason moves us that avoid the problematic metaphysics of scholastic theories of reason? Or is the very idea of reason as something that can motivate us something we should just give up?

3:16: Is Galen Strawson right to argue that our very concept of freedom is taken to be an incompatibilist one and then infer freedom’s unreality from this incompatibilism?

TP: The debate between incompatibilists and compatibilists is about the compatibility of self-determination or freedom as a power of the agent with the operation on the agent of another power – causal power exercised over us by prior occurrences outside our control. In a world that was causally deterministic, where our every action was predetermined by such causes, would we still have a freedom to do otherwise?

In assuming that incompatibilism, if true at all, is a conceptual truth, Galen Strawson is entirely representative of a wider modern consensus. This is that this free will problem is entirely conceptual. The problem has to be solved one way or the other without reference to experience, just by thinking about the concepts of the powers concerned, causation and freedom. All the debate is simply about which way the conceptual argument then goes. The incompatibilists insist that if you take a set of platitudes supposedly shared by everyone who grasps the concepts of freedom and causation, these will entail the incompatibility of causal determinism and freedom. The compatibilists insist that such a set of platitudes will deliver the opposite result.

But why assume that the problem is conceptual? Some questions about powers and their properties may of course be conceptual. But not all, obviously, otherwise we could investigate causal power in nature just by reflecting on the concept of causation and do natural science from the armchair, without ever having to look or experiment. When the question arises of the compatibility of one power with another – does the operation of one force block the operation of another? - we often have to consult experience. Where freedom and power attaching to prior causes are concerned, this may be another such case.

A lot of people do find incompatibilism very intuitive. Not everyone does though, and it is not immediately obvious that those who are natural compatibilists are especially incompetent in their grasp of freedom and causation as concepts. Furthermore, the attempts of both sides to go beyond hand-waving assertion and actually prove their case conceptually have not gone well. Incompatibilists have tended to rely on Van Inwagen’s Consequence Argument; but compatibilists like David Lewis have had no trouble in exposing the question-begging nature of that. On the other hand, compatibilist attempts at conceptual ‘reductions’ of freedom to forms of ordinary causation – cases of ordinary causal power immediately consistent with causal determinism - are far from compelling either. It is not especially plausible, to take a classic example of such a reduction, that freedom is just for one’s actions to be determined by one’s desires.

In Self-Determination I argue that incompatibilist intuitions come not from our concepts but from experience and the imagination – from the way that the relationship between freedom and prior causation is presented phenomenologically. We have to acknowledge that certain cases of power, and of relations between distinct powers, can be represented in experience – something that since Hume has often been assumed impossible. As I argue in Self-Determination, since Hume and Kant the theory of freedom has become separated from phenomenology in ways that simply are not justified by any plausible theory of experience and the imagination. Whether experience represents power to us veridicallyis however a further question. The difficulty of answering that question leaves me agnostic about the compatibility of freedom with causal determinism.

[Hobbes]

3:16: What do you make of another kind of scepticism, one that doubts there is any such power to determine alternatives?

TP: Unlike incompatibilism, the power to determine alternatives does seem essential to our basic understanding of what freedom is. The very expression we use in English to report our control of how we act has this power to determine alternatives baked in. “It is up to me whether I raise my hand or lower it” – the very syntax of that expression ‘up to me whether…or…’ serves to report a plurality of contrary outcomes that I can determine and that are thereby left ‘up to me’. It is significant that Hobbes concentrated his scepticism on the power to determine alternatives, not on the issue of incompatibilism. Hobbes’s problem is with the very particular conception of determination that a power to determine alternatives implies.

The general idea of a determining power is clear enough. A power determines an outcome only if given the operation of the power there is no further dependence of the outcome on chance. Not all power need so determine outcomes when it operates to produce them. Probabilistic causation involves power that is not determining. Where the cause is merely probabilistic it influences towards a given outcome, but even given the operation of its power the outcome can still depend on chance. I throw a probabilistic brick at a window and the operation of its force might determine that the window cracks. But though the force of the brick is clearly operative, whether the window actually breaks might still depend on chance. This is the picture of causal influence that libertarians rely on to reconcile the evident influence of our desires and emotions over our actions with those actions remaining free. Even though our desires seem to be exercising a causal power over us – we feel ourselves being inclined by them to act one way rather than another - how we act can still be left open, so that it is left to another power, our own freedom, to determine whether or not we finally act as our desires incline us to.

Now it is very clear how ordinary causes determine, as Hobbes well knew. If a cause, the brick hitting the window, really does have the power then to determine that the window not only cracks but breaks, then given the presence of the cause with its power, the window must break. If the window does not actually break then any window-breaking power possessed by the brick under those conditions cannot be determining. At best the brick has a power that is probabilistic, and whether the window actually breaks still depends on chance.

But freedom as a power to determine alternatives cannot work like that. For then, as Hobbes pointed out, an agent with the power under given conditions to determine more than one outcome would have actually to produce both, which is impossible. The problem that Hobbes is exposing is this. With ordinary causation there are two possibilities. Either the operation of a cause’s power is open, so that a given outcome might or might not arise. But then we think of the cause as lacking power, in the sense that it at best influences what happens, and the rest is left to chance. Or the cause is not lacking in power then to produce the outcome, in which case its operation is not left open at all. Given the presence of the cause, the very nature of its power (as a power then to determine that outcome) necessitates the outcome’s production. Either causes lack power, or they operate in the fixed and inevitable way of a cog within a mechanism.

But with freedom this is not the case. An agent can exercise his power to determine exactly how he acts, but the nature of the power still leaves its operation open. That is the nature of freedom – it is a power to determine action, where whether or how the agent exercises it is left up to him, and not fixed by the very nature of the power. Instead of the power’s operation being necessitated by its very nature as a determining power, its operation is left contingent. Freedom is a power to determine contingently.

Hobbes’s sceptical argument is that there can be only one form of power, ordinary causation, because there is only one way in which causes determine outcomes - through the presence of the cause with its power necessitating production of the outcome determined. Notice this is really nothing to do with assuming incompatibilism. It is one question how a power determines outcomes when it does so. It is another question whether the operation of the power itself can ever be causally determined.

Hobbes may not be right about how determining power can work. He thought he could show that what I call contingent determination was impossible. There cannot be a power that determines outcomes without necessitating their occurrence, and where whether and how the power operates is left up to its possessor. But I argue in Self-Determination that Hobbes failed to show this.

3:16: Hume argued that if you remove causal necessity from human action you’re left with just randomness rather than freedom. How do you respond to the Humean challenge?

TP: Hume is of course right if ordinary causation is the only power operative in nature. Then an action that is not necessitated by prior causes is not determined by any power. Its occurrence must depend on mere chance; it must be random. But if there can be a power that determines contingently, Hume’s claim is just false. An agent can determine how he acts, so that given the exercise of his power how he acts is not left to chance. But whether and how he exercised the power can still have been left open both by the nature of the power itself and by prior causes.

3:16: So as a take home, how do you conceive of freedom? Is it a power?

TP: To the extent that freedom matters in ethics as a feature of the self, it clearly matters as a power. Moral blame seems to be a distinctive criticism, asserting a distinctive form of responsibility, only because its content presupposes a power of agents to determine for themselves what they do. Intuitions about the compatibility or otherwise of freedom with causal determinism are inescapably intuitions about the relations between distinct cases of power, and these intuitions reflect how such powers and their relations are represented in experience and in the imagination. We only believe that it is ‘up to us’ how we act because experience represents this to us as our possession of a form of power.

Take away the very concept of power - of a capacity to produce or prevent outcomes – and there is nothing left to base a distinctively moral responsibility. But nor is there anything left of something very much part of our conception of rationality – a power of justifications to move us.

This is why Hume’s ethical theory is so important. Of course, Hume seems to have been generally sceptical about power as a feature of nature, or at least about our having any genuine understanding of such a thing. That seems to be the import of his famous arguments about our idea of causation. Beyond that, I shall be arguing in Normativity, he had inherited from predecessors such as Hobbes and Francis Hutcheson a project of detaching ethical theory from certain especially problematic forms of power - not only from appeal to a power of self-determination or freedom, but also from appeal to a normative power of reason. That seems to me to lie at the heart of Hume’s scepticism about practical reason. Can we make sense of ethical normativity without such distinctive forms of power, and what price has to be paid in giving them up? For that is what the Humean theory of moral normativity without reason will involve, as a normativity instead of merit or personal admirability, as Normativity will explain.

3:16: And finally, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

TP: I shall cheat and recommend five authors. Two of these authors make especially fascinating contributions, but in each case these extend over more than one book.

Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologiae, especially the prima secundae– a profound and vastly influential presentation, within the scholastic tradition, of a theory of happiness, agency, motivation, virtue and obligation.

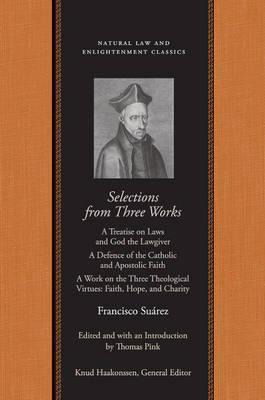

Francisco Suarez Metaphysical Disputations– especially the treatment of explanation and of the Aristotelian causes through disputations 12-27, with their searching presentation of a theory of power and its role in ethics that Hobbes both clearly understood and relentlessly opposed; and On Laws and God the Legislator– an examination of the use of the notions of obligation, direction and responsibility in morality as compared to their use in human legal systems, all of which bases a fascinating theory of law and the state: a highly sophisticated version of the political theory that Hobbes sought to destroy.

(There is a translation edited by A.J. Freddoso of disputations 17-19 on efficient causation, including the power of freedom, in Francisco Suarez, S.J.: On Efficient Causation (Yale University Press 1994).

And I have edited a series of translations from On Laws in Francisco Suarez: Selections from Three Works(Liberty Fund 2015).)

Thomas Hobbes The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance – a polemical statement, in debate with the scholastic John Bramhall, of the theory of psychology, agency and power that provided the basis for the political theory of Leviathan. This book created the free will problem in its modern form.

(I am currently working on an edition of The Questions for the Clarendon edition of the works of Thomas Hobbes.)

David Hume A Treatise of Human Nature and An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals The discussions of will, agency, and practical reason in book two, on the passions, of the Treatise,and of moral normativity in both these two works provide a very innovative account of how normativity might not take the form of reason at all, but consist in merit or personal admirability instead.

Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy The book of contemporary ethics that I most admire. This book persuaded me to abandon rational choice theory and to return to an historical approach to ethics, and to view scepticism about reason as a central issue.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees