Smoke and Flickering Shadows: Strawson and Evans on Truth and Factuality

By Huw Price

I first discovered this fascinating conversation as a postdoc at ANU, Canberra, in the early 1980s. I was interested in truth, and looking for new things to read. Google was nearly 20 years in the future, so I had to rely on the library’s subject catalogue. This worked much like Google does today, with two differences. I had to look up ‘Truth’ in a large device called a card catalogue, rather than typing it into a search field. And the results – accessible instantaneously in the card file, just behind the ‘Truth’ card – were limited to items held by the library.

In amongst the listings for books, there was one for a movie – as the card told me, a discussion between P F Strawson and Gareth Evans, recorded for The Open University in 1973. The library had a copy on 16mm. That sounded intriguing.

Fortunately, unlike some postdocs today, I knew how to use a 16mm projector – I was a projectionist first, a projectivist second. I organised a screening for colleagues and graduate students, and was delighted to discover that Strawson and Evans’ discussion connected to my own interests in truth and factuality.

At the end of the 1980s I moved to the University of Sydney. There, too, the library had a copy. I soon organised another screening, perhaps for a graduate seminar. By this time I had published a book on truth and factuality (Facts and the Function of Truth, Blackwell, 1988), and the relevance of Strawson and Evans’ discussion must have been even more salient to me.

The next encounter I remember was in October 2005. Bob Brandom was visiting Australia, and I organised a one-day conference with him at the University of Sydney. Guessing that he would not know this little piece of philosophical history, I advertised a Mystery Movie, and screened it between his keynote and dinner. He pressed me for a digital copy, to give to John McDowell, and that was the beginning of the project of liberating the conversation from its 16mm obscurity.

I didn’t have a means to digitize it at that point, so it went back to the library. Fortuitously, I asked to borrow it again, to screen at another conference, just as the library decided to dispose of its entire collection of 16mm films. They gave me their copy, saving it from the flames, or at least from landfill. The University’s AV department had a similar view of the value of its 16mm projectors, so I acquired one of those, too. With these resources, and the assistance of my colleague David Braddon-Mitchell, I soon had a reasonable digital version. It has been available on YouTube since 2012.

Recently, one of my Covid-19 lockdown projects has been to write a new Introduction for a forthcoming Second Edition of Facts and the Function of Truth.Trying to reconstruct my own sense of the philosophical landscape in the early 1980s, I watched the Strawson and Evans discussion again. As usual, I was struck by how fresh it seems. Exactly the same issues are in the air today, in some ways. I realised that it would be simple to have a transcript produced, to make the conversation more accessible (and citable). The full textis now available on PhilPapers.

Strawson and Evans begin with the ‘thin’ conception of truth we have from F P Ramsey. Ten minutes into their conversation, as Strawson finishes his cigarette, they connect it to the intuitive distinction between factual and non-factual uses of language. On one side are genuine claims about the world – ‘statements in the strict sense’, as Strawson puts it. On the other side are utterances of various other kinds – as Strawson says, utterances ‘which play a different role in our lives from that of stating or purporting to state how things are in the world’. In the latter category they mention mathematical and moral claims, as well as questions and commands.

It seems natural to draw this factual/non-factual distinction in terms of truth. Genuinely factual utterances are ones the world makes genuinely true or false. At best, other utterances are entitled to some sort of derivative kind of truth. But as Strawson and Evans point out, Ramsey’s thin kind of truth doesn’t seem able to mark such a distinction – it doesn’t seem substantialenough, as Bernard Williams had put it a few years earlier. In ‘Consistency and Realism’ (1966) Williams notes that if in ‘saying “P is true” we merely confirm, re-assert, or express agreement with P’ – as Ramsey’s remarks suggest, and as Strawson himself had arguedat one point – then it could not ‘be more than an accident of language that “is true” signified agreement with assertions rather than agreement with anything else’.

Strawson and Evans agree that Ramsey’s thin but attractive notion of truth can’t draw the factual/non-factual distinction. They close by asking where that leads us. Evans suggests that an appeal to belief might do the trick – genuine factual claims might be those that are ‘a proper object of belief’. Strawson replies that in his view, the same ‘obscurity’ about ‘the coverage of true or false’ may well ‘extend also to … the coverage of belief’.

Remarkably, these issues are as salient – and difficult – today as they were 50 years ago. In the spirit of continuing an all-too-brief conversation from that era, this series of commentaries will offer contemporary perspectives on the topics that Strawson and Evans discuss, from a range of leading scholars.

Afterword: Concerning the actual conversation in 1973, Crispin Wright once told me that he played squash with Gareth Evans the morning before it was recorded, and that Evans was feeling nervous in prospect. More poignantly, Galen Strawson told me recently that the conversation itself had to be repeated, because the cameraman forgot to put film in the camera – and that Strawson and Evans felt that the first take was better. Even in the version we have, the conversation reminds us how much philosophy lost when Evans died, tragically young, in 1980. It seems an additional blow that these flickering shadows are one step further removed from the original.

The series so far:

Derek Matravers and Dan Cavedon-Taylor

Dorit Bar-On and Keith Simmons

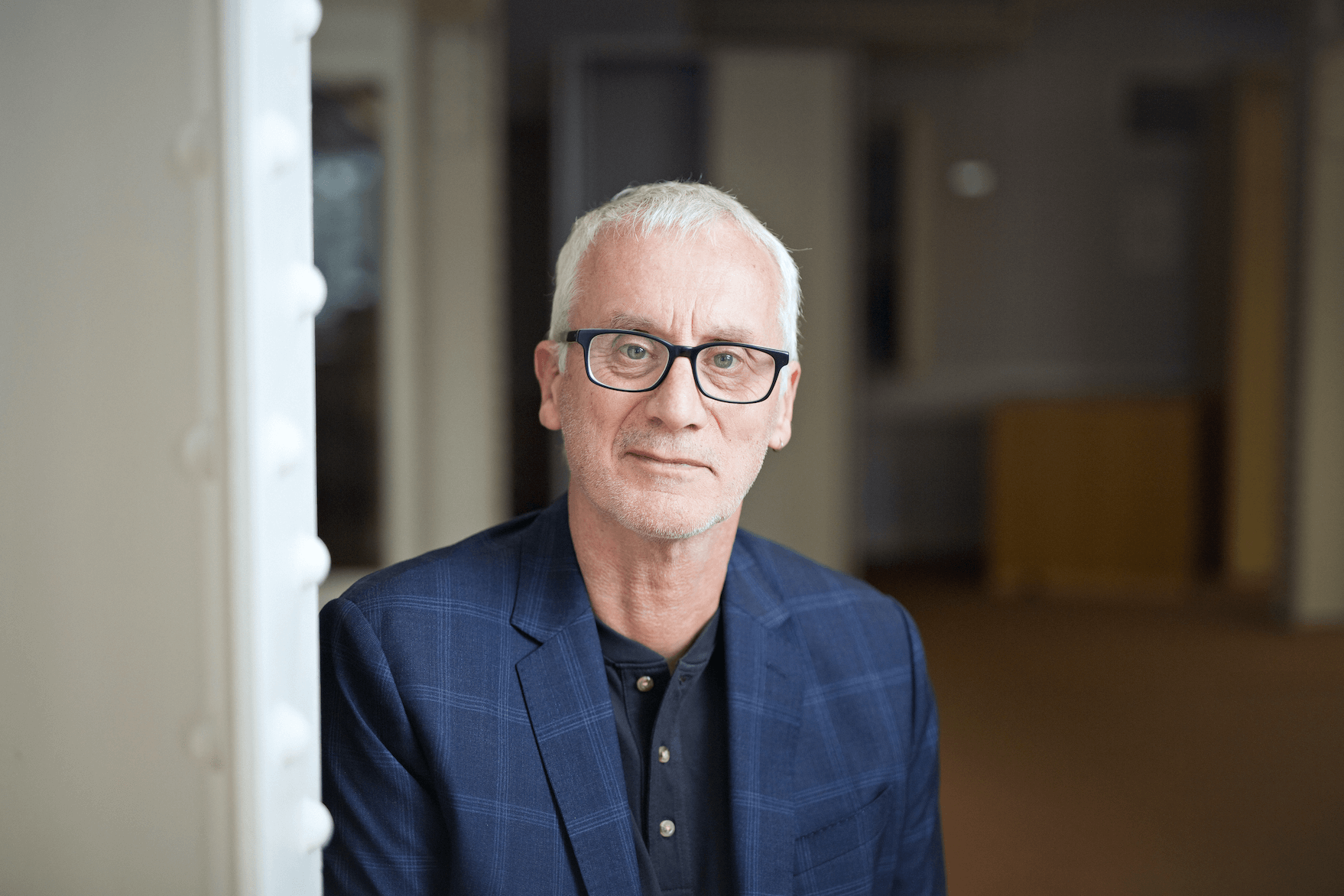

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Huw Price is Bertrand Russell Professor of Philosophy and a Fellow of Trinity College Cambridge . He is Academic Director of the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, and was co-founder with Martin Rees and Jaan Tallinn of the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. In January 2019 he joined the inaugural Board of the new Ada Lovelace Institute. Before moving to Cambridge in 2011 he was ARC Federation Fellow and Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney, where he was founding Director of the Centre for Time. His books include:

Expressivism, Pragmatism and Representationalism

Causation, Physics, and the Constitution of Reality

Time's Arrow and Archimedes' Point