The Philosophy of Jazz , Popular Music and Art

Interview by Richard Marshall

'Adorno’s concerns about the development of a commercial “culture industry” led him to think that the Black elements of jazz and popular music are there because they’ve been appropriated or co-opted by the industry for marketing purposes. The seemingly-important musical difference between, say, Louis Armstrong and Thelonious Monk are really no more significant than the introduction of colored sparkles into a commercial powdered detergent in order to be able to market it as new and improved.'

'The issue, in compressed form, is that either we need to stop thinking that all musical works are ontologically of one kind, or we have to think of many improvisations as performances of inferior, sloppy compositions, or we have to say that, when musicians improvise, the music has no distinct identity other than occurring at that time and place. I favor the first of these choices, which requires a rethinking of Goodman’s classification scheme.'

'Aesthetic judgment permeates our human world, and we have an endless number of types of things that invite philosophical reflection without ever talking about art. In short, we might do a better job of understanding the nature of aesthetic value and the complexity of our aesthetic vocabulary by ignoring art.'

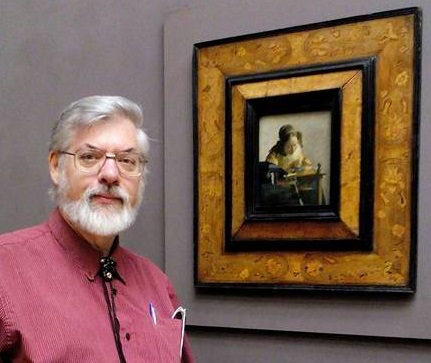

Theodore Gracyk is a philosopher of the Aesthetics of Music, the Philosophy of Art and the History of Modern Philosophy. Here he discusses the philosophy of jazz, why heed a philosopher regarding jazz (or anything), whether a unified definition of jazz can be given, jazz and race and gender, jazz as Nietzschean Dionysian festival, the interface between jazz and white minstrelsy, blackface, and appropriation, the politics of identity and appropriation raised by rock music, improvisation, Nelson Goodman, can improvisation be flawed, is all music art, do ideas imposed on art interefere with aesthetic responses, contextualisation, the distinction between art and aesthetic and analytic/continental approaches.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Theodore Gracyk: I had limited exposure to philosophy prior to college. My goal was to go to law school, thinking that I’d pursue a career in copyright law. But I quickly became bored with the college major I originally selected toward that end—political science—and realized that the course that I enjoyed the most was my philosophy course, one that had been selected for me as a general education course. This was at the University of Southern California, where I felt alienated by the experience of attending huge lectures where we interacted with teaching assistants but never the professors. My frosh philosophy course, on the other hand, was a small seminar. That was such a better experience, and so much more fun than taking notes in lecture hall, that I transferred from USC to St. Mary’s College of California, which built general education around the “Great Books” program and every course was a small seminar. Another part of my motivation to transfer was to return to the San Francisco area, where I was born and (mostly) raised. At that point I switched to philosophy, which meant that my undergraduate philosophy work focused on Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, and phenomenology and existentialism. I also got my first taste of philosophy of art, from a Continental perspective. I also encountered Hume for the first time, as a component of an English lit seminar on the history of literary criticism. I was still planning to apply to law school, but by my senior year and I decided philosophy was just too much fun, and took the GRE instead of the LSAT. Ironically, I regularly earned money during my grad school years teaching LSAT preparation sessions to students preparing for law school. My first year of grad school, at UC Davis, confirmed that my head and heart were in philosophy, so it became my career path. Initially, I continued to emphasize Classical Philosophy and Continental (especially Heidegger), but the preparations from my comprehensive prelim exams shifted me toward eighteenth century philosophy and analytic epistemology and value theory.

3:16: You’ve written about the philosophy of jazz music, which makes a refreshing change from the usual Beethoven, Wagner examples we get discussed in other philosophy of music books. Why jazz, and is the move to a specific area of music you taking up Peter Kivy’s thought that we’d be better off if we stopped thinking of art as a monolith and paid greater attention to its multifarious ways and means?

TG: Peter Kivy was an enormous influence, and I attended his presidential address to the American Philosophical Association in 1992, where he first made that argument. But the idea can also be found in his earlier work, and I’d already internalized it, rather obviously, in my first monograph, Rhythm and Noise: An Aesthetics of Rock (Duke University Press, 1996), where I argued that most of what we take to be universally true of music is largely true of Western art music, and it gives us little or no insight into the operations of most music, especially recent popular music.

Anyone who reads my first monograph is likely to notice that my discussion of recorded music borrows from philosophy of film. I earned some pocket change as a film and music critic on college and local newspapers during both my undergrad and grad school years, and I’d read a lot of film theory and some philosophy of film, and had always been struck by how special film is as an artistic medium. So, why philosophy of jazz? Ironically, it was partly due to the fact that my first two papers on popular music were rejected, with very little explanation, by the journal that I now co-edit: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. With the exception of some work by Richard Shusterman, the only philosophy of music that was being published that was positive about popular music was about jazz, so I turned my attention there. Thinking about philosophical antipathy toward popular music, I decided to examine one source of it, the writings of Theodor Adorno, which led to an important early publication, 1992’s "Adorno, Jazz, and the Aesthetics of Popular Music.” It appeared in The Musical Quarterly and brought my work to the attention of musicologists as well as philosophers, and that’s paid off in many fruitful interactions in the years since.

But the decision to write about jazz was not simply pragmatic. My older brother became a jazz fan in high school, and he was constantly listening to Miles Davis and John Coltrane along with rock music, from Cream to Zappa. If both parents were at work, that meant high volume on the stereo, rather than head phones. So whatever he listened to, I listened to, and I got a diverse education in popular music from my older brother’s musical tastes. (Thanks, Tom!) And blues recordings, lots of blues recordings. When I took up the topic of jazz around 1990 and started to think more systematically about it, I was actually a bit surprised how many of the “classic” records and artists I knew. Not that I’d stopped listening to jazz: during grad school I bought a fair amount of jazz and classical music at a discount record store that I frequented. Back then, the big chains disposed of unsold records at discount stores or in “remainder” bins for a dollar each. I remember buying Keith Jarret, Mahler’s ninth, and King Crimson that way. The most important thing, probably, is that my work caught the eye of Lee B. Brown, who was working on the aesthetics of jazz, and we became regular correspondents and then close friends. Until his death in 2014, he and I engaged in twenty-plus years of conversation, much of it centered on the similarities and differences between jazz and rock music, as well as their overlap. I suspect that, had we not connected, I might not have continued to write about jazz.

But those conversations and our long correspondence were also important in confirming the idea that philosophical hypotheses that have explanatory value for one kind of music don’t always hold water when you think about another kind. It’s not simply that we can’t have a monolithic philosophy of art, but it’s that each of the “arts” turns out to be many arts.

3:16: What does a philosophy of jazz do generally that the many books about the jazz greats won’t be so interested in doing? Is it about mapping out the conceptual territory and seeing what makes jazz like other music, what makes it art and what makes it jazz?

TG: I guess the general question behind this is: what has a philosopher to add to what general non-philosophical writers write about an art form? Why should we heed the philosopher in this terrain? Thanks. This is a variation of a question that a musicologist posed to me at a talk at an American Society for Aesthetics meeting. And the answer, of course, is to wonder why we should heed any philosopher concerning any terrain.

The primary reason is that we attend to subtle conceptual distinctions and their implications for our standing assumptions about any topic. There is no end of music writing, some of it published in academic journals and books, that traffics in inherited assumptions and gross generalizations about music and its various genres. In the absence of critical reflection, most thinking and writing about music is overwhelmingly guided by a set of clichés inherited from Romanticism and, to a lesser degree, artistic modernism. The result, too often, is reinforcement of the idea that these clichés hold for all music, or of the other extreme of thinking that a genre such a jazz or heavy metal or bluegrass must be sui generis. My work in the history of aesthetics has made me aware that philosophers have been the source of many of the ideas that have become damaging clichés, so I see nothing puzzling about trying, as a philosopher, to sort out where we’ve collectively gone wrong. To pursue your metaphor about terrain, we’ve helped to create and spread a set of dubious mapping tools, and we need to re-examine them, especially in light of the fact that the terrain itself keeps shifting.

3:16: So is it possible to give a unified definition of jazz given the historical discontinuities it contains? Can you sketch for us the difficulties in doing so and if your definitional strategy works give us the definition you’d be happy to endorse and why?

TG: This problem is parallel to the familiar problem of constructing a unified definition of art given its historical discontinuities. The history of that problem informed my recent attempt to provide a definition, in the book Jazz and the Philosophy of Art (Routledge, 2018), co-authored with Lee Brown and David Goldblatt. Let me say a bit about that book and how it came about. Lee had been working for several years to assemble a set of his essays on jazz into a monograph that would stand as his definitive word on the topic, and he and I talked and corresponded about it while he worked on it. When he became ill and then passed away before he could complete the book, David and I were invited to look at the manuscript and see if we could bring it fruition. We looked over what he’d been doing, which included alternative arrangements of chapters, and we took account of his plan to alter his past work in light of his more recent thoughts and in response to more recent developments. We could see that he’d over-hauled and polished some chapters, but had only fragments toward some others. For the chapter on defining jazz, we started from his own writings and revisions and then we proposed a definition that, we felt, reflected our conversations with Lee on this topic over the years.

Many philosophers now agree that the key to a definition of art or any of the specific arts is to regard cultural achievements as historical developments of specific cultures and to proceed accordingly. In the wake of Paul Oskar Kristeller’s 1951 article on the formation of the “modern” system of the arts, a number of philosophers—most notably Peter Kivy, Denis Dutton, Lydia Goehr, and Stephen Davies—have explored the idea that Western music’s status as fine art—think here of Beethoven and Wagner—is an offshoot of a long history of music as it developed in one small part of the planet. Once you see it that way, it opens the door to the possibility that most music is more like jazz than the ninth symphony or the Ring cycle.

So a good definition of jazz, or of country music, or heavy metal, or any other genre, is going to be complex: it should take account of what all music has in common, really thinking non-prejudicially about all music, while also treating that genre as having both continuities with and divergences from earlier music. We can debate the details, including details about which musical elements are standard and non-standard for the genre we’re defining, but a definition of any art or music genre should pursue that strategy.

3:16: You see jazz very much in relation to historical social developments, and in particular in relation to issues of race and gender, and America. Can you say something about these issues and what you think are the most salient aspects of this dimension of understanding jazz.

TG: Yes, once you start to see the arts and their boundaries as historical developments, it invites you to think more about their social dimension. With jazz, it’s not enough to say that it’s based on improvisation. You have to acknowledge that it arose as, and remains closely identified with, African-American music. This is something that Lee Brown was also very concerned with, and which he and I often discussed. I should also give a shout out to Kathleen Higgins here: I came to think much more about this both from her books and thanks to a critique of my early work at a session of the American Society for Aesthetics. And Paul C. Taylor’s published exchange with Joel Rudinow on race and blues music moved me forward, too.

Philosophically, once you’ve made the move toward a historically-aware, contextualist understanding of both aesthetic judgment and artistic value, it’s a short step to the idea that any and all aspects of the social context of production and reception might be relevant to the music’s characteristics and value. (I stress “might be” here: any and all might be, but in any given case only some will be.) Given my broader interest in how popular music differs from the Western art music, it was only natural to want to think about how American popular music might differ from Bach, Beethoven, and Schoenberg because its form and associated practices of use originated in the music of the African diaspora and as the music of Black Americans.

3:16: Interestingly, you think the notion of the Nietzschean Dionysian festival useful in understanding jazz don’t you? Can you explain the thinking here?

TG: This point isn’t by any means original to me, and, unfortunately, it sometimes appears in music criticism in support of ugly stereotypes about primitivism, which I reject. And not all jazz is Dionysian: think of Miles Davis and “The Birth of the Cool.”

The important Dionysian aspect of jazz lies in its roots in the music of African-American religious ceremonies, and the way that the music was part of a communal, celebratory practice. It wasn’t concert music or music made to entertain an audience. Like many musics, it was functional and participatory, and one of its functions was to bind the group together in an emotional bond. And we see this carried forward in the tradition of the jazz funeral processions of New Orleans, and then the spirit of it also enters the dance halls that were an important incubator of jazz. So there’s a social tradition here that is very different from the one that informs the “fine art” tradition that has such a grip on most thinking about art and music, and so thinking about how jazz is special helps to loosen the grip that the fine art model has on us.

3:16: How important is the interface between jazz and white minstrelsy, blackface, and appropriation in understanding jazz, and wouldn’t someone like Adorno see the appropriation negatively, in terms of deceptive advertising , standardization and predictability – a corrosive tool of social conformity and class exploitation?

TG: This question brings together multiple topics, including ones that I addressed in my first article on popular music, on Adorno’s critique of popular music, and in my second book, I Wanna Be Me: Rock Music and the Politics of Identity (2001), which explores the topic of musical appropriation. Adorno’s concerns about the development of a commercial “culture industry” led him to think that the Black elements of jazz and popular music are there because they’ve been appropriated or co-opted by the industry for marketing purposes. The seemingly-important musical difference between, say, Louis Armstrong and Thelonious Monk are really no more significant than the introduction of colored sparkles into a commercial powdered detergent in order to be able to market it as new and improved. From this perspective, appropriation is basically the ransacking of another culture in order to create meaningless differentiation that drives new consumption. This is not the space to grapple with this whole issue, other than to say that Adorno’s position had an important influence on some sectors of the academic literature and, even more so, on both jazz and rock criticism. It therefore merits examination even if one wouldn’t otherwise think about the Frankfurt School’s philosophy of culture and art.

Personally, I don’t think the “standardization” of popular forms has been quite as sweeping as Adorno claims. Jazz and blues and the some of the more improvisatory rock bands (the Allman Brothers Band, King Crimson) are important counterexamples, either as bastions of oppositional identity or as musical resistance to simple, repetitive musical forms. I argue in I Wanna Be Me that many concerns about appropriation are overblown or poorly thought through. Yet there is a genuine problem with it, both because it so often results in cultural caricatures, and because it deprives subcultures of an important means of cultural differentiation. The minstrelsy issue, much studied now in the field of cultural studies, is just one aspect of the larger issue of appropriation.

3:16: Are there similar issues of the politics of identity and appropriation raised by rock music? I recall reading Dylan writing about that it was when rock split open into pop and soul music that popular music became racialised in a way it wasn’t initially – is the politics more subtle than we might initially think?

TG: Here, again, we find the value of thinking historically. The relevant distinctions started to appear much earlier than that, with the marketing distinction between “hillbilly” and “race” records. Dylan is referring to a later redrawing of genre boundaries, but the phenomenon wasn’t new. And here we find something that Adorno got right: many of the genre categories that we might consider to be self-evident were consciously created by record companies as marketing categories for recorded music. In a segregated America, marketing was attuned to racial politics, and in turn that marketing solidified racial stereotypes and divisions. Which, ironically, hides the reality of constant appropriation across all the various genre boundaries.

And I’d suggest that what Dylan said may be an example of his tendency to knowingly play fast and loose with the facts. He tends to be a playful, untrustworthy narrator. I was recently listening again to his debut album, recorded in 1961, and Dylan constantly foregrounds his violations of the genre expectations of the early 1960s and, in several spots, he associates the “folk” movement with musical appropriation by both commercial interests and by white intellectuals. It’s apparent in his reference to encountering an old blues song in “the green pastures of the Harvard University,” but that’s just one of several such ironical jabs on that album.

3:16: Returning to jazz - If I think about anything as key to jazz it’s improvisation. So what is improvisation for the philosopher of jazz? Why reject Nelson Goodman’s autographic vs allographic art distinction here (you might need to explain briefly what the distinction is about!!!!), and are people listening to jazz impro recordings again and again misguided and irrational given that each time they listen the recording remains unchanged – kind of cancelling out the impro? (As an aside, someone like Dylan improvises and so perhaps similar thoughts occur about how to appreciate him?)

TG: The issue, in compressed form, is that either we need to stop thinking that all musical works are ontologically of one kind, or we have to think of many improvisations as performances of inferior, sloppy compositions, or we have to say that, when musicians improvise, the music has no distinct identity other than occurring at that time and place. I favor the first of these choices, which requires a rethinking of Goodman’s classification scheme.

So I did not set out to reject Goodman’s basic distinction, but rather to show that its application to music doesn’t map out neatly in the way he—and so many others—thought it did. So what is that distinction? An autographic work is one whose identity is tied to the identity of its creator, and so (by misrepresenting who created it), it is also subject to forgery. But some artworks, autographic ones, take their identity from their form and nothing more, and the artist who “creates” them is simply the person who first makes us aware of that particular form or structure. For Goodman, music is an allographic art: any sequence of musical sound is an instance of a specific musical work if and only if it is score compliant for that work (which, for Goodman, includes the score that a non-scored work would have within the culture’s notation system).

And so for Goodman music is not autographic, because it doesn’t matter who composed the work: any sonic event that happens to produce a sound-sequence that matches “Three Blind Mice” simply is an instance of the song. This reduction of identity to formal identity was under a lot of scrutiny when I was getting serious about philosophy of music, but I took a rather different direction from others. As a record collector, it struck me that Goodman’s approach neglects the degree to which music’s form and sonic profile is shaped—both constrained and facilitated—by the technology employed to produce sounds. (There is a possible exception with some a cappella singing.) Now add the familiar point that our notational system doesn’t always do a good job at capturing the music as knowledgeable musicians think of it and perform it: go and look at early attempts to fit African-American music into Western staff notation in the nineteenth century, and then the condescending commentary about the music that results when whites realize that they cannot really notate blue notes and blues techniques.

So, influenced by thinking about the aesthetic differences between silent films and talkies, and between black and white films and the gradual introduction of different color technologies to movies, I pointed out that many of the important aesthetic features of twentieth-century popular music depend on the recording technologies and, in many influential cases, experimentation with those technologies. If you’re a jazz buff, you know that Coltrane’s A Love Supreme record is great, in part, because it was recorded by Rudy Van Gelder in his state-of-the-art studio. And early Elvis Presley records are great, in part, because they used artificial (machine-produced) echo to shape the sound of his vocal delivery. But the moment we start to think about the contribution of the record production of Van Gelder and Sam Philips (or the Chess Brothers, recording the great blues artists of the 1950s and ‘60s), we have to be dealing with an autographic art form, not an allographic art form. And that is because we’re focusing on sonic elements that are not subject to notation.

So, really, when we admire Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, an informed response requires the listener to appreciate two musical works: the composition and the recording. But then why not three, Cotrane’s composition, the quartet’s performance, and the recording? And then what is the recording a recording of, if essential parts of the music aren’t things that can appear in notation, and the recording is itself spliced together from multiple performances?

Conversely, Goodman’s idea that music is always allographic implies that every original improvisation reveals a new musical work. In principle (and in practice, in music schools!) improvisations can be notated and then performed again by someone else who follows the score, and for Goodman they will be playing that same music. But if you think that part of the point of improvisation is that it’s supposed to be a one-off event, not subject to replication or repetition, then improvisations look to be autographic musical works, too, in the same way that Michelangelo’s David statue is an autographic work. So it looks as if there are two kinds music that call should be regarded as autographic art in a warranted, appreciative response. There is musical improvisations, but there is also recorded music where the recording technology contributes additional, musically relevant sonic properties. Thinking through all of this, Lee Brown and I got into extended discussion about what’s going on with something like Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert of 1975, where there was an autographic piece (a fully improvised performance) made available to us thanks to a different autographic work (the album). Lee Brown and I went back and forth on the question of whether our ability to listen to an improvisation a second time was aesthetically irresponsible and harmful to our listening habits, as a falsification of the inherent one-time-and-its-gone ephemerality of improvisation.

For me, the question is a more general one: if music is a performing art, isn’t every recording a distortion of the audience’s proper relationship to the music? And there are two lines of response, both of which I’ve explored. First, we can and should recognize that distinct sets of aesthetic and artistic standards apply to a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, on stage, and a film version, such as Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 film. We can, and should, attend to the distinctive processes of creation in the two cases—their artistry—while allowing that knowledgeable audiences can appreciate those processes without being able to observe directly many of the steps that went into its creation and presentation. (David Davies has important things to say on this topic.) Mutatis mutandis, the same holds for recorded improvisations, provided the listener understand its status as improvisation. So listening to a recorded improvisation is no more irrational than viewing one of Jackson Pollack’s drip paintings.

3:16: .Are jazz improvisations flawed even if judged against appropriate standards (not against Eurocentric standards!)

TG: They are not necessarily flawed, but they are frequently flawed. And this is a basically matter of artistic goals. Jazz musicians are the first to admit that many of their improvisations are flawed in relation to some of their goals. Granted, there are some famous jazz improvisations (e.g., by Sonny Rollins) that are jewels of musical design. But a standard goal of much improvisation is real-time exploration of a musical motif or framework or set of “changes,” and the jazz tradition also values risk-taking in improvisation. Risks often fail, and exploration leads musicians into dead-ends or, pursuing that metaphor, stretches of being trapped in a roundabout while thinking about which direction to take upon exiting. And no ensemble wants a member who plays “clams” (notes that don’t fit in). While the ability to adapt and recover from slips and clams is a positive value when improvising, there are all too many occasions when a bum note or ill-timed entrance is simply a flaw. Or two members of the ensemble might be poorly matched as partners for musical interplay, as when Cannonball Adderley felt that Bill Evans didn’t support him aggressively enough and wanted Miles Davis to remove Evans from the group.

So, even if you shake off the expectation that the music’s formal design will be as “logically” organized as a movement by Haydn or Beethoven (and here I’ve consciously used a term that’s frequently invoked to explain how classical composition is different and purportedly superior), improvisation generally seeks a combination of “flow” and some degree of novelty. Yet these features may be absent from the performance at crucial moments or even for the duration of the improvisation. There’s a good reason there are so many outtakes when they make jazz recordings! And of course this isn’t just jazz. There are improvisations by the rock trio Cream that stumble or become tedious, and Grateful Dead jams aren’t all gems.

3:16: I think following your detailed thinking about this one particular field of music helps us see some general approaches you take as a philosopher of art and music. You’ve written extensively about the philosophy of music, and in one of your books you quote approvingly Nietzsche saying that without music life would be meaningless and Wittgenstein that philosophy is about assembling reminders for a particular purpose. Could you say something about your general approach to art and to music in particular, and why you argue that all music is art which might strike some of us as being a bit of a stretch?

TG: Why is someone singing a lullaby art, for example? The difference between Miles Davies and the lullaby singer seems more than cultural status. I won’t belabor this one, but I’m part of a larger movement within philosophy of art that has been trying to shake off the assumption that art exists solely to give us complex and rewarding aesthetic experiences when the artwork is appreciated by a disinterested observer.

That’s what some art became, yes, and that’s also true of a number of musical traditions other than Western classical music. But this cultural development shouldn’t obscure the fact that the arts didn’t’ start that way, nor do we want to adopt the view that it was somehow unfortunate that none of the church-goers who were the original audience for J.S. Bach’s religious cantatas were able to regard them disinterestedly, as fine art. Following Ellen Dissanayake and Stephen Davies and a range of other authors, we want to think more about the arts in early human societies, when art was always functional—generally either decorative or ceremonial—and not, as is often said of fine art, autonomous.

Music is the great mystery here: it obviously didn’t start out as concert performances, nor as entertainment, so why did it develop? What was the evolutionary advantage of being a musical species? And the best answer seems to be its value in generating group cohesion and, perhaps, empathy, and from this perspective lullabies look to be closer to the essence of music than a Beethoven piano sonata. This is also why Jazz and the Philosophy of Art begins with the question of the social settings and functions of early jazz and its immediate precursors. Jazz didn’t start out as concert music for a seated, attentive audience. Miles Davis arrives after decades of development, at the point when jazz begins to function more like fine art than entertainment for the masses.

But being entertainment, or being functional in some other way, doesn’t disqualify music from its status as an art. And we should always remind ourselves how recently we’ve arrived at the general idea of autonomous fine art: throughout the formative period of the eighteenth century, many philosophers still regarded the arts as forms of entertainment. Have a look at Joseph Addison, and look again at Hume’s famous essay on the standard of taste.

3:16: Do ideas imposed on art – like Shopenhauer saying music provides spiritual insight - interfere with aesthetic responses, and if they do, is this a bad thing? And when you argue that sublimity is a neglected vehicle for spiritual insight through music why isn’t that just the same idea but dressed up more?

TG: I like that! I wouldn’t deny that some of my work on the sublime is Schopenhauer dressed up a bit. The big difference is that Schopenhauer argues that that’s music’s distinctive essence, and I see it as just one thing that music can accomplish. To repeat a point I’ve made in several places, a simple love song or a Chopin waltz can be aesthetically good without aiming to give us spiritual insight, and a lot of music is good because it’s good as dance music, some of which facilitates the kinds of trance states that are associated with spiritual insight, and some of which is just for fun, or for other social purposes, such as the “first dance” at a wedding reception.

But you’ve brought up something very important. We have aesthetic experiences in all kinds of situations where there aren’t any big ideas at work. But art also develops—and it does so in every society, apparently—as a vehicle for ideas. Botticelli’s La Primavera is a ravishing painting, and the ideas it encodes are complex and subtle. There’s ongoing debate about the degree to which it’s infused with Renaissance Platonism. And its grouping of mythical figures, and their poses, doesn’t have any counterpart in any known story or myth—so why did the artist choose this grouping? Now we’re in the realm of ideas, and, frankly, some of the ideas illustrated there are profoundly unattractive. That’s a sexual assault over there on the right, and the painting apparently endorses it. Once you grasp that, the ideas and values that inform the painting can interfere with our aesthetic response. At the same time, given its complexity, other ideas that are in play may guide and thus enhance our aesthetic response, as with the array of flowers that are shown, and the figure of Mercury on the far left.

3:16: You’re interested in more than music of course – you range over a whole bundle of arts and are keen to point out that its not a unified field but each art raises particular questions of their own many of which can’t be generalized. But you do discuss contextualism and this seems to be a position you’re interested in and seem to endorse. Could you say what you take to be the interesting claims of contextualism in the context of art and aesthetics, what are the rival positions and why you take it to be superior to those?

TG: I just gave an example—the Botticelli—that illustrates this. If we don’t explore the cultural expectations that inform past art, our responses remain superficial. Granted, many responses to great art are superficial. I once spent an hour sitting and looking at Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, and confirmed something I’d read, which is that the average museum-goer spends 30 seconds or less looking at any work on display. And it seems to be getting worse, as many people pause only as long as it takes to take a “selfie” with their phone. But most artworks are culturally significant as well as aesthetically interesting: the superficial or immediate aesthetic response is a crumb of what much art has to offer. But that is because the context of production enters into the properties that are embodied in the art, and that context ought to be taken into account by appreciative observers.

That much is probably obvious to most readers of this interview. La Primavera has a message about sex and love filtered through Platonism, and A Bar at the Folies-Bergère is also freighted with issues of gender and sex, but also class relationships, and also self-reflection on cultural practices related to artistic representation and art viewing. The thing that is less obvious, and which I emphasize in a lot of my work, is that our aesthetic response is to art is guided by all of that cultural freight. As Kendall Walton famously observed, Beethoven’s piano sonatas are pieces of tuned percussion, and they contain lyrical passages only relative to other piano pieces, and listeners must learn to approach them in relation to an appropriate comparison class. Within our own culture, and especially with popular art, we acquire the relevant background knowledge without effort, and so the contextual dependency of our aesthetic response is largely invisible.

So the most important point here is that there may occasions where aesthetic response is disinterested and “pure,” of the kind described in Kant’s “Critique of Aesthetic Judgment” within the third Critique, but it’s not the normal, nor proper, appreciative stance for most art. Nor with most of nature, either! A baby hearing a lullaby might be having a pure, disinterested response, but if that’s how you approach Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge (Op. 133), the music is just horrible and ugly and frequently boring. Its positive aesthetic dimension requires some sense of where it falls in the history of Western music, and hearing it in relation to an appropriate comparison class. And this has, perhaps, been my larger goal ever since writing a doctoral dissertation on Kant’s third Critique and understanding how a theory of pure aesthetic response differs from a theory of art appreciation: we want to avoid a narrow formalism, we want to avoid the excessive prioritization of direct perception—a prioritization that’s come to be known as aesthetic empiricism—and we want to avoid the arrogance of thinking we can aesthetically evaluate the products of any culture but our own prior to gaining a sympathetic engagement with its values, history, and practices.

3:16: I mentioned the arts and aesthetics in the same breath in that last question and yet they’re coming apart these days aren’t they and aesthetics is being treated as having its own set of philosophical issues discrete from art. Can you tell us what are the important distinctions now being made between art and aesthetics and what questions you’d expect to be on the agenda for a philosophy of aesthetics that would exclude art?

TG: This is exactly right, and it is something that is frequently overlooked about the field as it’s been developing over the past sixty years. Without going into detail, I’ll start by making the well-known point that the development of minimalism and conceptual art challenged the assumption that art’s essence lies in its aesthetic dimension. Famously, Arthur Danto pointed to a specific encounter with pop art as the moment he understood that artistic value and beauty had become divorced, opening the door to a philosophy of art that wasn’t focused on aesthetic judgment or aesthetic value.

About the same time, environmental degradation led to more attention to environmental aesthetics, and so we got a second divergence of aesthetic theory from philosophy of art, but coming at it from another direction. We also have the relevance of a long tradition of aesthetics and mathematics, and a growing interest in the aesthetics of sports. But neither a football match nor a mathematical theorem nor (my own example in a forthcoming paper) a view of a stretch of the Mississippi river are works of art. Finally, there’s been a growing interest in what’s known as everyday aesthetics. It’s hard to think of an exception to the principle that human design reflects aesthetic preferences. Why, I have to ask, did my parents want to live with avocado green appliances?

Aesthetic judgment permeates our human world, and we have an endless number of types of things that invite philosophical reflection without ever talking about art. In short, we might do a better job of understanding the nature of aesthetic value and the complexity of our aesthetic vocabulary by ignoring art, because the topic of art brings in all the cultural complications that I talked about in response to your last question. And if you think that there’s a connection between aesthetic value and knowledge, or you think some aesthetic responses involve spiritual insight, the aesthetics of nature might get us to the heart of the issues more rapidly by decoupling it from philosophy of art.

3:16: You approach your philosophical insights as an analytic philosopher – do so-called continentals do things differently from you? (I’m skipping over the issue of what we mean by continental philosophy but you may wish to say what you mean!)

TG: As I noted, I was trained to be “Continental” (post-Kantian European philosophy) before I was trained to be analytic. I only started to study Kant and the 20th century Anglo-American tradition during my first year of graduate work. I recall one of my professors being unhappy that I’d arrived without ever having been exposed to Descartes. But I quickly gravitated to the study of Kant and analytic philosophy as my primary focus. To the extent that my work stresses conceptual analysis and examines nuances of language use as a reflection of concepts, judgments, and logical connections, my work reflects the analytic tradition.

But to confine ourselves to that tradition is to ignore a lot of interesting work in aesthetics and philosophy of music, including Nietzsche, Adorno, Roman Ingarden, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Attali. I tend to shy away from the sweeping cultural critiques we find in many of these authors, and I’ve been criticized for cherry-picking them—borrowing an idea here, and idea there. But there are also readers who’ve thanked me for making some of their writings on music more accessible.

3:16: And finally, are there five books you could recommend to the readers here at 3:16 (apart from your own) that will take us further into your philosophical world?

TG:

Theodor Adorno, Essays on Music, edited by Richard Leppert. University of California Press, 2002.

Stephen Davies, Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Ellen Dissanayake, What is Art For? University of Washington Press, 1988.

Kathleen Marie Higgins, The Music of Our Lives. Revised edition, Lexington Books, 2011.

Peter Kivy, Philosophies of Arts: An Essay in Differences. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

NEW: Joseph Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised