Thinking About Climate Change, Global Justice and Trans

Interview by Richard Marshall.

(Art by Mickalene Thomas)

‘I think if we actually established that we cannot solve climate change and nothing we can do will make things any better for its victims, then yeah, we should stop trying. ‘

‘And won’t is not the same thing as can’t, particularly because can’t gets people off the moral hook in a way that won’t just doesn’t.’

‘I feel like there’s quite a bit of resistance to the idea of collective punishment in the popular imagination, partly because of practices in some parts of the world like punishing brothers for what sisters do, or punishing national minorities for what some extremist members do. And perhaps also because of films like Jimmy McGovern’s Common, which show the way that there can be miscarriages of justice under joint enterprise laws.’

‘I draw a clear line between the kinds of groups that count as collective agents and the kinds of groups that don’t. Groups like consumers, the affluent, men, or white people, don’t count as collective agents, because they’re not internally organized, so they’re not candidates for collective responsibility. That means we have to tell a different story about responsibility for global labour injustice (poverty, sexism, racism). ‘

‘Some people defend geoengineering as a last resort, so they say we couldn’t do it now while we still have other options (like directly reducing GHGs), but we could perhaps do it when our only choice is between that and facing the harms of climate change unabated. But this is a risky argument to make, because it might lead to people waiting until it’s too late so that they can claim they’re only doing the best thing in the circumstances. ‘

‘I’ve been surprised by the levels of vitriol that have been directed at me and other radical and gender critical feminists within the profession. My stance is that a person can’t change sex (not even with sex reassignment surgery), that ‘gender identity’ has no bearing on sex, and that with very few exceptions gender identity should have no bearing on a person’s sex-based rights. Complications arise because of the extreme heterogeneity within the group of transwomen, from fully passing transwomen who have had sex reassignment surgery, to male-appearing transwomen (sometimes to the point of having full beards) who don’t take hormones.’

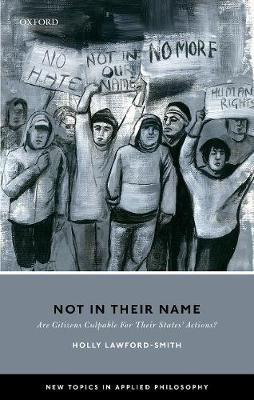

Holly Lawford-Smith is a New Zealander living in Melbourne, Australia interested in radical and gender critical feminism, and their perspective on questions about sex, gender, and gender identity; and the ethical and political questions arising from proposed legal changes to trans people’s and women’s rights, including theoretical questions about collective action, collective agency, collective responsibility, and collective punishment. Here she discusses climate change, the crimes done by collectives, the law and joint enterprise, global justice, whether climate change matters all-things-considered even if it matters pro tanto, defences of the idea of morally objectionable class-based advantage, the obligations that come with class, race and sex privilege, and the toxic debate around transgender.

3:AM: What made you become a philosopher?

Holly Lawford-Smith: I didn’t really have an conception of what a philosopher was when I started university, but I signed up to a class in ethics that looked really interesting, and from there I was hooked! Always taking existential angst home and annoying my flatmates. I did a mixture of stuff – Philosophy of Science, Kant, Political Philosophy, History of Philosophy, Ethics. I can’t remember any class that I didn’t like. From there I guess you kind of get on the conveyer belt—a lecturer encourages you to do Honours, an Honours supervisor encourages you to do a Masters… and there you go. I took a couple of days off work last year to go to a printmaking class, and we had to introduce ourselves at the start, and people were saying their names and occupations, and I said ‘hi, I’m Holly and I’m a philosopher’. And there was this awkward pause, and then a lady said very kindly, “well… I guess we’re all philosophers in a way”. That cracked me up. I didn’t correct her.

3:AM: You’re engaged with some of the most urgent questions of our day, particularly issues relating to climate change, global justice and so forth. You think ‘ought implies can’ – but if we worked out that these existential threats were just too hard for us to solve would you say that we should relax and stop trying? I guess I’m wondering whether the ‘can’ in the can/ought issue is one that can always be doubted or finessed so that ought survives, and if it is, we can always impose the normative obligation?

HLS: I think if we actually established that we cannot solve climate change and nothing we can do will make things any better for its victims, then yeah, we should stop trying. That’s because resources are scarce—like the money and energy that goes into activism on this issue, and the investments the government might make into infrastructure aimed at tackling it, and so on. But I don’t think it’s true that we can’t solve climate change. I guess I tend to approach ‘can’/’cannot’ via the idea of ‘infeasibility’, and the way I like to think about in/feasibility is in terms of conditional probability. So when we want to know if Australia could make a difference to the negative impacts of climate change, or global poverty, we ask, what is the chance of Australia’s making a difference, given that it tries? Then of course there are questions to ask about who the ‘it’ is (I think it’s best understood as an organized group comprised of the government and wider public service), and what exactly it means for them to try (probably for them to make climate action a central issue, to channel resources into it, to work to bring the public on board with supporting it, etc.), but in general I think one thing this brings out is that often our judgements that we can’t do something are actually being driven by the thought that we won’t try to do it. And won’tis not the same thing as can’t, particularly because can’tgets people off the moral hook in a way that won’tjust doesn’t.

3:AM: Many crimes are done by collectives – corporate leaders in the big corporations and businesses – and government state departments. Should there be collective punishments for these, and what kind of punishments could these be, and how would they be distributed across the group?

HLS: I have to clarify a thing first! That is, that you’re already suggesting a story about punishment and distribution when you move from ‘collectives’ to ‘corporate leaders’. The first thing to notice is just that collectives like corporations, churches, and states cause harms, and sometimes they do that in a way that follows from their collective intentions (there’s a separate debate about how exactly to understand these) and in a way that they are not excused from. Then there’s an interesting question, which is, how do we think about what the collective is such that we can assign collective responsibility to it? Different theories of groups and different accounts of membership will give different answers to that. You suggested one account, which is that corporations and businesses are their leaders. We could say the same thing about the state – Australia is Scott Morrison, or the Executive. I like a view of corporations that counts all employees as members (but excludes shareholders). I think there should be collective punishment where there’s been crime for which there’s collective responsibility, and I think the punishment will have to take certain forms to accommodate the plural nature of the collective (e.g. jail time probably won’t work). The punishment should be distributed across members in proportion to their position in the corporate hierarchy, so that people higher up in the management get more, and people lower down like entry-level employees get less, but everyone gets some.

3:AM: Is there a different kind of collective responsibility on states than for the big corporations and businesses?

HLS: Well, the main difference is in how we think about membership in each. I just said above that when it comes to corporations I like a view that counts all employees. That fits reasonably well with ordinary intuitions about who’s a part of the corporation. But when it comes to the state, ordinary intuitions will tell us that the people are part of the state, if not the whole story about what the state is. One prominent way of thinking about what the state is conceives of it as the people governing themselves through elected representatives. But I argue in my book that if we understand the state as including the people then we can’t make sense of it as a collective agent, and so we can’t think it has collective responsibility for its actions. We should want collective responsibility, if we can get it, so that’s a reason to go with a narrower understanding of membership in the state. I think that’ll be something like the elected officials and wider public service. But apart from those questions about membership, yeah, I think corporations and states are fairly similar in that they are large and complex collective agents that bear collective responsibility for the harm they cause intentionally.

3;AM: And what’s the relationship between your views and the law of joint enterprise?

HLS: I’ve been thinking about joint enterprise quite a bit lately in connection with this question about collective punishment. I feel like there’s quite a bit of resistance to the idea of collective punishment in the popular imagination, partly because of practices in some parts of the world like punishing brothers for what sisters do, or punishing national minorities for what some extremist members do. And perhaps also because of films like Jimmy McGovern’s Common, which show the way that there can be miscarriages of justice under joint enterprise laws. This is a law that allows all contributors to group crimes to be punished for the full extent of the crime. So say for example that four gang members beat someone to death, but one was just doing some light kicks or some cheering on from the sidelines, while another one was really laying in and doing the bulk of the attack. You could still send both of them to jail for murder, if certain conditions were met. I’d been puzzled by whether this is a case of collective punishment or not, because on the one hand it does take seriously that no matter the contingent causal contributions to the crime that an individual member makes, they were a part of the crime, and deserve a share in the punishment for it. But on the other hand, it’s not like the group is getting a punishment for murder, and this is being distributed between the contributors. Rather, they’re each getting a punishment for murder. I think if we really took the idea of collective agency and collective responsibility seriously, this would look like overkill in terms of punishment. So I think probably the current way we implement joint enterprise law isn’t actually an example of collective punishment, even though there are other ways we could implement something like it that would be.

3:AM: You ask some great questions so I thought I’d ask you to sketch for us the way you tackle them: so do you think purchasing makes consumers complicit in global labour injustice?

HLS: In the way I think about collective responsibility I draw a clear line between the kinds of groups that count as collective agents and the kinds of groups that don’t. Groups like consumers, the affluent, men, or white people, don’t count as collective agents, because they’re not internally organized, so they’re not candidates for collective responsibility. That means we have to tell a different story about responsibility for global labour injustice (poverty, sexism, racism). One way to do that is by thinking about individual complicity in global labour injustice, which means identifying the perpetrators of it, and then thinking about the relationship that individuals stand in to those perpetrators’ actions. Corporations are good candidates for being perpetrators of global labour injustice. In the paper where I talk about this issue, I use Chiara Lepora and Robert Goodin’s framework for thinking about complicity, and work through whether consumers fit the distinctions they make. I argue that they seem to fit a few of them, so indeed we can say that consumers are complicit in global labour injustice. Consumers may condonethe original injustice involved in the creation of the products they buy, by buying them; they may connive in future injustice, by creating demand for further products whose creation will involve injustice; and they may be complicit simpliciter (a technical notion for Lepora & Goodin) because their purchases come with an expectation of advancing the interests of the corporations whose production practices involve injustice (e.g. by contributing to their profitability).

3:AM: Many of us are carbon emitters and cause environmental harm because of that yet you say we aren’t agents and so are not culpable for the harms. Am I right that this is your position and how come we’re not culpable and yet engineers deploying stratospheric aerosol injection are?

HLS: Here it depends what you have in mind when you say many of us are carbon emitters and cause environmental harm. If you mean, many of us taken together as a group, then it’s certainly true that we cause environmental harm. If you mean, many of us taken as individuals, then it’s not true that we cause environmental harm—at least, not with every emission, and perhaps not with any emission. For the same reasons I just outlined in talking about ‘consumers’ as a group, ‘carbon emitters’ are not the kind of group that counts as a collective agent, and so they can’t be responsible as a groupfor the climate harms they cause. The comparison between carbon emitters and engineers deploying stratospheric aerosol injections (SAI)—a form of geoengineering that involves interventions aimed at reducing temperature rather than reducing the emissions that cause a rise in temperature—came up in response to an article of Christopher Preston’s.

He argued that deployers of SAI and carbon emitters have parallel responsibility, and that this is surprising, because intuitively carbon emitters have little responsibility and deployers of SAI have a lot of responsibility. He made the case for that by appealing to the doctrine of double effect, where we give lesser responsibility to bad outcomes that are unintended, and come about as the result of trying to secure good ends. But his argument rested on some ambiguity about who the agents of emissions are. I argued that once we resolve that ambiguity, the parallel responsibility claim collapses, because we’re either comparing agents with non-agents (who therefore can’t have parallel responsibility, because one has no responsibility at all), or we’re comparing agents, but one doesn’t cause environmental harms, so their responsibility can’t be parallel.

3:AM: When discussing this issue of the ethical obligations on private citizens in relation to some arguments from John Broome you ask whether climate change matters all-things-considered even if it matters pro tanto? What do you conclude and can you sketch why?

HLS: I got really interested in this question of pro tanto vs. all-things-considered obligations when I noticed during my PhD how many people at conferences would make claims about moral obligations and then state during question time that these claims were only pro tanto. There are sooooo many claims about obligation being made across moral and political philosophy! It’s like… we have obligations to do with poverty, and climate change, and misogyny, and racism, and unfair trade, and immigration, and gentrification, and treatment of non-human animals, and… yeah. But no one really seems to be asking about what we actually ought to do, taking everything into account, and given that we just can’t do everything. Climate change is a good candidate for being the most serious moral harm we’re facing today, in terms of scale and severity, or it’s at least neck-and-neck with global poverty (not to mention interconnected with it).

So in a discussion about John Broome’s book Climate Matters I asked whether individuals’ climate-related obligations are merelypro tanto, or also all-things-considered. That is to say, do climate obligations make it to the top of the pile of all the obligations we have? In trying to answer this question I suggested that incommensurability, reasonable disagreement, and differences in people’s sympathies, may all undermine the case for there being any strict hierarchy of injustices (and we’d need to be able to build the hierarchy to find out whether climate change was at the top of it). So I disagreed with Broome that we have an all-things-considered duty of justice to offset our individual GHGs to zero, and said that the only person who’s clearly violating her duties of justice is the person who is doing nothing at all—or not enough—about at least one of the injustices she is implicated in.

3:AM: Some people have proposed quite radical solutions to the climate change challenge such as enhanced weathering (you might have to sketch what this is for the readers not familiar with the term) and among other things this raises the ‘dirty hands’ issue – we do a bad thing to offset something even worse. Is this ethical and what does this dilemma reveal about the interaction between ethics and scientific research and technological fixes?

HLS: Yeah—before I left Sheffield I was briefly involved as the ethicist on the Leverhulme Centre for Climate Change Mitigation project, which was focused in Enhanced Rock Weathering. That involves imitating a natural process whereby rock is eroded and then during rainfall the tiny bits of rock absorb carbon, and ultimately end up in the ocean. But you ratchet up the scale of the natural process, so the proposal was a form of geoengineering where you grind up rock dust manually and sprinkle it from helicopters over large tracts of land, and then it can absorb much more carbon during rainfall than it usually would. As with any large scale intervention on the global climate system, there’s heaps of uncertainty around exactly what would happen when you tried to do that, so this project was planning to do controlled tests within certain areas and figure out whether it would work at scale and how much it would cost and stuff like that. But I ended up moving to Australia before things really got going there, so I didn’t end up writing much on this, except for one paper that I wrote together with Adrian Currie, which reviewed the various ethical issues that are relevant.

One is the one you mentioned, about ‘dirty hands’. This term comes from thinking about situations in which you have to choose between two actions, both of which are morally compromised, so that you get your hands dirty no matter what you choose. Some people defend geoengineering as a last resort, so they say we couldn’t do it now while we still have other options (like directly reducing GHGs), but we could perhaps do it when our only choice is between that and facing the harms of climate change unabated. But this is a risky argument to make, because it might lead to people waiting until it’s too late so that they can claim they’re only doing the best thing in the circumstances. And of course, we don’t want that! We want to not end up having to make a choice like that in the first place. I think it’s pretty clear that we should be doing a lot more to reduce emissions, rapidly and drastically, in rich developed countries, instead of taking massive risks with a complex system that might result in catastrophic harms to current and future generations, non-human animals, ecosystems, and the environment more generally.

3:AM: You take a controversial looking ethical position towards class privilege: you defend the idea of morally objectionable class-based advantage. Some argue that the affluent are responsible for global poverty and the injustices that come with that so what’s the case defending this group?

HLS: I started thinking about class, race, and sex-based advantage through my work on benefiting from injustice, and I wanted to write about class because I was living in the UK at the time and it was the most salient axis of oppression where I lived. Discussions of benefiting are usually built around toy cases where one person perpetrates a harm against another, and an innocent third party benefits from the harm. Then sometimes people draw conclusions from these types of cases for benefiting more generally, like that current populations benefit from historical injustices against indigenous peoples. RJ Leland and I have a paper we’re currently working on where we question this generalization. Race, class, and sex-based advantage are all cases where one large, unorganized social groups seems to benefit from the oppression of another large, unorganized social group, e.g. white people benefit from the oppression of people of colour, middle-class people benefit from the oppression of working class and precariat people, male people benefit from the oppression of female people.

In the paper where I discussed this I argued that class privilege is not usually culpable, that is, there’s not usually anything that people in class-advantaged groups do to intentionally cause the disadvantage of the class-disadvantaged. But this doesn’t mean they have no obligations; it just means they don’t have the strongest obligations that come from being culpable. I borrowed from the climate ethics discussion of offsetting emissions to avoid the harm they do in order to fill in some content for the obligations the class-privileged have, suggesting a number of different ways they might offset that privilege. They can’t avoid having it, but they can neutralize its effects with certain kinds of actions. So it’s not quite that I defended the idea of morally objectionable class-based advantage, more that I said it’s not culpable. I didn’t connect this up with global poverty in that paper, I was more interested in the obligations between class groups within one society, like the UK.

3:AM: So to make this advantage non-culpable, what obligations come with class privilege?

HLS: My argument was that the class-privileged need to take on costs in order to undermine the source of class privilege and class-based disadvantage. I understood ‘costs’ in terms of time, effort, money, or other material resources, and gave a non-exhaustive list of ways to do that, including things like challenging classist comments, collectivizing against class injustices, standing in solidarity with organized groups experiencing class-based oppression, encouraging their workplaces to use anonymized CVs in hiring to mitigate class bias, sending their children to public schools, etc. In that paper I also returned briefly to the point mentioned above about whether these obligations are pro tanto or all-things-considered, and said that this depends on settling the debate about the permissibility of partiality towards co-nationals. Because class is one of the the most prominent sources of injustice in the UK, obligations to offset class privilege will be very important, so perhaps rise to being all-things-considered, if we do owe more to co-nationals than outsiders. But because the UK is a rich country and there are more prominent sources of injustice outside it, obligations to offset class privilege are likely to be outweighed by other obligations (like to act against climate change) if we owe as much or more to outsiders.

3;AM: Do the same kinds of obligations come with race privilege too then – or does race present us with a different kind of problem?

HLS: I think all of these ‘big three’ axes of oppression—race, class, and sex—work in pretty much the same way when it comes to privilege. There are interesting differences between the three categories, because sex has a biological basis and is almost always immediately visible, while that’s less true for race and there’s the whole issue of people from one group ‘passing’ as members of another, and then with class there’s no biological basis at all but there are nonetheless certain markers that show up in appearance that can be the basis of certain sorts of treatment, but there’s social mobility through the class ranks in a way that really isn’t true for race and usually isn’t true for sex (although is becoming a little more true with the increasing number of female people transitioning to live as men). But I think once you have privilege from one of these three categories—being white, being middle-class, being male—you have obligations to offset that privilege, and in a way that targets the original source of the fact that you have that privilege in the first place.

3:AM: Transgender has become a rather toxic issue but you have strong arguments about this issue. Where do you stand on this? How do you think we should think about all its complexities, and in particular why is it becoming something where feminists and trans people are falling out when you’d have thought they’d have been allies? Is anti-women sexism a hidden factor in all the rage?

HLS: It really has become toxic! I’ve been surprised by the levels of vitriol that have been directed at me and other radical and gender critical feminists within the profession. My stance is that a person can’t change sex (not even with sex reassignment surgery), that ‘gender identity’ has no bearing on sex, and that with very few exceptions gender identity should have no bearing on a person’s sex-based rights. Complications arise because of the extreme heterogeneity within the group of transwomen, from fully passing transwomen who have had sex reassignment surgery, to male-appearing transwomen (sometimes to the point of having full beards) who don’t take hormones. It seems like we’d want a law about discrimination against women in the workplace to protect the former person, because after all, all of her colleagues may believe her to be female, and so she may be genuinely subject to the same treatment that female people are subject to in that context. But it would be absurd for that law to protect the latter person, who everyone in the workplace will know to be male. Perhaps that person is subject to other kinds of discrimination, like for being trans, or for being gender non-conforming, and we should want laws to protect against that.

But we don’t get that by turning a law about female people into a law about anyone who feels a certain way about themselves no matter other people’s perceptions. My understanding is that radical and gender critical feminists, and trans people and trans allies, are falling out because trans people and trans allies expect feminists to be allies to the trans cause, and those feminists’ emphasis on the male/female distinction feels to trans people like a kind of betrayal. But those feminists also feel enormously betrayed by trans people and their allies, in particular by the trans allies who claim to be defending trans rights but really seem to be mostly interested in just venting all their pent up misogyny onto women, this time with a socially legitimate excuse for doing so! (Because we’re transphobes,you know, so we must deserve it). Just have a look at the kind of pushback women are getting compared to men—in our own profession e.g. Kathleen Stock in the UK compared to Alex Byrne in the US. So yeah, I definitely think there’s sexism hidden behind all the rage! We’re in a profession that is dominated by males—is in fact one of the worst disciplines across the arts for this—and who are people the angriest in at in the profession right now? Women. For excluding males. With their feminist theory. It’s beyond ridiculous.

3:AM: And how do you approach the issue of male violence in this issue, in particular regarding safe spaces?

HLS: I mean, it’s the main reason why radical and gender critical women are so vehemently opposed to sex self-identification passing into law! I mentioned already how much heterogeneity there is within the group of transwomen. Even if we think that sex reassignment surgery or hormone therapy make a difference to the effects of male socialization and thereby to male violence—and there’s no evidence so far that this is true, as far as I’ve been able to find—that still leaves all the transwomen who don’t have either, as part of the group that sex self-identification would give entry to female-only spaces (safe spaces). There is literally nothing about ‘gender identity’, which is nothing but a way a person feels about herself, that could make this kind of difference.

I don’t understand how so many apparently clever people have decided that it could do. So either we need to make some distinctions among the people in that heterogeneous set, say between transsexual women on the one hand and non-transsexual transwomen on the other hand when it comes to female-only spaces, or, we need to treat all the members of that group in the same way, and if we do the latter I think that has to mean waiting for evidence that gender identity alone makes a difference to male socialization and likelihood of committing violence—including sexual violence—against women and girls. And of course while violence is a huge issue, it’s not the only issue. Just as people of colour talk about needing spaces free of white people, you know, to be free of dominance behaviours and the judgements and expectations white people have of them, female people also need spaces free of men for the same kinds of reasons. A transwoman’s having had sex reassignment surgery doesn’t guarantee that the behaviours and attitudes conferred by her male socialization will disappear.

3:AM: And finally, are there five books you can recommend for the readers here at 3:AM that will take us further into your philosophical world?

HLS: I feel like I read philosophy papers so much more than I read philosophy books, I’m not even sure I could think of five I’ve read cover to cover! Is that terrible? How about if I recommend books that relate to philosophy in interesting ways instead.

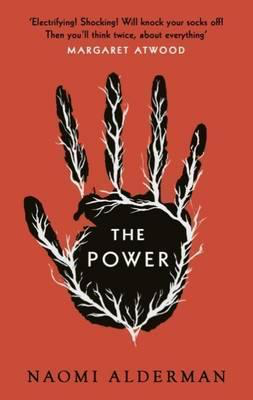

The Power by Naomi Alderman, because is there anything better than a utopian feminist revenge novel?

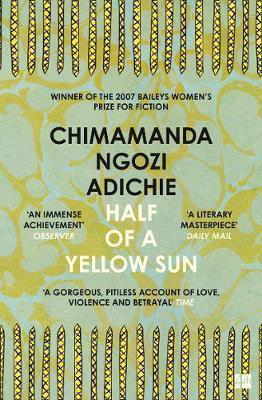

Half of a Yellow Sun, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, because there are great insights about gender and race and war, and also just because she is just such a wonderful writer.

Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin. This white guy figures out a way to pass as African American and goes travelling through the segregated south of the US and talks about what he experienced. Useful for thinking about privilege, and testimony, and how that might relate to being a good ally.

On Mating by Norman Rush, because who would have ever thought it would be possible for a male writer to write a female character like that? Maybe standpoints are only a thing because none of us work hard enough to understand each other.

And finally, the Ender’s Game series by Orson Scott Card, because there’s this painful scene in there about the extreme ways in which people from different groups can misunderstand each other which always stuck with me, but also because I think there’s so much philosophy in sci-fi in general, and because Orson Scott Card was actually the first person to publish my work—he published my Honours Dissertation in full in his magazine The Intergalactic Medicine Show.That was pretty exciting at the time!

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his new book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the first 302