Towards The Quieter Virtues And Other Issues In Philosophy Of Education

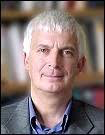

Interview by Richard Marshall

'I argued that there were aspects of knowing that were far more interesting to education in its widest sense of helping young people to develop and flourish than the somewhat desiccated propositional sense that ran through Hirst’s work and that of many of his contemporaries.'

' ... good educational research can often be philosophical rather than empirical. Happiness is a good example. It’s not – as non-philosophers sometimes imagine – that before we can do the real research we have to define happiness, and philosophers can come in handy here before passing things over to psychologists and other specialists. Rather we have to think carefully about what kinds of happiness are educationally desirable – the satisfaction of mastering another language over years of hard work, perhaps, or learning to play a musical instrument well..'

''Management of change cant should be vigorously ridiculed by anybody with the energy, wit and security of employment to do so. This is not a particularly philosophical matter, though Socrates, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and others seem to have thought that philosophers ought to make mockery part of their trade.'

'Aristotle wrote illuminatingly in the Nicomachean Ethics about what he calls the vice of alazony ( alazoneia). The alazôn , the person who suffers from alazony, is the kind of person who exaggerates his credentials. He (the gendered nature of the vice is worth noting) is self-important, self-promoting, narcissistic, boastful. The problem is not that such people make the wrong choice of ends, nor even that they select the wrong means for achieving them. Rather it is that they have a settled disposition to behave like this: alazoneia is in their character, and this is what we dislike in them.'

Richard Smith is a philosopher of social science. His research interests are in the philosophy of social science and in philosophical issues in education, particularly higher education, postmodernity, and the epistemology of educational research. Here he discusses philosophical ideas embedded in educational policy, the REF, the importance of Wittgenstein and Peter Winch, educational research, educational management and change management, impact measures, and why we need the 'quieter virtues' discussed in Ancient Greek texts.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Richard Smith: I studied Greek as one of my three A-levels when I was at school. The set texts included Plato’s Apology of Socrates and parts of Phaedo. The arguments for the immortality of the soul that Socrates offers to his companions in Phaedo seemed to me very weak. This thing called philosophy, though, was clearly worth investigating further if Socrates was ready to die rather than give it up. My teachers directed me to the Greats (or Literae Humaniores) degree at Oxford, to which, knowing no better, I applied. The last seven terms of this four-year degree were at that time devoted to Greek and Roman History, and to Ancient and Modern Philosophy. I had no thought of becoming a professional philosopher. Such a thought could in any case hardly have survived the Socratic style of tutorials with the two philosophy tutors at Merton College, David Bostock and John Lucas, which regularly left me in aporia.

After graduating I became a social worker for a year in rural Northamptonshire, which made me long for urban life again, and books. I found a job teaching Classics and English at a selective secondary state school in Birmingham, wholly untrained: the last year that it was possible to become a teacher in this way. Once I found my feet I was extremely happy there and felt I had discovered my vocation.

By chance one evening in a Birmingham pub I met Bernard Curtis, lecturer in philosophy in the Birmingham University School of Education. I had been reading some philosophy of education as one element of a part-time Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE), which I signed up for in an attempt to improve my credentials as a career teacher. This was based largely on the Master’s programme recently developed at the London Institute of Education; it foregrounded the writings of Paul Hirst, Richard Peters and Robert Dearden, as well as Israel Sheffler from the USA. I found it rather pedestrian and too much in the grip of a dubious version of linguistic or ‘ordinary language’ philosophy, with reliance on ‘what we say’ as the solution to philosophical problems.

Bernard shared my reservations and introduced me to some more sophisticated ones of his own. Bernard and I became good friends. He was particularly interested in phenomenology, whose merits I was slow to see. He was more successful in persuading me to sign up for a part-time MEd by thesis under his supervision. I was clear that this would at least start with critique of the kind of philosophy of education I had recently been introduced to, but I spent nearly a year of my allotted three trying to work out where it would go from there. I began to develop a critique of Paul Hirst’s project, well-known at the time, of distinguishing various ‘forms of knowledge’ as the basis for the school curriculum, and his use of Wittgenstein and his notion of ‘language games’ to justify this.

One oddity here was that what Hirst distinguished as the relevant ‘forms of knowledge’ looked remarkably like the traditional school subjects; another was Hirst’s use of the later work of Wittgenstein to establish a systematic conception of knowledge. This struck me as a perverse way of reading the Philosophical Investigations. In my thesis I argued that there were aspects of knowing that were far more interesting to education in its widest sense of helping young people to develop and flourish than the somewhat desiccated propositional sense that ran through Hirst’s work and that of many of his contemporaries. I took self-deception and wishful thinking as two interesting examples of the ethics of knowing, for reasons I no longer recall. I would never have embarked on this project without the encouragement of Bernard Curtis; I would probably never have finished it had not Robert Dearden moved to Birmingham from the London Institute of Education and taken over its supervision after Bernard moved to a post at Manchester University.

Robert was an exemplary supervisor, insisting on regular meetings and deadlines. He tolerated what he saw as my eccentric approach, while often remarking, sadly ‘Not much about our subject here, though’ – that is to say, this was not philosophy of education as he understood it. The dissertation that I submitted, in 1979, was titled ‘Knowledge, virtue and the curriculum’. On a charitable view, which the examiners took, it was an early exercise in virtue epistemology with leanings towards celebrating what many now call the death of traditional epistemology. While working on my thesis and teaching full-time I was looking for a promoted teaching post: my wife and I were starting a family and needed the money. In late May 1978 I saw an advertisement for a Tutor in Classics and Lecturer in Philosophy in the School of Education at the University of Durham. It seemed a long shot, given that I had only six years’ experience as a school teacher and my thesis was not yet finished. But the long shot paid off, not least in allowing me a light year of university teaching to finish and submit my thesis. So it was that in the autumn of 1978 I became a Lecturer in Philosophy, by what has always felt like a series of accidents.

3:16: You’re interested in philosophical ideas embedded in educational policy. One area of interest – concern actually – is the UK's ‘Research Excellence Framework’ (REF). You don’t find anything to worry about in terms of its cost or whether it’s too subjective, but you do find something problematic with the way research is conceived in terms of outputs making an impact. Can you sketch for us what the REF requires and why is it problematic? And as part of this, can you say why alazony amongst the academics is problematic too?

RS: UK academics need no reminding of the importance of the REF, which has come to dominate university life in this country. It is a process of assessing the quality of research in British universities by a Panel of roughly 25 academics in each relevant field that takes place every seven years. The main object of assessment is publications, which are known as ‘outputs’: in the 2021 REF they will count for 65% of a department’s submission in terms of remuneration. A top-rated (4*) publication in the 2014 REF brought over £50k to the host department over the 7-year REF cycle; a 3* publication rather less than half of that (2* and below, nothing). Along with the stars and the money goes prestige, naturally measured by league tables. The REF has thus made this aspect of research – writing and publishing – difficult for university managers wholly to relegate in favour of, for instance, winning research grants. This is among its merits.This REF process is called ‘expert review’. People worry that it is ‘subjective’: but this is no more so than an art expert’s determination that a particular painting is by Titian, or a football referee’s judgement that a particular tackle did or did not constitute a foul – or indeed academics’ marking of student work. The REF reviewers’ judgements are carefully monitored (so are football referees’): anyone who rates an unusual proportion of ‘outputs’ as high or low is required to read the relevant material again. Panel members are encouraged to discuss material about which they are uncertain with other members, and to return material they do not feel confident to judge for re-allocation. No Panel member evaluates material submitted by their own department; when such material is discussed they leave the room. When I sat on the 2014 Panel these conditions were scrupulously maintained. Members were also required to observe omertà about the scores allocated to particular individuals; only the performance of departments as a whole was finally published. (This, pleasingly, has frustrated Faculty Deans who thought they had found an easy way to decide whom to promote and whom to fire.)

The refusal, across all the Arts and Humanities Panels, to accept proxies (such as the ranking of the standing of journals in which people publish) for judgements about quality, is foremost among the reasons why I think we should hold on tight to the Research Excellence Framework. But there are nevertheless many criticisms that can be made of it. The chief drawback is the clunky and often inappropriate terminology in which it is couched. The very word ‘research’ is often taken to imply specifically empirical investigations, which puts philosophy and other non-empirical investigations on the wrong foot. ‘Excellence’ is a shibboleth that assumes a single scale of quality measurement: good, very good, excellent. It occludes the fact that a piece of academic work is to be understood in different and richer terms: as thought-provoking, as challenging the accepted picture of this or that thinker, as putting a familiar text in a different light, and so on. Talk of a ‘framework’, when it is not simply meaningless, seems to imply anything from an innocuous structure on which anything can be set out for inspection to a nightmarish web from which it is impossible to escape. Worst of all, perhaps, ‘outputs’ belong to models of industrial efficiency and they are the term of art for what emerges from an algorithm, which is precisely what some people would like to see replace professional expertise and judgement. Once they are thus renamed, articles and books appear to be the result of a mechanistic process, eminently suitable to be overseen by university functionaries whose principal concern is to measure and quantify. In this kind of language the academic is now cast as a ‘knowledge worker’, about whom the only important question is whether he or she is, in that ugliest and most diminishing of terms, ‘REF-able’.

A further and significant part (now 25%) of the evaluation of a department’s work consists of its ‘Impact’: that is, the ‘impacts on the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life that were underpinned by excellent research conducted in the submitted unit’. Departments submit a small number of case-studies to justify their claims to having Impact, and the criteria by which they are assessed are tightly defined. Unfortunately the idea of impact has begun to colonise the academic imagination. UK academics from many disciplines are now confusing – whether through deliberate misconstrual, fantasy or honest misunderstanding – the highly specific, and limited, Impact dimension of the REF with the very different criteria for publications. The criterion of ‘significance’ for publications (the other two criteria were ‘originality’ and ‘rigour’) meant academic significance, and not ‘Impact’ in the sense that the REF used the term. It is common these days to hear people asserting that ‘it’s all about impact now’, or priding themselves on the usefulness of their research by contrast with people who merely write journal articles or books. I should add that I have here left out a lot of detail about the operation of the REF for the sake of brevity. It would not do though to omit that the report from the Education Panel on the 2014 REF spoke very well of the philosophy of education ‘outputs’ they had assessed and showed neither surprise nor disappointment that philosophers of education made little contribution to Impact.

3:16: You find fruitful aspects of Wittgensteinian rule following to suggest how educational research should be done, citing Peter Winch approvingly when he writes that we should always consider ‘… what it makes sense to say’ about certain educational phenomena, and how these meanings stand against understanding a wider form of life.’ Can you say what you take this Wittgesteinian insight to be claiming and why it’s important for doing educational research?

RS: The default model of educational research is empirical and dominated by the aspiration to be as ‘scientific’ as possible. This is true from the naïve undergraduate student confronted by the requirement to write a dissertation all the way to the idea that randomized control trials (which have of course escaped from their natural home in scientific medical research) constitute the ‘gold standard’ for research in education.

Wittgenstein famously wrote ‘A picture held us captive’. Just as Wittgenstein came to see that the ‘picture’ of science had captivated him, not least by inspiring much of the content and style of the Tractatus, so too the idea of science seems to hold all social science and in particular educational researchers in thrall.

Against this orthodoxy I have persistently argued that good educational research can often be philosophical rather than empirical. Happiness is a good example. It’s not – as non-philosophers sometimes imagine – that before we can do the real research we have to define happiness, and philosophers can come in handy here before passing things over to psychologists and other specialists. Rather we have to think carefully about what kinds of happiness are educationally desirable – the satisfaction of mastering another language over years of hard work, perhaps, or learning to play a musical instrument well. This calls on our understanding of the human condition, so it might be called an empirical matter, but this is not the empiricism of surveys, questionnaires and the accumulation of ‘data’. It requires a grasp of the subtleties of language, language ‘at full stretch’, as the philosopher Cora Diamond puts it, which is found in poets and novelists as much as among philosophers. And it involves a high level of alertness to the ways that technical and overly theorized language tends to creep in and distort our attempts to understand the world.

This is well illustrated by Rai Gaita, in his Introduction to recent editions of Winch’s The Idea of a Social Science. Gaita imagines a social scientist researching discipline procedures in schools. She expects the teachers to discuss these in terms of ‘behaviour modification’ and is disconcerted to find that they use a more everyday language through which they try to identify the meaning of children’s behaviour and adults’ responses to it.

3:16: Does all this mean that you are against scientific educational research and for something that, if science is modernist, is romantic? Are you wanting a new romantic turn in educational research?

RS: I don’t know what ‘scientific educational research’ means. Neuroscience might seem the perfect example, but the distance between neuroscience and education is very wide, and unfortunately it is full of ‘neuromyths’, such as that every individual has their preferred learning style (which naturally it is the job of the educator to discover and meet). Randomised control trials (RCTs), as I mentioned above, carry the aura of science because of their origin in medicine, where they are unquestionably important. Education however is different. Here RCTs are confounded by the proliferation of variables. A free school uniform policy which encourages school attendance among Kenyan children (a policy change that attracted a lot of interest a few years ago) cannot be assumed to be the right thing for Manchester, where for many young people school uniform may be the opposite of a symbol of high status. Furthermore while it is part of RCTs’ schtick that they discover ‘what works’, it all depends on what counts as ‘working’. Synthetic phonics has been hailed as the royal road to literacy, but of course it depends on what you mean by literacy. Many of the trials seem to consist of giving children training in the use of synthetic phonics and then testing them not long afterwards (to avoid the problem of intervening variables) – unsurprisingly, they tend to do better in the tests than children who weren’t given the training. In any case doing well on a phonics test is a long way short of what many people would think of as being literate.

No doubt the idea of a ‘romantic turn’ in the social sciences sounds odd. But it is taken seriously by some eminent social scientists today. John Law writes in his significantly titled After Method: Mess in Social Science Research (2004) that we have focused in our research too narrowly on highly stable realities such as global CO2 emissions and income distributions, ‘distorting into clarity’ other phenomena which are ‘vague, diffuse or unspecific, slippery, emotional, ephemeral’. He asks how we might apprehend some of the realities we are currently missing, whether it is possible to know them well, and indeed whether it is desirable to ‘know’ them at all. The line of thought leads in the direction of the later Wittgenstein, who writes of the importance of ‘imponderable evidence’ ( Philosophical Investigations p. 228): that is, evidence that cannot be precisely calculated, weighed and measured, but which is good evidence nonetheless.

‘Romantic’ research in education, or social science more widely, is research that foregrounds sensitivity, attunement, listening; understanding rather than knowledge, interpretation rather than the quest for certainty, hermeneutical rather than scientific inquiry. The astutest analysts of this are Hans-Georg Gadamer and Martin Heidegger, who strangely do not seem to have had much influence on modern philosophers of education.

3:16: You’ve engaged with the ideas around management of change that’s prevalent in education at the moment. You see this language of change as ‘invariably a euphemism for the impoverishment of education and the annihilation of its ideals, together with the deprofessionalisation of teachers and other educators.’ Can you sketch for us your thoughts here.

RS: Excited talk about the importance of the management of change has taken root in the world of education, having migrated from Business Schools and the patois of management consultants. Apparently it is possible to be an expert in the management of change without knowing much, or indeed anything, about just what you are trying to change. If a university department of Computing, for example, was worried that it was becoming a little staid it could call in a Change Expert who, without having much notion of Computing as an academic field, could oil the wheels of the Computing specialists on the basis of his or her command of a handful of mantras such as ‘you cannot mandate what matters’ (complex change cannot be forced) and ‘Change is a journey, not a blueprint’ (change is uncertain and often requires changing trains along the way, which is positively exciting, apparently). A particularly revealing slogan is ‘Every person needs to be a change agent’ (change cannot be left to a cadre of experts, despite plentiful evidence that those uttering such slogans think they are experts in the field).

Thus the idea of the university is indeed on the move. Everything must become more ‘operationally efficient and effective’, or words to that effect. Increasingly universities look to Starbucks or IKEA for models of change management. The latest slogan is ‘agile management’ which, with its suggestion that hopping from one foot to the other is the mark of the good manager, seems likely to cause further damage. Management of change cant should be vigorously ridiculed by anybody with the energy, wit and security of employment to do so. This is not a particularly philosophical matter, though Socrates, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and others seem to have thought that philosophers ought to make mockery part of their trade.

Naturally there are aspects of modern education that I would like to change. At the same time I wouldn’t dress up my preferred changes as ‘reforms’, a word that casts teachers and academics as negligent or incompetent, and there is a lot that I would prefer to stay as it is or even to return to the old days, for example when lecturers had time to read books and teach seminar groups small enough at least to learn the names of their students, and school teachers were not exhausted by bureaucratic demands.

3:16: One of the ideas that emerges from your critique of the current state of education is your belief that we need what you call quieter and gentler epistemic values. You champion the epistemic state of ‘unknowing’, which is not ignorance although it does have mystical tints. Can you tell us first of all what this state is contrasting itself against – what are the louder, harsher epistemic states that you’re suggesting have captured education at the moment?

RS: Current emphasis on the importance of ‘impact’, which often seems to come from a misunderstanding of the demands of the REF (see above), is just one of the factors that threaten to reconfigure our idea of the academic virtues. New media and online platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, as well as blogging and linking your latest publication from your emails, and publishing in open access journals rather than ‘burying your work in the old-fashioned ones’, offer possibilities of advertising one’s research that young scholars in particular often feel they dare not resist. They are told in Seminars on How to Get your Research Known ‘Don’t just publish your research – shout about it from the roof-tops!’ All this is understandable, but self-importance and self-aggrandisement, the ‘bigging up’ that has now entered the language, have replaced the ideals by which I was so impressed when I joined my university forty years ago. Scholarly diffidence and modesty were abundant, notably among those who had most to boast of, had they chosen to do so. The classical Greek dramatists saw arrogant self-confidence or hubris, which is closely related to the vice I have described, as prevalent in their time and before.

Aeschylus represents it in the person of Agamemnon, who led the Greek army that triumphed over Troy: he seals his fate at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aigisthus when he sets foot on the red carpet they have laid for him and claims the role of returning hero. Sophocles lived long enough to see it in the disastrous Sicilian expedition in 415 BCE with which Athens had hoped to secure a decisive advantage over Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. Its leader was the beguiling, charismatic and egotistic Alcibiades, the very model of what we might now call ‘entitlement’.

A generation later Aristotle wrote illuminatingly in the Nicomachean Ethics about what he calls the vice of alazony ( alazoneia). The alazôn , the person who suffers from alazony, is the kind of person who exaggerates his credentials. He (the gendered nature of the vice is worth noting) is self-important, self-promoting, narcissistic, boastful. The problem is not that such people make the wrong choice of ends, nor even that they select the wrong means for achieving them. Rather it is that they have a settled disposition to behave like this: alazoneia is in their character, and this is what we dislike in them ( NE 1127b 16-17).

I welcome the relatively recent return among philosophers to discussion of the epistemic virtues and away from the traditional concerns of analytic epistemology, such as Gettier problems (is knowledge justified true belief?). Yet there are two oddities here. First, virtue epistemologists show little interest in the epistemic vices which, being all around us – as Aristotle saw – deserve some attention. Secondly, they tend to readmit the old focus on knowledge and truth: the good knower is simply someone who maximises her surplus of truth over error. Then too the intellectual virtues that are generally supposed to be at the heart of the good knower tend to be the tough-minded ones: intellectual carefulness, courage, rigour and honesty, for example. Little attention has been paid to what might be called the quieter epistemic virtues such as intellectual modesty and diffidence, to keeping ourselves in a cordial relationship with what we do not know, to what the poet Keats called the negative capability of being able to live with uncertainties, mysteries and doubts, ‘without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’. (The irritability deserves more attention than it has had.)

There is indeed sufficient sense of mysticism here to worry analytic philosophers. I doubt if they will welcome reassurance that the tradition of valuing what I call ‘unknowing’ goes back at least as far as Plato. He generally depicts Socrates’s interlocutors less as lacking in knowledge than as being too knowing. Euthyphro is certain that his prosecution of his own father meets divine approval. Theaetetus seems to think that gaining knowledge is a straightforward matter of proceeding from basic axioms to what can be deduced from them, just like in geometry, in which he is a precocious student. Phaedrus is confident that sitting at the feet of Socrates under a plane tree by the river Ilissus makes him a philosopher too.

Moreover many of the Platonic dialogues begin by shaking our confidence that what follows can be taken literally and at face value. The Symposium is striking example, not least because the narrator, Apollodorus, begins by declaring that he is an authority on what someone has just questioned him about; which, strangely, the reader is left to infer is what was said in the speeches Alcibiades, Aristophanes, Socrates and others made at Agathon’s famous dinner-party all those years ago. Such egregious confidence on Apollodorus’s part, especially when the opening pages of the dialogue give an impenetrable account of how the story of the dinner-party was passed down from one person to another.

Certain later philosophers, such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche (though some would say they are not philosophers) have also found ways of destabilizing their own texts (such an unphilosophical thing to do). They both employ masks (so it is both they and someone else who speaks); and, like the Socrates who Plato presents to the reader, they are prodigious ironists. You can never be certain that you know just what an ironist means. Indeed, one distinguished ironist of my personal acquaintance often says – ironically, no doubt – that he isn’t always sure himself.

3:16: And are there 5 books you can recommend to the curious readers here at 3:16?

RS: Five books:

Jonathan Lear, Open Minded: Working out the Logic of the Soul

Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness

Plato, Phaedrus, Theaetetus, Phaedo … the ‘middle’ dialogues

Max Statkiewicz, Rhapsody of Philosophy

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Times Series: the index of interviewees

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

NEW: Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series