What the Women Were Up To

Interview by Richard Marshall

'They were mentors—Anscombe and Foot, especially—to a lot of other women (and men). If we’re not evenly balanced yet, we’re nonetheless in a very different place from when these philosophers began their careers, and you could count on your ten fingers the number of women in philosophy in the English-speaking world.'

'Midgley was ahead of Foot in thinking that “rational” (if it’s supposed to be a compliment) must mean something like “sane.” And to be sane, Midgley judged, is to live in frank acknowledgment of the diversity of human motives and their significance.'

'Anscombe was impatient with anything slick or glib in philosophy, as you say. Some of it may have been an inheritance from her mentor Wittgenstein, who felt the same way. But she also came to Wittgenstein like that. In her early adulthood, she was profoundly distressed by philosophical questions she couldn’t see how to answer, and had no patience for anyone who proposed to answer these questions without acknowledging how hard they are. It offended her. '

'What Murdoch proposed was twofold: first, that this unexplored background picture was driving the ethical thought of her contemporaries on both sides of the Channel; and second, that the appeal—the gravitational pull—of this background picture was a legacy of cultural Romanticism.'

Ben Lipscomb specializes in contemporary ethical theory, with side-interests in American agrarianism, biomedical ethics, the history of philosophy (particularly the history of ethics), legal interpretation, town planning, and Christian worship. His overarching concern, across all these areas, is with issues of character formation.Here he discusses his new book about four important philosophers who were women at Oxford in the immediate post-Second World War, about why they were important, about seeing themselves as ‘daughters of the Armistice’, religion and the “Dawkins Sublime”, AJ Ayer, Richard Hare, Murdoch and Sartre, Murdoch and Wittgenstain, Anscombe and her opposition to Truman, Foot and Anscombe, Foot's rationality, Midgley and biology, beastliness, and their legacies.

3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

Ben Lipscomb: I became aware of philosophy as a teenager, when I grabbed some books by Peter Kreeft off a library shelf. They’re books of imagined dialogues between Socrates and a variety of modern and contemporary figures. Kreeft has Socrates do what he did in ancient Athens—expose the confusions underneath people’s platitudes. I found enticing the idea of reason as a force—as a capacity to make people rethink. I’m not sure that was entirely good for me. But it did make me aware of philosophy as an activity, and I signed up for a course as soon as I got to Calvin College. It was there, taking ethics with John Hare, that I decided I was going to pursue this through college and beyond. I knew I was good at explaining things, and would make an effective teacher. It was only a question of what I wanted to teach and at what level. Reading Aristotle and Kant with John settled it.

3:16: You have recently written about four important philosophers who were women and Oxford graduates at a time – the forties onwards - when there were big changes happening at Oxford and in philosophy. What were they and how did changing roles for and attitudes towards women in the early years of the century leading up to and including their time at Oxford University impact on Iris Murdoch, Mary Midgley, Phillipa Foot and Elizabeth Anscombe?

BL: What had changed in philosophy—particularly Anglophone philosophy—was that a method and a background picture of reality had established themselves as orthodoxies. The method was close analysis of language; the background picture was one in which nothing is real but the objects of the hard sciences. Some young men found these philosophical orthodoxies congenial, but these women didn’t. That change came on gradually but inexorably over the 30s and 40s. At Oxford, what changed—very suddenly, just as these four were beginning to study philosophy seriously—is that another war broke out and almost all of Oxford’s young men were called away to fight. This left the women almost alone as the only advanced students of philosophy. And they shared a brilliant, eccentric, and sacrificial tutor, Donald MacKinnon, who not only invested in them, but also suggested by word and example that there were other ways of doing philosophy besides the orthodox one.

3:16: A central question for you is to try and answer how these four turn into the philosophers that they did. You say that of all four they were in an important sense ‘daughters of the Armistice’ and that they all grew up in a culture that understood itself as living between an unprecedented outbreak of ferocity and something worse to come. Can you say something about this and how did this affect their subsequent lives and works?

BL: This sense of living on the brink, which Richard Overy documents in his book, The Morbid Age, expressed itself especially in an urgent sense of political and social responsibility. It’s similar to our moment. The generation emerging into adulthood in the late 30s was just too young to do anything about the Spanish Civil War. But they were deeply engaged with the possibilities of the Communist and peace movements, and then were drafted into—or watched from home—a world war. That primed them, I think, to be dissatisfied with the orthodoxy of their day: again, the view that nothing is real but the objects of the hard sciences. They thought that this orthodoxy didn’t have enough to say—or said the wrong things—about the political and social questions of their moment. Philippa Foot in particular pointed to her encounter with early footage from Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald as a moment of awakening. She wanted to be able to say something more about what Hitler and his followers had done than the dominant philosophy of her time permitted.

3:16: How important was religion in their formation as philosophers – Anscombe and Murdoch were religious – Anscombe from pretty early on despite her mother’s misgivings – and Murdoch for a time – but was religion, - and what kind of religion – important even when philosophizing? Do you think their views about the Dawkins Sublime, for instance, were influenced by religious thinking of some sort?

BL: The “Dawkins Sublime” is my coinage. And Dawkins himself is just one exponent of it. He is relentlessly quotable, and I found a quote from him that perfectly expresses the attitude I have in mind. What is the Dawkins Sublime? It’s the insistence that nothing is real but the objects of the hard sciences, together with a valorization of that insistence. It swathes with an atmosphere of heroic grandeur the notion of staring into the abyss—of acknowledging that the world is meaningless, valueless. Murdoch in particular criticized this attitude. She lost any semblance of Christian faith in the 50s, but then began trying to describe a post-Christian faith in Goodness as an abstract ideal. She did think that the world could be pretty bleak. But all along, she was sharply critical of attempts to have it both ways: to suggest both that nothing is truly noble and that it is noble to steel yourself and confront this.

About the other three: Foot was a committed atheist, and generally wouldn’t be drawn into further conversation about it. Midgley’s father was an Anglican vicar, but she soon walked away from her family’s faith. She expected to have some sort of transcendent religious experience and when it didn’t happen, she didn’t know what to think. She later compared Christianity to an engine she couldn’t start. She was never hostile to belief, though, and had little patience for people (like Dawkins) who caricature it. She’d seen too much of Christianity at its best—for instance, in her mother and father. Late in life, like Murdoch, she became interested in somewhat mystical ideas: in Midgley’s case, the Gaia hypothesis.

But Anscombe’s Catholic Christianity was absolutely central to her identity and is important for understanding why she was invested in some of the topics she addressed. She didn’t write exclusively for Catholics, but her work in action theory (for instance) was a protracted, lucid defense of a traditionally Catholic view of action. It’s a view that lots of non-Catholics find compelling, but it’s very much in that tradition.

3:16: How important was AJ Ayer in their formation of their views towards ethics? Was it a combination of the concentration camp pictures, their dislike of logical positivism and what you call ‘The Dawkins Sublime’ that led them towards their distinct ethical philosophical positions?

BL: Ayer was the one who set the terms for discussion of ethics (and everything else) in the 40s. Though his views in ethics were quickly superseded by C.L. Stevenson’s, and then by R.M. Hare’s, it was Ayer’s background picture that my subjects wanted to overturn. They began looking for alternatives, which they found in some of the premodern philosophers they had read at Oxford.

3:16: Hare was a key figure at the time – his approach to ethics was to challenge the ‘emotivism’ of Ayer and Stevenson of the day wasn’t it? So what did this theory claim, why was it considered necessary – and why did it fail to disconnect ethics from the Dawkins Sublime? He did have part of a thesis that did actually think descriptions and values could be brought together didn’t he – but he was dissuaded by Ryle from publishing it in 1950 when he published the first part as ‘The Language of Morals’?

BL: Hare deserves a biography of his own. And I find this aspect of his biography particularly fascinating: his flirtation with and then withdrawal from views later associated with Anscombe, Foot, Midgley, and Murdoch. But let me take your questions in order and describe the theory first. Hare observed that neither Ayer’s philosophy nor Stevenson’s made room for logical inferences about ethics. They both treated ethical statements as manifestations of subjective attitudes. And an attitude isn’t a premise that can be worked into a syllogism. Hare saw his way around the problem, suggesting that ethical statements are “universal prescriptions”—imperatives directed jointly to oneself and others—which could stand in logical relations to one another. But Hare didn’t change the background picture.

Where did our universal prescriptions come from, according to Hare? They were grounded in unfettered choice, he thought. We make “choices of principle” and then live up to those choices—or don’t. Hare preserved from Ayer and Stevenson the thought that you can’t be right or wrong about your deepest ethical commitments—because nothing is real but the objects of the hard sciences. The only mistake you could make about ethics, then, is to be inconsistent. Back to Hare’s biography. I don’t think he was insincere. Hare was nothing if not sincere. But for someone who had kept himself alive and sane as an abused prisoner of war, Hare was surprisingly sensitive to philosophical peer pressure. He suppressed the remarkable book he wrote during his imprisonment because it didn’t conform to the orthodoxies at Oxford after the war. And then he excised the part of his T.H. Green Prize thesis that brought him closer to the views of Foot and the others. Hare’s peers—his mentors, especially—made clear to him that the only acceptably modern view was that ethics is entirely subjective, and he accepted that.

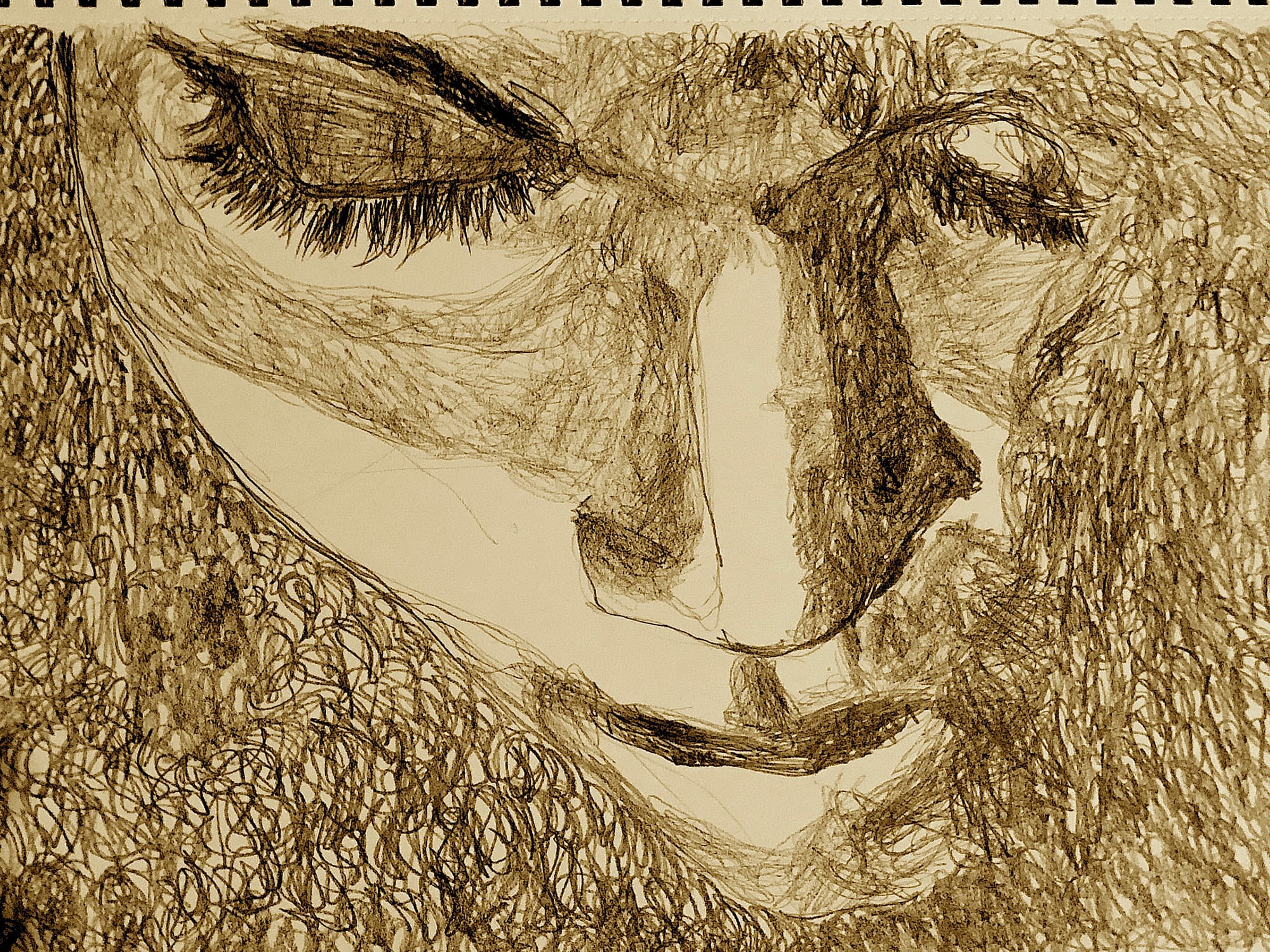

[Murdoch]

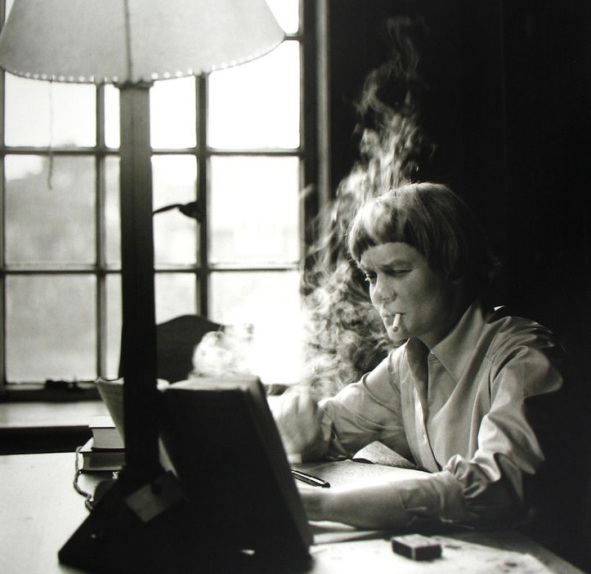

3:16: Murdoch, Midgley, Foot and Anscombe were looking to get ‘thick’ concepts that wrapped up description with evaluation – in other words to push back against Hare and his view that the Nazis had done nothing objectively wrong. They were out to smash the picture that held Hare and the rest in its grip – you say Iris Murdoch was the one who diagnosed the issue best. What did she propose – and was it as a philosopher (she always seemed to doubt whether she was any good at philosophy didn’t she?) or an existentialist novelist that she did it? How important was Sartre in this?

BL: Sartre is crucial—Sartre and the whole circle depicted in Sarah Bakewell’s book, At the Existentialist Café. Murdoch went to Brussels right after the war and met Sartre. But even before they met, she was already reading everything she could get her hands on, by him and by the other leaders of French existentialism. And she saw a deep kinship between the ideas of Sartre and the other existentialists and the superficially very different ideas circulating at Oxford. Sartre, like Hare, propounds an ethics of radical choice.

Murdoch’s insight was that there was something in the spirit of the age leading these two groups of philosophers—who scarcely read each other—to articulate such similar ideas. They shared a background picture, though neither of them argued for it. What Murdoch proposed was twofold: first, that this unexplored background picture was driving the ethical thought of her contemporaries on both sides of the Channel; and second, that the appeal—the gravitational pull—of this background picture was a legacy of cultural Romanticism. It was the Dawkins Sublime: an attraction to the idea that we live in a world bereft of meaning because of the courage and dignity one can show in acknowledging this. Thinking back to a question you asked earlier: it’s relevant that Murdoch was seriously exploring Christianity in the period when these insights came to her. She didn’t feel the inevitability of the value-free background picture herself, which set her up to ask, “what is the attraction?”

3:16: How much was she influenced by Wittgenstein? She wrote far more about Kant, Kierkegaard, Sartre, de Beauvoir and Weil but with Anscombe as an influence did Murdoch take from Wittgenstein her view that both the British moralists and the continental existentialists were gripped by the same damaging picture? And would this linguistic turn philosophy also be influenced by the ordinary language approach of Austin, and how did Murdoch respond?

BL: Wittgenstein was a substantial influence on all four of these thinkers, via Anscombe. Anscombe, as Wittgenstein’s friend, translator and (in the 1940s) devoted disciple, shared with her friends her translation-in-progress of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, initiating them into Wittgenstein’s genius as she understood it. Midgley captured this in her 2005 memoir, The Owl of Minerva. The chief thing they all took from Wittgenstein was a determination to set ethics in its context, within the human “form of life.” Anscombe and (especially) Foot’s revival of the virtue-and-vice-based ethics of Aristotle and Aquinas, and Midgley’s later efforts to bring moral philosophy together with the science of animal behavior—all are expressions of this basic conviction: that the task of ethics is to identify what facilitates the flourishing of creatures like us.

Murdoch’s ethical outlook was more indebted to Plato than to Aristotle or Jane Goodall. But she too thought about ethics with reference to our characteristic psychological needs and temptations. This is one of the great themes in her fiction as well as in her philosophy.

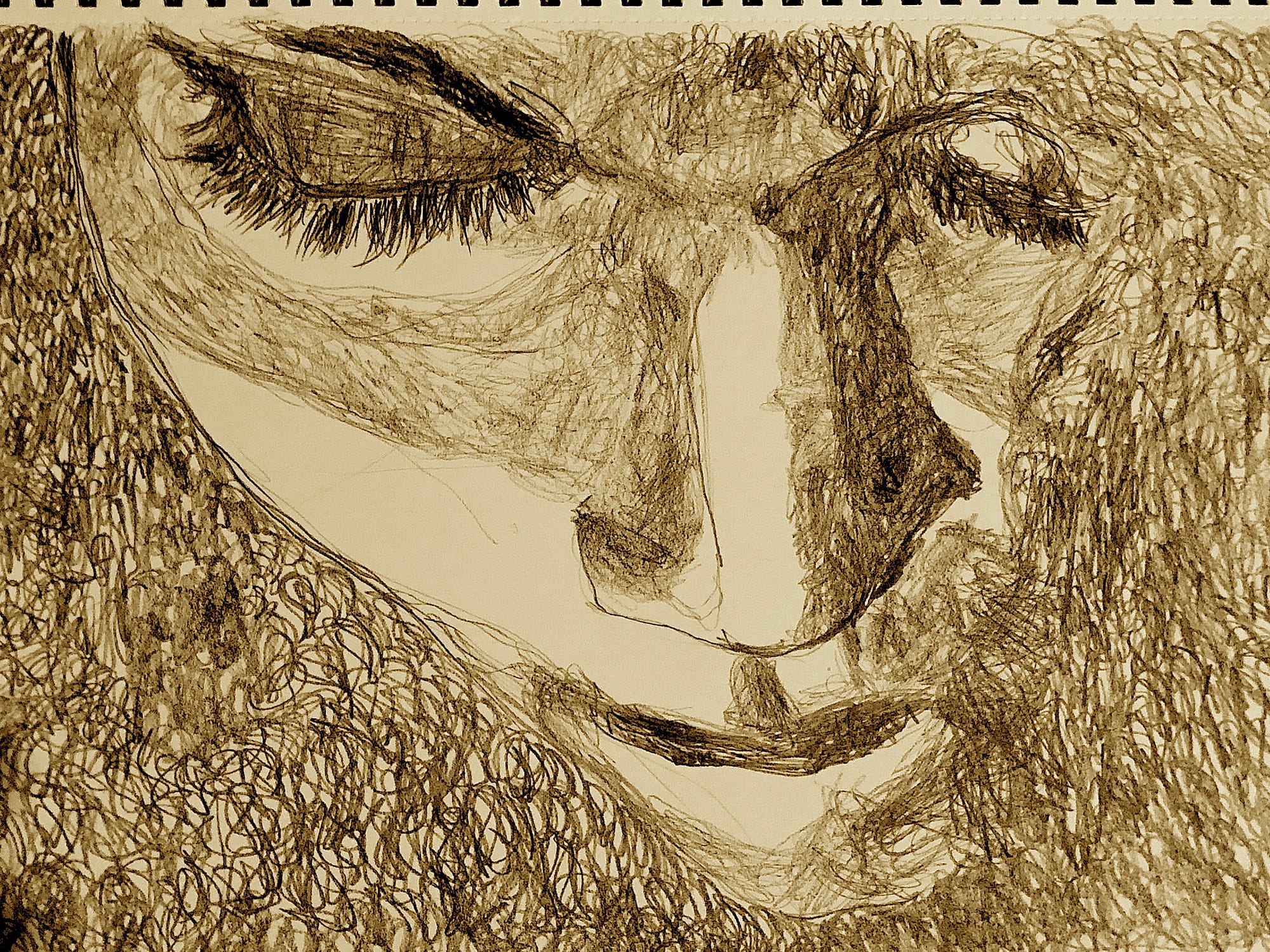

[Anscombe]

3:16: If Murdoch was a pretty weak philosopher Anscombe was a strong one. She adored Wittgenstein and hated Austin – what were the reasons for this distinction - and does it help us explain why she thought CS Lewis wasn’t serious and that somehow being serious was the mark of proper philosophy, that it wasn’t enough to be clever, to be good at dialectical competitiveness and showing others they were wrong and so forth, that you shouldn’t be glib but rather you should recognize that a proper philosophical question be hard?

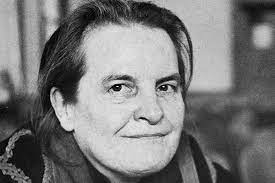

BL: I don’t agree that Murdoch was a weak philosopher. She was a philosopher of a different kind than Anscombe and Foot: a kind not much valued in mid-century Oxford. But Anscombe’s excellence in that domain is beyond dispute. Anscombe was impatient with anything slick or glib in philosophy, as you say. Some of it may have been an inheritance from her mentor Wittgenstein, who felt the same way. But she also came to Wittgenstein like that. In her early adulthood, she was profoundly distressed by philosophical questions she couldn’t see how to answer, and had no patience for anyone who proposed to answer these questions without acknowledging how hard they are. It offended her.

More than that: Anscombe’s faith and her philosophy were intertwined from early in her career. According to the greatest Catholic philosopher, Thomas Aquinas, God is the source of truth, and so we honor God by getting things right. Sloppiness of thought, by contrast, dishonors God.

3:16: Her opposition to Truman receiving an honoury doctorate was important wasn’t it and her reasons ended up being her book ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’ didn’t it? What was her reasoning, and why was it so explosive for Oxford philosophy , destructive to Hare’s position and important for changing the picture standing behind the moral theories of her time? It amounts to an Aristotelian turn in ethics doesn’t it?

BL: This is the turning point of her career. Certainly, it is what drew her into moral philosophy. She was appalled, not only that Oxford would award Truman an honorary degree, but also that her colleagues would defend this decision, or simply shuffle their feet and say nothing. Her reasoning was simple: Truman ordered the killing of masses of Japanese civilians as a means to his strategic ends. And killing people as a means to your ends—no matter how noble those ends—is murder. This was an old, well-recognized principle of just-war theorizing and enshrined in international law. How had her colleagues forgotten it? (After the vote on the degree went against her, she wrote a newspaper article, offering a reward to anyone who could show that Truman’s action was permitted under international law. It was never collected.)

Anscombe concluded that her colleagues were forgetting or ignoring this basic principle because they’d been corrupted by bad thinking about what it is to act intentionally. So she set to work on a series of pamphlets, broadcast talks, and lectures, all of which called out the “consequentialism” (she invented the word) of her peers. She said that it would improve the thinking of her peers if they took more instruction from Aristotle. Which inspired a number of people to try, starting with her colleague, Philippa Foot.

[Foot]

3:16: Foot was philosophically influenced by Anscombe (and Wittgenstein – ‘why didn’t you tell me later’… ) but by others too - she found Aquinas could answer Ayer , Hare and even Nietzsche didn’t she? So how was Aquinas able to do this in a way that satisfied Foot – was this another version of Anscombe and Wittgenstein’s approach or was it different in important ways – she was an atheist wasn’t she unlike Anscombe (and Murdoch too I suppose?) – did this matter in differentiating them philosophically?

BL: Foot read Aquinas at Anscombe’s recommendation; she admired Anscombe ardently, and was prepared to take any recommendation from her colleague seriously. What Foot got from Aquinas was a picture of what virtues and vices are. They’re not just conventionally approved traits. They’re traits that help us succeed in characteristically human activities. What makes a human life? Endless—and endlessly diverse—rational activities, most of them cooperative. There are traits that make people better at these activities and traits that make people worse at them. The former are the virtues; the latter are the vices. The practicality of Aquinas’s thought—the way he was prepared to tether even minor virtues and vices to what makes life with others go well or badly (Foot liked the example of “loquaciousness”)—was a revelation to Foot.

3:16: She seems to have repudiated her early philosophy by the 1960s - can you sketch for us how she came finally to commit to the thesis of ‘Natural Goodness’ she published when she was 80, and what the thesis was and how it differed from her earlier approach?

BL: Foot’s testimony is that she was held captive by a picture of rationality: that it’s just choosing effective means to your ends, whatever those ends might be. For a long time, then, she thought that a canny evildoer couldn’t be irrational. Through the influence of a beloved younger colleague at UCLA, Warren Quinn, Foot came around to thinking that “rational” means something more than just “choosing effective means to your ends”. There are some ends that are bad, or a waste of time, and it’s actually irrational to pursue them—even if you’re very efficient about it. The interesting thing, to me, is that this is what Foot’s friend Mary Midgley had been saying since the 1970s. But, like Murdoch, she’d been saying things from outside of the philosophical guild.

[Midgley]

3:16: Mary Midgley came to write some time after her university friends Murdoch, Foot and Anscombe had. She is multidisciplinary and more into biology than the others, - she read Lorenz and Tinbergen - so in that sense is a naturalist. What was her breakthrough book ‘Beast and Man’ about and how does it concern itself with the same things as the other three, for example, answering Austin, being Wittgensteinian, changing the narrow atmosphere of Oxford linguistic moral philosophy etc? Was the fact that she was in Newcastle and away from Oxford helpful to her?

BL: Going to Oxford in 1938 was essential to Midgley’s development. Getting away from Oxford in 1950 was equally essential. Without the pressures of teaching and without peer pressure from a close-knit community of fellow philosophers, Midgley was able to simply absorb for over a decade: watching her boys grow and thinking about what she was seeing, reading every book about animal behavior she could find. If she’d had to impress colleagues who didn’t think of her new interests as appropriately philosophical, that would have hindered her growth. She resumed teaching in the 1960s when her last son went to secondary school and almost immediately offered a course on ethics and animal behavior, with the aim of getting her own ideas clear. She started to write about this in the early 70s, which led to a contract for her first book.

That book, Beast and Man, came out at the end of her 50s! Midgley’s central thought is that we use reason to harmonize the variety of instinctual motives our evolutionary past has given us. We mustn’t dismiss any of these motives, even aggression. Rather, we must ask ourselves what role each plays in our lives and find ways to keep it in balance with the others. It’s in some ways a very common-sensical view. It’s also provocatively anti-reductionist. There isn’t one ultimate motive for human beings. There isn’t one good motive. There’s a whole messy array, and we have to find ways to do justice to all of them.

3:16: How does her notion of beastliness detonate ideas about rationality, and why did Foot miss the importance of this even though they were deep friends?

BL: As I remarked earlier, Midgley was ahead of Foot in thinking that “rational” (if it’s supposed to be a compliment) must mean something like “sane.” And to be sane, Midgley judged, is to live in frank acknowledgment of the diversity of human motives and their significance. Foot and Midgley made different contributions to the project of reviving a naturalistic ethics. Foot, as a highly talented Oxford insider did something Midgley couldn’t have done: she poked holes in Hare’s linguistic analysis and suggested that something naturalistic should replace Hare’s moral philosophy. For her part, Midgley was the only one of her friend group who knew enough biology to develop that suggestion in a robust, empirically informed way.

Why did Foot miss the significance of Midgley’s work? Foot was deeply embedded in the professional philosophical community. If she hadn’t been, she wouldn’t have achieved what she did. But a side-effect of being committed to the standards of that community was that Foot didn’t see what her friend was doing as “philosophy.”

3:16: So what do we make of all this and their legacies? That they were impressive women ‘up to something’ in the male bastion of academic philosophy is something, although the continued gender imbalance in philosophy is hardly a roaring success if we’re to see them as opening the gate for women: contemporary moral philosophy has certainly taken on some of their lessons – all but Murdoch seem to have been impressive philosophers and the Trolley Problem remains a hot topic – but many find the way and the content of this domain little more than refining the etiquette and received wisdom of the academic professorial class (often with a whiff of high end Christianity) rather than a reevaluation of all values that the images from the concentration camps demanded: and although you don’t think much of Gellner’s challenge to Oxford language philosophy and Wittgenstein’s baleful influence overall it’s hard after reading your book not to think that he was right to be annoyed by its parochialism and that Wittgenstein was little more than a cult leader of diminishing returns, where if language was to be a philosophical topic it was lessons from Chomsky and Fodor that set the agenda rather than later Wittgenstein? (I’m obviously being a bit provocative here!!!!)

BL: That’s a lot of questions. I’m going to focus on the first, because it points toward the rest. What difference did these philosophers make? They were mentors—Anscombe and Foot, especially—to a lot of other women (and men). If we’re not evenly balanced yet, we’re nonetheless in a very different place from when these philosophers began their careers, and you could count on your ten fingers the number of women in philosophy in the English-speaking world. Intellectually, they did a lot to break the grip of an orthodoxy that makes important things unsayable. Not everyone is in the grip of that orthodoxy, but many were and are, and when you are in the grip of an orthodoxy, it is liberating to see intelligent people challenge it and suggest what could take its place.

I might like to tell the story of philosophy in the popular imagination in the mid-twentieth century: how Oxford philosophy became something educated British people were supposed to know about, and how the backlash against that began. I think the backlash might have had as one of its sources the elite promotion of philosophy as high culture on the BBC Third Programme at the time. But I’m puzzling about it. I don’t think the backlash from Gellner and others really touches the work these four were doing. But it might lead us into the weeds to go much into that!

3:16: And finally, for the readers here at 3:16, are there five books you can recommend that will take us further into your philosophical world?

BL: Let me mention one by each of my four subjects—a suggested point of entry into their work. And then one more that I think your readers might never have read—and might love.

G.E.M. Anscombe, Collected Philosophical Papers, Vol. 3 (Blackwell) Anscombe’s daughter Mary Geach Gormally rightly observes that, if her mother’s philosophical writings were a dessert, they would be panforte: dense and chewy, requiring extra time to ingest. For someone new to Anscombe, I would recommend this volume of her essays, on ethics and philosophy of religion—many of which were written for non-specialist audiences. “War and Murder,” especially, captures Anscombe’s central ethical concerns. Like her pamphlet protesting Harry Truman’s honorary degree (also included), it was hugely influential on later writers about the ethics of war.

Philippa Foot, Natural Goodness (OUP)Foot liked to quote a remark by Wittgenstein: that in philosophy, it’s hard to work slowly enough. It was a joke between her and her friends that if anyone had met his standard, she had. Her first and only monograph appeared when she was 80. There are wonderful essays in her earlier collections: Virtues and Vices and Moral Dilemmas. Readers might be especially interested in her essay “Abortion and the Problem of Double-Effect,” which introduced the famous runaway-trolley thought experiment. But Foot’s views were always in motion. This short book crystallizes the ones she reached by the end of her career.

Mary Midgley, Wickedness (Routledge)I love Midgley’s sprawling first book, Beast and Man. It has one of the best opening lines of any book of philosophy: “We are not just rather like animals; we are animals.” Midgley was pithy like that, and I can recommend almost any of her books to a new reader. But my first suggestion would be Wickedness, her most tightly constructed book.

Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good (Routledge)Murdoch, like Anscombe and Foot, was most in her element writing philosophical essays, not philosophical books. And what essays they were. Murdoch had a rare gift for speaking simultaneously—and inspiringly—to professional philosophers and educated general readers. The three essays in this collection are justly her most famous.

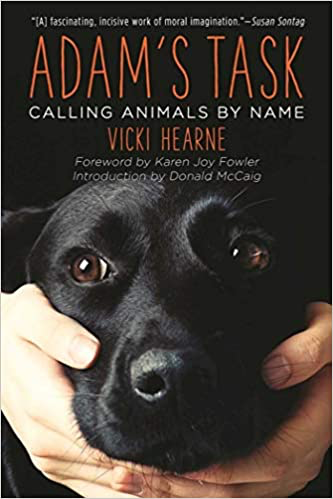

And finally: Vicki Hearne, Adam’s Task (Knopf)I wish Hearne hadn’t died young. An animal trainer, poet, and philosopher, she was an allusive but brilliant writer who made me care deeply about things I’d never considered, like whether American Staffordshire Terriers (pit bulls) get a bad rap. Hearne also made me see for the first time—before I’d read Midgley, and before I really understood the others—the close analogies between human excellence and animal excellence, human happiness and Animal Happiness (the title of another of her books).

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER

Richard Marshall is biding his time.

Buy his second book here or his first book here to keep him biding!

End Time series: the themes

Huw Price's Flickering Shadows series.

Steven DeLay's Finding meaning series

NEW: Joseph Mitterer's The Beyond of Philosophy serialised