47094: 16 What's Love When You Can Have Respect?

Every life is a strange exhibit. She buys a small plant on the way back. She spends a couple of hours doing emails and writing a blog. She phones x, y z and aspires to contain her internal self. There’s a substratum in the corridors and rooms. She’s always the kind who likes to perch somewhere in the distance. She likes to smoke because smoking gives her the picture of her ability to absorb her own flight.

And now she was at the market. If people are rarely insane, large crowds invariably are. She felt some weight which wasn’t easily discharged, as if what she saw in each face was someone looking for a break. Everyone was trying. Everyone was in trouble, having it hard, downcast, tired, down on their luck, out of synch, miserable, frightened, unlucky, needing a break. She seized that kind of feeling without putting it in her pocket. When had they each made their mistakes? Which day? Past and dead. You could forgive them all. But they would need to forgive themselves also. Yet too many of them had made a pact with their misery. That was the fatal flaw. And bowed to convictions as if eternity counted on it. That was the awful misfortune of them all. There was nothing but goodwill she could confer on any of them. She asked for nothing from them of course, save that if they interrupted her solitude they offered a welcome companionship. Nothing less. Nothing more. She always guarded against insinuations.

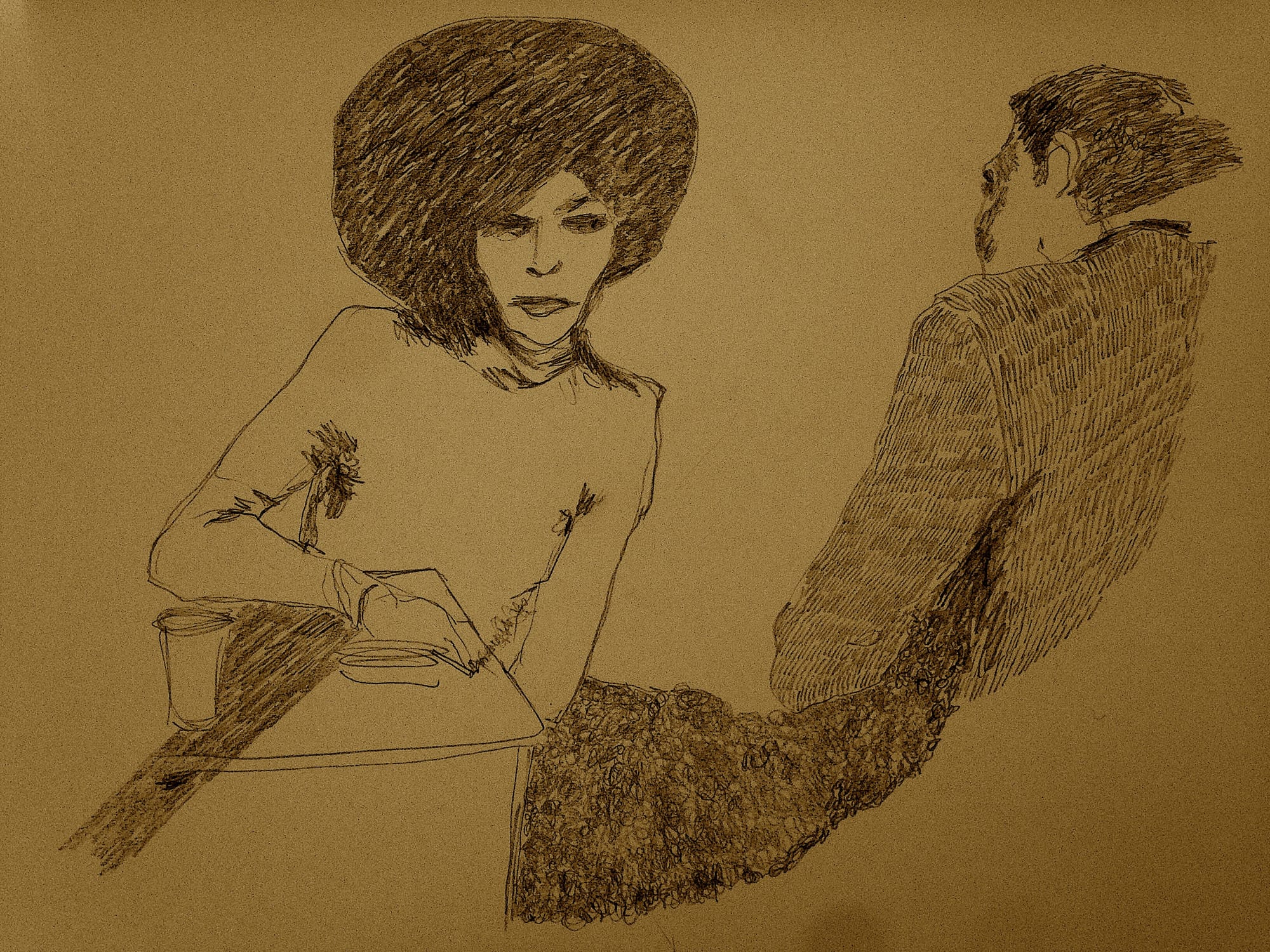

She wallowed there alone where the din of the crowds was the speech of violence and attack tamed by unexpected bouts of longing. She found city life a hammer against a lock. Her drab interiors were covered in impassioned expressiveness. She was a cross between polecat and Russian saint. Over a pint of beer she leaned as if an accordions’ last keening note. What did she like when she got intruded? Beauty that’s what. The damnest thing, in the middle of the night, when there was just a thin skin of intelligence hanging like a cotton thread from the ceiling and the ignorant dark, she felt she could give everything to the loveliness of her life, even in its hidden-away quality and mellow sentence. She could cling to thoughts like that, unexpected and free of illusion because they were unpositioned and not hinged by significance or anything needing accomplices. It was a way she had of finding her life being lived at a higher pitch than she had ever expected. Better, it was a way that left her amazed at the endlessness of souls, of the distraction that being alive gave her amidst what seemed just like disarray and stormy chaos at times, and frustrating because so disorderly and outside the reach of prayer.

What happens in the night when there’s no one else around?There's a climbing melodious reaction to what sometimes might feel oppressive and too still but wasn’t always, not even most of the time, but was rather a great sense of the infallibility of the heart when its moved to something ghostly and joyous, like that insane crazyness that is one long breathing catch over whipped up seas. Who is it running with the dogs? The bone catcher. What sort of beauty is it hammering across the door and the bed which isn’t actually visible except for a post and a fall of one rough blanket? It’s going to be a beauty that chides and amuses and delights and tears away its petals and makes you spin and weep and smile and run about, gripping ideas more than nature and then turning upside down so the faces are all nothing between birth and death but great wallops of humour and strange delights. And there’s nothing phony in the good nor in those who make it their time to try for it, to see what good might look like under the extreme pressure of what seems like, even in the daylight when it all really does look like this, like a world gone bonkers. Well well.

At night once she heard a gull cry through the hour, just a single yelp, and she lay still with her head only half out from under her pillow – that’s the way she was with pillows and the complex balance between sleep and wakefulness, she’d not swear to it, but then, it seemed as if, suffering her joys in silence, she had turned softly and held herself tight and waited for the startled sound of the midnightish gull to come again, in all the mixture of night and sea and bird and sky and what else? – the thorns of some grave pain or gratification in spades, a lasting good, a fight for the life almighty, well she was bold and that night was a sort of sublime forthrightness in its quiet, gentle type. She had fought hard but fell asleep again with the thought of a thousand other things that might have been worth staying awake for, because after all, a strange bird in the night is not the only thing, what with all our obligations to the ultimate confrontation with, I suppose, death and coping with being less than just strong enough.

What could she recover with her way of resourcefulness which seemed limitless, her way of seeing between points of infinities? She kept her good intentions to a minimum. She understood how weakness can flow from doing too much or wanting too little or just deciding. There were decisions, surely, but they needn’t be everything and certainly not decisive. As always whatever obligations she found she turned them over at a distance as if she wasn’t that keen to say it was finished and obvious and that therefore she was committed, committed to whatever it held. Happy things are forgiven things. Always taking things off the hook added a layer of complexity to even the most simple way and she admitted this, if to no one else but herself she did admit it, that time couldn’t be wasted on trivia or the storage in other people that bogged them down. Whenever they told her they were heartbroken or had some other ailment well she would think they should be so lucky, that life was always something you could recover from. And that only the dead can’t be grateful, unless, she wondered about this but then admitted that this is what she did indeed agree , you're crushed down too far.

And that was where she saw the days as expanding to – her days if no one else’s. She had an inkling even before, even when she didn’t exactly know things, but she felt that from what she had seen about people and the savage way of the centuries, she had an inkling that this was something that would be the case, of mankind under the massive tutelage of its burdens would have those who had fallen and were pushed to it, down, below the surface so that breathing was beyond belief and more a last instinctual bawl against the defeat. That’s what she felt about things. There were the crushed who had nothing to be grateful for. They were tortured by life and that was a way she’d be herself all twisted and tortured, tortured herself, but not in the same way, not in the unrelieved way that torture, real torture was. But she could still use it, so to speak , use the word but by doing so would know something more, something about the barbarism and savagery in all the great cities and the wide plains.

It stunned her when such thoughts multiplied her powers of living and crying and laughter. She held love at a slant. It ran oddly across her nose and cheeks some days so that her character and fate seemed to rise up and meet it halfway, wherever that was, because she felt all in all her nature was a little disguised despite everything nevertheless. She would eat with the calm appreciation of the magician for straightforward identities. She enjoyed what was given outside of imagination, in fact, she didn’t really know if she had imagination of the kind that people talked about as if some great force of nature or God, no. Food she did believe in, it sustains, alters, redeems her she laughingly reflected, and if history is cruel it’s where there is a lack of food or where metaphysics tries to replace vegetables. The mass of the crushed lived in tiny vacuums that needed to be burst and then came the great job of teaching them back to life, of giving them back a power so they could feel gratitude again, could eat and at the feast appear slovenly and acoustical and alive enough to convert one thing into another and so prove something, an alchemical reaction in the deep recess of heart blooming again.

That’s what she might have put in a letter to her mother who seemed to be incapable of rising outside of herself to even make excuses. How many times had she wondered about writing the letter and realised that she hadn’t the right codes for doing it in a playable key. How much labour might that take? Well, she often thought about it with a sense of awful wonder and dread. Everything worth doing was, when she was in this mood, done from the inside. Where is everybody? Out there, crushing others. Or being crushed. It wouldn’t surprise her to find that one day she’d walk out and everyone would be gone. What kind of day would that make? Inside her skin and breast some abomination of life, light, a glissade and a vindication. That’s what kind of day it would be. Where she was rounded up a hundred percent and was still there. What’s love when you can have respect? It’s a less draining virtue. Less dangerous. Less vanity and more shielded from the blows that fly down and mix you up.

Read 47094 from the beginning here.

Read the complete novel 'The Ecstatic Silence' here.